Lost in the World(s): Bon Iver, Kanye West, and Generic Environmentalisms

A Tale of Two Artists

The reception of Bon Iver is a tale of sequestration in Justin Vernon’s native rural Wisconsin. The result of Vernon’s isolation was For Emma, Forever Ago, a stunning 2008 debut album comprised of cryptic narratives accompanied by twinkling guitars and reverberant echoes. The albums released in the decade since have only strengthened the discourse steeping his work in human-nonhuman relationality. Critic Sasha Frere-Jones highlights how Vernon’s story typifies the narrative that many indie artists rely on for bolstering their capital (Frere-Jones 2009). Despite the ubiquity of this tale, however, Vernon asserts that what he sees as demos can stand without extramusical context: “I think the story pulls people into the music… But I hope people are reacting to the music [itself]” (Vernon 2008). Bon Iver’s origin story has circulated to take on a life of its own, and the signatory acoustic textures are now supplemented with autotuning, electronic distortions, and sampling. With these sonic shifts, today’s Bon Iver refashions indie folk by deploying sounds of urban modernity, even as Vernon remains committed to indie folk’s transcendentalist-inflected environmentalism. Bon Iver promotes a rethinking of what is gained through these changes in the “authentic” indie folk sound.

And yet there is another story of isolation to be told. In 2019, Kanye West purchased a pair of multimillion dollar ranches in the Rocky Mountain West. Preceding the purchase, West recorded his album Ye (2018) in Jackson Hole, WY and flew in celebrity friends for its launch. Since his rise, Kanye has maintained traces of an outsider status as a hip hop artist, largely because of his upbringing as a middle-class Black American without the street-based image typical of many hip hoppers. As Regina Bradley points out, West’s rather cosmopolitan sound “reflects a worldly outlook while remaining attached to the proverbial hip-hop block” (Bradley 2014). Further, after interrupting Taylor Swift at the 2009 VMAs, West has consistently defended himself as a victim of cancel culture because of his voicing of systemic denials of African-American contributions to popular music (Cullen 2016). Despite his self-proclaimed status as arbiter of (Black) culture, his westward move extends an outlaw narrative that feeds into the privilege akin to indie’s isolationism.

Vernon and West’s stories collide during the 2010s, when Vernon’s voice appears on West’s 2010 album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. This moment marks the beginning of Bon Iver’s shift to a sound-world marked by hip hop-like practices partially inspired through this collaboration with West. What follows in this essay explores some of the environmental-spatial values constituted by the two artists and their respective genres through their collaboration. I also sit with West-ian traces in later Bon Iver projects and the environmental narratives surrounding their discography. Through this insertion into indie environmentalism, West furthers his propensity towards transgressive boundary-crossing central to his music-making, entrepreneurship, and identity display. I frame the track “Lost in the World” as a confrontation between hip hop as an urban genre and indie folk as a “natural” genre. These spatial interventions have only gained relevance with West’s forays into the Rocky Mountain West and broadcasts of Sunday Services in nonhuman, “natural” built locales. Because this collaborative relationship constitutes an inflection point, I conclude by gesturing towards how Bon Iver is taken up by recent hip hop artists as some have embraced a seemingly more intimate expressivity. By sitting at generic boundaries, this paper addresses how hip-hop voices “the tensions and contradictions in the public urban landscape…and attempts to seize the shifting urban terrain” (Rose 1994). This emerges in Bon Iver’s borrowing from the genre to push his already pastiche-y style into another sound world, and also emerges in Bon Iver’s sound used to evoke alternative spaces and temporalities. This analysis at the coming-together of these materials frames this music as able to chip away at the monolith of whitewashed legacies of U.S. environmentalisms.

Genres in Space

My naming of indie folk as a natural genre relates to legacies with environmental protest folk of the mid-twentieth century. Bon Iver’s practice exemplifies the folk-like ethos of embracing a narrative, confessional tone that deploys non-linear and barely-sensical storytelling to reframe time and space. This tendency to rearrange temporo-spatial relations pervades tropes of indie isolationism. Signaled by terminologies like “cabin in the woods” or “middle of nowhere,” this narrative frequently describes the generative process and refers to the quality of the musical sounds, as well (DelCiampo 2018). This dissociation from geographic place keys into indie’s particular attraction to “[supplying] a space in which artworks seem to exist outside the condition of their production” (Hibbett 2005). This kind of ambivalence also attests to indie’s reification of the racial, class, and gender homogeneities of their artists and audiences (i.e. white, middle-class males). Invoking a middle of nowhere, then, is worn as a badge of pride for practitioner; and pursuing enhanced creativity via willful movement mimics desires to appear as an understated cultural product that embraces privileges associated with a more elite middle-class.

Because indie folk musicians manipulate the boundaries of where its musicking occurs, indie has been argued to “[exist]… as a nebulous ‘other,’ or as a negative value that acquires meaning from what it opposes” (Hibbett 2005). The refusal of placedness is an ambivalence, especially considering its tensions with a United States-ian conforming to Transcendentalist ideas of Americanness. The following Pitchfork review of Bon Iver’s sophomore album drives this point home:

“The song titles [on Bon Iver’s sophomore album, Bon Iver] reference actual places (“Calgary”) and places that sound real, but aren’t (“Hinnom, TX”, “Michicant”); they’re less about geography and more about putting a name to a state of mind that mixes clarity and surrealism” (Richardson 2011)

Richardson writes that the album’s bright arrangements convey a protagonist’s series of intoxicated, musicalized real and imagined places. By asserting that the album “[puts] a name to a state of mind,” Richardson highlights the evasiveness of physical place. With Bon Iver as a poster child, indie’s transience amongst existing regions, invented places, and placeless-ness displays its operation in a non-place, a term describing a mode of being “geographically situated within a place [that] bears little resemblance to that place” (DelCiampo 2018). Deeming indie folk as “natural” thus refers to the nature-themed content and its naturalizing of certain geographic and environmental experiences.

Though, as a musical culture originating in Black communities pushed to societal margins, hip hop emerged in a different kind of non-place. 2020’s anti-racist protests have unveiled how the encroachment of grey-space upon greenspaces disproportionately affects communities of color. This impacts the defense and protection of public space, which then shapes people’s interactions (Kelley 1997). Gaye Theresa Johnson’s notion of spatial entitlements similarly asserts the meaningfulness of space “for the survival of communities, but also for the discursive practices encoding the stories that define and redefine who people are” (2013). Even as environmental reshapings have long constrained Black and Brown movements, struggles over spatial entitlements do enable the production of new forms of sonic relations. Perhaps the fullest contribution to this area of inquiry is Murray Forman’s The ‘Hood Comes First, which asserts the urban sphere as hip hop’s frame of reference, wherein techniques of flow, layer, and rupture transform narratives of spatialized power into musico-sonic production (Rose 1994). As Forman puts it, the reiterative processes, recurrent practices, and repeating narratives encompass “the overlapping duality of habitation and habituation” wherein apprehensions of space produce differentiations of place “according to rhythms of movement and patterns of use” (2002).

These spatializations demonstrate that spaced-ness and placedness lurk behind the formation of popular music genres. This might be unsurprising since music “is a place of sorts, replete with its own metaphorical locations, types of motions, departures, arrivals, and returns” (Watkins 2011). Figuring music as place fosters additional understandings of musical artifacts and materials as unstable interactive sites, which seems particularly generative for considering the environmentalisms emerging in sites of musical encounter. If genres should be considered “dynamic ensembles[s] of correlations,” their dynamism means that groupings are continually enacted and reenacted, which facilitates awareness of a genre’s instantiation through its transgressing or juxtaposing of boundaries (Drott 2013). Bringing indie folk and hip hop’s environmental values in conversation thus unveils a new musical place of sorts.

From Woods to World

“Woods” marks Bon Iver’s initial shift from a typical indie sound. Expanding and eschewing the typical instrumentations and textures associated with indie or alternative rock, “Woods” signals a new chapter in Bon Iverian techniques (Navarra Varnado 2019). With Vernon’s auto-tuned and layered voice as the sole instrument, the song repeats a single stanza of text. Each repetition layers vocalizations into a digital choir comprised of choral subsets each with their own timbres. The first five repetitions demonstrate Vernon’s additive treatment of material, most easily heard through the addition of one part per repetition, culminating in five-part homophony. After 2:00 minutes, the additive process becomes decreasingly predictable, more polyphonic, and more timbrally expansive. With each interjection, the intensifying volume and variety fosters a sense of increasing desperation, as if each musical exclamation is a stronger plea for the sought-after clarity of being “up in the woods.” Vernon builds a “woods” (rather than a mirrored representation of the physical woodlands that inspired the song), thus making the song emblematic of the isolationist narrative that dually embraces the reality of nonhuman nature and its musically reconstructed counterpart.

Obvious manipulations of voice remain among the most contested techniques in popular music (Brøvig-Hanssen and Danielsen 2016). T-Pain is most often credited for moving autotuning away from mere pitch correction towards a chosen aesthetic expressiveness beyond human-given abilities, since taken up by countless other hip hop and R&B artists in the intervening years. Especially following Kanye West’s 808s and Heartbreaks, digital vocal corrections have come to be connoted with alienation or loss, which holds true for “Woods.” Further, around this time, Joseph Auner indicates that “the unaltered human voice [had] become an endangered species.” Vernon’s pitch correction and close-microphoning render the content more intimately authentic through their heightening of his individuality (Auner 2003). But this authenticity conflicts with expectations about unfiltered human vocalization, and this tension supports hearing “Woods” as a disoriented, despairing inner monologue.

Though, one might resist understanding the digital choir as the deep interior of the protagonist sitting within the song’s geographic setting. This nonhuman singing registers as distanced or alienated because of its sonic dissociation from the human source of its creation. “There is something utterly hypernatural” about these voices because “we hear [Vernon’s] robotic, alienated alter ego” express the feeling of being “up in the woods” (Brøvig-Hanssen and Danielsen 2016). The natural-ness points to the image of a crisp winter landscape of white perfection that one draws upon for growing attuned to an inner self. And the glitchy autotuning, echoes, and piercing interjections musically convey this coldness. But the “hyper” points to the song’s reframing of woodlands and speaks to the digital choir as dissociated from its human source. Bon Iver has created a virtual reality, a term defined by environmental historian Bill Cronon as a testament to modern alienations from nature (Cronon 1996). Vernon’s voice treated with what has become a naturalized technique is the substance of this human-nonhuman musical assemblage. The extra-musical narrative about Bon Iver’s collaboration with nonhuman nature strengthens the durability of his origin story.

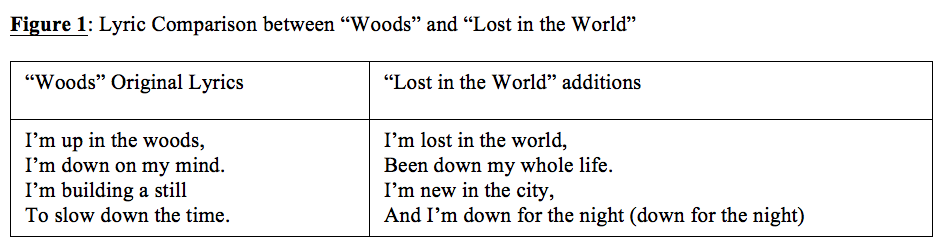

“Woods” is the centerpiece of “Lost in the World” on Kanye West’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy (2010). The opening features three repetitions of “Woods,” all of which differ in tempo and are one whole step higher than the original. At around 1:00 minute, West’s autotuned voice enters with vibrant percussion, piano, and an energetic bassline. At this moment, West overlays his own lyrics to produce a homonymous doubled effect atop Vernon’s original, shown in Figure 1 below.

Just as “Woods” captures the feeling of loneliness, “Lost in the World” dons similar cloth. In the song’s singular extensive verse, West craves purer experiences, saying: “Lost in this plastic life / Let’s break out of this fake-ass party / turn this into a classic night.” Unlike Vernon’s reprieve in the solace of rurality, West’s lyrics critique the artificiality of urban life even while searching for reprieve in its essential quality of urban-ness. West’s audible pitch-correction refashions his voice into a lead vocal, which creates “a dynamic musical expression that encourages immediacy between artist and listener” (Burns, Woods, and Lafrance 2016). Here, a blurring between rapper and singer establishes an assemblage not unlike Bon Iver’s woodedness.

The sound-world of “Lost in the World” signals the same ambivalence about city living, as the song transcends expectations of urban hip hop by overlapping the percussion with a sea of echoes from Vernon and gospel-like background vocals. Kanye’s enmeshment with “Woods” can also be heard as a critique of white male eco-aesthetics, in that his lyrical changes reflect differing generic conventions related to the racial-class relationships to natural space, as described in the preceding section. The song also reflects West’s self-positioning as unbeholden to expectations, since his self-positioning involves displacement at the level of genre, class, and location. “Woods” and “Lost in the World” both descend into a polyvocal polyphony: in Vernon’s case, a collision amongst members of the digital choir; and in West’s case, intensified percussion thematizing an anthemic version of escape. For both artists, though, voice manipulation has become second nature, inextricable from their respective sounds throughout the 2010s.

“Just” Places?

Which brings us back to Bon Iver.

2016’s 22, A Million appeared after a five-year hiatus preceded by multiple international arena tours and several Grammy nominations (and wins). Much like 808s and Heartbreaks embraced a “sad machine” aesthetic, 22, A Million emerges from the anxious experience of a pressurized rise to fame. “It’s an attempt at a new language,” writes Hua Hsu (2016) with what Elizabeth Navarra Varnado calls an “uncanny, unnatural, or even overemotional” sound (2019). In the song “33 “GOD””, Vernon sings “these will just be places to me now,” which signals an intentional move away from the place-based associations that defined previous output. Glancing at the track listing pictured below (Figure 2) reveals how the album melds philosophy, religion, and mathematics to invite nonhuman and non-Earthly perspectives of space.

Figure 2: Tracklist of Bon Iver's album 22, A Million (2016)

“33 “GOD”” is also microcosmic of Bon Iver’s application of hip hoppy techniques of flow, layer, and rupture. The song juxtaposes samples autosonically. Rather than presenting performative quotations dragged from one context and dropped into another, the samples from Paolo Nutini, The Isley Brothers, Jim Ed Brown, and others have been manipulated to match the timbre and tonality of Vernon’s voice (Navarra Varnado 2019). As a result, the song maintains a continuous emotional tone even as the materiality of the sounds break from Vernon’s earlier sonic expressions and as the crunchiness throughout is onomatopoeic of rupture. Vernon’s flow allows for a self-effacement since his voice falls into a choir of other voices and voice-like instrumentations. Though, Bon Iver’s self-effacement conflicts with the fact that this effacement has always been signatory to his musical language.

Bon Iver’s influence can be heard in other hip hop contexts today, as in the case of an interpolation on the song “Distant” (2018) by Jaden (Smith) or in an extensive sample heard on Chance the Rapper’s “Summer Friends” (2016) that was later released as its own song. In both cases, Vernon’s sound and vocalizations lend an ethereal otherworldliness that Jaden and Chance use to evoke a personal and musical sense of nostalgic longing. This seems to be part of a move in hip hop musicianship that can be heard as an intimate turn in lyrical and sonic content that differs from and challenges monolithic assertions of hip hop as hypermasculine, aggressive, and lacking emotional sensitivity.

I hope to eventually consider how the uptake of a non-traditional environmental locale and sound (at least for hip hop genres) opens space to draw out themes coded as more intimate, and in ways that simultaneously reify and undo some of exclusionary associations with the nonhuman natural world that white-dominated genres enact. More directly to Bon Iver’s role in these shifts, the appeal of Vernon presumably reflects how his collaborations with Kanye lent him industry cred, and his crossover engagement reveals how practitioners of a genre work to determine their own boundaries, along with who and what can intervene. The compelling nature of both Bon Iver and Kanye West involves untangling what each lends to their intersecting contexts, an omnivorous approach that indeed aligns the two artists and their musicking. As Joseph Schloss writes, “the boundary between hip-hop insiders and outsiders can be rather porous,” and he refers to hip hop’s emergence in places that created new formal possibilities from diverse materials (2004). Kanye’s effect on Bon Iverian aesthetics demonstrates how an indie folk nature aesthetic in hip hop’s sounding of urban space questions ontologies of the natural, urban and unnatural. By understanding how distinctions amongst places, spaces, and their ideologies musically co-constitute each other, “nature” becomes not nearly as natural as we think.

References

Attali, Jacques. 1985. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Theory and History of Literature v. 16. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Auner, Joseph. 2003. “‘Sing It for Me’: Posthuman Ventriloquism in Recent Popular Music.” Journal of the Royal Music Association 123: 98–122.

BBC Radio 1. 2016. Kanye West Talks to Annie Mac, on Pablo, Ikea, Glastonbury and Running for President. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pbtd27tJqXs (accessed July 10, 2021).

Brøvig-Hanssen, Ragnhild, and Anne Danielsen. 2016. “Autotuned Voices: Alienation and ‘Brokenhearted Androids’.” In Digital Signatures: The Impact of Digitization on Popular Music Sound, 117–32. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Burns, Lori, Alyssa Woods, and Marc Lafrance. 2016. “Sampling and Storytelling: Kanye West’s Vocal and Sonic Narratives.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Singer-Songwriter, 159–70. Cambridge Companions to Music. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cronon, William. 1996. Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature. Pbk. ed. New York: W.W. Norton.

Cullen, Shaun. 2016. “The Innocent and the Runaway: Kanye West, Taylor Swift, and the Cultural Politics of Racial Melodrama.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 28, no. 1: 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpms.12160.

DelCiampo, Matthew. 2019. “Recorded in a Cabin in the Woods: Place, Publicity, and the Isolationist Narrative of Indie Music.” MUSICultures 46, no. 2.

Drott, Eric. 2013. “The End(s) of Genre.” Journal of Music Theory 57, no. 1: 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-2017097.

Frere-Jones, Sasha. 2009. “INTO THE WOODS: Pop Music,” The New Yorker; New York.

Hibbett, Ryan. 2005. “What Is Indie Rock?” Popular Music and Society 28, no. 1: 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300776042000300972.

Hsu, Hua. 2016. “Bon Iver’s New Voice.” The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/03/bon-ivers-new-voice.

Johnson, Gaye Theresa. 2013. Spaces of Conflict, Sounds of Solidarity: Music, Race, and Spatial Entitlement in Los Angeles. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kelley, Robin D. G. 1997. Yo’ Mama’s Disfunktional!: Fighting the Culture Wars in Urban America. Boston: Beacon Press.

Lowe, Zane, and Bon Iver. 2019. Bon Iver and Zane Lowe ‘i,i’ Interview - YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hGFndAXtnro.

Navarra Varnado, Elizabeth. 2019. “The Sampling Aesthetic of Bon Iver’s “33 ‘God.” In Proceedings of the 12th Art of Record Production Conference: Mono: Stereo: Multi, edited by J.O. Gullö, 303–18. Stockholm: Royal College of Music: KMH. http://kmh.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1320472/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

Richardson, Mark. 2011. “Bon Iver: Bon Iver.” Pitchfork. https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/15551-bon-iver/.

Rose, Tricia. 1994. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Music/Culture. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press : Published by University Press of New England.

Schloss, Joseph Glenn. 2004. Making Beats: The Art of Sample-Based Hip-Hop. Music/Culture. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press.

Watkins, Holly. 2011. “Musical Ecologies of Place and Placelessness.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 64, no. 2: 404–8. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2011.64.2.404.

BIO

Cana (KAY-nuh) is a PhD candidate in Historical Musicology at Harvard University. An Atlanta native, she earned her BA in Music and French from Emory University in 2019. There, she completed thesis work about the song cycles of composer Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) in the context of linguistic nationalist politics in France and Belgium. Currently, her work revolves around musical engagements with natural science, climate change, and environmentalisms in a variety of repertoires. Her dissertation will focus on spectrums of silence and identities rendered audible across a range of plant care practices in greenhouses, botanical gardens, and the home. Apart from her academic life, she also enjoys choral singing, running, and writing short stories.