Research as Sites of Memory: Musings on N.E.R.D. and Tyler, the Creator

What is a false memory? A sonic one at that? Is it when a person remembers things, events, places, feelings, thoughts and spaces that were untrue? I remember events that I never experienced before. Toni Morrison did too, and look at the worlds she invited her readers into. She explains her writing process stating, “My route is the reverse: the image comes first and tells me what the ‘memory’ is about” (114).

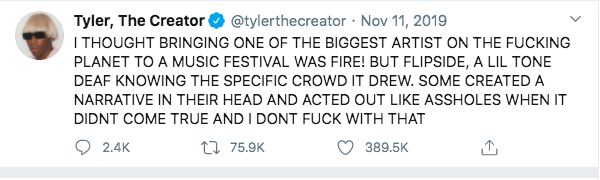

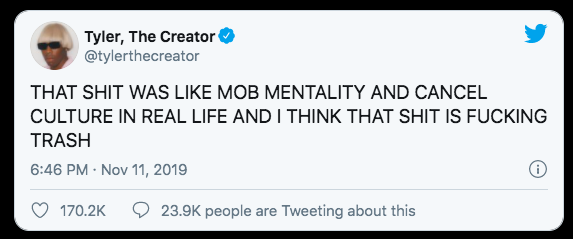

My route, like Toni Morrison’s, derives from the image first, or rather the films and sounds that accompany it. I watch it over and over, reliving a moment whether it belongs to me or not. I imagine the contexts in which the polyphonic sounds and sights are meshed together, peeling back layers of dissonance and calamity that reveal themselves to the senses. The too timely, rhythmic chant —Aye! Aye! Aye!—against the lyrics of a rap song by a mostly white audience and the pockets of black kids swaying to Drake underneath the boos of of entitled fans at Camp Flog Gnaw festival.

Drake's Closing Performance at Camp Flog Gnaw festival 2019

So recollection, for me, requires an inventive imagination, it harnesses a truth that exists in the cosmic realms of concert performances where sweat, screams, singing, and swearing collide into bodily perception. And though I wasn’t there – I was too poor to be there, to snag a 3 Day Pass or one day ticket in time before they sold out after being online five minutes–I could be like Toni, “I could try to reconstruct the world” they experienced just for those few minutes before festival fatigue and rage hits. I imagine many experiences. And I’d want to take it all in, like feeling of the rush of a cool November wind spitting in my face while on the carnival rides, or dashing from stage to stage to get a glimpse of my favorite artists in between rapid bites of the overpriced snacks loaded with sugar and cholesterol. I want to feel all of it, my little body getting knocked around in mosh pits, the pulsing vibrations from speakers I feel in my toes and teeth, the brief pauses between sets as my turtle peeks while in long lines for portable toilets.

Yes, the act of imagination is bound up with memory. It is subjective like all knowledge is, and perhaps elusive from fact. I wonder what it might mean to understand that facts engender sonic imaginations, the fact of a moody falsetto, or the whistling of a descant, or a bellowing howl. In fact, I often imagine what it would be like to interview subjects of my research, Pharrell Williams, and Tyler, the Creator.

Here again Morrison does the work for me. Describing the dynamics of interviewing her mother about what her interior life was like, she says, “She [Morrison’s mother] will give you the most pedestrian information you ever heard, and I would like to keep all of my remains and my images intact in their mystery when I begin. Later I will get to the facts. That way I can explore two worlds–the actual and the possible” (117). It’s so easy for me to explore two worlds, I thought with social media at my finger tips, the tweets, gifs, and festival vlogs.

Which begets the curious question of how to explore the actual with the possible when interrogating the interior lives of uber celebrity musicians? In a field that prides itself in uncovering the science of the musical facts, the figures, the notations, and the images of Othered sonic cultures, all measured, logical, and methodical. It is intimidating to think of where I might position my scholarship of Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo as sonic imagineers and architects of cosmic sensations. And I've read that book Paul Lester wrote, In Search of Pharrell Williams. It left me wanting, in search of something different than the same old accounts of studio sessions and scandalous celebrity culture music journalists pillage through. Surely, a musical account would bypass the usually chart statistics with their empty qualitative positionality. What does it mean for a Black woman musicologist to write the sonic histories of men, Black men, Asian, Nerdy men, very rich men, like that of Pharrell Williams, Chad Hugo, Shay Haley and Tyler Okonma? Those musicians who ooze masculine energy and play along an imaginative spectrum of gender, and sexuality. Those Neptunes men-N.E.R.D.(y) men, who shaped a generation of Black and Asian musicians in the 1990s and 2000s before they could really grasp what their legacies could be. How easy was it for them to imagine the future, caught in between racing Lamborghinis and half pipes, revived arcade games from their youth, and generously hot-headed egos? Maybe my role is to question, what was it really all about?

N.E.R.D. - Life as a Fish

Morrison explains writers are bound to special kinds of imagination, “It is emotional memory–what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our “flooding”(119). I like to think in using the word “writer,” that she includes song writers too. Because the ties to water in the Neptune’s production and N.E.R.D.’s music are not lost on me. Sometimes I like to daydream while listening to “Life As A Fish,” where I hear the lyrics as a first hand account of one fish wading through their fellow underwater creatures’ historical memories of an initial human contact. This is the freedom a Morrison-minded imagination, or an Afrofuturistic memory, can bring to historical conversations.

Afrofuturism is a recollection of memories that Black people have of our past, present, and future selves. When applied to music and cultural production, Afrofuturism opens listeners to worlds of remembering through oral and aural and visceral knowing. Acoustemologically aligned, our feelings and perceptions of timbres—those recorded and plugged in are intentionally situated through time— thus, uncovering our most powerful instances of identity. If we let them. Should we let them, I’d hope for the courage to flesh out our worldview(s) beyond their limitations, calling into question the socialization of sound. So seeing sounds, bathing in them feeling those grindingly good vibrations through our legs and our chest are faithful reminders of all the beauty we have chosen to be.

References

Lester, Paul. 2015. In search of Pharrell Williams. London: Omnibus Press.

Morrison, Toni. 1995. “The Site of Memory.” In Inventing the Truth, edited by William Zinsser, 83–102. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

This text is a revised version of "Imagining a Musicological Truth: On Toni Morisson's The Site of Memory," originally published on the author's blog "Danie Does Musicology".