Scratching the Surface: The Art(s) of Book and Music Making

Each month, Ethnomusicology Review partners with our friends at Echo: A Music-Centered Journal to bring you “Crossing Borders,” a series dedicated to featuring trans-disciplinary work involving music. ER Associate Editor Leen Rhee welcomes submissions and feedback from scholars working on music from all disciplines.

The following is a tiny offering of the kind of rich, rewarding work that interdisciplinary thinking can bring to musicology. In following my interests in print culture and music, I am continually humbled by the knowledge of material culture studies, iconography, and intellectual history needed to analyze a single page of sound culture. The study of print and books requires the forging of connections between disciplines to learn about craftsmanship, visual culture, and the sensorial experience of reading. No new digital technologies to learn: just the old-fashioned technology of conversation and attention to all the senses that a deep engagement with a book deserves. More and more, I am finding that music making cannot be separated from its print manifestations.

In the spirit of interdisciplinarity, I’ll begin with a poem inspired by music and print.

How should I praise thee, Lord! how should my rymes

Gladly engrave thy love in steel,

If what my soul doth feel sometimes,

My soul might ever feel!

[…]

Yet take thy way; for sure thy way is best:

Stretch or contract me, thy poore debter:

This is but tuning of my breast,

To make the musick better.

“The Temper,” George Herbert (1633)

The importance of print cut deep into the production of material culture. We find its mark even in poetry about music. For instance, George Herbert’s poem “The Temper,” is about the musical tuning and temperament of heartstrings (to “make the musick better”). But the poem also imagines the heart as an annealed (tempered) metal plate that can be printed continuously. Though this poem has no actual music, it draws clear connections between music, words, print, and books.

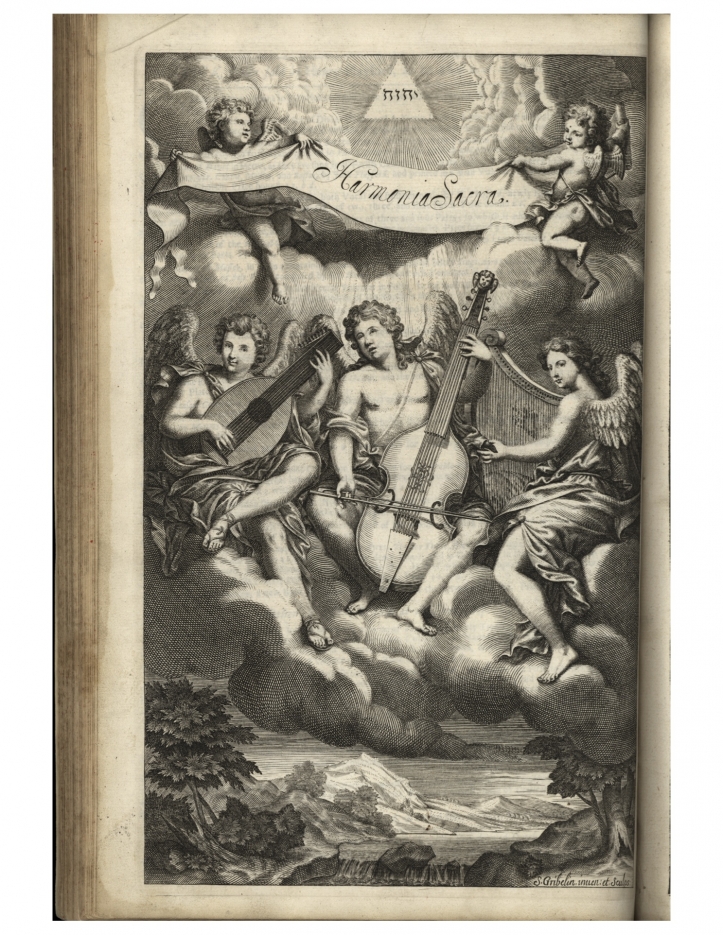

The first thing I notice when studying a book of song is that it is a material object, composed of many discrete parts, organized and compiled at different stages by several people. In other words, the book is an interdisciplinary project. A single page can reveal hours of careful planning and coordination of labor and skill. This is especially true of early modern print books of music, which often open with lavish frontispieces that visually announce the content of the book. More than just the music’s wrapping paper, frontispieces tell us a great deal about the concepts that governed the organization of the book. Take for instance the line engraving that opens Henry Playford’s Second Book of Sacred Hymns and Dialogues, Harmonia Sacra (London: 1693).

Though pretty, it is tempting to pass over this line engraving as an ornamented restatement of the title page. Stock angels playing music in a collection of sacred music: how obvious!

But this is a period in which emblems and visual art could express ideas better than words. More than just a “hook” to persuade me to press on, the engraving shows everything the book stood for, and, in this case, invites me to contemplate what sacred music is. If I can read the engraving, then I can understand how to approach making the music.

Line engraving was a serious investment of time and effort that was entirely separate from typecasting, which required another printing press. Simon Gribelin, a favorite engraver of Prince William III of Orange, Queen Mary, and Queen Anne, engraved this frontispiece. Line engraving is a specialized type of intaglio printmaking. Under a magnifying glass and with a variety of tools, the engraver cuts the print’s design into a metal plate (usually copper); these lines are then filled with ink. A piece of paper is laid on top of the metal plate and pressed down by a metal roller or a felt press to absorb the ink and emboss the paper—exactly the inverse of a relief print. Paper quality is an important factor to ensure proper absorbency and to preserve the detail of the engraving. Even with ideal paper, it can take a week for oil-based ink to dry from a line-engraved print. Done in many steps of proofing, reproofing, mirroring, correcting, ink-laying and wiping of each print, line-engraving was a laborious, detailed project deserving of its categorization as fine art. It behooves me then to examine it with care, since it appears before any music.

Upon closer inspection, the engraving tells me two important things about the book: the first is that it merges sacred worship with secular themes. The second is that it places the book in a broad history of Neo-Platonic ideas about music.

Merging Sacred Song with Erotica

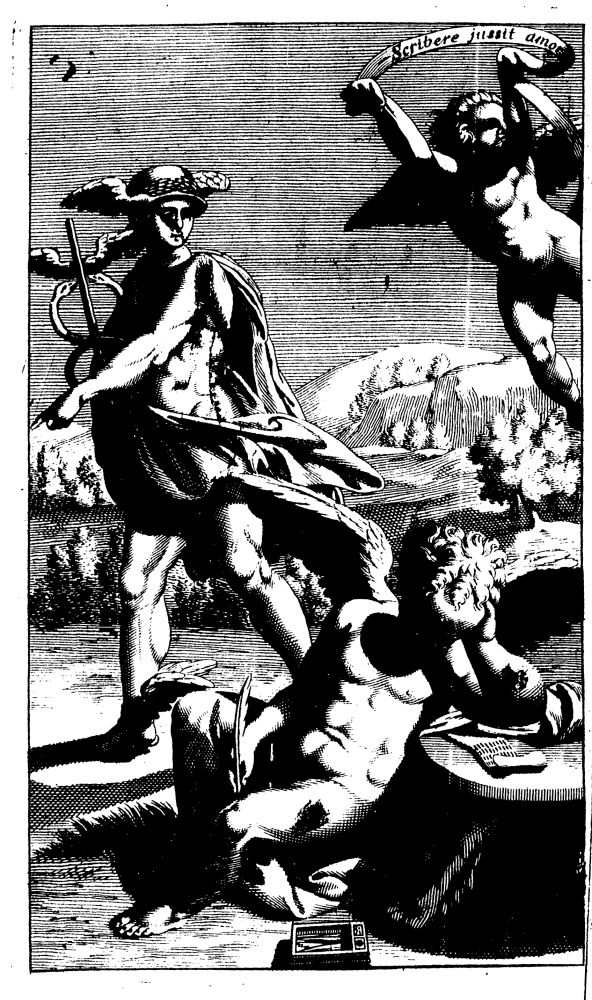

Above an empty landscape, three cherubs (or archangels) play their instruments on clouds. Higher still, two putti, or secular angels, brandish a banner bearing the anthology’s title. Overseeing all this is the tetragrammaton: the unspoken name of God. The placement of secular putti next to sacred cherubs is significant. These putti are like other putti that populate secular visual art of the period festooning deities with garlands of flowers or banners of fabric. The connection to profane love becomes obvious placed near secular representations of putti waving banners, such as the frontispiece to the Englishing of Ovid’s love letters, the Heroides (London: 1680), or the mid-seventeenth century “Triumph of Galatea” from the circle of Jacques Stella.

Against these and other images of embodied and frustrated love, Gribelin’s putti suggest secular themes of sensuality and desire. This opens an avenue to discuss sexuality as an integral component of early modern devotion. Indeed, as the songs show in their representations of madness, their fetishism of bodily fluids, and even, at times, indulgence in incestuous desire, the pious songbook also promises sexual and exploitative intrigue. But why stop there?

Neo-Platonic Ideas About Music

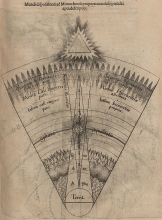

While the frontispiece can be read allegorically, it can also reveal an entire mentality of Neo-Platonic idealism about music. Specifically, it resembles Robert Fludd’s pyramids from his History of the Macrocosm and Microcosm (1617, 1623).

With the dazzling pyramid at the top of the image symbolizing the evaporation of material matter and the heavy pyramid weighed down with earthly elements, Gribelin similarly composes his engraving with the heavy material world at the bottom (landscape), followed by celestial music, and finally the realm of wordless immateriality. At the center of Neo-Platonism, Fludd’s treatises were full of emblems that superseded his prosaic philosophy. Important, too, is that his pyramid is directly related to his cosmic monochords, an obsession of his much discussed in the historiography of hermetic philosophy.

As shown in these prints, music elevated you to spiritual transcendence. It is striking, then, that the musical angels on the frontispiece play three kinds of string instruments to bridge the gap between heaven and earth.

In sum, the frontispiece tells us a great deal about what I’m getting into with this songbook: a book of music for worship, it is also a piece of entertainment as well as a complex philosophical statement. This is all before we even get to the music, yet it is entirely relevant to the study of the songbook.

We can still do something with the worn knowledge of other disciplines. If we forget, in our fever for new computational methods, that the music is situated in a material object, if we skip over the frontispiece and the history of its production looking only at the notated music in isolation, we miss the care and creative energy that generated the book itself. Moreover, we risk closing ourselves off to sounds emanating from poetry, images, and the books that contain them. And though I’ve been somewhat detailed about the frontispiece, there are pages of song just beyond it. That is to say, I haven’t even scratched the surface.