Stuff Smith & Robert Crum: Two Souls Touch

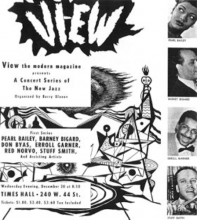

On Wednesday evening, 20 December 1944, a concert was held at Times Hall in New York. Touted as a presentation of “The New Jazz,” the concert was arranged by View: the Modern Magazine, a quarterly periodical specializing in modern art, film and literature.1 The concert line-up, which headlined Pearl Bailey, Barney Bigard, Erroll Garner and Stuff Smith, was organized by Barry Ulanov, a contributor to View and editor of Metronome magazine. The impressive list of concert patrons and sponsors boasted many prominent artists and philanthropists, including millionaires Mary Cushing and Helena Rubenstein, choreographer George de Cuevas, sculptor Alexander Calder, composer Aaron Copland, and artist Marcel Duchamp.2

To begin the second half of the concert, Smith was joined for two pieces by a young pianist named Robert Crum. The two had been rehearsing a type of improvised music which had little in common with the small group jazz of the day and which in fact anticipated the trans-idiomatic and cross-cultural themes that would become prevalent in improvised music later in the century. This was emphasized by Ulanov, author of the concert’s program notes:

“Should [these] improvisations be confined to jazz? In a series of deliberations, first canonic, then less rigorously formal, the violinist with the jazz background, the pianist with a classical, offer a provocative answer, as they extend the resources of the improviser to those of all music.”3

Despite providing a platform for newcomers like Garner and Bailey, as well as seasoned performers like Bigard and Smith, all of whom would go on to have long and successful careers, Crum, and the Times Hall concert itself, is barely remembered today. View’s “New Jazz” was overshadowed by the emergence of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie as the dominant voices of jazz in the mid-1940’s and beyond, but the Smith and Crum collaboration is relevant as a precursor to modern day free improvisation and the themes of cross-culturalism that attend it.4

Robert S. Crum was born in Pittsburgh on November 29th, 1915.5 A prodigious young pianist, he studied at the Pittsburgh Musical Institute from the age of 9 to 12 and at the Paris Conservatory when he was 14.6 When he was 16 Crum moved to Hollywood to write music for films, and he stayed there for three years.7 No film credits have been located, but he claimed to have written the main theme for the 1936 film Garden of Allah, for which Max Steiner was ultimately credited.8

In 1936 Crum moved to New York and befriended pianist Bill Clifton, who introduced him to jazz. Crum soon became an admirer of Art Tatum and Meade Lux Lewis, hearing them at Lower Cafe Society. He took a few lessons with Lewis at the club after-hours and would work out some of Tatum’s ideas at home after seeing him perform.9

After the death of his father around 1939, Crum spent two years in Erie, PA with his mother. Under the influence of Tatum, Lewis and Clifton, Crum’s style was transformed into a classical-jazz hybrid, as he worked for two years in small clubs. Around this time, Crum’s only known published composition was printed, entitled “I’d Rather Dream.”10 He moved to Chicago in August 1942 and by the following summer he was earning a living playing at the Hotel Sherman’s Panther Room. Crum’s elaborate and challenging interpretations of classical and popular melodies prompted a reviewer for Variety to write: “Mixing classics with pops … plays Masenet’s [sic] ‘Elegie’ in concert form: does an improvisation of ‘Can This Be Wrong’, following it with a boogie-woogie, and closes it with a syncopated version of ‘Humoresque’ that literally brought down the house.”11

Will Davidson explains Crum’s idiosyncratic approach to the Romantic repertoire:

“[The] search for meaning [of a phrase or score] is the strong foundation upon which Robert’s musicianship is built. He seems firm in a belief that the master composers must be thoroly [sic] studied and understood, because their contribution lies in the accuracy, the beauty, and the universality of their interpretation of life.”

Davidson crucially adds that

“The score is merely a guide, a mechanical preservative of that interpretation, and not always a satisfactory one, because there is no known symbol for an emotion. It becomes the challenge of the artist, then, to follow the guideposts of the score until they lead him to a contemporary interpretation of what the composer felt.”12

The word “improvisation” is used by critics throughout this period to describe Crum’s style. In early 1944, Davidson wrote that “[Crum] continues to create today’s most amazing improvisations.”13 A Billboard review in 1945 wrote that Crum’s “symphonic jazz interpretations … [begin with] half a chorus straight, and then [go] into a wild malange [sic] of introductions and arpeggios …”14 In 1946 the St. Louis Post-Dispatch advertised Crum’s performance of “symphonic improvisations.”15

Crum had also explored improvisation in a freer sense, without immediate reference to a particular song. Harmonica player Pete Pedersen remembers Crum as “a player in the Art Tatum style” and reminisced about the house parties for which he and Crum provided musical entertainment: “We’d say 'Give us a story' and we'd make a song to it … I’d start playing, and then Robert played something to go with what I just did. Then I’d play something that was in conjunction with what he played, and thus was the song made.”16

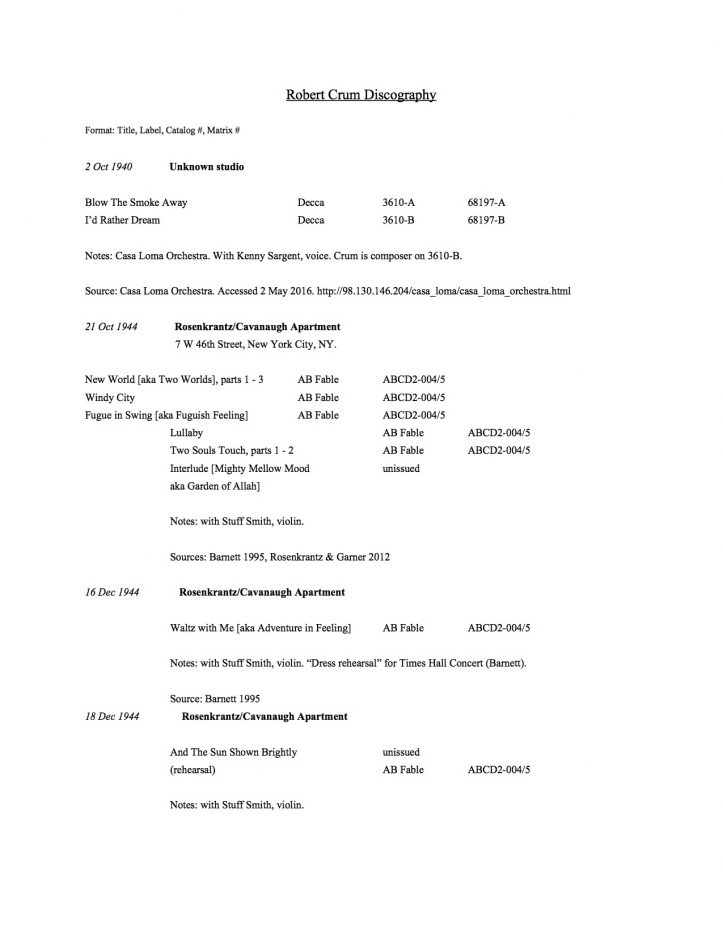

These improvisations are a prelude to the collaborations with Stuff Smith. Crum and Smith first played together at the Hamilton Hotel jam sessions during the summer of 1943. Crum had moved to New York by April 1944 to play at the Blue Angel nightclub.17 That October, he and Smith played together at the apartment of Timme Rosenkrantz.18 During these visits, Crum improvised with Smith in a freely associative manner. Recordings from all three sessions are held by the University Library of Southern Denmark, and Anthony Barnett has issued most of the October 21st session on his AB Fable label.

These collaborations culminated with the concert at Times Hall, an affair which received mixed reviews. Barry Ulanov wrote a glowing review of the concert in the March 1945 issue of View,19 while most critics expressed skepticism, especially toward Crum. Leonard Feather wrote that although “Stuff was superb, unpredictable, intensely rhythmic as ever … Crum, a frustrated classical pianist, seemed out of place.”20 Downbeat writer Frank Stacy called the improvisations “plain disconcerting,” citing Crum's “disturbing nervous [on stage] mannerisms.” The Modern Music quarterly published a largely negative review, but noted that “The bright spot in the [Smith & Crum] improvisation was a bitonal clash of personalities … Neither would yield, and so the piece ended in a most peculiar way.”21

After the Times Hall concert, Crum returned to Chicago, playing at hotels and nightclubs around the midwest. In mid-September 1946 he recorded six duets with the accomplished drummer Barrett Deems which were released by the Chicago label Gold Seal. In November 1947, Crum was “in a hospital for observation,”22 and in December 1949 he is mentioned briefly by a Tribune writer who laments that “Crum, once the poor man’s Paderewski, [is] wasting all that talent on the wrong side of Howard St.”23 Crum seems to have made no further attempts at a public music career, living a private life and passing away in Joliet, IL on 21 May 1981. His obituary does not mention any musical accomplishments.24

During his relatively brief career as a pianist, Crum had a minute but not negligible influence. Dr. Billy Taylor was sympathetic to Crum’s music and placed him alongside his contemporaries Erroll Garner, Bud Powell, and Al Haig as a notable pianist from the “Prebop and Bebop” style.25 Rosenkrantz once witnessed Garner take Crum’s hands as he told him, “You know ... I never knew what I wanted to do until I heard you play.”26 Though his contributions proved to be peripheral in their day, they constitute a genuine contribution to contemporary improvised music, in particular his collaborations with Smith.

Notes:

[1] “View: the Modern Magazine” published between 1940 and 1947. It was managed by Charles Henri Ford (editor) and Parker Tyler (assoc. editor). Each issue featured a contemporary artist, like Georgia O'Keeffe, Marcel Duchamp, and Rene Magritte.

[2] Ford, Charles Henri. “View – Series IV 1944”. Klaus Reprint: New York. 1969. p. 107. Print.

[3] Barnett, Anthony. Desert Sands: the recordings and performances of Stuff Smith: an annotated discography and biographical source book. Lewes, East Sussex, England: Allardyce, Barnett, 1995. pp. 125-126.

[4] See, for example, the International Society for Improvised Music’s statement that “today’s musical world is increasingly characterized by creative expressions that transcend conventional style categories.” Improvisation is, among other things, “spontaneous interaction between musicians from the most disparate backgrounds[.]” Available online at http://www.improvisedmusic.org/overview.html. Accessed 4 July 2016.

[5] Ancestry.com. U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2011.

[6] Crum and his mother traveled to France in January 1930 (“Will Study In Paris”, Pittsburgh Press [Pittsburgh] 31 Dec 1929: 8. Newspapers.com. Web. Accessed 30 June 2016.) and returned in March of that year (Ancestry.com. List of United States Citizen: S.S. Minnetonka sailing from Boulogne Mar 15th, 1930, Arriving at Port of New York March 24, 1930 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2011.)

[7] Pease, Sharon A. “Robert Crum Set for Sherman”. Down Beat, 1 July 1943, vol. 10, no. 13, 18. Thanks to Lindsay Million at the Middle Tennessee State University Center for Popular Music for facilitating my access to these issues of Down Beat.

[8] Steiner questioned this claim in a note from his secretary to Down Beat Magazine: “Mr. Steiner would like to know just what part of the Garden of Allah score Mr. Crum thinks he wrote.” (Down Beat, 15 Sept 1943, vol. 10, no. 18, 5)

Matt Endahl is a pianist, composer, and educator based in Nashville, TN. He teaches at Belmont University, Middle Tennessee State University, and the Nashville Jazz Workshop.