Reading Opera Through the Visual Arts

Each month, Ethnomusicology Review partners with our friends at Echo: A Music-Centered Journal to bring you Crossing Borders, a series dedicated to featuring trans-disciplinary work involving music. ER Associate Editor Leen Rhee welcomes submissions from scholars working on music from all disciplines!

This month's author is Devin Beecher. Devin is a PhD student in Comparative Literature at UCLA. He is interested in the intersections between literature, music and medicine. In his latest research he studies the standardization and rhetoric of personal illness narratives.

* * *

Béla Bartók’s opera Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, first performed in 1911, has an abstract story and enigmatic score which make a metaphorical interpretation unavoidable. Here, Duke Bluebeard becomes the “Everyman,” and Judit the “Everywoman,” or sometimes even the “Eternal Eve.” The two attempt to enter into a relationship, which apparently takes place entirely within the psyche of the Everyman. This is a gloomy place, whose darkness primarily conceals certain memories that the Everyman must not reveal to his Everywoman. She, however, wants this knowledge—perhaps because she thinks it would be healthy for the man to divulge it, or because her conception of a relationship involves mutual understanding, or because she is just too damn curious, as many interpreters seem to think. Eternal Eve deviously convinces Everyman to reveal his memories to her, but in doing so she has doomed their relationship, or, more specifically, herself. She disappears behind a door of the castle of his memories. One writer who generally supports this interpretation claims that its misogynistic aspects can be moderated by recognizing that the situation is entirely reversible—women too have their impenetrable secrets.[1] These, however, are not suggested in the opera itself. Rather, Judit is transformed from an initially free human subject into a prisoner and finally into a metaphor, both in Duke Bluebeard’s Castle and also in this interpretation.

Analysis of the music is often metaphorical as well. This centers around interpreting the two primary keys of the opera, F sharp and C, as symbolizing, respectively, darkness and light. In its staging, the opera begins in darkness and ends in darkness, with the lightest part being in the middle, at the opening of the fifth door; the two keys follow this progression as well. That they are a tritone apart furthers symbolizes this light/dark opposition, since this is, in traditional harmonics, the most distant two keys can be. This all can be taken metaphorically to represent the relationship of Bluebeard and Judit, who begin and end the opera in isolation from each other.[2] Another favorite locus of interpretation is the function of minor seconds and major sevenths in the work. These two intervals are inversions of each other; Bartók explicitly recognized this in Number 144 of Mikrokosmos, entitled “Minor Seconds, Major Sevenths.” The minor second appears in the opera whenever Judit encounters blood on the walls or behind the doors; this has led scholars to refer to it as the “Blood Motif.” Major sevenths, founded on either major or minor triads, have been linked in Bartók’s works to the concept of love, as he once referred to the chord as the “leitmotif” of a woman he loved at the time. The chord is featured prominently in the opera, at certain points which make the symbolic connection with love very natural. The fact that these intervals are inversely associated suggests by metaphor that the same is true of the themes of blood (and death and suffering and darkness) and love (and life and joy and light).[3]

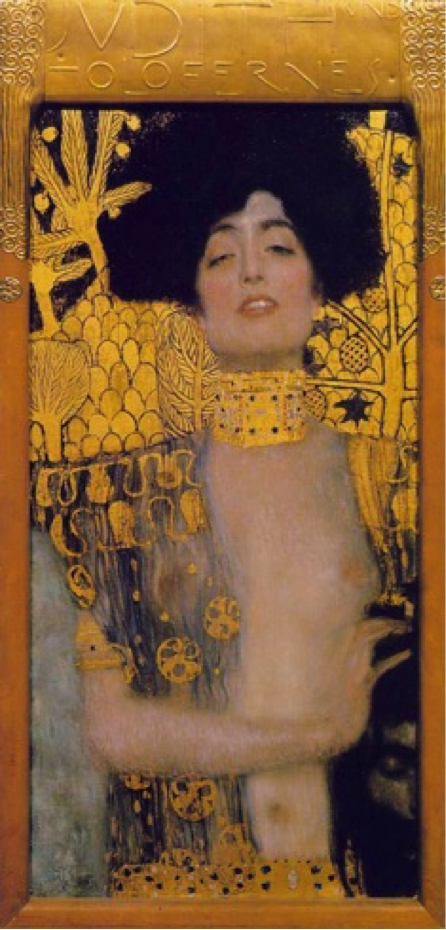

Gustav Klimt, Judith (1901)

In the 1901 Judith, manfulness can be physiognomically read from her strong chin and arm, animosity and superiority from her up-tilted head, sexual delight from her orgasmically half-closed eyes. Her teeth glint appealingly and her nakedness is so luminescent that the fabric she wears cannot conceal it, yet the viewer is both warned off and oddly drawn in by the repelling sight of Holofernes’ head.

Gustav Klimt, Judith (1909)

In the 1909 Judith, the deadliness of Judith is symbolized by her serpentine pose, mirrored and emphasized by curves of the fabric hanging from her body. The appealing color of the 1901 Judith’s skin is transformed in the 1909 version into a livid and frightening pallor, and her strong hands have become vulturous claws. Read together in this way, the two paintings suggest that the viewer ought to beware of this Judith, for she will cut off your head and turn ugly besides. Judith, herself, is reduced to standing metaphorically for the many things of which her male spectators are terrified.

However, by focusing on the locus of action in the Judiths, one can see an alternate story, primarily told through metonymy and synecdoche, which reinstates the subjectivity of Judith as manifested through her act. The action of the story is, obviously, Judith’s decapitation of Holofernes, though at first glance neither painting directly depicts this; rather, they seem to be static and symbolic representations of Judith, shown as posing rather than as acting. However, if we analyze the specific point of contact between Judith’s hand and Holofernes’ head—precisely where the action takes place—it becomes apparent that it displays a kinetic tension which disrupts the static iconicity of the paintings.

In the 1901 Judith, her right hand is bent backwards at an unnaturally acute angle, farther than a hand could typically bend without some sort of opposing force acting on it. This force must come from the head, since that is what the hand touches, and particularly from the part of the head not represented within the painting. What about it presents resistance, one must ask: perhaps Judith is pressing it from the other side with her other hand, or perhaps the head is still partially attached to the body and she is forcefully trying to dislodge it. Either way, read like this, the painting becomes representative primarily of the act—the beheading of Holofernes—a metonymical function centered around the contiguous and causal relationship of hand and head. Focusing on the act as act, rather than as metaphor for manfulness, chastity, or castration, lets us reappropriate it rhetorically as a synecdochical representation of Judith’s subjectivity (given the assumption that a subject’s compounded actions constitute the subject itself).

The 1909 Judith can be read similarly. The detail is again the hand and the head, and the exceptional element is that Judith is not really grasping it at all. Her hand is clawing at, rather than clutching, Holofernes’ hair. Judith is apparently not actually holding the head in this painting, but rather is in the process of dropping it. We then realize that the ambiguous fabric covering the head’s lower half is actually Judith’s bag, and the painting as a whole represents Judith’s next significant act: hiding the severed head in her bag so as to transport it back to Bethulia. The serpentine curve of Judith’s body and of her clothes can now be seen as effects of her turning to exit Holofernes’ camp, rather than as symbolic evidence of the dangerous essence of her character. In this painting, as in the 1901 version, finding the point of action serves to disturb the dominant metaphorical interpretation of Judith. That this specific point is minimized and placed in the far corner of both paintings indicates the tendency of viewers and interpreters to strongly favor the other reading, symbolized and supported by Judith’s metaphorically fertile and centrally depicted body. In both paintings this element enables a reading based on the metonymical relationship of hand to head which emphasizes the act as a synecdochical representation of Judith’s subjectivity.

In Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, the blood motif can be read not only as a metaphor for death, but also as evidence of the work’s displacement of its disguised violence. The clue for this reading is the odd discrepancy between the extreme bloodiness of the two traditional stories that the characters’ names evoke, and the lack of explicit violence in the plot of Bartók’s opera. The story of Judith and Holofernes centers around a necessarily brutal beheading, which I discussed earlier. The second story is no less grim: it is that of Bluebeard, a character based upon a 15th-century serial killer who first appeared in a fairy tale written by Charles Perrault in 1697. There have been many retellings of this story, all of them far bloodier than Bartók’s version: in some, the previous wives are slaughtered; in others, Bluebeard’s wife also is killed; in others it is Bluebeard himself who is killed by the wife’s brothers. Nobody is literally killed in Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, and in this way it is a very bloodless retelling of the story. There is, however, the blood that Judit finds everywhere: on the castle walls, and in the torture chamber, armory, treasury, garden and surrounding estate. This suggests that it is ultimately reductive to read the blood and the blood motif merely as metaphors in the light/dark and life/death binaries which support the allegorical model of the opera that I outlined earlier, especially as this model depicts Judit as responsible for the turn toward darkness. Rather, we should pursue an interpretation in which these elements function as displacements of the blood found in the original tales of Judith and Bluebeard.

Though it is not recognized as this at the time, the first appearance of blood (and the blood motif) comes when Judit, feeling her way forward in the darkness, touches the wall and finds that it is “sweating.” Again, the contiguity and causality involved in the gesture of touching allow us to pursue a metonymical reading of the blood, suggesting that it has an existential relationship with someone in the opera. If we accept the castle as a metaphor for Bluebeard’s soul, then it is logically his blood found throughout. (This is precisely the opinion of conductor István Kertész. He says, of Bluebeard, that “the blood Judith keeps finding everywhere is his blood, his suffering. The tears of the sixth door are his tears.”[5]) However, if we reverse our notions of literal and figural, the castle becomes very obviously a literal prison for Judit and the three wives before her. The blood is thus theirs, not Bluebeard’s. The libretto even provides evidence for this: when the three imprisoned women are revealed, Bluebeard says that “they have bled to feed my flowers.” By reading elements of Duke Bluebeard’s Castle and Klimt’s two paintings of Judith as non-metaphorical rhetorical devices, I hope to have revealed the absurdity of an interpretation that portrays Judit as the antagonist and Bluebeard as the victim of the opera. I hope also to have countered the excessive allegorizing of these stories found in other interpretations, exposing instead the literal violence not quite shown in the actions of Judit and Judith.

[1] David Johnson. Liner Notes. Bluebeard’s Castle. CD. (CBS Masterworks/Hungarian Record Company, 1988), 11.

[2] Carl Stuart Leafstedt, Inside Bluebeard’s Castle: Music and Drama in Bartók’s Opera, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 55-61.

[3] Leafstedt, Inside Bluebeard’s Castle, 69-84.