A Finnish Medley: Forging Folk Metal

In 1990, the Swedish black metal band Bathory released Hammerheart, in which they turned from worshipping Satan and cursing Christ to praising Odin and longing for Valhalla—thus Nordic folk metal was born. Musically, Hammerheart does little to remind the listener of traditional Swedish music, but the lyrics mark a definitive, nostalgic turn toward a heroic Viking past.

Across the Gulf of Bothnia, Finnish metal bands similarly began to take an interest in turning to their past, particularly the Kalevala - Finland’s national epic. Incorporating both sounds and words from the Kalevala tradition, they gradually built a robust metal sub-genre that has achieved remarkable success abroad. My research on Finnish folk metal has focused on the specific ways in which these bands have used and adapted traditional materials in their music, and I submit that their practices fall in line with the way the Kalevala itself was put together in the 1800s by Elias Lönnrot.

The Kalevala, though heralded as the “lost national epic” of Finland, never existed as a unified whole until the 1800s. Rather, the Kalevala as known today represents the collection, manipulation and organization of an ancient oral tradition according to 19th century National Romantic sensibilities. While each of the individual poems that Lönnrot collected during his fieldwork was authentic, their editing into a single, more or less unified storyline is his work. Moreover, the poems that did not make it into the Kalevala fill some 33 volumes, comprising one of the world’s largest folklore collections.

Nevertheless, the Kalevala played an important political role in the formation of Finnish national identity; Finland was under Russian control at the time of its publication, and had previously spent centuries under Swedish rule—Finland did not exist as a sovereign nation until 1917. In 1835, the appearance of the Kalevala gave the Finns a piece of literature of great historical and cultural value, an epic poem that proved the richness of Finnish cultural heritage. Today, Finnish artists of all genres continue to draw on the artistic tradition that gave them the Kalevala: the adaptation and reconfiguration of traditional stories and materials to changing aesthetic times.

So, to what extent does Finnish folk metal draw on identifiable traditional elements? Unsurprisingly, the answer is rather complex and adaptations vary from vague references to metal covers of traditional songs. Perhaps the most famous of the Finnish folk metal bands, Amorphis, is known for their direct use of Kalevala poems as a source for song lyrics; their 1994 album Tales from the Thousand Lakes sets Kalevala passages for all but two songs. Here, however, I’d like to take a closer look at just two recent examples from the work of another Finnish folk metal band, Ensiferum (Latin: “Sword bearer”).

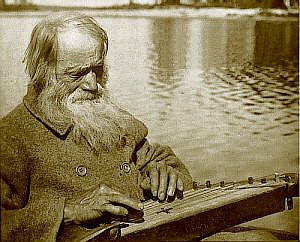

Traditional Kantele

Founded in 1995, Ensiferum’s music represents a folk metal style in which musical signifiers of “folk music” are prominent in the texture. These features include use of 6/8 meter, minor pentatonic melodies, and use of traditional instruments such as the hurdy-gurdy, nyckelharpa, and flutes. Most importantly, their first few albums made frequent use of the kantele - a type of zither recognized as the Finnish national instrument, based on its significance in the Kalevala. (Listen, for example to “Old Man;” the kantele comes in around 4:45).

Vocals are generally growled, with sung passages occurring in some songs, often as a chorus in which all band members sing together. In general, Ensiferum's lyrics deal with Viking and battle imagery, and the glorification of the heroic ideal; a typical song might include riding into battle or sailing to a distant land, praying to the gods for protection, and dreaming of Valhalla. Some songs allude to Kalevala material, though exact connections are difficult to make. It is only in their two most recent albums, From Afar (2009) and Unsung Heroes (2012), that they have incorporated short Kalevala passages into the lyrics for a few of their song. Previously, however, their EP Dragonheads (2006) included metal performances of three Finnish folk songs. Thus, Ensiferum’s incorporation of traditional elements runs the gamut from direct and unmistakable, to projection of general Nordic themes, including Viking themes that have no actual historical connection to Finnish culture. Folk metal offers a performance of Finnishness, but one that is flattened into a set of images easily portrayed by the heavy metal idiom, and leans toward nostalgia for a Romanticized, heroic past, and is thus almost reduced to caricature.

Modern 38-string Kantele

The song “In My Sword I trust” from their 2012 release Unsung Heroes is a good example of both Ensiferum’s typical musical style and their tendency to conflate specifically Finnish traditional elements with Viking themes.

The song’s lyrics blends Viking themes with a passage selected from the Kalevala:[1]

Many men have crossed my way

Promising peace and my soul to save

But I've already heard it all

I've seen what they made with their freedom

But I, I have no need for your god

The shallow truth of your poisonous tongue

Brothers, it's time to make a stand

To reclaim our lives

Because only steel can set us free

(Chorus)

Rise my brothers, we are blessed by steel

In my sword I trust!

Arm yourselves, the truth shall be revealed

In my sword I trust!

Tyrants and cowards for metal you will kneel

In my sword I trust

'Til justice and reason we’ll wield

In my sword I trust

The sword that shimmers in my hand,

Do you have the mind to eat the guilty flesh?

To drink the blood of those who are to blame?

The time of change is here, unveil your blade!

(Chorus)

Leave your souls to your gods

Kneel, obey, follow their laws

Deceit, subjugate, cherish their greed

Disdain verity, glorify futile faith

(From Kalevala)

O Old Man,

Bring me a fiery fur coat

Put on me a blazing shirt

Shielded by which I may make war

Lest my head should come to grief

And my locks should go to waste

In the sport of bright iron

Upon the point of harsh steel

(Chorus)

The lyrics written by the band present a Viking-themed protest against the Christianizing of the North; this theme of rallying for battle (whether a defensive or offensive one) pervades folk metal. The verses are growled, but the choruses are sung in a call and response pattern to a simple folk melody by all the band members; the leader calls out to his army and they respond, “In my sword I trust.” These sung choruses contribute immensely to the creation of a folk music ambiance, as they emphasize the group over the individual vocalist and provide a counterpoint to the screamed vocals in the verses that are more typical of metal music. The video shows the band in their typical live performance garb of (historically inaccurate) kilts and war paint, inside the walls of a medieval-looking castle, alternately playing their instruments and brandishing axes and swords; these anachronisms and temporally conflicting images are also typical of folk metal performance.

The passage with lyrics from the Kalevala comes in near the end of the song, around 4:15, accompanied by an abrupt upward key change. This passage is growled by the lead vocalist, backed by a minor folk melody, variants of which appear frequently in their songs. The key change sets this portion of the song apart from the rest, but the repetition of the melodic pattern begun about thirty seconds earlier provides continuity.

The lines Ensiferum has chosen come from one of the few actual battle scenes in the Kalevala.[2] In Runo 43, “Battle at Sea,” Ilmarinen and Väinämöinen battle Louhi (mistress of Pohjola, literally “the North,” but a sort of hell in the Kalevala) for possession of the sampo, a magical mill of sorts that produces grain, gold and all manner of good things for whoever has it. What is interesting about the choice of these eight lines is the line that has been omitted. In Keith Bosley’s English translation, this passage begins:

O Old Man, God known to all

heavenly Father

Bring me a fiery fur coat...

Scholars of Finnish folklore have noted the influence of Christianity on traditional Finnish poetry. While the Christianizing of Finland began in the 11th century, paganism persisted in rural areas into the 16th century, though without total exclusion of Christian concepts. Many poems in the Finnish folklore collection show the influence of Christian ideas, either through insertions or reinterpretations, or in some cases, the addition of passages that mock the “weakness” of the pagan gods.[3] In this particular passage, the Kalevala’s shamanistic hero, Väinämöinen is conflated with the Christian God. Ensiferum has deleted this conflation to make the words fit the song’s pagan theme, whereby they return Väinämöinen to his former status of human with magical or shamanistic powers. Their decision to de-Christianize this passage continues a process of adjusting this material to contemporary aesthetic goals that has been going on for hundreds of years, and also embraces a glorification of Nordic paganism common in folk metal.

“In My Sword I Trust” is typical of folk metal in that it grafts the “folk” elements onto the metal sound and performance style. To see what happens when this process is reversed, however, let’s have a look at Ensiferum’s “Finnish Medley.”

This five minute track strings together three traditional Finnish songs into one piece and add electric guitars and heavy metal drumming. Women sing the first song, “Karjalan Kunnailla,” (“On the Hills of Karelia”) an ode to the beauty of the Karelian landscape, in a slow 6/8 that is close to the tempo of traditional performances. The second song, “Myrskyluodon Maija,” (“Maija of the Stormy Island”) is an instrumental with a slow, lyrical section and a contrasting energetic section with alternating 5/8 and 6/8 meter. Ensiferum performs only this faster section, before moving on to “Metsämiehen Laulu,” (“Hunter’s Song”) an upbeat folk song sung by a men's chorus, mostly in 4/4 with a few measures of 6/8 thrown in. Sonically, the end result is what I would call “metal folk” rather than “folk metal,” in an attempt to express that the melody, repetitive strophic structure of each of the songs, and group/chorus performance style of the folk songs makes them easily recognizable as such; the addition of heavy metal instrumentation contributes a new texture.

“Finnish Medley” does not typify folk metal or even Ensiferum’s music. However, it does play an important role in performing both the band’s Finnishness and their ability to engage with traditional materials, lending legitimacy to their more metal-focused songs. Moreover, the idea of “medley,” with its implication of creating a new whole in which the parts are still visible, largely summarizes how Finnish folk metal functions more generally: traditional elements are freely blended with a contemporary musical style and a generalized idea of the Pagan North. The rough edges left between these parts show a living tradition, which artists continue to interpret and present in new ways, and help provide folk metal with its energy and widespread appeal.

Olivia Lucas is a PhD candidate in music theory at Harvard University. She is currently completing dissertation fieldwork on extreme metal in Helsinki, Finland. She also researches the fringe movements of extreme metal in North America, and temporality and rhythm in a wide variety of musics.

Sources:

Kuusi, Matti, Keith Bosley and Michael Branch. “Introduction.” In Finnish Folk Poetry: Epic: An Anthology in Finnish and English. 1997. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. pp. 52-6

Lönnrot, Elias. The Kalevala. Trans. Keith Bosley. Fwd. Albert B. Lord. New York: Oxford University, 1989.

[1] Lyrics found at http://www.darklyrics.com/lyrics/ensiferum/unsungheroes.html#2. Accessed April 19, 2013

[2] That the band chooses to use an English translation of the Kalevala is in itself remarkable. I don’t have room to thoroughly discuss this issue here, but in a simplistic sense, this decision supports their drive for international visibility.

[3] Kuusi, Matti, Keith Bosley and Michael Branch. “Introduction.” In Finnish Folk Poetry: Epic: An Anthology in Finnish and English. 1997. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. pp. 52-6