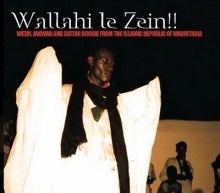

CD Review: Wallahi le Zein!

Wallahi le Zein! Wezin, Jakwar, and Guitar Boogie from the Islamic Republic of Mauritania.

Researched and compiled with written commentary by Matthew Lavoie, designed and edited by Dawson Prater. Latitude Disc/Locust Music 7, 2010. Two compact discs. Booklet (27 pp.) with notes, glossary, listening recommendations, color photographs.

---

Considering its position between the musically rich and well-documented culture areas of the Maghreb and West Africa, it is truly remarkable that little more than a dozen recordings of Mauritanian music have been commercially released outside the country.1 Of these, the majority have focused on Azawane, the highly structured music system of the Beydane iggawen (Moorish griots). Furthermore, these recordings have favored performances with voice and traditional iggawen instruments, including the tidinit (plucked lute played by men), ardin (harp played by women), and t'bel (kettle drum played by women), and in many cases go into great depth documenting the strict system of modes that defines Azawane. More recent recordings have begun to feature Azawane performances on electric tidinit and electric guitar as well, reflecting changes in Mauritanian music culture that have taken place since the nation's independence in 1960. However, while the impact of these changes on instrumentation have been documented in recordings made in studios or at concerts given in Europe, their impact on performance events within Mauritania have not been captured on recordings available abroad until now. Thus, the candid recordings of electric guitar music that Matthew Lavoie collected from Mauritanian cassette vendors and released on Wallahi le Zein!: Wezin, Jakwar, and Guitar Boogie from the Islamic Republic of Mauritania represent an important milestone in the documentation of Mauritanian music.

Whereas Azawane practices are believed to have remained relatively stable since at least the 18th century (Stone and Gold 1990; Bois 1997), rapid urbanization following independence has triggered significant changes in daily life for Mauritanians of all backgrounds.2 Although iggawen—who once served as praise singers for Beydane leaders—continue to dominate the role of musicians today, the traditional castes have begun to break down and non-iggawen may become professional musicians as well. Notably, the preferred term for performers is now vennane (artist), and although praise singing remains important, musicians make their livings performing for marriages, baptisms, birthdays, private concerts, and political rallies.

In these performance settings it has become desirable for musicians to play louder in order to attract larger audiences and therefore earn greater pay. This has led to two important changes. First, male musicians began to play electric tidinit, and eventually electric guitar. Secondly, as male musicians started to play louder, harder, and more frenetically, they began replacing female t'bel players with goorjiggen (gay men), who were socially permitted to play the "woman's instrument" and able to better endure the physical demands of a long performance. Michel Guignard criticizes the loud aesthetic of contemporary Mauritanian music, noting that it has led performances to be imbalanced shouting matches between musicians who, lacking monitors for their amplified instruments, cannot hear one another (2005:242-244). Furthermore, as Lavoie adds in Wallahi le Zein!, amplification systems and electrical cables are frequently in disrepair. Yet the interactive, dynamic energy of these performances is exhilarating, and for Lavoie, something that could not be captured in a studio, concert, or prearranged recording session, despite his attempts to do so. Thus, motivated to share those spontaneous moments that available recordings of Mauritanian music have failed to reproduce, Lavoie turned to the one source he could: cassettes recorded informally on low-quality recorders and boomboxes by the hosts of musical events. As demonstrated in the example below (CD 1, Track 4), the results are as rough as they are enthralling:

CD 1, Track 4. Mohammed Guitar, "Banjey"

The tracks on Wallahi le Zein! are organized in two sections. The first includes five tracks (CD 1, Tracks 1-5) that capture the guitar music of the Haratine, who are believed to be descendants of slaves from Sudanic Africa. Although they share a language and much of the culture of the Beydane, the Haratine did not traditionally have a griot class. Their music consisted of work songs, religious praise songs, and celebratory dances, and is not widely available on record (thus, it would have been beneficial to have included more Haratine music on this compilation). Today the electric guitar music of the Haratine is collectively referred to as "jakwar" by most Mauritanians, which, confusingly, refers to the name of a dance melody composed in 1976 by a Beydane tidinit performer; some Haratine musicians also call their music "banjey." The banjey included above (CD 1, Track 4) captures Haratine music at its most intense, with shouts from the audience, pounding t'bel, and frenzied guitar riffs.

The second and larger section, including the remainder of disc one and all of disc two, consists of Beydane music and is organized following the strict progression of the five modes that must be followed in any performance of Azawane. Most of these tracks are wezin, improvised instrumental melodies set to a lively rhythm that have been aptly referred to as "Saharan bebop" (Lelong 2006:24). The wezin by Jeich ould Chighaly included below (CD 2, Track 1) is an excellent example of the genre, and when compared with his tidinit wezin on the 1997 Aicha mint Chighaly album Azawan, l'art des griots (recorded in Paris), highlights how much musical energy is absent on other available Mauritanian recordings. Ateg ould Syed's "l'Ensijab" (CD 1, Track 9) also draws attention to the important dynamics between performers and audience: the common exclamation of enthusiasm from which this compilation derives its name, "Wallahi le Zein!" ("I swear to God, this is great!"), can be heard at 2:30.

CD 2, Track 1. Jeich ould Chighaly, "Wezin"

CD 1, Track 9. Ateg ould Syed, "l'Ensijab"

It is interesting to note how the guitar has become an indigenized instrument in Mauritania. Many musicians have resisted conventional playing techniques of the guitar, such as the use of chords. As mentioned above, the roots of contemporary guitar music are in the tidinit, and many of its performance techniques have been maintained on the guitar. In fact, traditional tidinit melodies called chewr continue to be played on guitar (see CD 1, Track 11 for an example), offering some respite from the intensity of wezin and banjey dance pieces. Musicians have made inventive modifications to the guitar in order to replicate the capabilities of the tidinit, in some cases adding frets (and in others, completely removing them) to enable the articulation of microtonal pitches belonging to the Azawane modes. Yet new features introduced by electric guitars have also been adopted. For example, one of the important innovators when it comes to modifying the guitar, Luleide ould Dendenni (heard below on "Hayak el Vennane," CD 2, Track 3), started a trend among Beydane guitarists when he carved a space in his instrument where he could attach a Boss Phase-shifter pedal. These various creative approaches have helped establish a truly unique sound for contemporary Mauritanian music.

CD 1, Track 11. Mohammed Cheick ould Syed, "Chewr"

CD 2, Track 3. Luleide ould Dendenni, "Hayak el Vennane"

With Wallahi le Zein! Matthew Lavoie has shed new light on a musical culture deserving of far more attention from ethnomusicologists. Vividly written notes document not only his experience of the music, but provide brief biographies of the featured artists and explanations of the selected tracks. Most lyrics are translated for listeners, but in some cases they are unfortunately incomplete. Additionally, considering Lavoie's enthusiasm for capturing the ebb and flow of the energy at musical gatherings, it would certainly have been worthwhile to have released longer recordings that may better represent the broader dynamics of a single musical event. I find it surprising that the album's opening track, for instance, fades out as a new piece is beginning to unfold. Nonetheless, Wallahi le Zein! makes a significant contribution to the body of Mauritanian music recordings available abroad and comes highly recommended for ethnomusicologists interested in the contemporary musical cultures of Africa.

---

References

Bois, Pierre. 1997. Liner notes. Mauritanie: Aïcha Mint Chighaly: Azawan, l'art des griots. INEDIT/Maison des Cultures du Monde W 260078.

Charry, Eric. 1998. "Review: Mauritanian Griote: Aicha Mint Chighaly." Yearbook for Traditional Music 30:182-183.

Guignard, Michel. 2005. Musique, Honneur et Plaisir au Sahara: Musique et musiciens dans la société maure. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, S.A.

Lavoie, Matthew. 2006. "Mauritania and Western Sahara: Ways of the Moors." In The Rough Guide to World Music Vol. 1: Africa and the Middle East (3rd ed.), edited by Simon Broughton, Mark Ellingham, and Jon Lusk, 240-247. New York: Rough Guides.

Lelong, Boris. 2006. Liner notes. Mauritanie: Guitare des Sables (Guitar of the Sands). Buda Musique 3017296.

Stone, Diana, and Nick Gold. 1990. Liner notes. Khalifa ould Eide and Dimi mint Abba: Moorish Music from Mauritania. World Circuit WCD 019.

---

Eric J. Schmidt is a graduate student in ethnomusicology at UCLA. Learn more about Eric at his website, http://www.ericjschmidt.com.

- 1. Both Lavoie (2006) and Eric Charry (1998) have previously noted this dearth of recordings. Fortunately, the Internet has facilitated distribution of recordings, and weblogs such as Voice of America's African Music Treasures Blog (of which Lavoie was formerly director; http://blogs.voanews.com/african-music-treasures/) and Sahel Sounds (http://sahelsounds.com/) are among those helping publicize contemporary Mauritanian music through streaming and downloadable audio files.

- 2. The figures are striking: Lavoie states that over 60% of Mauritanians were nomadic in 1960, yet by 2008 that number had dropped to 5%. In just over 50 years, the capital Nouakchott has seen its population balloon from approximately 5,000 to over one million.