Collaboration, Fieldwork, and Film

Each month, Ethnomusicology Review partners with our friends at Echo: A Music-Centered Journal to bring you “Crossing Borders,” a series dedicated to featuring trans-disciplinary work involving music. ER Associate Editor Leen Rhee welcomes submissions and feedback from scholars working on music from all disciplines

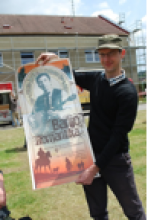

Photo of Lee Bidgood at the White Stork bluegrass festival in Luka nad Jihlavou, Czech Republic after a screening of the film Banjo Romantika, 2013, taken by Zdeněk Hrabica.

Lee Bidgood is a musician and scholar working among the US string band, early music, the practices of theology and music, and borders and thresholds. Assistant Professor in the department of Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University, he teaches a graduate course on Ethnomusicology and Appalachia as well as undergraduate classes in Bluegrass, Old Time, and Country Music Studies. He also leads a mandolin orchestra and coordinates the MA program in Appalachian Studies.

* * *

I never imagined that I would help produce a documentary film based on my ethnographic fieldwork. Meeting documentary filmmaker Shara Lange during new faculty orientation at the university where we were both newly hired eventually led to our film Banjo Romantika (2013)—a full-length feature based on my research on bluegrass music in the Czech Republic, in which I play a key role as writer, producer, and on-screen character. Taking part in this film project has led me to consider how film enriches relationships with field colleagues, providing new opportunities for teaching and learning. I find that collaborations like ours can reframe and extend ethnomusicological work in productive ways.

As I began fieldwork exploring bluegrass-related music making in the Czech Republic I captured video and audio recording, but never spent serious money on a recording rig or gained training in producing high-quality media materials. I focused on presenting that world in writing. It did not occur to me that others might find a version of any of this media interesting, compelling, or useful. In my mind the footage that I had collected since first traveling to the Czech Republic in 2000 was "pure research" and existed solely to support my work as a fledgling scholar. With this mentality of “private scholarship,” I was somehow satisfied that the low-quality video of performances, workshops, and band rehearsals which I recorded would remain in my private hoard. MiniDiscs, MiniDV tapes, and hard drives full of media files, with only small excerpts of transcribed speech dusted off to appear in my academic writing. In this period when I saw films like Throw Down Your Heart (Paladino, 2008) I was cautious, not sure that such polished productions could really be useful parts of ethnomusicological discourse or—at a more basic level—of fieldwork.

While in the Czech Republic in 2002-3 and 2007-8 I took many photographs, but without a clear strategy for using them for my work. My project working with Czech bluegrassers contained a wealth of visual dissonance and creative recontextualization that seemed difficult to capture without visual media—Czech use of the Confederate flag or of US military jeeps, for instance (see examples below). I slowly began to consider how these visual elements could be a substantial counterpart to my writing. I also realized that part of my hesitancy was that I didn’t have the skills needed to create compelling media.

Photo 2 - “Rebel” in the audience at the 2003 Banjo Jamboree bluegrass festival, the oldest event of its kind in Europe, first held in 1972. Photo by the author.

Photo 3 - Jeep owned by a bluegrass musician in Luka nad Jihlavou, Czech Republic, 2009. Photo by the author.

Before we met in 2010, Shara Lange’s growing body of documentary work already showed a keen and insightful approach to representing unexpected juxtapositions and international movements on film. Her film The Way North (2007) provides a sense of the struggles of Maghrebi woman who have settled in Marseille; and The Dressmakers (2013) addresses a variety of approaches to making clothing (craft, couture, and manufactured) and the ways that these kinds of work are valued in contemporary Morocco.

I had a healthy respect for the value of films such as these when I met Shara in 2010, but little vision for how or why I might take part in a documentary project. I hadn't read much on ethnomusicological film in graduate school, but remembered Richard Schechner's description of filmmaker Gardner and linguist Staal heading a project to stage the Agnicayana ritual and create the resulting film, Altar of Fire (1976). I remember thinking that the team’s collaboration was a useful and productive marrying of disciplines. I also retained Schechner's critical edge in discussing the problematic "mess" of "restorations" such as documentary film, which aren't as "easily recognized as interpretations" as academic writings (Schechner 1985, 63). This was my objection to films like Paladino’s, which muddied the distinction I felt divided "entertainment" and "document" per Feld's survey (1976, 293) of ethnomusicological and visual communication.

Photo 4 – Shara Lange shooting the Czech band Reliéf at the Hradešinské Struny festival, 2011. Photo by the author.

When Shara and I set out to film in the Czech Republic, my lingering sense of a scholarly ideal led me to impose a research-design structure to our slate of scheduled interviews and visits to performance events. This stance quickly met with the practicalities of fieldwork (which ranged from me not being able to successfully work the sophisticated camera, to a hardware glitch garbling a key bit of interview audio, etc.); at a more foundational level, however, my sense of the project sometimes conflicted with Lange's goals as a filmmaker. Although dedicated to an observational perspective, and thus to a transparent presentation of her subjects, she also emphasized to me the importance of a dramatic "through-line" to the film, and spoke of the people we were filming not as colleagues or subjects but as "characters." As I pushed for more and longer filmed interviews (thinking that more words from “characters” mouths would give them more agency and provide more information) she sought evocative moments, interactions, and scenes.

As we worked to edit our footage for the film, I continued to read about film and ethnomusicology, starting with Feld’s 1976 article on the subject. I appreciated the advice and anecdotes from Zemp (1990), whose account of filming Swiss yodelers and “yootzers” provided ways of considering ethical concerns that were more immediately germane to our film project than the IRB protocols that I was also assimilating at the time. Simone Kruger’s consideration of “Ethnomusicological uses of film and video” (2009) provides even more practical advice, particularly on using film and video in teaching and in other public presentations of scholarly work.

After filming I was still coming to grips with this new way of thinking about this framing of my field colleagues and my work, when I was thrown a new twist - I was going to become a character myself. While our location shots had left me out of the frame for the most part, we needed a presence to help string the film's scenes together. We decided to shoot footage of me taking on the role of musician and emcee at a concert organized for this very purpose at a music venue in Tennessee. At the concert I led a group of musicians through performances of Czech bluegrass-related songs sung in both English and Czech, providing explanations between songs.

This clip includes footage shot at the Down Home in Johnson City, TN in 2012 as well as material shot at Czech banjoist Marko Čermák’s cabin outside Prague in 2011.

Neither Shara nor I wanted to include voice-over explanations, as we wanted to convey the variety of interpretations of Czech bluegrass that we recorded during our fieldwork. Put into a role on screen, I still remained a privileged interpreter and arbiter. However, as a character providing explanations, I was captured on screen talking, mumbling, and explaining without a script. I also joined my Czech colleagues in creating (or rather, re-creating) Czech bluegrass on film. We were still determining the representation of Czech bluegrass and bluegrassers, but within our “restoration” of a Czech bluegrass performance. By making me a character among other speaking and interpreting characters, we hoped to offer a diverse set of views, not just one authoritative voice. While our staged “live concert” ruse is not without problems, it provided a way to move forward in making our footage into a film.

The most significant result of the documentary on my continuing fieldwork among Czech bluegrassers is an increased engagement with my projects. Discussing my plans for an English-language academic paper or monograph has never quickened my colleagues' pulses. Seeing or hearing about the film has led many Czech people to contact me with questions, concerns, and feedback that I have been trying to elicit for years through more traditional means. We plan to broadcast the film on a television station in the Czech Republic, launching it into the wider discourse among fans and non-fans of bluegrass there.

Photo 5 – Banjo Romantika screening at the Banjo Jamboree bluegrass festival in Čáslav, Czech Republic, 2013.

One unexpected dividend of my role as a “character” emerged when I screened the film in the Czech Republic in 2013 for an audience of bluegrassers at the Banjo Jamboree bluegrass festival. Several colleagues responded animatedly after the film to my request for comments, saying that they understood the film as my attempt in representing Czech bluegrass from the moment they heard my voice singing a well-known Czech song about bluegrass in the film’s first scene. As a character in the film, I was doing for their musical practices what they have been doing for decades with U.S. Bluegrass practices!

Now, years after the rush of filming, the honeymoon period is over. We find ourselves working to understand the process of public television stations' selection of content (we are first seeking television broadcast of our film in the US), learning from Shara about the ways that you have to cultivate knowledge about a film project through careful propagation and cultivation of relationships with people and entities. New processes were added to (and, sometimes, in potential opposition with) my ethical concerns in fieldwork. We have had to negotiate musical publishing rights, work with a film industry lawyer, and trade my consent agreements for "durable master licenses" that grant us as filmmakers unconditional rights to the use of our recorded material in all media.

There are fun parts of the film project, too: we make and sell "merch," go on tours to promote the film, apply to and attend festivals. Sometimes I feel like part of the start-up of an independent band, with boxes of DVDs and t-shirts stacked in my foyer at home. These productions might seem peripheral, but they—and the film—continue to slowly circulate among Czechs with whom I work, and spread to those outside the circles of my immediate fieldwork connections. Facebook and other social networking sites have proven key media in bringing these people to my attention, and providing a platform for conversation and possible future fieldwork. As I am becoming less able to travel and spend extended periods of time in the Czech Republic due to family and work, I’ve found a new set of avenues for mediated fieldwork.

Photo 6 - “Zdeněk Roh, Czech banjoist and luthier featured in Banjo Romantika, with film’s coproducers Shara Lange and Lee Bidgood (L-R) at the Nashville Film Festival, 2014. Photo by the author.

Collaboration remains the core and generative engine of this project. The film could not have happened without Shara's filmmaking expertise: she shot, edited, and guided the entire process. At the same time, my social contacts provided us with essential welcome and support. This kind of wide community involvement and interaction remains central to the project. Question-and-answer sessions after screenings of the film have created small community discourses including voices from Czechs, Americans, filmmakers, musicians, scholars, fans, and total strangers.

These fruitful discussions reassure me that this film has found itself in a productive position between both Shara’s and my own field of work. It is both a polished media product due to Shara’s care and expertise, while at the same time it is a central part of my ongoing ethnomusicological work in collaboration with institutions, field colleagues, and students. Working in-between disciplines and outside of academic limits structurally bears out my ethnomusicologically informed goal to staudy what happens between people. Our work together on the film, and the reception and ongoing mediation of our project has reinforced my emerging conviction that music, like film, is something that lives "in-between," emerging amidst and among participants.

* * *

Schechner, Richard. 1985. Between Theater and Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Feld, Steven. “Ethnomusicology and Visual Communication,” Ethnomusicology 20:2 (May, 1976), pp. 293-325.

Kruger, Simone. 2009. “Mediating Fieldwork: Ethnomusicological Uses of Film and Video,” in Experiencing Ethnomusicology: Teaching and Learning in European Universities. Burlington: Ashgate. pp. 189-208.

Zemp, Hugo. 1990. “Ethical Issues in Ethnomusicological Filmmaking,” Visual Anthropology 3:1, pp 49-64.