43rd IASA Annual Conference

This week's guest columnist is the Ethnomusicology Archive's own Aaron Bittel. -- Maureen

I'm going to start my first contribution to From the Archives with a confession: of the various library, archives, or ethnomusicology conferences I could choose to attend in any given year, my favorite is the International Association for Sound and Audiovisual Archives (IASA)'s annual meeting. Although based in Europe, IASA's focus is... well, international. Meetings might be held anywhere there are AV archives – which is to say, just about anywhere – and in recent years Mexico City, Sydney, Athens, Philadelphia, Riga, Pretoria, Singapore, and Oman have all played host. While I can't make it to these far-flung destinations every year, this year's meeting in New Delhi was one I didn't want to miss, for a few reasons. Chief among those is the hosting institution: the Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology (see also here and on that social networking site you've probably never heard of), part of the American Institute for Indian Studies.

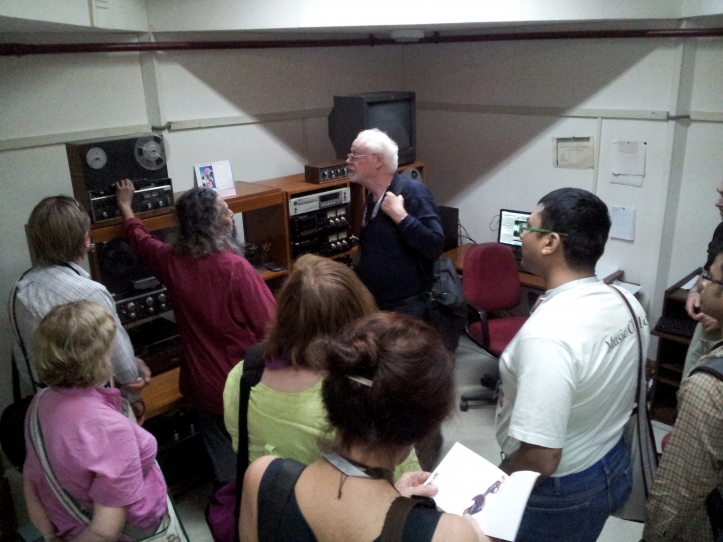

IASA tour of ARCE

The ARCE (pronounced as it's spelled out, in case you were wondering) is something of a sister archive to our own. Founded by ethnomusicologist Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy in 1982, who was also founding chair of UCLA's newly-independent Department of Ethnomusicology in 1989, the ARCE started its collections with field recordings from Jairazbhoy as well as his teacher, the Dutch ethnomusicologist Arnold Bake – recordings that are also in the UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive. Together these collections, along with recordings from Jairazbhoy's research partner and wife Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy, comprise eight decades' worth of audiovisual documents of music, dance, puppetry and related creative practices from all around South Asia.

It's not just history and collections we share with the ARCE. Besides the Jairazbhoys, UCLA Professor of Ethnomusicology Daniel Neuman and UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive Director (and Professor) Emeritus Anthony Seeger both have long been actively involved with the ARCE. And ARCE's director Shubha Chaudhuri, herself a well-known scholar and archivist, is co-editor of Archives for the Future, a book that plays a leading role in the course I co-teach at UCLA, Audiovisual Archives in the 21st Century. So it was a real treat for me to finally visit an archive with which I feel so many professional connections, despite it's being situated almost exactly halfway around the globe from UCLA.

Tony Seeger at ARCE

Of all of the activities that make up the practice we call “archiving” – and you'd be surprised just how many and how varied they are – one of the most important is repatriation, which I would roughly define in the archival context as providing access to cultural content for the communities that originated that content. In fact, ARCE was founded with repatriation in mind. And so it should come as no surprise that repatriation was a major focus of this year's IASA meeting, the theme of which was In Transition: Access for All.

As that title suggests, new methods and strategies for providing access permeated nearly every presentation. Other hot topics included media (in the broad sense as well as many specific senses), open technologies (including open source software), copyright, and ethics. The keynote address, given by Lawrence Liang of the Alternative Law Forum in Bangalore, was From Ownership to Trusteeship: Archival Challenges to the Imagination of Intellectual Property. Much of Liang's lecture focused on the nature and meaning, or meanings, of ownership asking, for example, what we mean when we say “this is my song” versus “this is my pen.” And yet this rather abstract and conceptual discussion held a sizable audience on the edge of its seat.

ARCE rooftop garden

Another reason IASA's annual meeting tops my list is that, by often taking them outside the more typical European and North American conference settings, IASA invites and attracts a significant share of the local cultural preservation community: archivists, scholars, musicians, technical experts, teachers, activists, and sometimes even policy makers and diplomats. Many are people who for various reasons might be unlikely to attend a conference in London or Chicago. It's possible some of them don't even think of themselves as archivists, or would think to attend an archives conference, except that it was in their home city or country. But they are creating, building, exploring, preserving, and opening up access to archives, taking approaches and going in directions that those of us whose business cards say “archivist” might never have envisaged from inside our institutions. Two brief examples: filmmaker and activist Surajit Sarkar whose Catapult Arts Caravan uses audiovisual media created by local artists to engage their rural communities in dialogue about the major issues faced by the communities, and musician and web designer Srijan Deshpande who sang the opening section of his paper on the intersection of musical performance practice and online music archives.

Qawwālī performance before final banquet

One of the things I enjoy most about IASA is that it is a relatively small conference where you can really get to know the major players in the global audiovisual archives community. And yet in this one meeting you have represented an incredible depth and diversity of knowledge, all dedicated to a common goal, which is nothing less ambitious than the preservation of the cultural memory of humanity. In five days, it does what a good conference should do: it leaves you feeling simultaneously energized and exhausted.