Obrigada, Shukran: Brazilian Musical Encounters in Lebanon

Introduction

In Lebanon, and in Beirut particularly, Brazilian music and dance is practised, performed and listened to in diverse and multiple settings, from Brazilian zafeh entertainment at flamboyant Lebanese weddings, to energetic performances of música popular brasileira (MPB) in small, independent music venues. Bossa nova emanates from jazz clubs, and the Bahian carnival sounds of Bloco Rubra Rosa entertain festival crowds. Other manifestations of Brazilian music and culture in Lebanon include the growing popularity of samba dance and capoeira classes, and the humanitarian use of the latter as a therapeutic activity for Syrian refugees living in camps.

In this article, I will give a brief overview of how the presence of Brazilian music and dance in Lebanon can broadly be attributed to three interlinked factors. Firstly, Lebanon and Brazil share a long history of migration and cultural exchange, and bountiful financial remittances from the Lebanese diaspora in Brazil have helped to ensure Brazil’s positive reputation in Lebanon. Secondly, the country’s best-loved singer, Fairouz, and her son Ziad Rahbani, recorded and arranged multiple cover versions of classic bossa nova tracks by the likes of Antônio Carlos Jobim and Luiz Bonfã; a mimetic process that has resulted in a distinctly Lebanese style of bossa nova (Toynbee & Dueck 2011:10). Thirdly, the global spread and commodification of primarily Rio de Janeiro-centric Brazilian dance and music genres, notably samba and bossa nova, has also reached Lebanon. These processes have resulted in the reification of exoticist stereotypes of Brazilian culture, and the widespread practice of auto-exoticisation by Brazilian performers; a phenomenon that has been well-documented in regard to other contexts (Gibson 2013; Pravaz 2011). The demand from the cosmopolitan Lebanese middle and upper classes for varied and novel forms of entertainment is reflected in the wide variety of international restaurants, themed bars and live performances present in Beirut and across the country, and thus the prevalence of Brazilian cultural practices in Beirut is also symptomatic of Lebanon’s increasingly cosmopolitan, neoliberal modernity.

Figure 1: Bloco Rubra Rosa at the Brazil-Lebanon Cultural Centre

Migration and Remigration

Although geographically far apart, and often perceived as culturally opposite, Lebanon and Brazil share a long and rich history of migration and cultural exchange. The first significant groups of Arab migrants left for the Americas from Ottoman Greater Syria—present-day Lebanon and Syria—in the 1880s (Lesser 2013), and by 1933, the total number of Lebanese migrants in Brazil reached around 130,000 (Truzzi 1997:13; Lesser 2013:130). Lebanese migration to Brazil continued throughout the twentieth century, and Brazil became home to the highest number of citizens of Lebanese descent residing outside Lebanon. Today, the number of Brazilian citizens with Lebanese heritage is estimated at between seven and ten million.[1]

Patterns of migration and remigration between the two countries have also resulted in thousands of Brazilian citizens living in Lebanon. Thiago Oliveira, Head of Culture and Education at the Embassy of Brazil in Beirut, estimates the total number of Brazilians, meaning Brazilian passport holders, living in Lebanon at 17,000.[2] Of these, a significant proportion are Lebanese Brazilians: Brazilian-born descendants of the original Lebanese migrants.[3] These dual-heritage citizens are often known colloquially as ‘Brasilibanêses.’ Others are Lebanese citizens who left for Brazil during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), obtained a Brazilian passport, and then returned to Lebanon the 1990s. Some are Brazilian women who met and married Lebanese men in Brazil, and moved to Lebanon after their marriage. Others still are Brazilians with some Lebanese heritage, who moved to Lebanon for work, an adventure, an interest in Lebanese culture, or a better security situation.

Brazilians live all over Lebanon, although there are larger populations concentrated in particular areas. For example, in the Bekaa Valley in the east of the country, there are villages where up to 90% of the inhabitants speak Portuguese. The distinctive red-roofed houses were built with financial remittances from the Lebanese diaspora in Brazil, and the local shops have names such as ‘Copacabana Mercado’, and sell Brazilian snacks and drinks like pão de queijo and Guaraná.[4] Interestingly, despite the strong Brazilian presence in the Bekaa, there is little live Brazilian music to be found. This is partly due to its rural, remote location far from Beirut, and partly due to its social conservatism. Most of the residents of these villages are Brazilian-born descendants of the original Lebanese migrants, and the majority are Sunni Muslims.

Figure 2: Street sign in Kamed Il Laouz, Bekaa Valley

Fairouz, Ziad Rahbani and Lebanese Bossa Nova

Over the course of the twentieth century, a few prominent Lebanese musicians visited or lived in Brazil, including Wadih al Safi, who lived in Brazil for four years, and Najib Hankash, who moved to Brazil aged 18 and stayed there for several decades. The legendary singer Fairouz undertook several South American tours, including dates in Brazil in 1961, 1970 and 1981, performing to a rapturous crowd of Lebanese expatriates.[5] However, Brazilian-influenced music only first entered the Lebanese mainstream in the late 1970s, via the musical plays and albums of Fairouz’s son, Ziad Rahbani, one of Lebanon’s best-known and popular musicians and composers. Often referred to simply as Ziad, he is well known for his outspoken, and often controversial, political views, and for his innovative musical style. His early solo material was marked by experimentation with jazz harmonies, complex arrangements and musical influences from a range of international genres.

At some point in his youth, Ziad heard and fell in love with the music of Brazilian bossa nova pioneers João Gilberto and Antônio Carlos Jobim. A clear bossa nova influence, in terms of rhythm, instrumentation and melody, can be heard on his solo albums, musical theatre productions and arrangements he produced for his mother and from the late 1970s to the present day. For example, the main theme of one of his most famous and successful plays, Bennesbeh la Bukra shu? (What About Tomorrow?) (1978) is a clear example of this. The main theme, simply titled “Intro Instrumental 1,” or “First Musical Scene,” is clearly indebted to bossa nova. The opening flute melody that recurs in various guises throughout the soundtrack is highly reminiscent of the introductory flute melody of Jobim’s “Corcovado,”[6] and the drum kit and the guitar “comping” patterns adhere to typical bossa nova conventions of the 1960s. The lush instrumental arrangements are reminiscent of early Jobim: the genre conventions that Ziad favoured were popularised on such classic albums as João Gilberto and Stan Getz’s 1964 collaboration Getz/Gilberto, and Jobim’s The Wonderful World of Antônio Carlos Jobim (1965).[7]

Ziad Rahbani—“Intro Instrumental 1”

Later on in his career, Ziad also arranged classic bossa nova compositions for his mother Fairouz to sing, with Arabic translations of the original Portuguese lyrics. An example of this is his arrangement of Luiz Bonfã’s “Manhã de Carnaval" (1959) for Fairouz’s 2002 album Wala Kif.[8] Ziad maintained the original melody, but rewrote the lyrics in Arabic, naming it “Shu Bkhaf” (“How I Fear”), and completely changed the meaning of the song, from a romantic and wistful tale of the first morning of carnival, to a paranoid narration of sleepless nights and lost love. Although on first listen the song appears to follow bossa conventions, the rhythmic characteristics of bossa nova are significantly altered. Ziad only uses one ‘side’ of the bossa clave, effectively simplifying the rhythmic structure of the piece, and the melody is sung with much less syncopation than the Brazilian version.[9]

Fairouz—“Shu Bkhaf”

The Lebanese bossa nova style became so popular, and so clearly associated with Fairouz and Ziad Rahbani, that “Shu Bkhaf” has become a Fairouz classic in its own right. It has spawned its own cover versions across the Arab world, and like many of Fairouz’s arrangements of pre-existing music, the original has remained widely unknown in Lebanon, and the song became ‘hers.’[10] However, despite Ziad’s sustained engagement with Brazilian bossa nova for over forty years, he is not particularly well-known within the Brazilian community in Lebanon—aside from professional musicians. I spoke to several Brazilians living in Lebanon who were surprised to hear that he covered music by Brazilian artists, possibly because he hasn’t branched out much further than canonical bossa nova repertoire. Likewise, some Lebanese fans of Ziad I spoke to did not know that the songs and plays they loved were either cover versions of Brazilian classics, or were composed in a bossa nova style.

However, Ziad has played, and continues to play, a significant role in the promotion of Brazilian music in Lebanon, especially amongst professional musicians. He created a unique, mediated and distinctly Lebanese bossa nova style, which has been highly popular and influential: many Lebanese artists including Tania Saleh, Salma Mousfi and even Julia Boutros have recorded Arabic-language bossa nova that appears to be indebted to his idiosyncratic style. He has also played an important role in supporting Brazilian artists, and regularly features in his live shows musicians and dancers working in the Brazilian cultural sphere.

Tania Saleh—"Shwaiyet Souwar” live at Beirut Music Hall, 2013. This video features several musicians who regularly play with Ziad Rahbani, Xangô and Bloco Rubra Rosa.

Brazilian Music in Beirut

One night in 2008, Ziad went to a now-closed venue in Beirut called Razz’zz to watch Xangô, a Beirut-based band who play Brazilian music. After watching their performance, Ziad asked several of the band members to collaborate with him, as he loved how they played Brazilian music; a partnership that continues to the present day. Guitarist and founder Adel Minkara is Lebanese, but has family in Brazil, and spent many years studying music there. Naima Yazbek, the lead singer and a professional dancer, is Brazilian, of Lebanese heritage, and moved to Lebanon from her home city of São Paulo in 2008. They are joined by a revolving collective of Lebanese jazz musicians, including drummer Fouad Afra, bass player Bashar Farran, Lebanese-Armenian jazz pianist Artur Satyan and Kevin Safadi, a Lebanese percussionist who specialises in Brazilian music. Fouad and Kevin have also performed and recorded with Ziad Rahbani, who especially chose them to collaborate with him because of their expertise in Brazilian music.

Xangô’s repertoire is solely Brazilian: they play bossa nova, MPB, choro and samba, as well as styles from the North East of Brazil including forró and samba-reggae: all cover versions, and no original compositions. Xangô are unique in Lebanon, as they are the only band with a pop or jazz instrumental line-up who play this repertoire.[11] They play at a variety of venues, mainly bars, small music venues and restaurants in Beirut and its affluent coastal suburbs; typically in venues that would usually host rock, pop or hip hop bands, although they often perform in bars and restaurants and at more corporate events that usually book jazz musicians, adapting their repertoire and line-up to suit the crowd.

Figure 3: Xangô live at Metro al Medina, Hamra

The first time I watched Xangô perform live was at Salon Beyrouth in Hamra, West Beirut. A glamorous space of marble and glass, converted from an old Lebanese house, Salon Beyrouth is a relatively upmarket whiskey bar and restaurant that regularly hosts live music events, including jazz jams and tango nights. Many bars and venues like this have opened—and closed—in recent years, in response to increasing demand for eclectic entertainment options in Beirut. In general, the patrons are middle class or affluent young Lebanese, who have grown up in an increasingly globally-connected Lebanon, and tend to have strong international links through friends and family living in the diaspora. Although Lebanon’s economy and nightlife scene was almost totally destroyed during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90), the city centre was rapidly rebuilt in the 1990s.[12] The dividends from the reconstruction boom and subsequent economic recovery benefitted the middle and upper classes, but considerably widened the wealth gap between rich and poor, which remains the case today. These factors have led to the emergence of a thriving, competitive nightlife scene, although the recent economic downturn has led to the frequent closure of venues, and a situation of precarity for musicians and venue owners.

Through interviewing the band members and watching several of their performances in very different venues and contexts, I was made aware of the issues and tensions surrounding the performance of Brazilian music in Lebanon. For example, several band members remarked pointedly on the tensions they felt between authentic performance and commercial gain. The band often had to sacrifice elements of their ‘authenticity’ as a Brazilian group in order to obtain work. This sometimes meant changing their repertoire to include non-Brazilian music, and adapting their material to suit their audiences. I frequently heard musicians and dancers complaining that Brazilian music was often subsumed under the generic rubric of ‘Latin’, and conflated with salsa, Latin pop or even tango: often, Xangô were asked to include Latin pop hits in their set, which they either did or not did comply with depending on the gig at stake. This is especially true for freelance musicians and dancers who are employed to dance at corporate events and weddings, where for the most part, performances have to fit into a very narrowly-defined conception of Brazilian culture, based on clichéd images of Rio de Janeiro-centric cultural manifestations. Musically, this tends to mean that Rio-style samba and bossa nova are privileged over styles from elsewhere in Brazil, and visually, representations of Brazil found on event posters and online promotions often contain exoticist and clichéd images of football, beaches, carnival and mixed-race women in bikinis.

Conclusion

Although most Brazilian musicians and dancers work hard to avoid imposed stereotypes, most have to auto-exoticise and adhere to a narrowly-defined conception of Brazilian culture in order to make a living. However, through the efforts of the artists mentioned above, and others including Roberta Meirelles, a dancer, choreographer, capoerista and bloco leader from Salvador, Bahia, plus the work of the staff at the Brazil-Lebanon cultural centre, broader representations of Brazilian music and culture are becoming increasingly visible, and increasingly popular.

References

Gibson, Annie McNeill. 2013. “Parading Brazil through New Orleans: Brazilian Immigrant Interaction with Casa Samba.” Latin American Music Review 34:1, 1-30.

Khatlab, Roberto. 2005. Lebanese Migrants to Brazil: an Annotated Bibliography. Zouk Mosbeh, Lebanon: Lebanese Emigration Research Center (LERC), Notre Dame University.

Lesser, Jeffrey. 2013. Immigration, Ethnicity, and National Identity in Brazil: 1808 to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pravaz, Natasha. 2011. “Performing Mulata-ness: The Politics of Cultural Authenticity and Sexuality among Carioca Samba Dancers.” Latin American Perspectives 39:2, 113-133.

Racy, Ali Jihad. 1986. “Words and Music in Beirut: A Study of Attitudes.” Ethnomusicology 30:3, 413-427.

Ragab, Tarek Saad. 2011. "The crisis of cultural identity in rehabilitating historic Beirut-downtown.” Cities: The International Journal of Urban Policy and Planning 28, 107–114.

Stone, Christopher. 2007. Popular Culture and Nationalism in Lebanon: The Fairouz and Rahbani Nation. London: Routledge.

Toynbee, Jason and Byron Dueck. 2011. Migrating Music. New York: Routledge.

Truzzi, Oswaldo. 1997. “The Right Place at the Right Time: Syrians and Lebanese in Brazil and the United States, a Comparative Approach.” Journal of American Ethnic History 16:2, 3-34.

Biography

Gabrielle Messeder is a PhD candidate in the Department of Music at City, University of London, supervised by Dr Laudan Nooshin. Her current research is concerned with Brazilian music and dance in Lebanon, and her wider areas of interest include music and postcolonialism, transnationalism and popular musics of the Middle East and South America. She also works as a music teacher and musician, and regularly performs Brazilian and West African music in London with TalkingDRUM.

Notes

[1]This figure is from the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs website: http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=7223:lebanese-republic&catid=155&lang=en&Itemid=478, last accessed 10/3/18.

[2]It is very difficult to obtain precise figures as Lebanon has not had an official census since 1932.

[3]Thiago Oliveira, head of culture and education, Embassy of Brazil in Beirut: personal communication.

[4]These villages include Kamed Il Laouz, Ghazze and Sultan Yaacoub, Bekaa Valley.

[5]Although early compositions of the Rahbani Brothers for Fairouz did not explore Brazilian music, they did occasionally reference other genres from Latin American, such as tango and cha-cha-cha. A live recording of Fairouz’s 1961 South American tour, entitled Haflat min Brazil and Argentina (Shows from Brazil and Argentina) was released in 1962.

[6]As featured on the 1963 Antônio Carlos Jobim album The Composer of Desafinado, Plays.

[7]The bossa nova influence does not run through the entire soundtrack: the three songs sung by Joseph Saker—“Isma’ ya Reda,” “Ayesh Wahda Balak” and “Oghneyat al Bostah”—draw primarily from Lebanese urban music, rhythmically, melodically, and instrumentally.

[8]Bonfã’s “Manhã de Carnaval” was originally recorded for the soundtrack to the 1959 Marcel Camus film Orfeu Negro, or Black Orpheus.

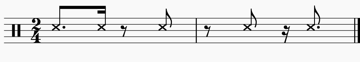

[9]The ‘bossa clave’ is a two-bar rhythmic cell used as a tool for temporal organisation in bossa nova music. The drum patterns in Ziad’s “Shu Bkhaf” feature only the first bar of the clave, not the second:

[10]See for example the Egyptian singer Noha Fekry’s version of “Shu Bkhaf” with pianist Rami Atallah.

[11]By ‘pop or jazz line-up’ I’m referring to a rhythm section (bass and drums plus piano/keyboards and/or percussion) plus guitar and vocals.

[12]For example, see Tarek Saad Ragab (2011).