Kanye Goes West: The Move to Wyoming and “New Gilded Age” Conservatism

It was September of 2019 when the Sheridan Press, a small-town Wyoming newspaper, announced Kanye West’s upcoming Sunday Service at a nearby museum. In a mere instant, Wyomingites across the state did what many rural residents do in times of increased excitement: they flooded the local newspaper’s Facebook page. The post about West’s performance received the largest number of Facebook comments in the Sheridan Press page’s history (Addlesperger 2020).[1] The social media frenzy around his performances transferred into real life: as a white, rural, Montanan myself, West’s arrival was placed rather surprisingly at the center of my social media feeds. West’s ranch is just a little over an hour away from my hometown and his 2019 arrival sent shockwaves through my community. Long Facebook comments and overheard conversations in my local tractor supply praising West, his identity, and his decision to move to Wyoming seemed to follow every interaction. This level of excitement was remarkable. As a local op-ed writer, Doug Blough observed, this is not the first time that a “show business A-lister” has moved into Wyoming (Blough 2019). Harrison Ford, Sandra Bullock, Julia Louis-Dreyfuss and RuPaul Charles all own property in the state, but none of them received a social media frenzy rampant enough to rival that of Kanye West (Casper Star-Tribune 2020).[2] What made Kanye West a flashpoint for a plethora of op-eds and hundreds of Facebook comments among majority white, conservative, Wyomingites?[3]

The responses to West’s arrival in Wyoming demonstrate the cacophonous nature of shifting “New Gilded Age” conservative ideologies. West’s own political leanings are no secret, and his support for Donald Trump and failed bid for president in 2020 have made him an incredibly significant political figure (Moen 2020). This, coupled with West’s openness about his struggles with mental health and his continued forays into performance art and fashion (not to mention the long awaited release of his 2021 album Donda) have kept the performer/designer/rapper increasingly in the public eye.[4] It isn’t just the things that propelled West to the center of conversations among rural Wyomingites that make his relocation noteworthy: it is the manner in which West was discussed. West and his decision to relocate to Wyoming were explicitly being praised, and praised via a neoliberal individualistic positionality that held up West and his identity as a Black Christian male entrepreneur as emblematic of a new brand of right-wing conservatism.

Political science scholars Joseph Lowndes and Daniel HoSang have identified this form of valorization not just as a singular event, but as a cogent pattern. In their 2019 book Producers, Parasites, Patriots: Race and the New Right Wing Politics of Precarity, they argue that we must understand the new operating mode of right-wing conservatism wherein “race—whether in the form of neoliberal multiculturalism, far-right authoritarianism, or claims about cultural and genetic fitness—will continue to be pressed into service by those who wish to solidify and extend the extreme political and economic hierarchies that foster human misery and planetary destruction” (HoSang and Lowndes 2019: 168). In this piece, I rely on HoSang and Lowndes’ theory as a framework for examining Facebook comments, letters to the editor, and opinion columns from local newspapers that address West’s Wyoming performances and relocation. Applying their framework to the reactions to West’s Wyoming move and conservative turn exemplify how “New Gilded Age” right-wing conservatism has leveraged an insidious new brand of multiracial neoliberal individualism to uphold white supremacist ideologies.

The Producer

HoSang and Lowndes note that, for middle and upper-class white conservatives, being categorized as a “producer” is defined in opposition to being categorized as a “parasite.” A “parasite,” according to right-wing ideology, is a person who does not contribute economically to society and drains societal economic resources via participation in governmental social welfare programs. A “producer,” on the other hand, produces (rather than drains) economic value. While these categories have historically been racially segregated, HoSang and Lowndes note that being a “producer,” a category that has historically been reliant on and exclusively granted to whiteness, is now experiencing racial transposition onto Black bodies that reproduce neoliberal ideologies (HoSang and Lowndes 2019: 23). A letter to the editor from early fall of 2019, reflects how “New Gilded Age” conservatives apply this transposition. When it was announced that West would not only be purchasing land and performing in Wyoming, but would be moving the headquarters of his billion-dollar fashion brand, Yeezy, to the small town of Cody (Wolfson 2019a), a woman named Debbie Urick wrote the following to the Cody Enterprise:

“Kanye West and his family are welcome here as is anyone, whether they choose to live here permanently or sporadically. Their contribution to the economy, employment and tax base cannot be ignored. To deny them their God-Given Right as an American to live and work where they choose makes me question the motives of [other writers]” (Urick 2020).

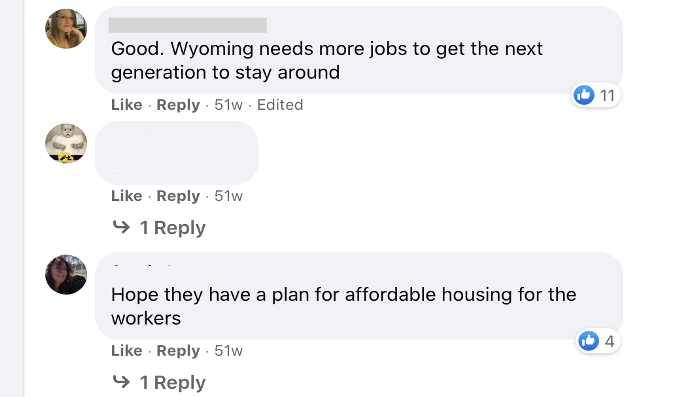

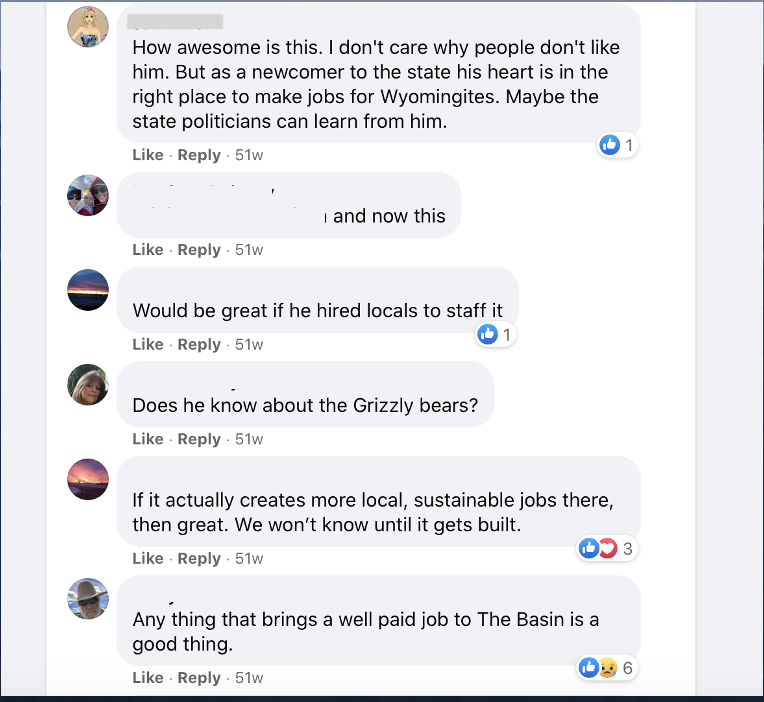

Urick was writing in direct response to an individual who suggested the West/Kardashian arrival would strip Wyoming of its “natural charms” (Kopleman 2020). Urick’s emphasis on the economic improvements West’s manufacturing could bring to the town of Cody are echoed in the Facebook comments from the Cody Enterprise post announcing the headquarters’ relocation. One commenter writes, “Good. Wyoming needs more jobs to get the next generation to stay around” (Commenter1 2019, Fig. 1) and another says, “How awesome is this. I don’t care why people don’t like him. But as a newcomer to the state his heart is in the right place to make jobs for Wyomingites” (Commenter2 2019, Fig. 2). Urick’s defense of the West’s relocation goes on to elaborate along the same tack, asking: “are they [The West/Kardashian family] racist? Are they anti-Christian? Are they anti-Trump or are they anti-economic growth for Wyoming? The Wests have the right to live here as you have the right to visit Wyoming or not” (Urick 2020).

Figure 1

Figure 2

In these comments, West is generalized as a “producer.” The perceived economic value he will bring to the region results not only in statements of welcome, but in an explicit categorization as a patriotic “American” with “God Given Rights,” whose pro-Trump, pro-Christian, and pro-economic growth stances make him the perfect candidate to live in Wyoming.[5] Yet this manner of praise is deeply troubling: it makes the right to live in a particular area contingent on one’s ability to produce economic value in addition to one’s subscription to and reflection of geographically specific dominant political ideologies. This particular mode of conditional acceptance is not new, and though discriminatory and violent, is only one portion of HoSang and Lowndes classification of “New Gilded Age” conservative strategies. Rather, it is the first question Urick asks that signals another radical shift in conservative strategy. Not only was West’s welcome contingent on assimilation to a brand of neo-liberal conservatism, but it was also contingent on the West family not being racist. The comment is just a small example of what HoSang and Lowndes note is the danger of this new form of right-wing ideology, namely that:

“Many of the conservative forces that engage and deploy the language of multiculturalism, civil rights, and Black uplift champion policies and worldviews that worsen material and social inequalities; sharpen state violence, militarism, and authoritarian governance; and make greater numbers of people vulnerable to early death” (HoSang and Lowndes 2019: 156).

The Neoliberal Individual

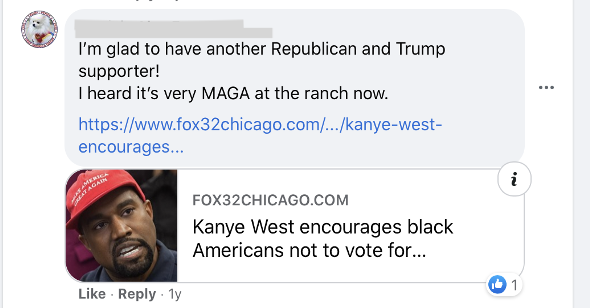

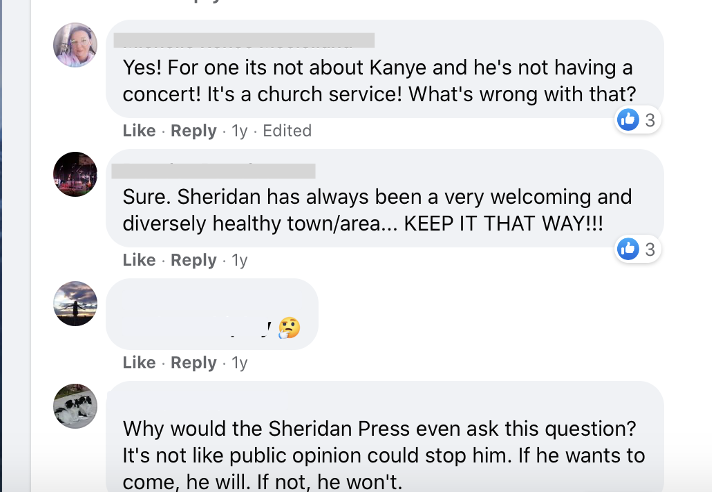

Beyond Wyoming’s borders, national conservative figureheads and news outlets have specifically latched onto West’s identity as a Black, Christian, conservative, and male entrepreneur as a model for contemporary conservative “free thinkers.” Roger Stone, former Trump ally, said in an interview with the New York Times that he “really like[s] Kanye West—I like his Christianity, and I like his rejection of identity politics” (Klein 2020). Tucker Carlson, Fox News Pundit, gave an entire evening monologue praising Kanye West’s “autonomy” and free thinking (Carlson 2019). In the monologue, he quotes West’s own words and offers commentary. At one point, he quotes one of West’s criticisms of white liberals and says, sarcastically, “Kanye is a rapper and that means he is progressive – he has to be. Those are the rules, as you know. And yet there he is, criticizing liberals” (Carlson 2019). He goes on to praise West for not falling for the trap of identity politics and for being an “autonomous” thinker who aligns with right-wing ideology. Carlson incorrectly identifies West’s statements as solidarity with conservative ideology, when in reality, West’s specific comments were engaging in the historic practice of Black artists critiquing white liberals for supporting racist policies and failing to seriously engage in struggles for civil rights. More locally, Wyoming commenters latched onto the same type of rhetoric: “I’m glad to have another republican and Trump supporter! I heard its very MAGA at the ranch now” (Commenter3 2019, Fig. 3). His specific identity as being a racialized “outsider” has also been used by locals to evidence the area’s “legendary” diversity and tolerance for newcomers, with one commenter writing “Sheridan has always been a very welcoming/diverse place. KEEP IT THAT WAY!!!” (Commenter5 2019, Fig. 4).[6] In all of these instances, West’s particular identity as a Black man and rapper who identifies himself (at least part of the time) with the hardline conservative politics of those like Donald Trump has important ramifications for “New Gilded Age” conservatism’s neoliberal claims of “diversity.”

Figure 3

Figure 4

If West’s economic value offers him the “right” to live in Wyoming, his categorization as a successful Black businessman who is free from the “identity politics” of the left positions him as the ideal “New Gilded Age” conservative man. HoSang and Lowndes write that in “New Gilded Age” conservatism, “race not only stands in as an ethical and redemptive subjectivity that works to reinforce and naturalize a host of ideas central to modern conservatism; it also symbolizes a kind of outsider status with which many white conservatives have come to identify” (HoSang and Lowndes 2019: 78). Rather than offering up Kanye West’s story simply as an exemplar of “a United States where all are welcome to participate and all are individually responsible for their achievements, as well as for their failures,” his success is heralded because of his complex racial, religious, and class identities (Kajikawa 2018). Instead of symbolizing resilience in the face of an oppressive and unequally designed system, West’s success is presented as evidence that the system is (contradictorily) both unequal and working, and thus is not in need of change. Praise of West’s success in “overcoming” being the symbolic raced “outsider” (as HoSang and Lowndes put it) is a tacit acknowledgement that the systems currently in place are designed to privilege white positionalities and uphold white supremacy. At the same time his success is being heralded publicly as proof that the system isn’t racist, and thus, as a shield against calls for abolition or reform of the system. This neat (if contradictory) logic hasn’t made room to account for what is perhaps the most important missing piece of conservative leveraging of West’s identity: his music.

Facing the Music

While the “New Gilded Age” brand of conservatism relies quite heavily on adapting multiracial coalition and applying it to uphold white supremacy, the piece of Kanye West that conservatives haven’t yet been willing to leverage is his music. Letters to the editor and comments are quick to mention West’s turn to evangelical Christianity, and if they mention his music at all, it is his newer musical turn that centers Gospel music and overtly religious themes. For example, one commenter wrote when the Sheridan Press posted about West’s Sunday Service potentially moving to other cities in Wyoming: “Yes! For one it’s not about Kanye and he’s not having a concert! It’s a church service! What’s wrong with that?” (Commenter4 2019, Fig. 4). But the distinct lack of mentions of hip hop in reactions to West’s move proves its very importance, and moreover, hip hop’s conspicuous absence points to a plethora of questions about its role in “New Gilded Age” conservatism.

Tricia Rose writes that rap lyrics are ““predominantly counterhegemonic (by that I mean that for the most part they critique current forms of social oppression)” (Rose 1994: 123). Perhaps white, rural, conservative’s refusal to latch onto hip hop as another demonstrator of “diversity” only evidences Rose’s claim that hip hop is predominantly invested in critiquing systems of oppression, and thus, is not easily leveraged toward oppressive ideologies. Perhaps hip hop, as Loren Kajikawa puts it in an article on Hamilton: An American Musical, is “so thoroughly coded as black,” that conservatives, despite their new turn towards multiracial coalition, “explicitly [break] with the neoliberal consensus that values ethnic diversity and integrated global markets” to exclude hip hop (Kajikawa 2018: 479). It begs the question: will white, rural conservatives ever leverage hip hop the same way they are beginning to leverage Kanye West’s identity as a Black entrepreneur? On the other hand, Rose also notes that rap music’s status as counterhegemonic does not “deny the ways in which many aspects of rap music support and affirm aspects of current social power inequalities” (Rose 1994: 123). Political scientist and economist Lester Spence writes about the manner in which neoliberalism is reflected in hip hop’s creation practices and reception (Spence 2011). He writes that “rap and hip-hop’s productive, circulative, and consumptive politics both mirror and reproduce what I call the neoliberal narrative across space” (Spence 2011: 11).[7] Perhaps Spence’s conclusions can be drawn even further: what does it mean if Kanye West’s music reflects not only neoliberal ideas, but actively contributes to the newly forming mode of right wing politics?

Conclusion

West’s stays at his Wyoming properties have grown longer and more frequent since I first started writing this piece last year. Indeed, he’s nearly relocated to Wyoming on a permanent basis. And yet, even after all this time, his Wyoming reception has left me with far more questions than answers. What does West’s move to Wyoming and his potential replication of conservative logics via his music mean for the ways hip hop can be politically leveraged? What types of nuanced conversations are necessary to confront West’s music? How does West’s move to Wyoming interact with settler colonial logics and the legacy of conquest in the American West? To quote hip hop feminist Joan Morgan, the “grays” in this situation are abundant (Morgan 1999). The primary source research into Facebook comments and letters to the editor I’ve collected here demand further, deeper theorization. Questions of mental health, celebrity, and the changing landscapes of West’s music certainly come to bear on his reception in conservative locales. While it might be simpler – and perhaps less painful – to explain away Kanye West’s politics as a product of personal political idiosyncrasy and separate it from his art, we, as music scholars, are charged to wade through the complexities and contradictions played by music in a “New Gilded Age” conservatism that is able to leverage multiracial coalition to gain support for white supremacist policies and actions.

Notes

[1] For more on the West’s arrival in Cody, see Dough Blough, “Wests Are Soon Coming to the West.” Cody Enterprise, September 11, 2020. https://www.codyenterprise.com/news/opinion/article_39e093ca-d4c7-11e9-9190-7b84680389c8.html.

[2] For discussions of RuPaul Charles’s property in the state see, Cassidy Randall, “Rumors of RuPaul’s Fracking Ranch May Be Surprising to Some – but Not His Wyoming Neighbors.” The Guardian, August 28, 2020, sec. Environment. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/aug/28/fracking-wyoming-ranchers-rupaul (accessed 10-14-2021) For more on other celebrities who live in or have connections to Wyoming, see the Casper Star-Tribune, “Meet 33 Famous People with Wyoming Connections,” Casper Star-Tribune. October 16, 2019. https://trib.com/news/local/casper/meet-33-famous-people-with-wyoming-connections/collection_8bf6045d-fcfa-518e-85eb-cfefda0beb56.html (accessed 10-14-2021).

[3] For more on Wyoming’s demographics see United States Census Bureau. 2019. Quick Facts: Wyoming. Distributed by the United States Census Bureau. 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/WY (accessed 10-10-2021). For more on Wyoming’s political makeup, see Politico, “2020 Wyoming Results.” Politico, January 6, 2021, https://www.politico.com/2020-election/results/wyoming/ (accessed 10-14-2021).

[4] For more information and recent scholarship on West’s cultural and societal impact, see The Journal of Hip Hop Studies special issue: Joshua K. Wright, VaNatta S. Ford, and Adria Y. Goldman, 2019. Special Issue: “I Gotta Testify: Kanye West, Hip Hop, and the Church,” Journal of Hip Hop Studies (6):1. For more on West’s mental health struggles, check out this Teen Vogue piece: Prior, Harriet. 2021. “As a Person With Mental Health Struggles, Kim and Kanye Made Me Feel Seen.” Teen Vogue. January 7, 2021. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/kim-kardashian-kanye-west-divorce-mental-health (accessed 10-15-2021).

[5]Though the Facebook comments made were welcoming, I do not mean to suggest that these commenters would, in fact, always be welcoming. As I write a bit later in this piece, there are dual narratives running through several small towns in the Western U.S., simultaneously construes the town and its majority white occupants as “welcoming”, while in practice those residents can actively sponsor white supremacist, racist policies and perpetrate acts of interpersonal racism.

[6] Sheridan is located on the territory of the Apsaalooké, Cheyenne, and Očhéthi Šakówiŋ peoples, as are West’s two ranches. The settlement of Sheridan was violent, and the town was founded as a military fort during the U.S. Cavalry’s attempt to seize land from the alliance of Lakota, Cheyenne, Očhéthi Šakówiŋ peoples. For more details on the colonization of the area and of Sheridan, specifically see Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, 2014. An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press; Philip H. Sheridan, 1882. Report, Dated Sept. 20, 1881, of His Expedition through the Big Horn Mountains, Yellowstone National Park, Etc. Washington: Government Printing Office.

References

Addlesperger, Caitlin. 2019. “Wyoming’s Kanye-Phobia.” The Sheridan Press, September 27, 2019. https://www.thesheridanpress.com/opinion/columnists/wyoming-s-kanye-phobia/article_f1eef43a-d33f-507c-b495-b636a33dade1.html.

Bailey, Julius. 2014. The Cultural Impact of Kanye West. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Blough, Doug. 2020. “Wests Are Soon Coming to the West.” Cody Enterprise, September 11, 2020. https://www.codyenterprise.com/news/opinion/article_39e093ca-d4c7-11e9-9190-7b84680389c8.html.

Carlson, Tucker. 2019. “Tucker Carlson: Kanye West vs the Mob – Rapper Declares Independence from Guilty Self-Righteous Liberals.” Fox News, October 31, 2019. https://www.foxnews.com/opinion/tucker-carlson-kanye-west-liberals.

Casper Star-Tribune. “Meet 33 Famous People with Wyoming Connections,” October 16, 2019. https://trib.com/news/local/casper/meet-33-famous-people-with-wyoming-connections/collection_8bf6045d-fcfa-518e-85eb-cfefda0beb56.html.

HoSang, Daniel Martinez, and Joseph Lowndes. 2019. Producers, Parasites, Patriots: Race and the New Right-Wing Politics of Precarity. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvdjrrcq.

Kajikawa, Loren. 2018. “‘Young, Scrappy, and Hungry’: Hamilton, Hip Hop, and Race.” American Music 36 (4): 467–86. https://doi.org/10.5406/americanmusic.36.4.0467.

Klein, Charlotte. 2020. “‘I Really Like Kanye West’: Republicans Bank on a Spoiler Candidate to Save Trump.” Vanity Fair, August 5, 2020. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2020/08/i-really-like-kanye-west-republicans-bank-on-spoiler-candidate-to-save-trump.

Kopelman, Sami Long. 2020. “Letter: Kanye West Hurts Allure of Wyoming Visit.” Cody Enterprise. January 1, 2020. https://www.codyenterprise.com/news/opinion/article_cc8a540e-2bfc-11ea-bae8-efabf341e0a4.html.

Moen, Matt. 2020. “Kanye’s Back on His Bullsh*t.” PAPER, July 8, 2020. https://www.papermag.com/kanye-west-president-2646359752.html.

Morgan, Joan. 1999. When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: A Hip-Hop Feminist Breaks it Down. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Politico, “2020 Wyoming Results.” Politico, January 6, 2021, https://www.politico.com/2020-election/results/wyoming/. [accessed 5-10-21].

Randall, Cassidy. 2020. “Rumors of RuPaul’s Fracking Ranch May Be Surprising to Some – but Not His Wyoming Neighbors.” The Guardian, August 28, 2020, sec. Environment. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/aug/28/fracking-wyoming-ranchers-rupaul.

Rose, Tricia. 1994. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Music/Culture. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press.

Spence, Lester K. 2011. Stare in the Darkness: The Limits of Hip-Hop and Black Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wolfson, Leo. 2019a. “Kanye West Holding Sunday Service in Cody.” Cody Enterprise, September 20, 2019. https://www.codyenterprise.com/news/local/article_ac482572-dbfc-11e9-9d84-2385a15d30d2.html.

———. 2019b. “Kanye West Moving Yeezy Headquarters to Cody.” Cody Enterprise, November 8, 2019. http://www.codyenterprise.com/news/local/article_6199c69e-0284-11ea-a164-7335447ec6e5.html.

United States Census Bureau. 2019. Quick Facts: Wyoming. Distributed by the United States Census Bureau. 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/WY.

Urick, Debbie. “LETTER: Kanye West and Family Are Welcome Here.” Cody Enterprise, January 6, 2020. https://www.codyenterprise.com/news/opinion/article_14e8c818-30bf-11ea-a8a7-7729c4485afa.html.

Wright, Joshua K, VaNatta S. Ford, and Adria Y. Goldman, 2019. Special Issue: “I Gotta Testify: Kanye West, Hip Hop, and the Church,” Journal of Hip Hop Studies (6):1.

Facebook Comments

Commenter1. Comment re: The Cody Enterprise. “Kanye West announced on Thursday he will be moving headquarters for his Yeezy fashion line to Cody.” Facebook, November 8, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/CodyEnterprise/posts/10157848860208104.

Commenter2. Comment re: The Cody Enterprise. “Kanye West announced on Thursday he will be moving headquarters for his Yeezy fashion line to Cody.” Facebook, November 8, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/CodyEnterprise/posts/10157848860208104.

Commenter3. Comment re: The Cody Enterprise. “Kanye West announced on Thursday he will be moving headquarters for his Yeezy fashion line to Cody.” Facebook, November 8, 2019. https://www.facebook.com/CodyEnterprise/posts/10157848860208104.

Commenter4. Comment re: The Sheridan Press. “Should Kanye Come to Sheridan?” Facebook, September 24, 2019.

Commenter5. Comment re: The Sheridan Press. “Should Kanye Come to Sheridan?” Facebook, September 24, 2019.

BIO

Siriana is a third year PhD student whose research focuses on intersectional feminist critique of musicking throughout the American West. Her dissertation centers on the structures of power that surround musicking in the red-light districts of Rocky Mountain mining towns. Siriana is also dedicated to public scholarship and has curated digital exhibits on the life and legacy of Dr. Eileen Southern and race and gender in the American West. She holds a B.M. in Vocal Performance and Gender Studies from St. Olaf College, which mostly means that she just loves to sing. But, when she’s not singing, she can likely be found watching Star Trek.