PRAFODIVI: The Final Writings of PHASE 2

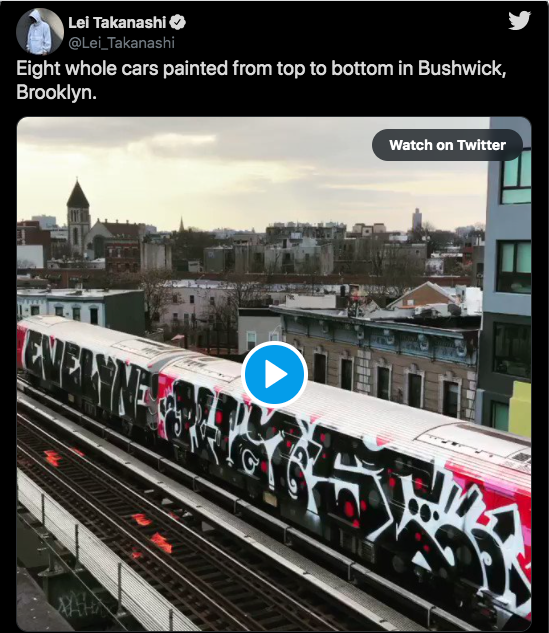

On December 12, 2019, the world mourned the loss of PHASE 2, a venerable pioneer of aerosol art and an unsung cultural figure of the modern era. The New York Times eulogized PHASE as an “intuitive, disruptive talent” who “was one of the most prolific, inventive and emulated” subway artists of all time, while musicians such as Chuck D of Public Enemy, El-P of Run the Jewels, DJ Premier of Gang Starr, and brands such as Supreme posted tributes to his pioneering legacy on social media. For the first time in decades, a line of train cars, with the mural “PHASE” painted on two of them, also suddenly appeared on the New York City subway system, demonstrating the extent of his profound influence.

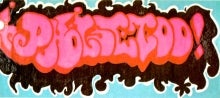

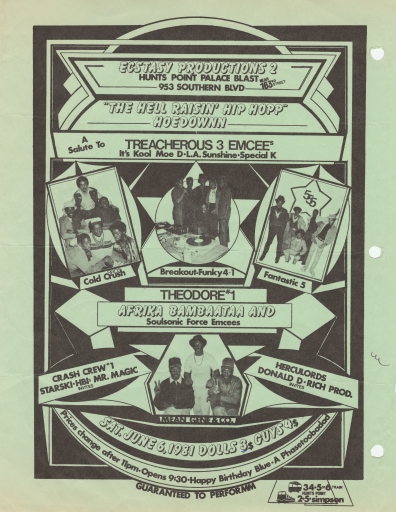

Although best known for his formative contributions to aerosol art in the 1970s—through his softie “bubble” letters, decorative drips, intricate loops, heart and arrow extensions, cloud backgrounds, and countless other aesthetic innovations—PHASE 2 also established the blueprint for early hip hop flyers, with his “funky-nous deco” designs. Subsequent flyer makers such as Buddy Esquire picked up on his style and expanded it, helping solidify the iconography hip hop was originally known for—and which continues to be used in branding and ad campaigns. It was also flyer makers such as PHASE and Esquire who first printed the term “hip hop” on handbills, denoting this new cultural movement long before any outside observers or journalists began labeling it.

On the musical side, PHASE 2 popularized several early breakbeats, including “Pussyfooter” (1976) by Jackie Robinson and “Keep On Dancing” (1968) by Alvin Cash, introducing them to prominent DJs he was affiliated with. He also formed a respected DJ crew of his own, known as the Wicked Wizards, alongside early Latino practitioners such as Raymond R and Fly T. By the time the media caught wind of hip hop in the early 1980s, PHASE 2 had become a central figure in the culture's expansion, designing the poster for and performing in the seminal “New York City Rap Tour," which was the first time hip hop practices were performed abroad. In this same year, PHASE recorded tracks such as “Beach Boy” (1982) on Tuff City Records and “The Roxy” (1982) on Celluloid Records, displaying his unique “crooning” style of MCing that combined singing with rhyming. He developed this style further into the 1990s, performing under various pseudonyms for independent labels based out of Europe. In many ways, this harmonizing style of MCing foreshadowed the approach so common in rap today—minus the autotune, out of sync vocals, and criminalized subject matter.

Never straying far from his b-boy roots, PHASE 2 also helped assemble the legendary New York City Breakers in 1983 and continued touring around the world, inspiring thousands of hip hop adherents through his art, insight, and expression. Two decades later, he was seen in the documentary The Freshest Kids (2002) sitting next to Crazy Legs of the Rock Steady Crew, explaining to him how breaking first emerged. Indeed, even prior to Kool Herc’s events in the early- to mid-1970s, PHASE was at the forefront of the dance, “turning out” parties in The Bronx through an array of unique styles he would perform with his friends. “Yo what they call up rockin’, we were battlin’ in that fashion way before anyone,” he wrote in a 1995 article for Represent, a European hip hop zine. “We had this move where we would take swipes at each other in opposite directions, kick out, drop to the floor, pop up in an abrupt and erratic movement while motioning our bodies toward one another.” These dance moves continue to be performed by an estimated one million b-boys and b-girls around the world, demonstrating how his influence has reverberated in nearly every facet of modern culture.

Just as important as his artistic innovations, however, were his intellectual interventions. In the mid-1980s, PHASE served as the creative director and co-editor of the influential street art publication IGTimes, becoming the foremost voice for artistic integrity and historical truth within the writing and hip hop movements. His essays and interviews offered lucid accounts of how both movements developed, as did his important book Style: Writing from the Underground (1998). A recurrent theme in his writings was the misrepresentation of hip hop history in the media and academia. “[T]oo much of what’s been presented, written, and supposedly documented as our origins from aerosol to hip hop is far from our reality,” he warned in one of his last interviews. “It’s a mish-mosh of sorts. And it’s not that difficult to see if you look further.” His refusal to compromise the integrity of the culture he helped spawn often made him persona non grata among so-called “experts” who perpetuated the very myths he debunked.

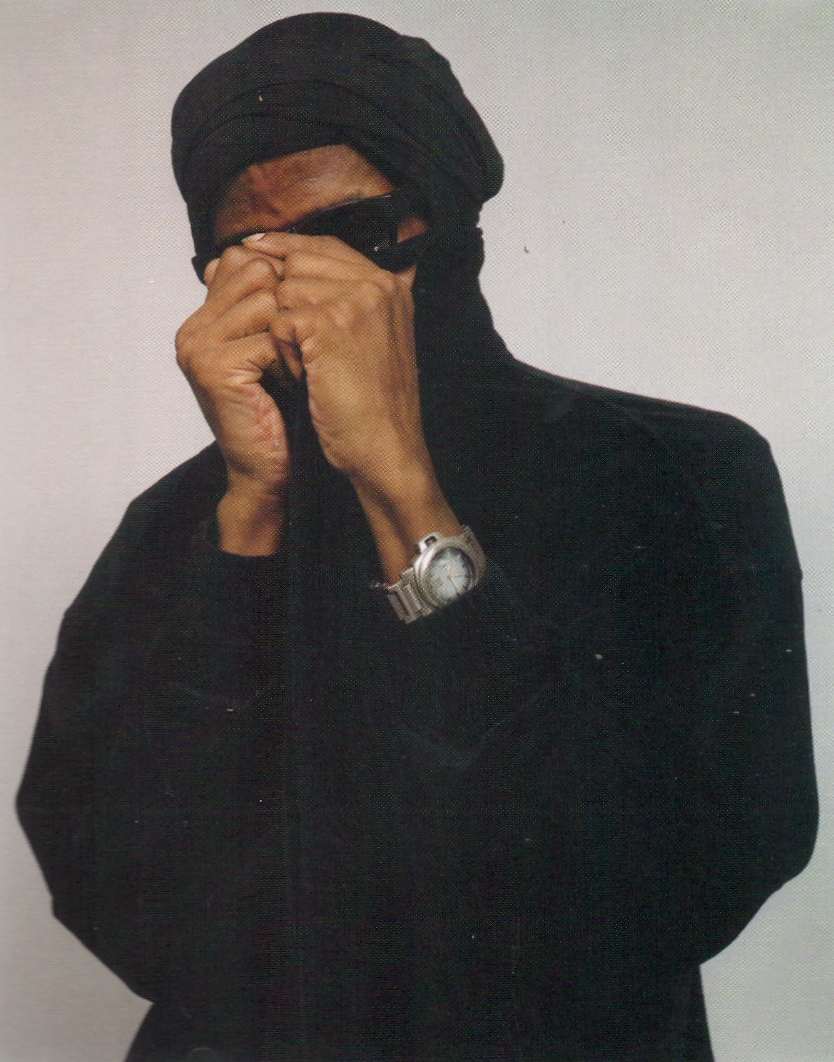

In the context of such distortion and exploitation, PHASE also maintained a relatively low profile. Many described him as being on “on the incognito tip” and living “an existence of quiet anonymity, despite his legendary status within the subculture.” The following recollection from MC and producer Lord Finesse is indicative of the inconspicuous and humble character PHASE is remembered for having. “Unknown to most we grew up together in Forest Projects in the Bronx ‘same building.. same floor,’” Finesse revealed in his tribute to the pioneer. “I never knew he was a writer until I became an artist and was running into him in different parts of the world . . . I just knew him as my next door neighbor before that.”

When it eventually became public that PHASE 2 had passed away from amyotrophic lateral sclerosi (“Lou Gehrig’s Disease”), many were saddened by his loss and the unexpected nature of the news. "Though PHASE was as private about his illness as he was about his personal life,” explained his longtime friend and IGTimes collaborator Dave Schmidlapp, “his demise came kinda sudden the last few months.” Schmidlapp added that only a few close to him were aware of his condition and at his side in his final months.

Yet, even while battling this deadly disease, PHASE continued to share inspiration with the world, producing several hundred new writings and sketches for publication from his hospital bed. This hybrid collection of literature and art, which is currently being considered for distribution, encapsulated his vast creativity and knowledge of numerous topics: art, music, movies, history, sports, humor, dance, health, politics, and society. Once again, championing historical truth figured prominently in these writings, as did his reflections on the beginnings of hip hop and his personal artistic career. Most of these passages were also written as rhymes—which PHASE referred to as “flowetics”—leaving one marveling at how he was able to articulate so many thoughts through such complex lyrics. There are also various song and movie listings, words of wisdom, and special dedications interspersed throughout the project.

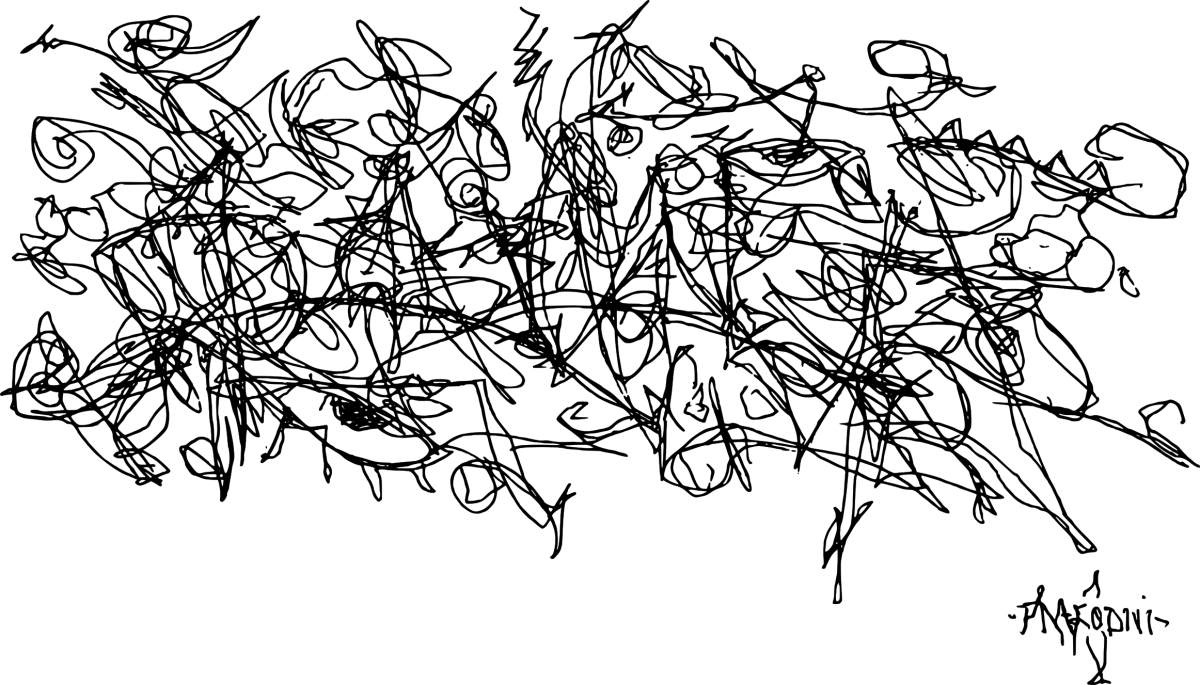

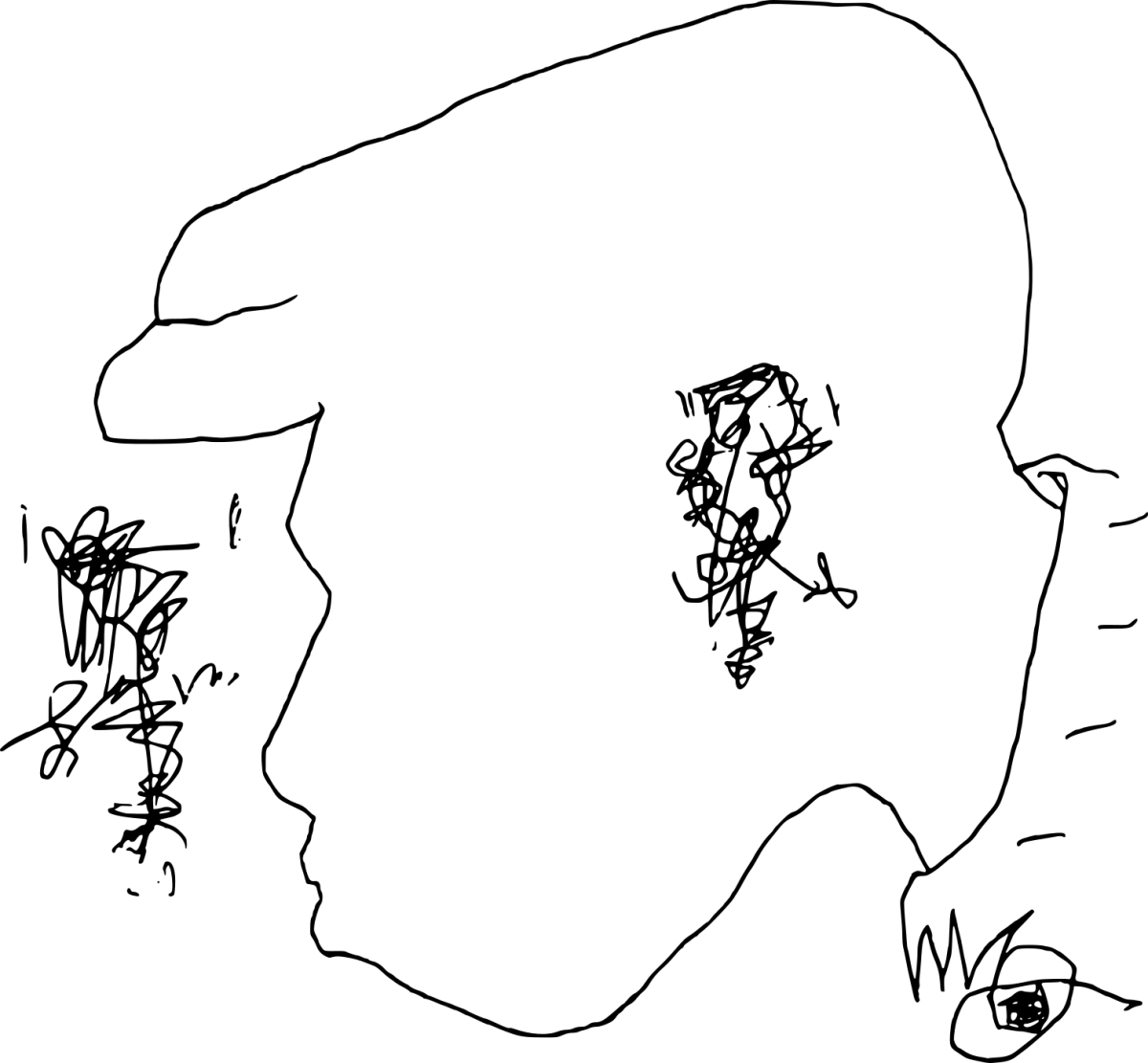

Accompanying these writings were calligraphic symbols PHASE referred to interchangeably as “spiraglyphs,” “zymbols,” and “phaseoterics”: unique designs, reminiscent of logographic script, which he aligned vertically alongside his poems. As with his texts, these drawings were all done in black ink on white paper, usually in one sitting. There are also various sketches of silhouettes, logos, aquatic creatures, piercing eyes, and alienesque beings, some of which are grounded in his previous work, but also others that explore wholly new artistic terrain. For instance, there are several renderings of fish and crustaceans that seem to refer to ancient religious symbolism, and which morph into facial outlines, reconstructed letters, and collages of symbols with abstract imagery. There are also drawings that coincide with the stories in his passages, reaffirming the interconnected, yet uncontained, character of this final project. Both the images and texts are also repeatedly signed under the pseudonym PRAFODIVI, whose meaning remains largely unexplained.

Perhaps the most powerful aspect of this work, however, is the context in which it was all produced. “When he lost movement in his right hand,” Schmidlapp was quoted as saying, “he continued with his left until he couldn’t draw or write anymore." Whereas most people would resign in the face of such debilitation, PHASE continued to create new styles and innovate old ones, refusing to bend to his circumstances. Indeed, he seemed to be willing his way through his condition with whatever means were at his disposal: basic pen and paper, the energy remaining in his less dominant hand, and his seemingly endless imagination. One of the many words of wisdom featured in the text reads, “WHERE THERE IS NOTHING, CREATE SOMETHING,” a prominent motto he lived by to the very end. Cut off from the world and confined to a hospital bed, he channeled this motto into a culminating endeavor full of deep reflection, which offered insight into both who he was and what he stood for. In this way, he left behind more than a final account of his thoughts and life. He left behind a testament to his undying spirit of resilience.

Serouj 'Midus' Aprahamian is a longtime practitioner of breaking, popping and underground hip hop dance styles. He also complete his PhD in Dance Studies from York University, with a focus on breaking and hip hop history. His scholarly writings have appeared in the Journal of Black Studies, Dance Research Journal, Oxford African American Studies Center, and the forthcoming Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Dance Studies. He can be reached at serouja@yorku.ca