"Bâtards Sensibles" Insights into French Rap Production (excerpt from Bedroom Beats and B-Sides)

This text is an excerpt from Laurent Fintoni's book Bedroom Beats & B-Sides: Instrumental Hip-Hop and Electronic Music at the Turn of the Century

Author’s note: The following chapter is one of three focusing on what happened between the UK, France, and Canada during the first half of the 2000s. It’s preceded by a chapter about London, looking at Big Dada and the broken beat scene, and followed by a chapter on Montréal and indie hip hop in North America. The chapters in the book are formatted as beat tapes, with the intention to use the format as a way to move through narratives more freely and, hopefully, evoke something of the music in the writing. What this means in practical terms – especially if you’re reading this extract and nothing else – is that each sub-section of the chapter is titled after a beat/track/song prefaced by // and followed by the name of the producer. These titles act as both markers for shifts in the narrative and as a way to make your own soundtrack to the reading. Notes for attribution and citations can be found at the end under Sample Bank, any non-attributed quotes are taken from interviews I conducted.

Tape 13 - Bâtards Sensibles

In its early years, French hip hop followed closely in the footsteps of its American big brother. As we saw in Chapter 1, by the mid-1990s French rap beats were heavily indebted to the New York City boom bap sound, as were those of the country’s trip-hop aligned acts such as La Funk Mob and DJ Cam. The spread of the culture in France followed alongside a predictable path of celebrating, and practicing, its four core elements: DJing, MCing, breakdancing, and graffiti. The first hints at deviation from this arrived towards the end of the decade. Notable among them was the release in 1999 of Les Princes De La Ville (The Princes Of The City), the debut album by a new group called 113.

Hailing from Vitry-Sur-Seine, in the southern suburbs of Paris, the trio took their name from the building of the cité Camille Groult where they grew up. Like many of their peers, 113 fell into rap as an escape from the harsh reality of life as first generation immigrants – their families hailed from Algeria, Mali, and Guadeloupe. What ultimately set 113 apart from the national scene though was their choice to not walk the same well-trodden sonic paths as others. A choice that would lead them to success.

113 - Les Princes de la Ville (1999) (album cover)

// “Ouais Gros” [DJ Mehdi]

While ideology, location, and style were all important elements of French rap, the ghost of colonialism was also key to the music. The large majority of acts to emerge in the 1990s were the children of immigrants from the African continent and France’s island territories and they were unafraid to use the music to lay bare the failures of the country’s vaunted integration policies and rhetoric. Lyrically, 113 celebrated the joys, pains, and frustrations of life on the periphery. Musically, they leaned on a young DJ and producer, Mehdi Favéris-Essadi. The son of Tunisian immigrants, DJ Mehdi was from the northwestern suburbs of Paris and had been active in the local scene since the mid-1990s as part of the collective Mafia K’1 Fry. By the time he started working on the 113 album he had just hit his 20s and was growing increasingly dissatisfied with the rigidity of French rap’s sonic template. Unlike most, 113 were receptive to his unusual ideas and desire to try something different. The result was an audio tapestry that stood in stark contrast to the claustrophobic street aesthetic most were accustomed to.

Responsible for 10 of Les Princes De La Ville’s 13 songs, Mehdi weaved references to various eras and cornerstones of hip hop’s history in his productions, flipping previously used samples with a new twist while also switching tempos and digging deep into crates that most producers of the time left untouched. Key to his and the group’s approach was keeping the balance between old and new just right – for every left turn there was a somewhat recognizable line ahead. While the quality is high throughout the album, there are two memorable contributions: “Tonton Du Bled”, part of a trilogy dedicated to each rapper’s origins, with its marriage of sped-up percussion and string samples from Algerian music[1] to bass stabs and breakbeats; and the trio of “Ouais Gros”, “Jackpotes 2000”, and the title track which revamped the electro and fast rap template of the 1980s (with BPMs in the 110-120 range) through inventive flips of Kraftwerk, American r&b duo René & Angela, and soul pioneer Curtis Mayfield. The resulting songs weren’t far removed from party classics or the short-lived hip-house moment and tapped into the French hip hop scene’s close, though largely unspoken links, with house music via the use of frequency filters to handle the layers of samples and voices.

Released in October 1999, Les Princes De La Ville was French rap’s first commercial and critical success of the new century. It sold over 350,000 copies and in March 2000 the group won two awards at the annual Victoires De La Musique ceremony – for best rap/reggae album and best newcomer. The album was Mehdi’s parting gift to his hip hop roots and soon after he left rap behind. In the early 2000s, he moved into the burgeoning electro house movement, which built on the success of the French Touch explosion that had carried the likes of Daft Punk and Cassius – the new alias of Mo’ Wax act La Funk Mob – to international acclaim in previous years.

“The music I was making without even thinking about it, the music I was naturally drawn to and making with my hands and my ears, wasn’t that much appealing to the rappers I was working with anymore,” Mehdi said. “At one point I was like, ‘How many James Brown or Parliament records can I sample again?’ Everybody’s doing the same thing, and we’re all going from like 92 to 98BPM. Five, six, seven years you do this, and at one point you’re like, ‘Hey, this guy from San Francisco, DJ Shadow, is doing something different and these guys from across my street, named Daft Punk, are doing something very, very different with the same tools.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, yeah, let me try, why not?’ And some of the people who I was working with were interested in it and we made great records. I mean good records if you may, and some of the people I was working were like, ‘No, no, no, I want the old stuff, I want to keep on doing the same thing.’”

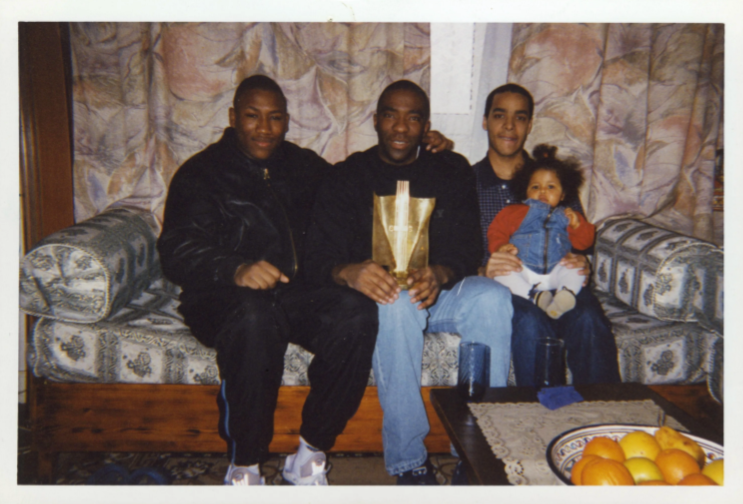

Mokobé, Manu Key, and DJ Medhi with the award from Les Victoires de la Musique (2000)

Photo: Thibaut de Longeville

// Game Over 99 [Mr. Flash]

For Julien Pradeyrol, rap was an unmissable cultural phenomenon which he found himself attracted to via TV, the only medium available in his house, and access to American imports through friends at his bilingual school in Paris’ 15th Arrondissement. Attraction led to mimicry and eventually to a sense that rap could be a serious outlet after a school friend introduced him to Dominique Bolore, an immigrant from Guyana who lived on the other side of town. The two teenagers practised together, made some demos, and in 1997 they were joined by Pradeyrol’s cousin, Alexandre Miranda, becoming TTC – the initials of their rapping alter egos: Tekilatex (Pradeyrol), Tido Berman (Bolore), Cuizinier (Miranda).

Trying to carve a lane for themselves in the competitive and crowded landscape of the Parisian rap scene, TTC decided to embrace hip hop’s engine of self-expression. They were no longer content with simply imitating the music they liked, nor were they willing to pretend to be something they weren’t. “You had to stand out because there were 15,000 other people doing the same thing,” Pradeyrol said. “Our way to do this was to put on some different voices, to rap on subjects that were a little bizarre. We couldn’t legitimately talk about the cités or what we didn’t know. We just wanted to be ourselves and we took rap as a means of expression. That was our trip.”

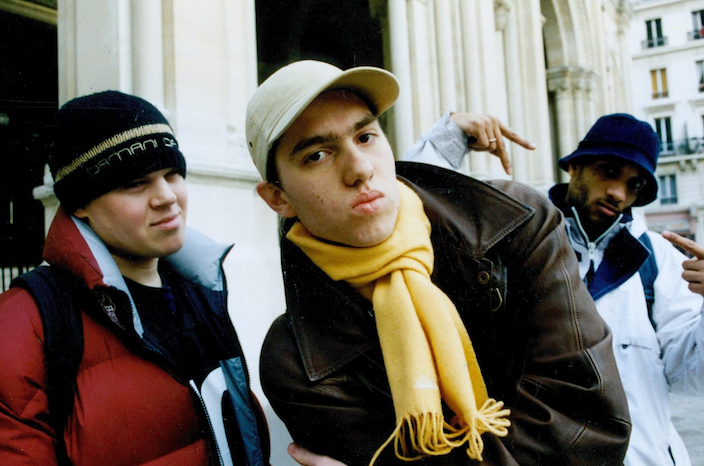

TTC

That trip led to two tracks, “Game Over 99” and “Trop Frais”, released as a 12" in 1999 and featuring video-game samples, odd rhythms, and unusual vocal stylings. The response though wasn’t quite what they hoped. People pushed back and questioned their aesthetic choices. According to Pradeyrol, “A lot of doors got shut in our faces.” At that point TTC were operating within a fringe element of the Parisian scene, loosely clustered around the DJ and producer Fabien “DJ Fab” Madeleine and a duo from Noisy Le Sec called La Caution. The same year TTC released their first record, La Caution dropped Un Jour Peut-Être (One Day Maybe), a mixtape showcasing this new generation of French rappers alongside a handful of their elders. The idea was to reflect the variety of rapping that existed in France, regardless of whether or not they, or the listener, liked everything. Another tape followed a year later, L’Antre De La Folie (In The Mouth Of Madness), this time orchestrated by Pradeyrol as TekiLatex and James Delleck, an up-and-coming producer and rapper affiliated with La Caution.

Driven by a desire to upend the constricting rules established by a previous generation, a small number of French acts – La Caution, TTC, Delleck, Cyanure, Svinkels, Fuzati, and producers including Fab, Orgasmic, Tacteel, and Para One – set about building their own scene. Over the following years, they performed together and put out a string of releases, in various combinations and formations, that captured a French hip hop sound in motion, playfully engaging with the same spirit of experimentation that was animating similar scenes around the world and which often fell under the moniker of alternative.

Pradeyrol was among the most active within this loose coalition, also working as a journalist for leading French hip hop publication Radikal, doing early internet TV, and tapping into the growing usefulness of the nascent rap internet to learn about and connect with others at home and abroad. For him, there was a sense that perhaps these French kids could build their own version of the independent, collaborative rap scenes that existed stateside, such as the one that was forming around Definitive Jux in New York City in the aftermath of Company Flow’s exit from Rawkus or around the Anticon collective (more on them in a bit).

Despite these efforts, within a few years the French alternative scene floundered under the weight of differing intentions and ad-hoc connections that didn’t reflect any meaningful cohesion. To describe any hip hop as alternative is always an odd proposition, as the music and culture offers anyone the tools to express themselves as they see fit. Today, we have rappers and artists whose differences are celebrated but back in the early 2000s alternative was a necessary byword for rap and beats that didn’t fit the stereotypes of the street or of aspiring consumption that industry and media had created around the music and which reflected the racial fears and prejudices of a white majority.

“Alternative rap? What does that mean?,” asked Olivier Cachin, a journalist who was among the first to treat hip hop seriously in France. “It means you’re not authentic because clearly that’s how they feel. There’s a real rap and there’s fake rap, and that is us? No. You can’t accept that tag.” Over the years alternative had been used to describe acts like De La Soul, The Pharcyde, or even Outkast whose approach didn’t easily fit into the dominant aesthetics of the music. As the 2000s began it also came to mean something else, as Cachin pointed out with regards to what happened in France: “Alternative rap was rap by white people, that’s what it meant.”

// Pas D’Armure (Para One)

TTC’s debut single was produced by DJ Fab and Gilles Bousquet, who went by Mr. Flash/Flash Gordon. Around the time of the release, Bousquet had set his sights on getting signed to a new London label he was a fan of: Big Dada. He got a hold of Will Ashon’s details and bugged him until the label head relented. While on a visit to London to see his girlfriend, he stopped by the label’s small office and played Ashon a bunch of beats, leaving behind a copy of the single. Despite lacking any meaningful grasp of the language, Ashon was mesmerised by the voices on the record. He told Bousquet that they weren’t interested in producers but would definitely be interested in the trio. TTC signed with Big Dada in 2000 and released their debut album two years later, Ceci N’Est Pas Un Disque (This Is Not A Record). Featuring absurdist raps that went down a rabbit hole from which there was no coming back, paired with a chaotic, hard-edged sonic tapestry inspired in no small part by El-P, the album was the logical culmination of the trio’s nerd-like dedication to the intricacies of hip hop and unabashed embrace of the alternative tag[2]. It was fun to a degree, but it was also a dead end.

While on tour for the album, TTC found themselves in Berlin. By then they were already developing a fascination with techno and, on a recommendation from their friend DJ Feadz, decided to stop by the Hard Wax record shop, the German capital’s vinyl temple to the music. Behind the counter was Gernot Bronsert, one half of German duo Modeselektor, rave veterans from East Berlin who were starting to make a name for themselves with their own alternative take on the Detroit sound. The rappers recognised Bronsert, who in turn knew who they were. As it turns out they were all fans of each other already and quickly struck up a friendship. TTC needed a way out of the creative cul-de-sac they’d put themselves in and soon realised that electronic dance music was the exit they were looking for.

Sample Bank

This chapter is titled after the 2004 TTC album released by Big Dada https://www.discogs.com/TTC-B%C3%A2tards-Sensibles/master/10293

“It sold over….” https://snepmusique.com/les-certifications/?interprete=113 for sales certification

“The music I was making…” A-Trak and DJ Mehdi 2007 RBMA lecture https://www.redbullmusicacademy.com/lectures/atrak-and-dj-mehdi-short-attention-span-people/

“You had to stand out…” Julien Pradeyrol 2018 interview with ABCDR Du Son https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rasvxqg0U2E

“A lot of doors…” ibid

All quotes from Olivier Cachin are taken from the 2015 documentary Un Jour Peut-Être: Une Autre Histoire Du Rap Français, which offers an excellent summary of the 2000s alternative French rap scene https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nos7FKoZw38

[1] The sample came from a 1960 ethnographic album capturing the voices and music of Algeria.

[2] Production on the record was handled by TTC’s growing circle of producers and a guest spot from London’s DJ Vadim, who was signed to Ninja Tune.

Laurent Fintoni has written about music and culture since the early 2000s. He began his career writing about the turntablist, hip hop and drum & bass scenes and throughout the 2010s was a regular contributor to FACT, The FADER, Bandcamp and the Red Bull Music Academy Daily among others. He has also worked as a tour manager, label manager and A&R for various independent labels and artists worldwide.

His first book, Bedroom Beats and B-Sides, is the result of more than ten years of research and work, beginning with a series of articles in 2008, a mix in 2009, and a series of talks in 2011. Born in France, he has lived in London, Tokyo, Brussels, Milan, and New York City and currently resides in Los Angeles where he is most likely driving around looking for food.