Doing it Backwards: My Unexpected Goldberg Variations (Part I)

As I look back over the last ten years, and the peculiar journey with J.S. Bach that the time represents for me, it’s sometimes hard to believe that I’m here, now, playing the Goldberg Variations in their entirety, from memory, for sometimes sizeable audiences, well enough apparently to get enthusiastic approval from the classical section of the New York Times. I’m really a jazz pianist, after all, and the Goldbergs are, by I believe pretty much everyone’s account, hard. And the crazy thing is that I never set out to do this in the first place. How did I get here? The best answer I can give, to echo an experience many Bach interpreters have reported through the years, is that Bach taught me.

I grew up in Paris, France, in an American family, and started studying piano at the local conservatory when I was six. I was never asked what I wanted to play, as some of my friends in the US were—playing TV themes wasn’t on the radar. Mostly, I was made to play Bach, lots of it. At the same time, following the example of my grandfather, who was a jazz pianist on the West Coast, I started improvising, and that mode of music-making quickly took over my fledging artistic identity, even as I kept going through the classical repertoire with my teachers at the Conservatoire.

So I grew up with solid classical training paired with an all-out obsession with jazz and improvisation, which I mainly taught myself. In my early teens, I discovered the Goldberg Variations at a friend’s house in Paris, as recorded by Glenn Gould in 1981, and they took hold of me then like the most beautiful and tenacious earworm. Still, it was only in my early twenties, while studying jazz at the New England Conservatory, that I got a score, and even then, it took me a long time to look past the Aria. Slowly, out of what felt like simple curiosity, I started learning a Variation here and there, in breaks between practicing jazz scales. By the time I moved to New York, in ’06, I had learned the first five, at most. And yet, even as I put all my efforts into breaking into the New York jazz scene and developing a personal voice as an improviser, the Goldbergs stuck with me. I kept coming back to them, and found a classical teacher, Zitta Zohar, who convinced me they were somehow within reach.

The jazz pianist Fred Hersch, a long-time mentor of mine, recently reminded me that he had asked me, back then, why I was spending so much time learning the Variations, music that I would presumably never perform. Apparently I answered, “I don’t know—it just feels like something I have to do.” And so I soldiered on, slowly and not all that surely.

Meanwhile, my fledging jazz career was developing. I got a boost from the American Pianists Association’s Cole Porter Fellowship, a competition prize that included a fair amount of touring. And so it was that I found myself backstage at a small concert hall in Czech Republic in early ‘08, fifteen concerts into a twenty-day solo tour, nearing creative exhaustion. I had decided for some reason that the gigs should be freely improvised, and I was starting to run out of ideas. So I decided to use the Goldbergs as inspiration: I played the first four or five, and followed each one with long, freeform improvisations that used the spirit of the preceding variation as a jumping-off point. The audience’s reaction surprised me—I walked off stage feeling that something special had happened. So I tried it again the next night. Bach’s genius suddenly struck me, hard: instead of panning for gold dust in a cold and barren stream, which is how it increasingly felt to make improvisations up out of nothing, using the Goldbergs as inspiration was like starting with a giant gold nugget in my hand. Each one had such an utterly distinct identity. Suddenly my improvisations, though still totally speculative and fanciful, had as their subject something very specific, something rock-solid and strong.

And so my improvising started to teach me about Bach. Back home, as I turned to him again with renewed enthusiasm, I wanted to know why it was that each of his short pieces felt so entirely of a piece. The answer—Bach’s extreme compositional economy—took a long time to reveal itself to me; strangely, it didn’t jump out at me at all when I was just learning to play the pieces. And yet, to take an early and simple example, Variation 2 introduces a motive in its first half that gets repeated nearly verbatim in every single bar of the second half, this motive itself being derived from the oscillating bass-line figure that repeats throughout. I can only describe Bach’s strategy for saving the piece from predictability as sleight-of-hand: like a skilled magician, he continuously directs our attention away from the obvious. The clockwork machinery hides in plain sight.

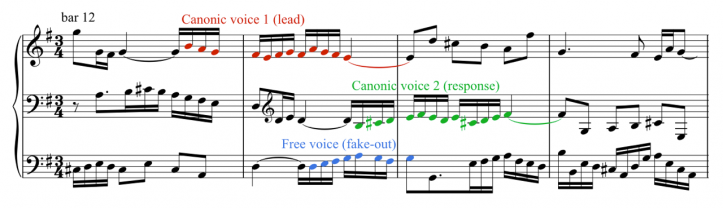

He uses misdirection throughout the Goldbergs, in fact. Where a lesser artist might have wanted to make his achievement in devising a series of canons at every interval from the unison to the ninth clear to the listener, Bach often seems to do everything in his power to hide it, even as he never breaks from strict canonical form. Besides the continuous overlapping and crossing of voices, which is its own form of disguise, there’s a wonderful moment in Variation 12 where the third voice - which is free and not subject to canonical rules - steals the thunder from one of the 2nd voice’s entrances by playing its melody a third away, a beat early.

Only the least pedantic composer would do such a thing. And this is in a canon at the inverted fourth, where a listener’s chances of anticipating the canonic response are even lower than in the non-inverted ones! An advanced volleyball-like fake-out is being deployed against an opponent who couldn’t possibly return the ball if he tried. Bach, I slowly realized, had his cake and ate it, too. His structures, if you look, are as plain as day and as solid as the steel skeleton of a modern building, and yet we rarely, if ever, notice them (as we often do, for example, in Handel). We only hear the incredibly expressive melodies, the rhythmic inventiveness, the continuous small surprises. Has a rule-follower ever been less boring than Bach?

By the summer of ’09, I had worked up enough courage to play eight of the Variations, followed by improvisations, at a small solo concert in Paris. I had been studying Zen philosophy and believed wholeheartedly that an improvisation should have integrity, as a piece of music, if I only put myself in an unobstructed frame of mind and let it flow, as it were, out of me. And the audience, for the most part, was convinced—it felt, again, like something special was happening, that I was exploring fertile ground.

But something started to gnaw at me: was it truly right, when Bach was being so phenomenally economical and elegant, to respond in such a freewheeling way? What would happen if I started to borrow some of his structure, too, beyond his emotional leads?

In the fall, I had a small solo tour through the Midwest, and played the Goldbergs on every gig. This strange idea I’d had—of following one of the most perfect works of art with quite imperfect improvisations—was starting to crystallize in my mind as something that had a certain legitimacy, partially as a result of personal conviction, but also because of the encouragement I was getting on the road. Still, a year went by before I started thinking seriously of recording it. In early ’11, after releasing a jazz piano trio album of original material and writing a concerto for piano and wind symphony, I happened to meet Bonnie Barrett, the director of Yamaha Artist Services in New York. I became a Yamaha artist and saw an opportunity: if I brought in my own recording gear, I could use the Yamaha showroom in Midtown Manhattan to make my solo record with virtually unlimited studio time. As much as I’d been performing the music in public, a part of me realized there was still a lot of work to do. I just didn’t know quite how much.

Editor's Note: Part II of this story can be read here.

Born in Paris to American parents, “tremendously gifted” (LA Times) pianist-composer Dan Tepfer has translated his bi-cultural identity into an exploration of music that ignores stylistic bounds. His 2011 Goldberg Variations / Variations, which pairs his performance of Bach’s work with improvised variations of his own, has received broad praise as a “riveting, inspired, fresh musical exploration” (New York Times). He has worked with the leading lights in jazz, including extensively with saxophone luminary Lee Konitz, while releasing seven albums as a leader. As a composer, he is a recipient of the Charles Ives Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters for works including Concerto for Piano and Winds, premiered in the Prague Castle with himself on piano, and Solo Blues for Violin and Piano, premiered at Carnegie Hall. Bringing together his undergraduate studies in astrophysics with his passion for music, he is currently working on integrating computer-driven algorithms into his improvisational approach. Awards include first prize and audience prize at the Montreux Jazz Festival Solo Piano Competition, first prize at the East Coast Jazz Festival Competition, and the Cole Porter Fellowship from the American Pianists Association. His recent soundtrack for the independent feature Movement and Location was voted Best Original Score at the 2014 Brooklyn Film Festival. Learn more at www.dantepfer.com.