Review | "Get On Up," directed by Tate Taylor

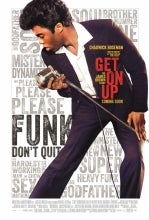

Get On Up. Directed by Tate Taylor. 139 minutes. Imagine Entertainment, 2014.

Reviewed by Ben Doleac

In the opening shot of Tate Taylor’s Get On Up, the long-overdue James Brown biopic that opened nationwide three weeks ago, the aged Brown makes a deliberate stride down a hallway as voices from his past echo around him on the soundtrack. The scene is dismayingly reminiscent of the satirical 2007 film Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, in which Tim Meadows explains the elderly rocker’s preshow brooding by solemnly noting, “Dewey Cox needs to think about his entire life before he plays.” After such a beginning I feared the worst, but while Get On Up hits many of the requisite clichés of the rock-biopic, its shortfalls and lapses into sentimentality are expertly camouflaged by an ingenious structure that leaps between periods of his life almost seamlessly. Critics like the AV Club’s Ignatiy Vishnevetsky and Kenneth Turan at the Los Angeles Times have criticized the film’s freewheeling, episodic framework as incoherent, but it serves Taylor’s thematic focus on family and the individual psyche while at the same time undercutting some of the melodramatic excess. The gaps it leaves in Brown’s story and its wider significance are problematic in a number of ways, but more on that later.

From a 1988 incident where Brown, brandishing a firearm, disrupts a meeting at one of his businesses – a confrontation that would ultimately land him three years in prison – the film ricochets to scenes of his traumatic childhood in South Carolina. Literally raised in a windowless shack in the woods, the young Brown witnesses the departure of his mother after one too many beatings at the hands of his father Joe. Shortly thereafter, Joe leaves with his son for Augusta, Georgia, scratching out an existence as a gambler and petty thief and handing James off to his aunt, the madam at a local brothel. As the film suggests and R.J. Smith’s excellent biography The One makes explicit, Brown’s formative experiences of profound deprivation and abandonment may have set the stage not only for his ruthless ambition but for the megalomania, anger, and insatiable thirst for control that would prove personally and financially calamitous in the final decades of his life.

Eerily, almost unfathomably, Chadwick Boseman embodies Brown – his electric stage persona, his incisive musical brilliance, his narcissism and the sense of abandonment that undergirds it, and most of all his singular intensity. All are on glorious display in the film’s several concert scenes. Boseman’s remarkable approximation of Brown’s reedy Georgialina drawl and quicksilver dance moves have attracted widespread acclaim, but it is his grasp of the singer’s penetrating gaze that elevates several scenes beyond boilerplate drama. Without such a capable actor, Brown’s tense reunion with his mother and a late-life a capella rendition of the ballad “Try Me,” dedicated to his estranged bandmates Bobby Byrd and Vicki Anderson, would come off corny or worse; instead, they’re transcendent.

While some have crowed about the remixing and tidying of the original Brown recordings that provide the soundtrack for the live sequences, in fact their renewed clarity lends further immediacy to what are already the most vital moments of the film. Glimpses of Brown stealing the show from Little Richard at a bar in Georgia and commanding an ensemble of 20 musicians and dancers with every step of his skittering feet in Paris offer an explication of his magnetism and his genius that the patchwork narrative lacks. In the film and in the many concert clips that are available on YouTube, Brown pleads, screams, shimmies, camel walks, drops to his knees and raises himself up, over and over again. Most of all, he sweats. Not for nothing did he dub himself “The Hardest-Working Man In Show Business”; for Brown, funk meant hard work, and with hard work came both existential release and financial reward. Cutting between Brown’s fast feet, his damp brow and the expertly coordinated movements of the ensemble, director Tate Taylor conveys the transformative power and churchlike pathos of his performances. The tremendous effort that went into staging the James Brown Show almost 300 nights a year, and its impact on the young blacks who turned Brown’s funk into a musical and cultural revolution, are unfortunately left mostly unexplored.

The white, Mississippi-born Taylor is most famous for his direction of the 2011 film The Help, an Oscar-winning narrative of black female servants struggling against societal oppression and subordinate treatment at the hands of their white employers in the early 1960s South. That film generated no small controversy for its sanitized depictions of race relations and its sentimental invocation of the “mammy” archetype. Unlike the maids in The Help, however, Brown was a real-life icon, perhaps the foremost celebrity exemplar of black pride and achievement after Muhammad Ali. It’s curious, then, that the uproar over Taylor’s helming of the Brown biopic has been relatively muted. The most incisive criticisms I’ve read come from historian Rickey Vincent, who points out a series of critical omissions in the film in a recent article on the website Hip Hop and Politics. In his focus on familial pathos and psychodrama, Taylor ignores the sociopolitical context of Brown’s rise to stardom almost completely. Regardless of his egotism or his sometimes self-contradictory political opinions, Brown was a black hero because he had forged a sound and built a business empire on his own terms, not those of a racist pop marketplace. Although Taylor hints at how Brown subverted the racial pecking order of the music business in an exchange where Brown schools his white manager, Ben Bart, on the economics of touring (“If I’m spending my money on own money on the show, I’m gonna be the business, too,” Brown avers), he can’t resist making Bart into something of a benevolent father figure – a man whose wisdom and guidance makes up for the sins of Brown’s absent father, Joe. In fact, in his autobiography Brown credits his father with instilling in him the value of hard work: “He was never without a job for more than five days in his life,” Brown reflects.

What Brown did not accept was his otherwise assertive father’s deferential attitude towards whites. In tandem with his almost superhuman work ethic, Brown’s refusal to compromise or accept the limits set for him by a racist white power structure turned him from a mere star into a cultural icon as the compromises of the Civil Rights era gave way to Black Power’s insistence on race pride and self-determination in the mid-1960s. Yet just as it only hints at the institutional bigotry that immiserated the young Brown and his family in 1940s Augusta, Get On Up offers little indication of Brown’s relationship with his black audience or with the cultural politics of the era.

It’s no coincidence that as Brown took greater charge of his business affairs and his increasingly militant public image, his music also became more radical. Beginning with the 1965 single “Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag” and continuing with “Cold Sweat” (1967), and “Mother Popcorn” (1969), Brown pared down the chord changes and discrete sections of traditional pop song form, foregrounding the rhythm section and focusing almost exclusively on rhythmic rather than melodic development. The resulting musical style was eventually dubbed “funk.” Built on repeating, interlocking and heavily syncopated lattices of guitar, bass, drums, and horns, it sounded like nothing else on the radio. As Robert Palmer writes in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll, Brown’s critical innovation was “to treat every instrument and voice in the group as if each were a drum.” In a likely fictionalized but nonetheless wonderful scene, Get On Up illustrates Brown’s breakthrough as occurring during the first rehearsals of “Cold Sweat,” where a frustrated Brown asks each of the band members to tell him what instrument they are playing. “A horn?” responds saxophonist Maceo Parker. “No, drums,” Brown replies. To guitarist Jimmy Nolen, he states, “The guitar? No, you’re playing the drums.” The band soon gets the picture, and the funk bursts forth in full flower.

It’s foolish to expect any but the most cursory musicological insights in a mainstream feature film, but even a glimpse of Brown’s visionary bandleading is more than most music biopics offer on the creative process. The film only hints at Brown’s epochal impact on popular music around the world; already a soul music pioneer when he developed funk, his formal innovations ultimately laid the groundwork for disco, hip-hop and the Nigerian popular style known as Afrobeat. Rickey Vincent’s 1996 book Funk explores not just the stylistic roots but also the spiritual and political dimensions of the musical revolution Brown wrought, devoting extended attention to the work of Brown’s disciples in Sly and the Family Stone and, especially, George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic collective. Vincent’s recent Party Music (2013) is even better. Though nominally a history of the Black Panther Party’s little-known funk band, the Lumpen, the book functions more broadly as a study of the intersection between black radical politics and popular culture in the late 1960s, brilliantly synthesizing histories of the broader black nationalist movement in America, the youth counterculture, and black popular music. An especially insightful chapter considers Brown’s influence on transnational black music and black power politics, at the same time touching on the stories of third-world black musical icons Bob Marley and Fela Kuti. More explicitly musicological explorations of Brown’s work include Anne Danielsen’s Presence and Pleasure (. Though the Norwegian Danielsen’s prose is stilted and sometimes clumsy, her book stands as the only in-depth examination of just what it is that makes funk music move and groove. Alexander Stewart’s illuminating article “Funky Drummer” (2000) traces the roots of Brown’s eccentric rhythms to New Orleans musicians such as Professor Longhair and Earl Palmer. Finally, Jim Payne’s 1996 book Give the Drummers Some profiles several of the drummers who passed through Brown’s band, including the unheralded but crucial Charles Connor and Clayton Fillyau.

Along with the above works, The James Brown Reader, which collects writings on the singer in the popular press that span more than 50 years, goes some way towards establishing a cultural context for Brown’s work and illustrates how that context shifted over the course of his long career. Capturing Brown’s outsize aura and unremitting intensity on the page is like trying to bottle lightning, but Doon Arbus’s remarkable 1966 profile “James Brown is Out of Sight” succeeds as well as Jonathan Lethem’s 2006 Rolling Stone feature “Being James Brown.” But the best starting places for those looking for greater insight into Brown’s life and work are his own 1986 autobiography, The Godfather of Soul, and R.J. Smith’s recent biography, The One (2011). The autobiography offers ample illustration of his self-reliance and bootstrap philosophy of racial uplift, tying his grueling efforts to transcend race and class barriers to the larger African-American struggle for survival in a hostile society. Fascinatingly, it also breaks down the inspirations for his stage show in the flamboyant sermons of the evangelist preacher Charles Manuel “Daddy” Grace and the ringside exploits of the caped wrestler Gorgeous George. Unsurprisingly, Smith’s posthumous Brown biography demystifies Brown’s legend somewhat, detailing the opportunism behind his political entanglements in the late 1960s and revealing how abominably he treated both his bandmates and lovers for decades. But it also underlines the enormity of Brown’s achievement by establishing that the childhood existence he transcended was far bleaker than he ever let on, and by exploring how he forged the disparate talents of his many musicians into an unprecedented, fiercely idiosyncratic sound that was ultimately his alone. Both books are full of far more striking and complex insights than Get On Up can hope to provide.

Like every biopic, Get On Up is a selective history by necessity. Its unfortunate elision of social and political context reflects not so much the blinkered vision of its director and screenwriters, whose treatment of the material is generally sensitive and intelligent, but the racism and cowardice of Hollywood as a whole. Could a black filmmaker have gotten the industry’s support to tell this story? Somebody ask Spike Lee, who was originally slated to direct before the producers replaced him with Taylor. Yet it’s blessing enough that a James Brown biopic exists at all, and Get On Up is a supreme, audacious entertainment. Ray and Walk the Line, the two most successful recent rock biopics, sparked renewed interest in their subjects, and if there’s any in the world Get On Up should do the same for a man whose musical legacy looms even larger than Ray Charles or Johnny Cash. But here’s hoping as well that it prompts new fans and listeners to dig a little deeper into Brown’s history, his cultural resonance, and the utterly sui generis body of work he left behind.

References

Brown, James with Bruce Tucker. 1986. The Godfather of Soul. New York: MacMillan.

Danielsen, Anne. 2006. Presence and Pleasure: The Funk Grooves of James Brown and Parliament. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

George, Nelson and Alan Leeds, eds. 2008. The James Brown Reader. New York: Plume.

Payne, Jim. 1996. Give the Drummers Some! The Great Drummers of R&B, Funk & Soul. Katonah, NY: Face the Music Productions.

Smith, RJ. 2012. The One: The Life and Music of James Brown. New York: Gotham Books.

Stewart, Alexander. 2000. “‘Funky Drummer’: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music.” Popular Music Vol. 3, No. 19: 293-318.

Vincent, Rickey. 1996. Funk: The Music, the People, and the Rhythm of the One. New York: St. Martin's Griffin.

---. 2013. Party Music: The Inside Story of the Black Panthers' Band and How Black Power Transformed Soul Music. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books.