Freetown Soundscape: Chosan’s Love Song to Sierra Leone

Cellphone video footage captured one of my trips across Freetown, Sierra Leone’s capital city, in the back of a khekhe (a covered motorized tricycle). My husband, Jerry, was candidly explaining that we were traveling through Aberdeen, one of Freetown’s beach communities. While he spoke, pedestrians walked along the sidewalks hauling parcels and bags. The sounds of motorcycle engines roared as drivers darted down the roads. A rattling white trotro (minivan) zoomed past in the opposite lane. People shouted to amplify their voices over Freetown’s buzzing soundscape.[1] Our driver repeatedly honked his horn to attract subsequent passengers for our khekhe, hoping to gain maximum profits and riders for his route that day. Jerry continued describing Aberdeen and the driver quickly verified our final destination.

A few months before this Freetown khekhe ride, I was standing in New York City talking to Sierra Leonean born emcee Chosan. He emigrated to the United States after residing in the United Kingdom. Chosan’s music largely reflects his journey within the Sierra Leonean diaspora – communities of Sierra Leoneans spread around the world (Tucker 2013). He has used his experiences to create four independently released albums – Diamond in the Dirt (2008), Till I Touch the Sun (2013), Glare La Musica (2017), and Glareification (2021) – through Silverstreetz Entertainment. Glare La Musica features his track “Say It Again,” an ode to the people of Sierra Leone.

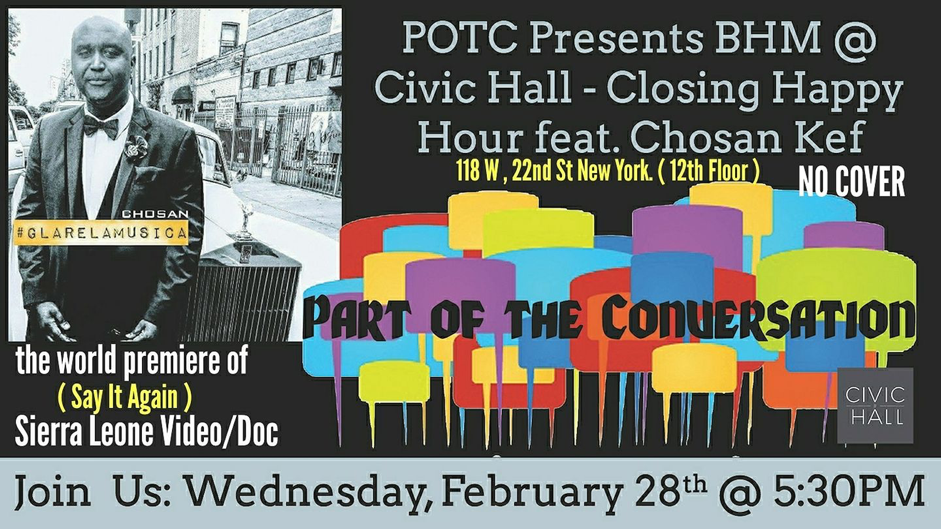

In February 2018, Chosan debuted his music video for "Say it Again" at the venue Civic Hall in Manhattan.

The viewing was, in his opinion, the completion of a full circle experience of filming videos in significant places in his life – the United States, the United Kingdom, and Sierra Leone. Chosan released his video for the track “N18,” which used the postal code for the community where he grew up in London. Yet, Chosan still wanted to film a video in Freetown and return to his birthplace. He accomplished this with “Say It Again” and its display of the vibrant cityscape.

Image 1: Promotional image for Chosan’s video debut for “Say It Again.” Image permissions granted by the artist.

Scenes from “Say It Again” illustrated many of Freetown’s quotidian activities. Chosan showed viewers the city center where people were hurriedly walking. Other shots from the video depicted rows of corrugated metal dwellings and the stretches of dirt roads in between them. Additional shots showed more spacious homes as well as some of the newer hotels that were constructed for the growing number of tourists visiting the city. There were coconut water vendors, fishermen pulling in their nets, women carrying babies on their backs, and crowds squeezing their way through the city marketplace. The video revealed the seemingly endless flow of interactions in Freetown – a city which I had not been to in more than three decades.

After Chosan debuted his video, he asked me a question that resonated with me long after it was posed: “What do you remember about Freetown?” I had flashbacks of going to the beach with my family, running along the sand, and tumbling down into the water among the ocean waves. There were endless hours of playing with my cousins on the veranda at our family home. I also had lingering memories of staring at the towering cotton tree out of the rear window of a car during a trip to town. However, these scenes felt as if they were steadily fading. Nevertheless, something in the “Say It Again” music video reignited them and I felt an urge to return to Freetown.

Before viewing “Say It Again,” I spoke with Chosan about his December 2017 trip to Freetown. He spent time at his mother’s home with relatives, connected with a local videographer, and began filming the video. Chosan admitted that there were several unexpected aspects of the video shoot. Moreover, he only had two days to film across all of Freetown. Nevertheless, Chosan was able to capture scenes from most parts of the city. His enthusiasm and excitement recounting the experience made me want to plan a trip to Freetown. I was scheduled to present at a conference in Accra, Ghana in August 2018, so I contacted my cousins and arranged to visit my family in the ensuing weeks. Once I reached Freetown, I was instantly immersed in the sounds of the city.

This article explores Freetown’s sounds and analyzes how they contribute to Chosan’s video for “Say It Again.” I will draw upon interviews with Chosan about the creation of the video and his time in Sierra Leone. Furthermore, I will include details from my own travels within Freetown in August 2018. This will offer two perspectives about the sounds of the city and how they contribute to a multisensory experience. This description of the city will support many of the images and scenes that are depicted in the “Say It Again” video.

Chosan and I started collaborating in November 2014. He had recently released the track “Find the Cure” addressing the impact of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. A few months earlier, I returned from getting married in Liberia while cases of Ebola infection were on the rise. I contacted Chosan to see if we could arrange an interview to speak about “Find the Cure.” We scheduled to meet at Covenant House, where Chosan was employed at the time. Once we started our interview, Chosan told me stories about the greater purpose of “Find the Cure,” which was to increase public awareness about the health crisis and to expand knowledge about how communities were responding to it in Sierra Leone. He also addressed matters such as Sierra Leonean identity, diaspora communities in the United Kingdom and the United States, as well as his role recording the narration for Kanye West’s Grammy Award-winning track “Diamonds from Sierra Leone.”

Our preliminary interview led to countless conversations over the years as well as investigations of several other songs that Chosan released. I continued speaking with him as he released his album Glare La Musica (2017) that featured the aforementioned songs “N18” and “Say It Again.” During an October 2018 conversation, Chosan shared that “Say It Again” was a “hard edged love song” for Sierra Leone (Chosan, personal communication, October 14, 2018). He explained the song is about telling stories directly from Sierra Leone and not hesitating to repeat them or say them again. “No matter how many times you have to say it, say it again,” he stated. “We’re talking about our stories, our plight” (Chosan, personal communication, October 14, 2018). The stories that he mentions are represented in the images, lyrics, and sounds of the city included in the video for “Say It Again.”

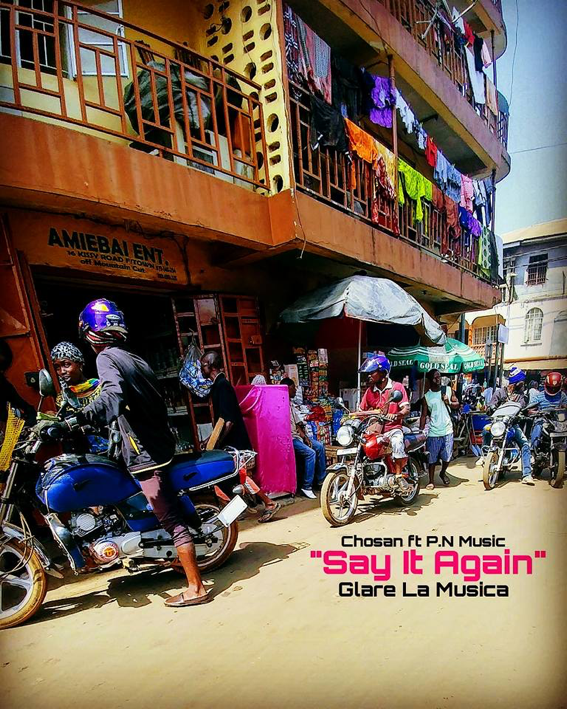

Image 2: Promotional image for “Say It Again.” Image permissions granted by the artist.

The video begins with a boy running down a dirt road in one of Freetown’s residential areas. He is sprinting as fast as he can, dashing through the community. There are subsequent aerial shots of Freetown and its accompanying sounds. However, when the boy reaches his home and opens its gate, he rushes over to a radio sitting on the ground. He quickly presses a button that causes music for “Say It Again” to play. Viewers are transported from this home to Freetown’s broad cityscape that is humming with activity. Chosan is shown flagging a khekhe. He boards the vehicle, the driver pulls off, and the singer PN starts singing the chorus (“All that I’m trying to say/ It comes out sounding the wrong way/ How can I make it sound right/ I’ll say it again if you like”).

The chorus of “Say It Again” was one of the major factors motivating Chosan to record the song. During one of our phone conversations, Chosan told me that he first heard the track during a trip to London. At the time, it was a love song that the artist PN intended to release (Chosan, personal communication, October 14, 2018). In the song, PN professes his enduring love for his partner. He attempts to ease their doubts about his fidelity by reiterating his feelings and saying it again. Chosan reimagined the song with producer Lord Itill as a way to tell the story of his relationship with Freetown. He elaborated on his song selection in a message that he sent me in November 2018, stating:

After hearing numerous beats (I’d say twenty or thirty), I came across this one and it just instantly struck a chord with my spirit. I told him that…he could take off his verses and just leave the hook. When I got back to New York, we rearranged it and…we sampled his hook. So the original song was about a guy that I guess keeps messing up and then he’s apologizing – trying all different ways of apologizing, but it keeps on coming out kind of wrong or he can’t put his words together, but he’s going to try again. So that’s where…the title came from – “Say It Again.” So even though he said it before, he’s going to say it again. I switched it to [mean that] speaking up for the truth and for the people gets tiring and gets weary, but you’ve just got to say it again and keep going and say it again. Hence, Itill’s intro in the beginning kind of sets up the tone for the song and sets up the tone for the hook. Basically, my interpretation of [the phrase] say it again is…no matter what’s happening, just keep standing up for the truth and saying it again even if you’re tired; even if the people seem like they’re not listening (Chosan, personal communication, November 9, 2018).

Chosan opens the track by asking, “Who’s going to tell our stories/ If we don’t tell ‘em” (Chosan, “Say It Again,” 2017). Then, he shifts to the theme of love. Chosan rhymes about the citizens of Sierra Leone and the treasures contained “in the heart and the spirit of the people” (Chosan, “Say It Again,” 2017). Chosan's quotes included at the beginning of "Say It Again" reflect ethnomusicologist Steven Feld's discussion of storytelling in his research on jazz music in Accra, Ghana. Feld proposes that stories can be used as an analytic mechanism. He finds:

Stories create analytic gestures by their need to recall and thereby ponder, wonder, and search out layers of intersubjective significance in events, acts, and scenes. Stitching stories together is also a sense-making activity, one that signals a clear analytic awareness of the fluidity and gaps in public and private discourses (Feld 2012).

Feld wages that stories function as “rearview mirror reflections; they are the mode of remembering things past, of resisting closure, of embracing life as reverberation” (Feld 2012). Stories become fixtures in his writing about cosmopolitanisms in jazz within Accra. Feld’s stories offer a foundation to the work appearing in his book and exemplify their role in ethnographic work.

Chosan’s stories about Sierra Leone are contained in the assorted representations of the city’s sounds. His interpretation of the city’s soundscape mirrors the work of anthropologist Michael Stasik. Stasik conducted a study about sound culture in Freetown that resulted in the publication of his thesis, Disconnections: Popular Music Audiences in Freetown, Sierra Leone, for the University of Leiden. In an article, “How to Dance to Beethoven in Freetown” (2017), Stasik investigates the distinction between noise and music in Freetown, pointing out the relative loudness of sounds across the city. He draws upon seven months of fieldwork in Freetown where he conducted focus group discussions, interviewed artists, and incorporated his own sonic studies of the city. Stasik combines his anecdotal accounts from the field with the works of numerous anthropologists, ethnomusicologists, and musicologists. He evaluates the effects of music played loudly through stereos and sound systems and how it is layered upon other parts of the soundscape. Stasik calls it an “urban symphony” and an “urban ballet” (Stasik 2010:12-13). Stasik held conversations with a businessman who deemed Freetown’s music “noise” as well as a Canadian NGO worker who commented that there is no “decrescendo” in Freetown because it is “just always loud” (Stasik 2017:11). These opinions about Freetown confirm Stasik’s declaration that his ethnographic research was intended to “reflect the diverse intersections, interactions, and contradictions between Freetown’s social polyphony and its musical counterpart” (Stasik 2017:11). He presents the range of different sounds in the city.

Apart from these debates about music and noise, Stasik traces the evolution of stereos like the one seen in the opening scenes of “Say It Again.” He writes:

Small, battery-run radio receivers have been imported and sold in quantity since the early 1980s. These radios, however, emitted sounds of moderate volumes only. This changed from about the late 1990s, as the availability and affordability of larger – and louder – electronic playback devices (comprising primarily of cassette, CD, and VCD/DVD sets) in Freetown increased significantly (Stasik 2017:16).

Therefore, radios and stereos have assisted listeners in achieving multi-mediated listening experiences. As Stasik notes later in his article, this contributes to the formation of different “social, sonic, and sensory” dynamics (Stasik 2017:21-24). He shows different ways music can bring Freetonians (Freetown residents) together socially through events where they can listen to music, sonically through hearing and fully experiencing music, and sonically through the reception of music and sounds as well as perceived volume.

According to this three-part framework identified by Stasik, songs like “Say It Again” clearly emerge as part of Freetown’s soundscape when played through a stereo. In the video, the stereo is switched on, and as “Say It Again” begins playing, it is included in the sounds of the city. The music accomplishes what Chosan referred to at the beginning of his video, which offers a full representation of Sierra Leonean life. The sound playing through the radio is equally as important as the sounds heard across the city. In returning to Stasik’s work, as Chosan’s music is heard throughout the neighborhood where the radio is located, it becomes part of a larger communal sound. It is not simply associated with the yard or the little boy featured at the beginning of the video.

“Say It Again” ends with a group of children dancing and listening to the song back at Chosan’s mother’s house. They all say that they will win and close with Chosan’s signature phrase – “Keep shining.” Chosan explained the significance of this phrase in a message that he sent me in January 2016: “‘Keep Shining’ is my way of saying and encouraging folks to share their inherent gifts, talents, and souls to their families and communities…” (Chosan, personal communication, January 30, 2016). Chosan shines through the music and accompanying video for “Say It Again.” They add another component to Freetown’s soundscape.

My trip to Freetown revealed the complexities of sound in the city. It helped me to forge linkages between my childhood memories, descriptions appearing in Chosan’s track “Say It Again,” as well as new experiences navigating different urban neighborhoods. Watching scenes from “Say It Again” encouraged me to return to Freetown after several decades to witness the city first hand. The video offered a glimpse of a thriving city. The accompanying soundscape successfully told a story of the communities, cultures, and people contributing to Freetown’s beauty.

References

Chosan. 2018. Personal communication with the author, October 14.

_____. 2018. Personal communication with the author, November 9.

_____. 2016. Personal communication with the author, January 30.

Feld, Steven. 2012. Jazz Cosmopolitanism in Accra: Five Musical Years in Ghana. Durham,

North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Schafer, R. Murray. 1993. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the

World. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Stasik, Michael. 2017. “How to Dance to Beethoven in Freetown.” Anthropology Matters,

17(2):11-27.

_____. 2010. Disconnections: Popular Music Audiences in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Bamenda:

Langaa Research and Publishing Common Initiative Group.

_____. 2010. “Disconnections: Popular Music Audiences in Freetown, Sierra Leone.” Research

Master’s Thesis in African Studies African Studies Centre/Leiden University.

Tucker, Boima. 2013. Musical Violence: Gangsta Rap and Politics in Sierra Leone. Uppsala:

Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

Discography

Chosan. 2021. Glareification. Silverstreetz Entertainment.

_____. 2017. Glare La Musica. Silverstreetz Entertainment.

_____. 2013. Till I Touch the Sun. Silverstreetz Entertainment.

_____. 2008. Diamond in the Dirt. Silverstreetz Entertainment.

Videography

Chosan. 2018. “Say It Again.” <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCXmVTz9nOY.>

Accessed March 1, 2018.

[1] According to Murray Schaffer, the soundscape is defined as the sounds comprising the environment (Schaffer 1993).