The UCLA Hip Hop Initiative Hosts Chuck D as Inaugural Artist-in-Residence -- "Rap, Race, and Reality, with Public Enemy's Chuck D"

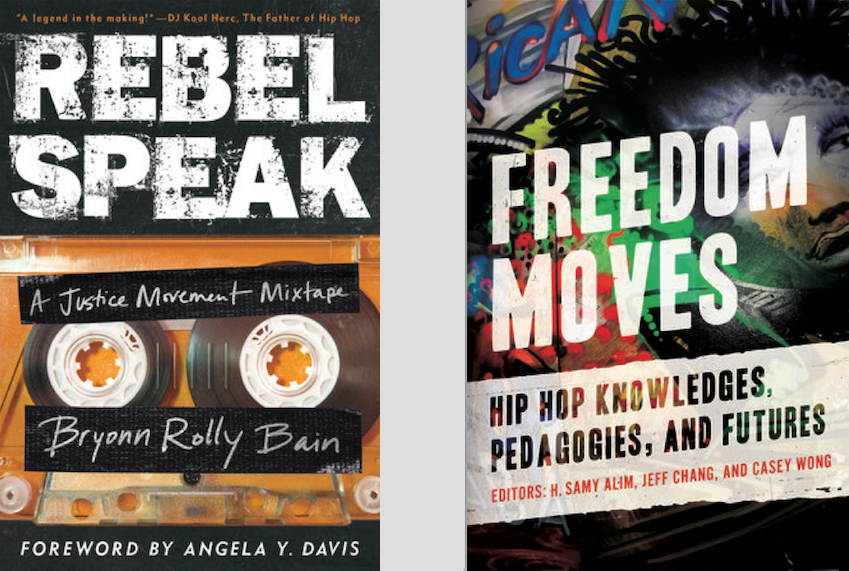

Wednesday March 30th, 2022 kicked off the UCLA Hip Hop Initiative’s (HHI) series, “Rap, Race, and Reality with Public Enemy’s Chuck D.” The series, will run the entire Spring Quarter and culminate with a public event at the California African American Museum on the evening of June 8th. In addition to Professor H. Samy Alim, Bunche Assistant Director Tabia Shawel, and Ethnomusicology doctoral student Samuel Lamontagne, Chuck D will be in conversation with many of the all-star Hip Hop Studies faculty at UCLA, including Professors Bryonn Bain, whose new book, Rebel Speak, on UC Press’s Hip Hop Studies Series drops this month, Adam Bradley, Scot Brown, Robin D.G. Kelley, and Cheryl L. Keyes, as well as world-renown Hip Hop journalists and thinkers, Jeff Chang and Davey D, authors of the new edition of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip Hop Generation and both members of HHI’s national advisory board, along with dream hampton, Joan Morgan, Ben Caldwell and others.

Session One: H. Samy Alim, Robin D.G. Kelley and Chuck D

Introduction to Hip Hop

The first session began with a brief introduction of the HHI by Tabia Shawel and Samuel Lamontagne, which highlighted HHI’s numerous projects and gave students an overview of the rich, decades-deep tradition of Hip Hop Studies here at UCLA. Immediately following, Professor H. Samy Alim delivered a critical 30 minute lecture focusing on “the activism and the aesthetics, the politics and the poetics” of Hip Hop (shout out to Tricia Rose and Imani Perry) in order to set the stage for a conversation between the great historian Robin D.G. Kelley and the one and only Chuck D of Public Enemy.

In Alim’s lecture, he began by noting that as we celebrate 50 years of Hip Hop cultural history, now is an opportune time to revisit our understandings of “this thing we call Hip Hop culture,” and start asking deceptively simple questions like, “What is Hip Hop Culture?” (the title of his lecture). In storytelling fashion, Alim bypassed common definitions of Hip Hop culture that simply run down “the 5 elements,” or “begin and end with post-industrial New York,” etc., and shared deeper meanings of Hip Hop culture from the cultural creators themselves, including Rakim, Lyla June, Talib Kweli, Mos Def (Yasiin Bey), A-lan Holt, Krip Hop’s Leroy F. Moore, Jr. (who was in attendance), and even Black Arts Movement poet Sonia Sanchez, noting that artists are themselves cultural theorists (shout out to the late great James G. Spady).

After covering various currents within the culture, including global, Indigenous, Black, feminist, queer, and dis/ability justice perspectives, Alim opened up the conversation between Kelley and Chuck D by offering a potential way to understand Hip Hop culture, drawn in part from his forthcoming book, Freedom Moves: Hip Hop Knowledges, Pedagogies, and Futures, with Jeff Chang and Casey Wong:

As we approach 50 years of Hip Hop cultural history, and 30 years of Hip Hop scholarship, Hip Hop continues to be one of the most profound and transformative artistic, literary, linguistic, cultural, and political movements of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Over the past half century, Hip Hop Culture has become a global ‘lingua franca’ (from the South Bronx to South Africa), an innovative, transformative arts movement rooted in Black expressive culture and Black freedom culture, that is constantly evolving in rich, creative ways that highlight style, pleasure, and joy, yes, but also a collective politics of healing and growth that helps oppressed communities imagine alternative futures, expand the project of justice for all, and ultimately, make freedom move(s).

Alim ended by complicating our understandings of Hip Hop citing Kelley’s own words: “But the fact remains that hip hop’s corporate face is one that promotes raw capitalist values, violence, and extreme materialism… [There is] no simple way to characterize what is at once a global social movement and a multibillion dollar industry. It ain’t final simply because it ain’t finished.”—Robin D.G. Kelley, 2006, The Vinyl Ain’t Final (p. xvi)

With the stage set, Chuck D and Kelley engaged in a wide-ranging conversation and dialogue with students that spanned over 2 hours. With decades of wisdom and insight, they shed light on the origins of Hip Hop culture as rooted deeply and undeniably within Black musical and oral traditions (with Chuck D noting that “Fight the Power” has roots in the Isley Brothers, as one example). They exploded traditional definitions of musical genres by arguing for an interconnectedness between Black musical, cultural, and linguistic production over the centuries, complicated by complex urban geographies, and the various Black flows of migration and immigration, and continuing to evolve in new directions. While Chuck D captivated the audience with personal narratives of growing up in Long Island, his earliest musical memories and memories of being an award-winning artist (not writing poetry until he was in college), he, along with Kelley, used those narratives as a spring board to discuss the critical social, economic, and political issues of the current moment.

Chuck D concluded by expressing his gratitude and encouraging students to dig deeper, to pay attention to all that is happening around them. “These are the kinds of conversations that I’m excited to have over the next ten weeks. I hope that these sessions change what you think about Hip Hop culture, and that we also change as we grow and learn together every week.” By all accounts the conversation was rich, inspiring, thought-provoking, and as Kelley and Chuck D noted themselves, “could have only happened at UCLA!”

Session Two: Jeff Chang and Chuck D

The Evolution of the Hip Hop Artist

On Wednesday, April 6th, 2022, the Hip Hop Initiative’s second installment of “Rap, Race, and Reality with Public Enemy’s Chuck D,” we witnessed the entrance of award-winning journalist, historian, DJ, musicologist, and UCLA Hip Hop Initiative national advisory board member, Jeff Chang. H. Samy Alim welcomed everyone by pointing out two historical moments: (1) The very room where we were gathered was the same, exact space where Jeff Chang delivered a keynote for the first Undergraduate Hip Hop Studies Conference at UCLA in 2005, and (2) The last time that he, Jeff Chang, and Chuck D were in the same space together was almost exactly 11 years ago on April 28th, 2011 on a panel for his Stanford University course, “Global Flows: The Globalization of Hip Hop, Art, Culture, and Politics,” which also included Gaye Theresa Johnson, Samir Meghelli, and Dawn-Elissa Fischer. Foregrounded by an awe-inspiring discussion the previous week between Robin D.G. Kelley and Chuck D, we were then led on a world tour that began with Hip Hop’s roots and ended with Hip Hop’s futures.

Chuck D began by emphasizing the importance of telling our stories—making sure that students come correct—recognizing how Jeff Chang wrote a book, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation, that is widely considered the best account of Hip Hop history ever written. Chuck D congratulated Chang on the release of the young adult edition with Dave “Davey D” Cook (who will be visiting the series on April 13th). Chang contextualized how the new edition brings Can’t Stop Won’t Stop to the historical present, focusing on speaking to the audience that defined the culture: young adults. While often overlooked, Chuck D revealed how Jeff Chang’s iconic first edition traced how Hip Hop emerged from the flight of African diasporic peoples escaping Jim Crow and colonialism in the Global South, to the streets of the Bronx.

Chuck D invited us on a journey. That journey historically and geographically began with the rhythms and creativity of enslaved peoples forcibly torn from West Africa, sharing moments of freedom across languages and cultures at Congo Square, and then pursuing liberation by means of the Blues, Jazz, Motown, and Soul, up the Mississippi River from Memphis, to St. Louis, to Chicago, to Detroit, and finally up to New York City. And addressing the curiosity of attendees about what the Caribbean had to do with it all, Chuck D and Jeff invited us to see how Black peoples, like Kool Herc, migrated from Jamaica and Puerto Rico making flights for freedom due to oppressive conditions. The multi-decade historical and geographical migration from White supremacy led the Bronx to assemble a historically unprecedented community of African peoples, knowledges, creativities, technologies, and ways of being, speaking, and valuing, which laid the foundation for Hip Hop becoming one of the most impactful artistic, cultural, and revolutionary movements in the world today.

Chuck D and Jeff Chang framed how Hip Hop is part of an ongoing legacy of Black media seeking to challenge misinformation (Don’t Believe the Hype!), and the dehumanization and flattening of the lives and stories of Black and oppressed peoples (i.e., why Chuck D has called Hip Hop “the Black CNN”), like Tupac Shakur, Luther Campbell, and even contemporary artists, like Travis Scott. Chuck D, and Chang kept it real, telling students that their struggle would be to take control of the “real estate of their minds,” and how Hip Hop could become a tool for liberating their communities and minds if they resisted its ongoing entanglements with racial capitalism. Following their explanations of how Hip Hop has always faced the contradiction of being a “commodity culture” and “community culture,” Alim, referencing conversations with dream hampton and the work of Tricia Rose, framed this historical tension as a situation where Hip Hop has simultaneously become the “cultural arm of capitalism” and the “cultural arm of [freedom] movements.” They ended with a challenge to those in attendance, calling them to take responsibility for being the “cultural GPS” for where Hip Hop can and could go. In the words of Chuck D, “young energy” would be needed to sustain, revitalize, and advance Hip Hop as a liberatory art and culture.

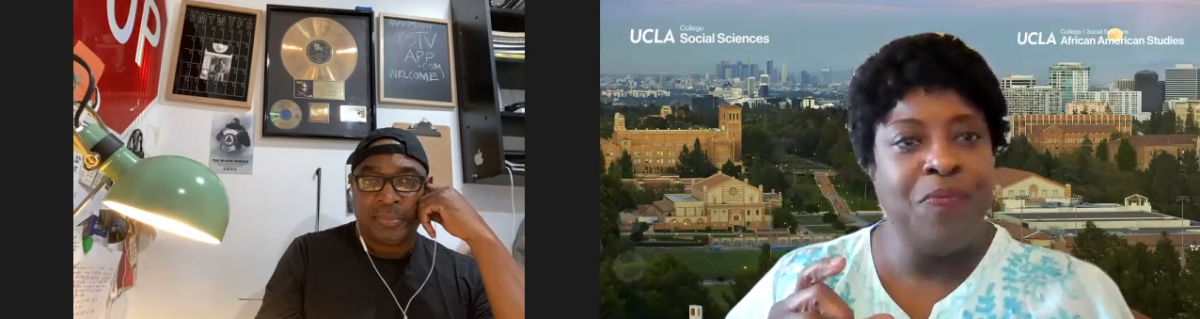

Session Three: Davey D and Chuck D

Hip Hop Culture and the Media & Music Industry

On April 13th, 2022, the Hip Hop Initiative’s third installment of “Rap, Race, and Reality, with Public Enemy’s Chuck D” featured guest Dave “Davey D” Cook, a nationally recognized journalist, adjunct professor, Hip Hop historian, syndicated talk show host, radio programmer, producer, deejay, media, and community activist. Davey D is also co-author with Jeff Chang of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, the Young Adult edition, which students are reading for the term, and a member of the HHI national advisory board. In his opening lecture, Chuck D recapped the previous sessions with authors Robin D. G. Kelley in week one and Jeff Chang in week two, and then touched on the technological innovations that largely define the “Golden Era” of hip hop from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s. He took us through a timeline of the music industry’s embrace of new media formats such as the long-playing vinyl, the 8-track cassette, the cassette tape, and, the compact disc, and how hip hop slowly transformed from a singles-driven business to album-length artistry.

Before bringing up our special guest, Chuck D shared how Davey D’s early promotional support as well as his passion for collecting cassette tapes were instrumental in his conceptualizing the Fear of a Black Planet “dissertation,” Public Enemy’s seminal 1989 album constructed from collaged sound bites and politically charged lyrics he wrote on Greyhound buses between tour stops. Lastly, Chuck D shared his deference to his heroes the Black Panthers and a story about seeing Huey P. Newton in the front row of a Public Enemy concert in Oakland’s Kaiser Convention Center—and then inviting him on stage! After Tabia Shawel’s formal introduction of Davey D, Professor Alim acknowledged the generosity, attention, and care present in hip hop community and how he survived his initial experiences as a Stanford graduate student, in part, by the real hip hop and community conversations that Davey D nurtured in the Bay Area on Street Knowledge.

Chuck D and Davey D have extensive history as friends, and it was apparent from “jump” that the conversation would continue in the already robust tradition set by inaugural guests. Davey D launched into powerful themes concerning the transference of generational knowledge, our responsibility to each other in the communities we build, and being on your “A” game at all times. He advocated that we all live by rap superstar and businessman Jay-Z’s mantra “I will not lose” and carry ourselves out of corporate consumerism that has made hip hop “a shell of itself.” (Of course one can hear echoes of Chuck’s voice, “refuse to lose!”, in the Public Enemy classic, “Welcome to the Terrordome.”) Additionally, Davey D and Chuck D agreed that “not being wack to your crew” (or holding up your end of the bargain and developing trust in community) is a mandate in hip hop and a word to the wise in all walks of life. As he shared stories of retaining rights to his intellectual property as a content provider, Davey D also stressed cooperative economics, telling our own stories, and being rightful owners of even our own thoughts. After sharing his excitement about where Hip Hop activism is today, and his optimism for what’s to come, he asked all of those present: “How are we engaging each other to take hip hop to the next level and what is the next level?”

Session Four: Scot Brown and Chuck D

Hip Hop and Funk

On Wednesday, April 20th, 2022, the Hip Hop Initiative’s fourth installment of “Rap, Race, and Reality with Public Enemy’s Chuck D,” we hosted UCLA Professor of African American Studies and History, Scot Brown, a member of the Hip Hop Initiative’s advisory board, in conversation with Chuck D on the relationship between “Hip Hop” and “Funk.” Dr. Brown is a leading scholar of African American history, popular culture, and music, and is the author of two books, Fighting for Us, and Discourse on Africana Studies. While many in attendance were familiar with Professor Brown because of his appearances on TV One for multiple episodes of Unsung – including Chuck D who praised Brown for his episodes on Funk music – his work has also appeared in numerous scholarly journals and edited volumes, on NPR, BET/Centric, PBS, Cinemax, and other venues. As a scholar-musician, Dr. Scot Brown a.k.a. Scotronixx has released music on all streaming platforms, including the recent song “Last Man [Remix],” featuring Mr. Ric, Rick Marcel and fellow UCLA Professor and HHI advisory board member Bryonn Bain. Many in attendance were hyped to witness two musicians and scholars lay it down and school us on Black music and historical relationships across genres.

Building on the previous weeks’ conversations with Robin D.G. Kelley, Jeff Chang, and Davey D, Chuck D – dressed in all black, all the way down to his black sneakers – began the session by shouting, “Welcome to the land of funk!”, as he introduced Dr. Scot Brown. Chuck D set the stage with a fascinating lecture about the various interpretations of “funk,” including how even certain expressive Black sounds, including the voice and nonverbal expressions, epitomized the spirit of funk, that it was something “hard to put your finger or nose on,” but yet widely understood within Black communities. Chuck D and Professor Brown engaged in a wide-ranging, informative, and at times hilarious conversation about everything from the role of the Isley Brothers, important sites of funk music like Ohio, Louis Armstrong’s musical interventions and “loud” voice as a precursor to other forms of Black music, the relationships between the piano, drums, bass and guitar in live music, and of course, funk legends and icons like James Brown, Sly and the Family Stone, and Bootsy Collins.

Turning to the social and political aspects of funk music, Chuck D reminded everyone that “funk” was seen as a bad word just like how “back in the 1960s, Black was a bad word. You better not call somebody Black!” – and then emphasized that Black people often take cultural control of these terms and make them beautiful and a source of community building. This is what happened during all of the many Black musical festivals around the country in the 1960s and 1970s, added Professor Brown. Chuck D highlighted these park gatherings as key, and connected them to Questlove’s Oscar-winning Summer of Soul, as one example of Black people coming together through music, including funk, in the most turbulent of times after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, multiple assassinations of Black leaders (Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Fred Hampton, Mark Clark and others), and Black soldiers fighting and dying in the Vietnam War. Following those observations, the conversation turned to the economics of funk and Black music with a discussion of the business acumen of artists like Prince, George Clinton, and right on through to the Wu-Tang Clan, as they not only called out the recording industry for their greed but also devised strategies to circumvent that. Regarding Prince, Chuck D broke it down by saying, “Prince’s beef was that the music business wasn’t moving fast enough for him. He broke their system,” and then argued that “Apple’s iTunes took down the music industry by being the first to have mass music online!”

Dr. Brown and Chuck D not only brought the funk, but they literally brought it with Dr. Brown providing a playlist that only a true funk scholar and lover could provide! Dr. Brown played and discussed excerpts from Sequence (“Funk You Up” and the role of Sylvia Robinson) and the Ohio Players (“Black Cat”), which was described as “the pre-rhyming that happened in funk music prior to rap music,” while Chuck pointed out that “Here Comes the Judge” (1968) by Pigmeat Markham was probably the first rap record ever! Dr. Brown ended the session by playing “Bring the Noise” by none of other than Public Enemy to demonstrate how Chuck D was a musical and lyrical innovator, not only sampling James Brown, but also kicking that triplet rhyme scheme that would later be commonly used by hip hop emcees. The session with Dr. Brown and Chuck D clearly showed the need for all of us to understand the historical underpinnings of and influences on hip hop culture and music as we move forward to next week’s session with Dr. Cheryl Keyes.

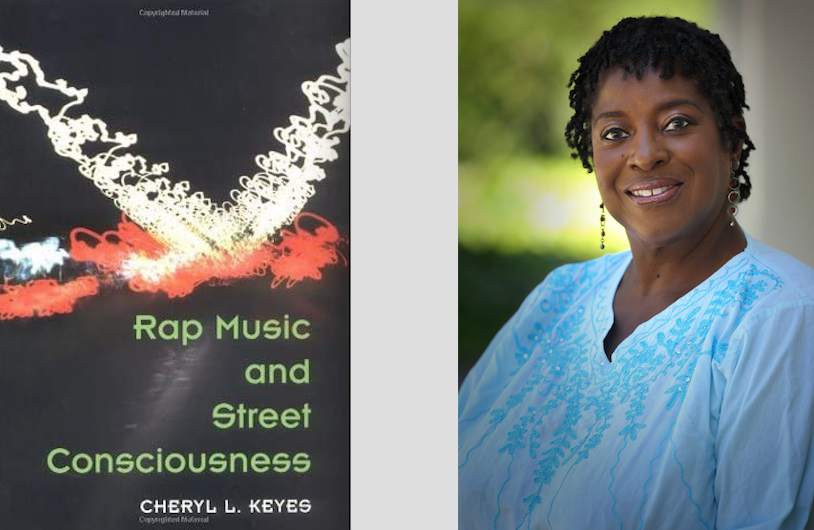

Session Five: Cheryl Keyes and Chuck

Women in Hip Hop

In week 5, the UCLA Hip Hop Initiative’s (HHI) series, “Rap, Race, and Reality with Public Enemy’s Chuck D,” turned to the crucial topic of women’s participation in the evolution of hip hop. Chuck D opened the session by focusing us on the problem of gender inequality, beginning with the question of why there are so few women in government and business, and then extending that concern with women’s representation to the male-dominated field of hip hop. Throughout the session, both he and the evening’s invited guest and HHI board member Dr. Cheryl L. Keyes, brought us to the clear understanding that the quality and impact of women’s contributions far outweigh their quantitative presence. In Chuck D’s words, “rap wouldn’t have the hop to it—or especially the hip to it—if women weren’t involved in its making, its manifesting.”

Questioning the propensity of taste makers to exclude women from judgments of who comprises the top 5 and top 10 rappers, Chuck D gave a strong big up to MC Lyte, describing her as an MC who can “spit and go,” coming harder than any dude—and with a “doper voice,” to boot. Pushing back even more, he pointed out that Sylvia Robinson of the 1950s duo, Mickey and Sylvia, not only was co-founder of the influential hip hop label, Sugar Hill Records, but she was also crucial in every step of the conception and production of “Rapper’s Delight,” the first rap music album released by a commercial label. In addition to what Chuck D describes as her “big bang theory” of forming the Sugar Hill Gang, he reminds us that Robinson wasted little time in heading down to South Carolina to form the first all-women’s group, the Sequence. In other words, women have, since the earliest days of hip hop, been crucial to the evolution of the art form and its outlook. Chuck D took this point even further by pointing out that to this day, Lady B (“To the Beat Ya’ll,” 1979) is not only one of the first female rap soloists, she is the longest running broadcaster of hip hop music. Thus, he proposed that to truly “set itself free,” global hip hop needs to embrace women’s presence and enter into an era of “exploration” of women’s excellence and turn away from the “exploitation.”

This exhortation to “explore” marked Chuck D’s introduction to the evening’s invited guest, Dr. Cheryl Keyes, Chair of African American Studies and professor of ethnomusicology and global jazz studies at UCLA, leading Hip Hop Studies scholar, and author of Rap Music and Street Consciousness as well as the monograph, “Rap/Hip-Hop,” in the Oxford Bibliographies in Music series. Dr. Keyes’s 1991 dissertation, “Rappin to the Beat: Rap Music as Street Culture among African Americans,” makes her a crucial pioneer in the study of hip hop and a key witness to the evolution of women’s unique stylistic approaches to the genre and to their strategies for carving out space in hip hop. As a young woman from Louisiana, she was not only intrigued by the novelty of the sounds coming out of New York in the late 1970s, she was also struck by how familiar it sounded. In the Sequence’s “Funk You Up,” she heard the influence of Black cheer, elsewhere, she heard Louisiana Bounce. Thus, she would bring her ear for Black music and her love of seemingly competing domains such as the church and the streets to construct important understandings of hip hop as a legitimate field of study. In the process, her ethnography and her promotion of hip hoppers as artists and philosophers in their own right, she herself would become an important component in hip hop history. As Dr. H. Samy Alim put it, “you betta believe” her work “broke down doors” that ultimately made projects such as the UCLA Hip Hop Initiative possible.

One of the crucial questions Chuck D posed to Dr. Keyes pertained to the role that men ought to play in the development of women artists and the messages they craft. In other words, he asked, how do men hip hoppers avoid “encroaching upon the personal opinion space” of women artists. He clarified that this question arises from that fact that he will be launching a radio app that plays only women hip hop artists as part of his broader goal of lifting up women artists. Everyone has art in them, Chuck D proposed, “getting it out of them is the goal of us curators and caretakers. Either you’re a caretaker or an undertaker.” Chuck D expressed his desire to take up a role of caretaker by making space for “exploring” women artists’ limits and boundaries without exploiting them. In this, Chuck D proposed that men’s domination of hip hop has constructed a metaphorical “house” in which women seem welcome and comfortable in no more than one or two rooms, ultimately leading to many women’s early exit from the house altogether. For Keyes, the most important role men hip hoppers can play is that of the mentor, ensuring that women who want to break into the field have the knowledge and skills necessary for a woman to “find her space, her unique voice” as an artist. Here, she paid respects to one of her own mentors, jazz trumpeter, Clark Terry, who formed an all-woman jazz group to promote the talents and capacities of women. The second most important role, she proposed, is to recognize when that mastery has been attained so you know when to step back and let her craft her own message.

Yet, Keyes does not deny that women often must make tough decisions about how to make a living off of their music. Complicating the duality that Chuck D proposed between exploration and exploitation, she proposed a third path, desperation: an overriding desire for such things as fame and money that pushes one towards exploitation with eyes wide open. In the Q & A, a student asked if women “reclaiming their sexuality and being open about it” is “enough” for women to push back against degrading and objectifying uses and depictions of their bodies and reclaim their sexualized bodies.” In response, Dr. Alim turned our attention to the works of Black feminist scholars of hip hop (e.g., Joan Morgan, Brittney Cooper, Treva Lindsey, Kaila Story, etc.) who have proposed ways of understanding how women are engaging these politics, yet he also reminded us that the challenge for women as they are reclaiming ownership of their bodies is that images of women, regardless of the intention that a woman may put into that image of herself, “circulate among folks who already possess these kinds of (derogatory) ideas about women.” “That,” he continues, “is the nature of being involved in this sexist beast.” Explicating and complicating this point even further, Alim contrasted the problematic of women taking ownership over the objectification of their bodies with Black men’s exploitation of images and stereotypes already in circulation. Ultimately, Alim argues, this process entails Black men turning exploited images of themselves into profits, thus “playing the capitalist game on capitalist terms.” For women, he argued, this situation is different in that Black women must contend with the triple threat of race-, gender-, and class-based understandings of who they are. Ultimately, he added, “what’s so frightening to men is that Black women are not only reclaiming their own bodies but they are producing images and narratives that decenter men, and emphasize that Black women’s pleasure is not dependent upon men—period.”

This question was, quite appropriately, followed by a question about the origins of Queen Latifah’s conception of herself as a “Queen.” This question sparked a rich discussion of the historical, philosophical, and interpersonal influences on Black modes of self-expression and identification—a reminder that women artists have a variety of resources at their disposal when crafting a public image and message. This was one of the key contributions of Dr. Keyes work to the study of hip hop: a classificatory scheme for understanding how women used a variety of personas (the queen, the lesbian, the fly-girl, the sistah with attitude) to take control over self-representation and complicate our understandings of what it means to be a Black woman. For both hip hop and society at large, what would it truly mean, as Queen Latifah and Monie Love rapped over 30 years ago, to put “Ladies First”?

Session Six: Mikko Kapanen, Amkelwa Mbekeni, H. Samy Alim, Samuel Lamontagne, and Chuck D

Around the World: Global Hip Hop Culture

On May 4th, 2022, for the sixth installment of the Hip Hop Initiative’s “Rap, Race, and Reality with Public Enemy’s Chuck D,” we focused our attention on hip hop around the world with special guests, Mikko Kapanen and Amkelwa Mbekeni, from Planet Earth Planet Rap (PEPR). Based out of Helsinki, Finland, PEPR focuses on hip hop worldwide beyond the mainstream and acknowledges the global culture and the people in it as participants, not just consumers. As part of Chuck D’s radio network, PEPR is hosted and produced by both Mikko and Amkelwa as they focus on multilingual hip hop from different corners of the world. PEPR is in the midst of their “Planet Earth Planet Rap - the Virtual World Tour,” where they are set to virtually invite special hip hop guests from around the world as part of a global conversation of hip hop music and culture.

Along with our guests from PEPR, Professor H. Samy Alim began the session by introducing a special surprise guest, the one and only Dr. Geneva Smitherman (Dr. G). Dr. G is the pioneering scholar of Black Language and one of the first to write scholarly work on the linguistics of hip hop culture in the 1990s. Alim cited her book, Talkin and Testifyin: The Language of Black America (1977), as the text that ultimately led him to make the connections between hip hop culture and Black speech in his own work, Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip Hop Culture (2006). It was an emotional moment recognizing the work of “the Elders” and showed how critical good mentorship is to the continued study of hip hop in academia.

“Professor Chuck,” as he is now affectionately known around campus, began by talking about American cultural hegemony and arrogance in relation to hip hop and the world. He talked about U.S. hip hop, mostly mainstream hip hop, and its “West vs. the Rest: mentality:” “A United States of America State of mind… we fall victim to saying we do the thing here, and everything else is over there.” But we as a hip hop community and folks like PEPR help combat that U.S.-centric ideology and show that the hip hop community is to be appreciated in its entirety. Chuck then stressed the point of geography and the importance of technology. With the constant change in technology, it has been easier to spread hip hop all across the globe from Cape Town, South Africa, to Paris, France, to Helsinki, Finland. This shows how the work of PEPR is vital to spreading all hip hop across the globe.

In another highlight of the evening, our very own Samuel Lamontagne, who, while contextualizing French hip hop within the colonial history and racial politics of France, presented a variety of French artists (Ministère AMER, Casey, Moha La Squale, and Lala &ce). He talked about how hip hop, an art form historically coming from the U.S. became a medium of expression for French racialized people – France’s post-colonial youth, in particular – to articulate their own struggles and experiences, too often overshadowed by glamorous Parisian clichés like the Eiffel Tower, the Champs-Élysées, Montmartre, and all those things Kanye West and Jay-Z rap about “in that song,” as Lamontagne added humorously. He emphasized the importance of not only acknowledging the presence of “Black people in Paris, but of Black people from Paris” – a history and a presence that rap allows to render visible. Relying on certain French rap songs as examples, he pursued his critique of dominant notions of Frenchness, which, as too often equated with whiteness, have excluded French racialized people from their belonging to this national category, as well as have erased centuries of racial exploitation and colonial extraction that contributed to make France what it is today. In concluding, Lamontagne replaced hip hop within a larger context, and reminded that beyond language barriers and national borders, music – and hip hop specifically – has been a central medium to build solidarity across the African diaspora, and beyond.

In conversation with Chuck, Lamontagne and Alim continued to discuss the racial politics of France and South Africa, and how larger political and economic contexts continue to shape the music and culture being produced, and how as Alim said, “Everywhere around the world, Hip Hop has been taken up by the most marginalized, as Chuck and Public Enemy said decades ago, to fight the power – from South Africa and France to Palestine and Brazil, they’ve all been influenced by Chuck D and Public Enemy.” Alim continued to share about groups like Prophets of da City, Black Noise, and many others who are fighting the power by reclaiming their languages, cultures, and histories from their colonizers. Relatedly, Amkelwa mentioned that consciousness-raising music like hip hop was important in South Africa especially during apartheid as it was a way for artists to express their political voice to their people. Mikko added that hip hop around the world, like in Europe, gives a better understanding of the political climate than mainstream media as these are ordinary people telling their stories and narrating their lives.

We closed out the session by talking with Mikko and Amkelwa about how PEPR helps with spreading global hip hop to a wider audience and making the listener a participant rather than a consumer. We look forward to next week’s session with Dr. Gaye Theresa Johnson.

Session Seven: Gaye Theresa Johnson and Chuck D

Hip Hop and the Futures of Black Radicalism

Wednesday, May 11, 2022, “Professor Chuck” engaged with UCLA’s own Dr. Gaye Theresa Johnson to discuss Hip Hop and the Futures of Black Radicalism, and centered on Dr. Johnson's analysis of hip hop, the work of Cedric Robinson, the Black radical tradition, and the concept of freedom. Dr. H. Samy Alim opened the session in his classic style by inviting students to think critically about the current state of our world: “What does the practice of Black radicalism look like in 2022? Why is it important to take Cedric Robinson’s work as a point of entry ‘to consider the history and ongoing struggle against racial capitalism, from the roots of Black radical thought to a shared epistemology of the present political moment?’” And then he added, “These two brilliant colleagues and friends are going to help us think through these questions and more, walking us through how the manifesto, the monograph, and I would add, the music, can be equal yet distinct sites where Black radicalism is reimagined.” Dr. Johnson opened up the conversation by stating, “I want to acknowledge the precariousness of this moment,” ushering the discussion into the topic of Blackness and hip hop.

Prof. Chuck said that people often say how much they love hip hop, but when he asks them if they love Black people, many folks get quiet, or provide answers ranging from “That is a racist question” to “What does race have to do with it?” Prof. Chuck was right on time, pointing out that love of Black culture does not translate to a love of the people who produce it. As Prof. Chuck put it, “People love everything but the burden,” meaning that the prospects of freedom and Black liberation are entirely outside the dominant imagination, where hip hop can be loved but Black people cannot.

Dr. Johnson continued by reframing the question, “Do you love hip hop?”, to include if you love something, how do you know, and how are you caring for it? Dr. Johnson urged us to think about how we carry the stories of our people within our bodies, how we honor the things that we love, even hip hop, by collecting the stories of our elders and working in a collective, as Prof Chuck and previous guests have reiterated. The collective is central to the genre. Prof. Chuck asked us to consider how we honor the pain associated with being Black, the struggle that so many Hip Hop artists rhyme about.

Bringing the conversation back to the work of Cedric Robinson, Dr. Johnson reminded us to think critically about racial capitalism and its functions by summarizing Toni Morrison’s famous quote, “The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being…None of this is necessary. There will always be one more thing.” Dr. Johnson held us all accountable for the work—or “doing the work” of Black liberation and freedom or, as she stated, “step aside so someone else can.” Black liberation is tied to the liberation of all people suffering, from Palestine across the globe to Ferguson. Again placing the freedom struggles in hip hop through the connection it brings as people worldwide align with Prof. Chuck’s most potent lyrics – “Fight the power.” As Dr. Johnson has written in the introduction to her book, Futures of Black Radicalism (2017, Verso; with Alex Lubin), “The individuals and communities who author and enact [the struggle for freedom] find themselves struggling amid multiple contradictions – between neoliberalism and democratic governance, between settler colonialism and the promise of marketplace participation. Therefore, freedom seekers and cultural workers, as they have with every new political conjuncture, have found it necessary to transform this work into more than an intellectual exercise – it is a critical practice.”

At the end of the evening, an undergraduate student asked, “What do we take away from this discussion? How do we do this in our own lives?” Dr. Johnson responded by telling the student that to be radical in this moment is to center Black life, to center what you know and what you are doing in this world. When you get off track, trust your community to bring you back. Rest when you need to, and reclaim time and space by slowing down and taking the time to do the work. Believe in your intuition, gifts, and beauty that you bring to the world.” Dr. Johnson reiterated that abolition and freedom “are not destinations but always and forever processes of how we engage the world and other people. We must always be in the practice of this as there is no endpoint.” Dr. Alim co-signed Dr. Johnson by commenting, “Yes, radicalism isn’t always ‘joining a movement’; it can be found in our everydayness. How do we engage the world, the people we encounter every day, the communities we are a part of?” We will surely pick up on these themes and more with next week’s special guests, Bryonn Bain and Maya Jupiter.

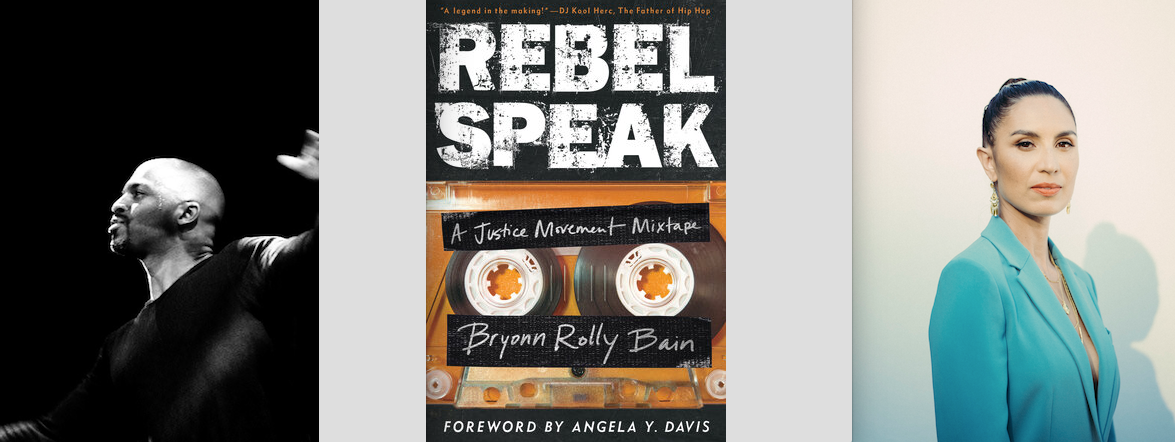

Session Eight: Bryonn Bain, Maya Jupiter, and Chuck D

Hip Hop and the Movement for Black Lives

On May 18th, 2022, the Hip Hop Initiative’s eighth installment of “Rap, Race, and Reality with Public Enemy’s Chuck D,” focused on the relationship between hip hop and the social justice movement for Black lives, featuring a dialogue with Maya Jupiter and UCLA’s very own Bryonn Bain. Maya Jupiter wears many hats as an activist, hip hop artist, mother, philanthropist, and co-founder of Artivist Entertainment, a L.A. based organization that centers on supporting and creating art that inspires positive social change. Originally from Sydney, Australia, Maya Jupiter now lives in Los Angeles where she serves on the advisory board at Peace Over Violence and also acts as a spokesperson for their Denim Day campaign. Similarly, Brooklyn’s Bryonn Bain is a jack of all trades as a writer, scholar, actor, hip hop theater innovator, author, poet, educator, artist and prison activist. Bryonn has done it all from founding prison education initiatives at NYU and UCLA, to producing and starring in the Lyrics from Lockdown, to publishing multiple books, including REBEL SPEAK: A Justice Movement Mixtape with UC Press’s Hip Hop Studies Series.

Chuck D began the class by recapping last week’s conversation around the social meaning of hip hop with Dr. Gaye Theresa Johnson and emphasizing that the momentum of our classroom discussions has only grown each week. Chuck D and Bryonn Bain started off by discussing doing work in prisons as Bain explained that he used his educational background to sneak in his social justice oriented work (similar to Maya Jupiter’s music video “Crumble,” which advocates for abolishing the prison industrial complex) in the back door and it helped that he wasn’t the “Malcolm X of Hip Hop” like Chuck D. Bryonn Bain then posed the question to the class, “How do we diffuse the symbolism of hip hop and prisons?” Maya Jupiter jumped in and further pushed this comparison as she explained that hip hop was her critical race studies growing up in Australia. She explained how hip hop “was the sound of struggle and oppression” which garnered much support from the racially minoritized youth across Australia, even causing them to rap in American accents at times.

The conversation then shifted as Maya, Bryonn, and Chuck D began discussing the Buffalo mass shooting with Chuck D pointing out how long it took for it to make national news. He pointed out how Black people are often blamed for the violence within their communities and in the lyrics of hip hop songs, yet, no responsibility on behalf of the state has been taken for the violence inflicted on the Black community. Critically discussing the convict lease system as a multibillion dollar industry, Bryonn Bain contextualized mass incarceration in the history of slavery. He expanded on prison abolition movement and related conversations he develops in his book Rebel Speaks: A Justice Movement Mixtape, in which he centers the voices and narratives of formerly-incarcerated and system-impacted people. Maya Jupiter echoed this powerful work by saying that “hip hop is a reflection of our culture and society right now. We are hip hop, and if there is violence in their lyrics it’s because that is where they are at.”

Going back to our week 1 discussion on defining hip hop, the conversation moved to how hip hop is art and that art can be artificial, a weapon, and medicine. Hip hop makes us feel deeper and acts as an alarm clock to wake us up as to the things happening within society. Chuck D concluded by asking the guests what they thought future technological developments hold for us? In light of the Buffalo shooting, Maya Jupiter also asked, are we as a society becoming desensitized to violence? She encouraged to grapple with the traditional indigenous Australian question, “What are we doing right now that’s going to impact people 7 generations from now?”

Session Nine: Adam Bradley and Chuck D

Hip Hop Poetics

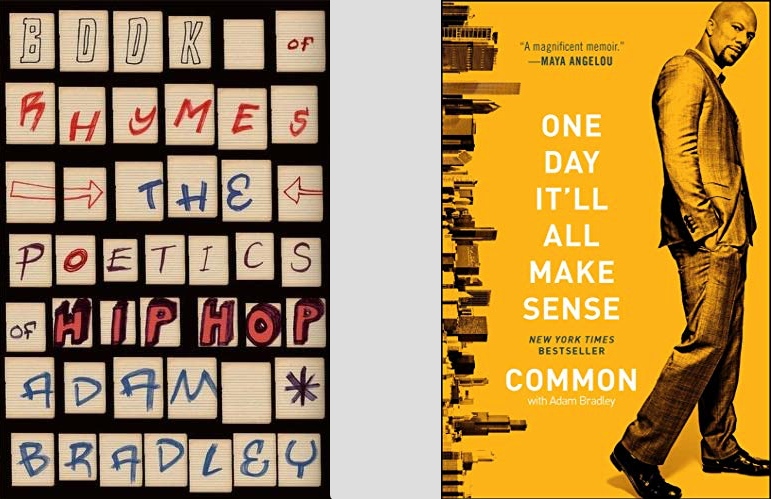

On Wednesday, May 25th, 2022, the Hip Hop Initiative’s ninth installment of “Rap, Race, and Reality with Public Enemy’s Chuck D,” featured best-selling author, professor, and UCLA Hip Hop Initiative board member, Adam Bradley. Samuel Lamontagne welcomed everyone to the virtual meeting by making a few important announcements before Tabia Shawel introduced Professor Bradley to the class. Dr. Adam Bradley is a professor of English and the founding director of the Laboratory for Race & Popular Culture (RAP Lab) at UCLA. He is a writer for the New York Times where he contributes essays and profiles on arts and culture. Bradley is the author and editor of six books, including Book of Rhymes: The Poetics of Hip Hop; The Anthology of Rap; and the New York Times bestseller One Day It’ll All Make Sense, a memoir on the life of rapper and actor Common. He has also written extensively on the literature and legacy of the novelist Ralph Ellison. Bradley’s latest book, The Poetry of Pop, unlocks the mysteries of the words, images, and sounds in popular music across genres, featuring the music of Bruce Springsteen, Beyoncé, and beyond.

Chuck D began the discussion by distinguishing the beat and the form while Dr. Bradley discussed the effects of poetic logic on flow and language. The two engaged in a lively dialogue on the transition between the performance of rap in the street versus how it is circulated through radio and media formats. While Dr. Bradley emphasized that flow reigns supreme in contemporary hip hop, Chuck D added that nowadays people “listen with their eyes,” as artists put so much emphasis on the visual dimension of their craft. When the conversation shifted to the fight to get hip hop scholarship published, Dr. Bradley revealed the gatekeeping issues he had to go through early in his academic career. Chuck D commended Dr. Bradley for his poignant contributions to the literary analysis of hip hop and stressed the importance to practice honesty and integrity.

Chuck D then asked what was the inspiration behind Dr. Bradley’s The Book of Rhymes and The Anthology of Rap. Regarding the first book, Bradley replied that his main objective was to legitimize the literary and lyricist dimensions within hip hop and show that rappers’ poetic approaches are just as valid as the classical works of institutionalized writers. For The Anthology of Rap, Bradley indicated a different approach as he was working with his editing partner Andrew DuBois. As he put it, The Anthology of Rap was like putting together a mixtape: he wanted to see generational and stylistic diversity between the songs and artists selected.

Chuck D took the time to ask Dr. Bradley about the writing of One Day It’ll All Make Sense, and how the book came from the relationship he was able to develop with Common. If their mutual agents facilitated the deal, Dr. Bradley then flew out to Los Angeles to meet Common. After spending time together and really getting to know Common, Dr. Bradley received the highest honors a biographical writer could hope for: Common’s mom telling Bradley, “that’s my son,” after reading the book. Dr. Bradley ended the class by telling Chuck D about the Laboratory for Race and Popular Culture (RAP Lab) at UCLA, a transdisciplinary research hub for the study of hip hop cultures, which looks to engage with the UCLA campus community and hip hop scholarship at UCLA.

Session Ten: Joan Morgan and Chuck D

Visual Art and Hip Hop

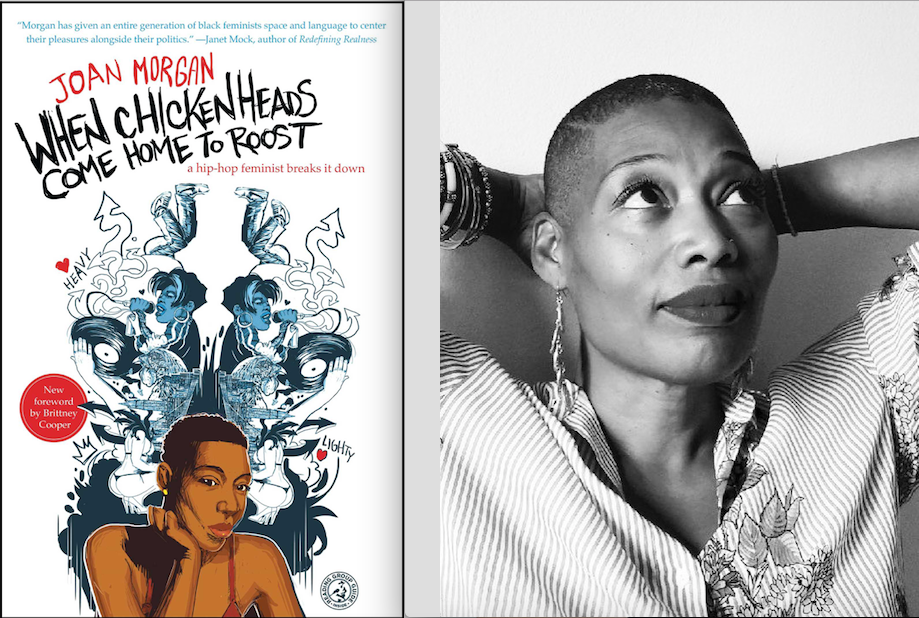

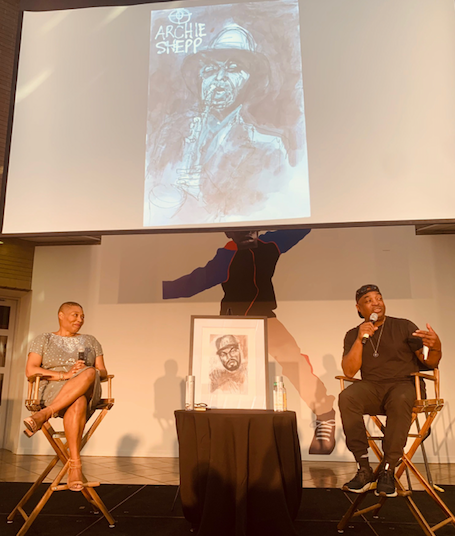

On Wednesday, June 8th, 2022, the Hip Hop Initiative’s tenth installment of “Rap, Race, and Reality with Public Enemy’s Chuck D,” welcomed the award-winning educator, writer, Hip Hop feminist, and journalist, Dr. Joan Morgan. Held at the California African American Museum (CAAM), the final session of the class focused on the visual dimension of hip hop, and featured the visual work of Chuck D himself. After a formal introduction by CAAM’s Alexsandra M. Mitchell, Professor H. Samy Alim discussed how the inspiration for the class with Chuck D took place in this very same room on March 11, 2020, during the Sweat the Technique event which featured legendary guests Rakim, Talib Kweli, and our very own Chuck D. Introducing Dr. Joan Morgan, Alim reminded the importance of her work and career, especially emphasizing her ground-breaking book When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: A Hip-Hop Feminist Breaks It Down, in which she coined the term “hip hop feminism.” Before welcoming Chuck D and Dr. Joan Morgan to the stage, Alim also acknowledged the essential work of Bunche Center Assistant Director, Tabia Shawel, and soon-to-be Dr. Samuel Lamontagne.

Starting the conversation, Dr. Morgan attested that Chuck was one of the few men artists who offered encouragement during her formative years as a journalist and scholar. The conversation shifted towards the 1990s with Chuck D recalling that this decade was a rough time and that Dr. Morgan’s work was necessary as hip hop was becoming a multi-million-dollar enterprise. Dr. Morgan related the corporate investment in hip hop to the idea of the gentrification in our current communities and how these financial demands, although needed, altered the nature of the culture. Professor Morgan also spoke about the shifting landscape of hip hop and how women had been “thrown out” during this period. These tensions regarding women in the culture left her feeling betrayed and questioning whether one can simultaneously love hip hop and be a feminist. She shared how a hip hop journalist could “catch a beatdown” by criticizing an artist but that Chuck D was gracious and would engage or “spar” with the writer, including contested exchanges with the late and beloved luminary Greg Tate.

The conversation shifted towards the stark differences between 1980s and 1990s hip hop. Professor Chuck discussed the generative power of hip hop culture, which would eventually be overshadowed by the influx of super cocaine and guns into inner city communities. He suggested that the start of the destruction of Black neighborhoods could be attributed to the “iso-ball” soloist mentality that became pervasive in hip hop during the 1990s. Both discussants agreed that The Fugees were an exemplary group that demonstrated the importance of having role players.

A central theme in the course has been Chuck D’s insistence that hearing music has become secondary to viewing visuals, and that consumers now “listen with their eyes.” He maintains that we need to get back to the point where the importance of listening is akin to the importance of reading the “fine print” of a contract. This led to an exchange where Dr. Morgan praised Chuck D for having both uncanny volume and flow as a rapper. As she compared the renowned boom of Chuck D’s rap voice to a “voodoo science,” Dr. Morgan insisted that Chuck D’s portrait art was striking for its ability to be an attenuation of that volume, a softer execution. She asked the audience if anyone knew Chuck was a visual artist which prompted Professor Chuck to say people didn’t “need” to know that about him because he didn’t want to be a rapper and visual artist. To him, the mindset of being a jack of all trades resembled an individual, capitalistic mindset versus the collectivity inherent to an assembly line of production. Dr. Morgan built off that idea by making the argument that people are taught to buy the arts because of the commodification of art in our culture.

Concerning his visual art, Professor Chuck spoke about his style being kinetic and the importance of working from the inside of a piece to the outside. He reminded us all that art is a facsimile to life and not necessarily a 1:1, photo realistic recreation. He urged that artists work from and through what they see, hear, and feel. This unique ability of the artist can be compared to early hip hop where practitioners had to form their own identity, “imitating but never duplicating.” During the Q&A, Professor Chuck also shared a moving story about the inspiration behind the lyrics of “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos” and hammered home the need to manage gadgetry and technology as opposed to allowing it to control and master us. After sharing a poignant story about assuaging the pain of losing his father in 2016 with powerful ayahuasca sessions, Chuck D encouraged us all to “get high on art,” which has led him to become a prolific artist. Chuck D would close with wise words about the need for our communities to pay attention and do what’s good for us, or else risk having the “chickens come home to shoot.”

This text was collaboratively written by members of the UCLA Hip Hop Studies Working Group, including H. Samy Alim (Session 1), Casey Wong (Session 2), Dexter Story (Session 3), Leroy Moore Jr. (Session 4), Mercedes Douglass (Session 5), Erick Matus (Session 6), Stephanie Keeney Parks (Session 7), Taylor Reed (Session 8), Alexander Williams (Session 9), Dexter Story and Alexander Williams (Session 10).

All photographs and editing by H. Samy Alim, Samuel Lamontagne, and Tabia Shawel