Review| Longing for the Past: The 78 rpm Era in Southeast Asia

Longing for the Past: The 78 rpm Era in Southeast Asia, Edited by David Murray with Essays and Annotations by Jason Gibbs, David Harnish, Terry E. Miller, David Murray, Sooi Beng Tan, and Kit Young. Atlanta: Dust-To-Digital, 2013. [272 pp. ISBN-13: 9781938922572, Hardcover: $57.50].

Reviewed by Meghan Hynson / Duquesne University

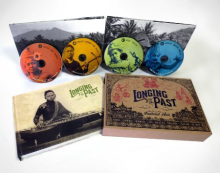

Inspired by the Vietnamese aria form vọng cổ meaning “longing for the past,” Longing for the Past: The 78 rpm Era in Southeast Asia captures a distant musical and historical era in Southeast Asia through an extensive collection of early recordings and scholarship.[1] The box set features 90 tracks of restored and re-mastered 78 rpm recordings organized onto four CDs, offering listeners a rich, yet diverse, aural tour of nearly six decades (1905-1966) of music in the region. The CDs are beautifully complemented by a 272-page hardcover book of annotations and essays by prominent ethnomusicologists, as well as vintage photographs, postcards, and record art.[2]

Collections such as this one are particularly special, because aside from bas-reliefs and ethnocentric European travelogues, early colonial recordings are some of the oldest extant sources of Southeast Asian musical history. As one of the contributing authors, David Harnish, states, “most of the recordings available in this collection are either relics of history or are antecedents of the traditions we can still hear today,” and several of the tracks are of music or musical instruments that can no longer be found in Southeast Asia (59). The specific focus on the 78 rpm genre also contributes to studies of colonization and the sound recording industry while harkening back to a time when Southeast Asian borders were in flux.[3]

The accompanying hardcover book begins with a preface and introduction, detailing why the 78 rpm format was chosen and how European colonial involvement in the region was integral in developing a recording industry in Southeast Asia. “Part I: The Record Industry in Southeast Asia” discusses the emergence of this industry in two parts. In “The First Wave,” the focus is on colonial record companies and how European and American attempts to establish themselves in the local marketplaces led these labels (Gramophone, Columbia, Victor, Pathé, Odeon, and Beka) to record almost any type of music. This resulted in the extremely large pool of 78 rpm recordings from which this set is derived. The second section, “The Rise of the Local Labels,” then examines how European record companies acted as agents and the inspiration for local Southeast Asian entrepreneurs to create their own local labels (Chap Kuching, Chap Singa, Pagoda, Toe Na Yar, Irama, and Lakotananta).

“Part II: Southeast Asia and its Music” then provides a brief musical, cultural, and historical background on each of the countries featured in this collection, preparing listeners for “Part III: The Records,” in which detailed listening notes for each of the tracks can be found. Each recording is expertly described, including background information on the genre, names and descriptions of performers and musical instruments, and details on the label that made the recording. Even so, the information seemed a little too concise at times and the organization of the tracks was questionable. For example, recordings from a few countries can be found on different discs and the editors don’t mention the reasons for such an organization. Perhaps organizing all recordings from a single country onto one disc would have made this collection more user-friendly. With this in mind, I have organized my review of each disc by country.

Disc A: Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia

Vietnam

Disc A begins this set with twenty-two tracks from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.[4] The music of Vietnam is recorded onto eleven tracks of this CD, presenting vọng cổ arias (“longing for the past”) on tracks 1, 3, and 11 and chèo cải lương, a similar type of theater that originated in 18th century northern Vietnam, on track 4.[5] The recording of the đàn bầu (one-string monochord zither) on track 8 is clear and not over electrified, capturing the complex sound of the instrument’s exclusive use of harmonics while also demonstrating classic techniques that mimic the complexity of Vietnamese tonal singing.

The lasting and profound influence that China has had on Vietnamese arts and culture can be heard on track 10 in the instrumental form of the popular cải lương theater in the hồ, or Guangdong Chinese, style and on track 12 of the Vietnamese hát bội/hát tuồng, a form of Vietnamese theater influenced by Chinese opera.[6] On track 19, Cô Năm Cần Thơ, the “nightingale of traditional music,” performs a piece in the nhạc mode, believed to be a variant of the anhemitonic pentatonic scales of Chinese music, and track 22 also features women performers through a “singing of songstresses” in an early rendition of ca trù chamber music called hát ả đào.[7] Ca huế, a similar form of female entertainment from the Cham Kingdom (7th c.-15th c.) can be heard on track 18, demonstrating South Asian musical influences on Vietnamese music, while the hát chầu văn spirit mediumship ritual found on track 15 also features a woman singer and intermediary and demonstrates elements of Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and fortune telling (104).[8]

Laos

On four of the seven tracks of music from Laos, one can hear a clear connection to Thai music, as Thailand sought to control most of Laos in the early 19th century when King Rama III invaded Laos and carried off most of the population in 1828 (101).[9] For example, tracks 16 and 17 are of Thai/Laos compositions sung to the accompaniment of the Ensemble of the Governor of Vientiane, consisting of lanat (21-keyed xylophone), khawng vong (gong circle of 17 pots), and sing (bronze cymbals). Tracks 6 and 7 are also of a Thai song accompanied by traditional classical instruments from Laos. More specific to Laos itself is the recording of the khene, or bamboo mount organ, accompanying repartee (alternating) lam singing on track 9 and the khap singing accompanied by the two-string coconut fiddle so u on tracks 14 and 20.[10]

Cambodia

The remaining four tracks on this disc are of music from Cambodia. On track 2, we hear Cambodian village music, often played on string instruments by “land-mine musicians.”[11] Track 5 is of a Cambodian high monk, or khruba, singing an offering song in the Khmer language, while on track 13, we hear a female Khmer vocalist singing a medley of Thai, Western, and Cambodian songs with a Western-style brass band. This recording reflects the practice of copying the brass bands that came over with European and American delegations. The final example of Cambodian music on track 21 is of a mohori ensemble (traditional Khmer ensemble) playing a long entertainment piece.[12]

Disc B: Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand

In many ways, Disc B is an extension of Disc A, as this second CD features selections of music from Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam (some by the same ensembles), but also includes a few recordings from Thailand. Throughout this disc we see many of the 78 rpm labels mentioned on Disc A, but are also introduced to a number of local Thai labels and several recordings from Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia made at the 1931 Paris Exposition Coloniale Internationale, a sort of world’s fair to promote and celebrate colonialism (125).

Cambodia

This disc includes five more selections from Cambodia. Track 1 is of the same group of village musicians heard on Disc A, although here they are playing “Phleng Boran,” an “Old Song” commonly used for weddings. Beyond this small duplication, this disc offers a range of new experiences. For example, one of the recordings made by the Musée’s Phonothéque Nationale label in conjunction with the Pathé label as part of the 1931 Paris Exposition Coloniale Internationale is of Khmer classical music and can be found on track 7. This recording sounds strikingly similar to Thai music given that it employs similar instruments and follows Thai conventions; however, the track notes are especially helpful for delineating major differences between the two styles. The disc also features Khmer classical music accompanying female vocal singers performing an unspecified theater piece on track 10 and another village-like string ensemble accompanying repartee singing between a male and female performer on track 15. Surprisingly, the liner notes for both of these recordings were written based on speculation, but this is inevitable when dealing with such an antiquated format as the 78 rpm. The most unique Cambodian recording can be found on track 8 featuring a male singer accompanying himself on the long-necked lute chapey singing Cambodian chrieng, a form of epic storytelling ideal for conveying didactic texts to influence public opinion.

Laos

Several of the selection from Laos are quite similar to tracks found on Disc A, for example, the Buddhist “preaching” (monks may not sing) on tracks 9 and 17, the lam repartee singing with khene on track 13, and the khap singing with khene on track 4 The Ensemble of the Governor of Vientiane is again heard on track 20 as it accompanies singers performing poetry from the epic drama “Inao” (taken from the Javanese Panji Tales).[13] What I did find particularly noteworthy on this disc is another recording of the khap style of singing made during the 1931 Paris Exposition Coloniale Internationale on track 5.

Vietnam

Again, several of the recordings from Vietnam on this disc are of the same genre heard on Disc A. For example, one can hear more hát ả đào on track 2, vọng cổ on track 18, and the Chinese influenced huế instrumental music playing a cố bản, or “ancient composition,” on track 16. Having also been under French colonial rule, Vietnam was represented at the 1931 Paris Exposition Coloniale Internationale and has a 78rpm recording included here on track 6. The tune being performed by the small Vietnamese group, “Chant de Bateliers,” or “Song of the Boatmen,” is of vigil music that is typically played during funerary rights and refers to the mythical boatmen who help the deceased’s soul journey to the afterworld (129). Musical rituals like this one have largely disappeared in Vietnam following years of campaigns by the communist government in the north to destroy superstition and “wasteful” funerary rights. This recording thus preserves an almost extinct musical past and is a testament to the profound impact that social and political initiatives have had on Vietnamese music.

Thailand

One of the first pieces of Thai music heard on this disc (track 3) is of a traditional Thai piphat ensemble, which is labeled incorrectly on the original recording as “xylophone solo” (119).[14] Although this is an ignorant ethnocentric labeling, this selection is thought to be one of the earliest recordings of Siamese music.[15] Track 11 is also particularly interesting, as it is a recording of the Chaozhou Opera, which flourished for a time in Bangkok as Chinese immigrants became wealthy and cultivated their own art forms.[16] What I like about the selections found here is that they span a number of genres. Tracks 21 and 22 are of traditional mahori ensembles (Thai classical music played by females in the court) accompanying a bai sri sukhawn ceremony to call back one’s spirit, whereas tracks 12, 14, and 19 showcase various forms of soft and hard mallet Thai classical piphat music accompanying dance, singing, and the wai khru ritual (a ritual expressing appreciation for one’s teachers).[17] Other genres include the lam klawn repartee singing with khene of northern Thailand on track 13 (demonstrating a connection to Laos) and a recording of ramwong singing, one of the predecessors to the popular luk thung genre (track 23) performed by famous luk thung singer Phloen Phromdaen (162).[18]

Disc C: Thailand, Burma

Thailand

Disc C includes another eight tracks from Thailand along with sixteen tracks from Burma. On three of the tracks from Thailand, one can get a sense of Thailand’s efforts to maintain their independence from colonial rule and invoke a sense of modernization through Westernization.[19] For example, a vibraphone substitutes for the ranat ek in a piphat mon ensemble on track 6. As speculated in the liner notes, the use of this instrument represents how Western percussion instruments were adopted when “traditional” activities (like classical music and sitting on the floor) were banned in the name of modernizing the country (178). The recording of the Thai Royal Page Military Brass Band on track 8 and the mandolin made to sound Thai on track 11 also point to the Thai adaptation of Western music.[20]

The traditional music of the piphat mon on tracks 2 and 6 is a style adopted from the immigrant Mon who escaped from Burma and settled in central Thailand during the wars in the 18th century, while on track 13 one can hear the influence of royals from Laos who settled in Bangkok in the recording of a khene ensemble and singer.[21] Track 3 offers a solo on the ranat ek, a 21-bar hardwood (or bamboo) xylophone, and track 10 is one of the oldest extant recordings of piphat music (made in 1910 by Gramophone). Track 17 is also noteworthy in this regard, as the ban doh drum heard in the piphat ensemble of this example, is now obsolete.

Burma

Given that Burma did not officially change its name to Myanmar until the 1990s, the sixteen recordings from this region are categorized as music from Burma. I found these selections quite fascinating, especially the prevalent use of the piano, or sandaya, on tracks 1, 7, 15, 18, 20, 21, 22, and 24. The piano, brought by the British in the 1800s, was adopted by the Burmese court in the 1870s and popularized by applying Burmese finger playing techniques to the accompaniment of the hsaing waing gong percussion ensemble (171).[22] Other examples featuring the Burmese hsaing waing ensemble include a popular song sung by Ma Tin Aye on track 12 and a song about the eight virtues of the Mandalay king on track 16. In these recordings, the singer’s voice evokes yearning, or lunsaya, and demonstrates ayatha, or Burmese aesthetic nuance (187, 192). Several of the other recordings on this disc (tracks 5, 7, 14, 18, 20 and 23) are of yodaya, a Mahagita style song with Thai characteristics, accompanied by various instruments such as the saung gauk (Burmese harp), the sandaya, or a small waing (gong) ensemble.[23] The muted sound of the saung gauk with silk strings as it accompanies ya du singing, a form of half-spoken half-sung poetic recitation, can be found on track 9.

Theater and cinema were extremely important during the 78rpm era, as, unlike other Southeast Asian countries, Burma’s local record industry grew from its cinema (201). This is demonstrated through a the song from the movie “Miss Whiskey” heard on track 21, produced by the British Burma Film Company. A ngyeint, a theater form that developed in the 1800s, also became a source for musical recordings and is represented on tracks 4 and 5. Many famous Burmese musicians and composers were a ngyeint performers, such as Ma Kyi Aung, who is known to be the first female popular recording artist in Burma. She is accompanied by slide guitar and traditional tayaw (horn violin) on track 19.

Disc D: Malaysia/Singapore, Indonesia

Malaysia/ Singapore

The final disc of this collection features recordings of music from Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Seven out of the eight tracks are from Singapore and one track (track 19), is of a love song recorded at Radio Sabah in Sabah, Malaysia. The Malaysia/Singapore selections are a testament to Singapore’s diversity, ranging from peranakan (Chinese who have assimilated Malay culture) music on tracks 3, 7, and 11, to the syncretic bangsawan theater (a type of commercial theater that developed at the turn of the 20th century and mixed Malay, Chinese, European, Indian, and Arabic influences) heard on tracks 9, 16, and 20 (217, 256). A recording of a gambus ensemble (a pear-shaped lute similar to the ud) on track 14 also suggests a connection to Islam and the Middle East and is commonly used in bangsawan plays.

Indonesia

The gambus could also be found in Indonesia during this time and is played heterophonically with an accordion, violin, bass, and rebana (frame drum) on track 21. Two tracks from the 1928 Odeon recordings from Bali can be found on this disc and include gender wayang (music to accompany Balinese shadow theater) on track 6 and the janger dance on track 15.[24] Track 2 is of a song from the Javanese stambul theater titled “Miss Riboet,” in which wood block and piano are used to create the aesthetics of a lagoe tionghoa, or Chinese song. On track 18, one can hear the influence of the large Chinese communities living around Jakarta through a recording of gambang kromong, music mixing Chinese and native Indonesian elements (flute, fiddle, and kromong gong chime).[25]

In addition to some of the syncretic styles heard on this disc, one can also find great examples of central Javanese gamelan in soft style on track 17 and in loud style on track 13. Tracks 1 and 12 showcase the Sundanese gamelan saléndro accompanying vocalists (sinden) singing a lagu kawih, or Sundanese tune, and track 8 is of tembang Sunda, a poetic song form accompanied by kecapi zither and suling (bamboo flute).[26] Another interesting feature of this disc are the ethnographic recordings from the Folkways ethnic series of Batak music in north Sumatra on track 4 and the Minangkabau music of West Sumatra on track 5. These selections are complimented nicely by a Sumatran song recorded by Dutch ethnomusicologist Bernard IJzerdraat on track 10.

Reflections

While this is the first collection to present 78 rpm recordings from across Southeast Asia, many genres of music were purposely not included and many were never recorded in the first place. Nevertheless, this collection should not be dismissed, as it was not intended to be a survey of Southeast Asian music, nor was it meant to be representative of the wide variety of music recorded during this time. Instead, the value in this collection lies in some of the obscure and obsolete styles captured on the medium of 78 rpm records, which was David Murray’s (the work’s main contributor) original intent (13).[27] It was surprising to find that nearly 76% of the recordings were from mainland Southeast Asia, whereas only 24% were from maritime Southeast Asia.[28] While I understand that the 78rpm genre limits the selection of music that can be represented, I was surprised that recordings from the Philippines and other parts of island Southeast Asia were not included. This collection left me wondering whether 78 rpm recordings were ever made in other Southeast Asian locations and questioning why there was such a focus on mainland Southeast Asia. Even so, the scholarship on the record industry and the musical cultures of each country make this a great supplement for a course on Southeast Asian music, and given its mainland focus, I could see this collection being a great complement to an educational text such as Gavin Douglas’s Music in Mainland Southeast Asia: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture (2010).[29]

Although this work does have educational appeal, the design and content of the collection suggest that it does not strive to be a scholarly edition. All of the photos were absolutely stunning, but many were not given a description and some seemed arbitrarily placed throughout the book with seemingly no connection to the track being described. Foreign terms were not always defined upon first use and there was no glossary, meaning that this collection might best belong in the hands of someone who has a preliminary knowledge of the Southeast Asian music. The focus on aesthetic appeal and presentation of succinct and digestible information makes me think that this is more geared toward leisurely consumption. In addition to being an educational supplement, I really see this beautiful set placed on a bookshelf or coffee table of someone from Southeast Asia living in the diaspora, where it represents a tangible piece of their heritage and cultural history. Overall, Longing for the Past: The 78 rpm Era in Southeast Asia preserves an important musical and historical past and should be considered a rare and useful resource for scholars of Southeast Asian music and history.

Notes

[1] Cải lương, or “reformed theater,” was the main genre of music being recorded in the 78 rpm format in the 1940s. These recordings usually consisted of a type of aria vọng cổ (a musical form that allows much improvisation and translates to mean “longing for the past”), which was the single most important musical work of 20th century Vietnam (67). It seems apropos that this collection be titled as such considering the historical connection between this aria form and the prevalence of recordings in the 78 rpm format.

[2] David Murray, who spearheaded this project, maintains a blog on 78 rpm music and has produced several CDs. Terry Miller is a renowned specialist of Mainland Southeast Asia (Thai and Laos) and Jason Gibbs specializes in Vietnamese music and culture. Kit Young writes expertly on Burmese piano (sandaya) styles and her expertise is well represented in this work. David Harnish, expert of Indonesian music, covers the eleven tracks on Indonesia found on Disc D, while Ethnomusicologist Sooi Beng Tan offers her expertise on the bangsawan theater in Malaysia.

[3] For example, during the time that these recordings were made, Malaysia and Singapore were not separate, so the recordings are organized as Malaysia/Singapore. Similarly, Myanmar was still called Burma at the time, so Burma is the label used to organize the recordings from this region.

[4] At the time that these recordings were made, these three countries were known as French Indochina.

[5] As mentioned above, vọng cổ arias came from the cải lương, or “reformed theater,” which was the main genre of music being recorded in the 78 rpm format in the 1940s.

[6] The Chinese captured the Vietnamese Red River basin in 111 BCE and retained control until 938 AD, resulting in is a strong Chinese influence on Vietnamese arts that is present to this day (45).

[7] Ca trù, also known as hát ả đào or hát nói, is northern Vietnamese dance chamber music genre featuring a female vocalist, an instrumentalist who plays the đàn đáy lute, and a drummer (Norton 2014:166). This form of sung poetry was originally performed for the aristocracy and the courts, but later moved into the homes of mandarins, where it became known as “singing for entertainment” and expressed social discontent and anti-Confucian thought (108). For more on ca trù, its history, and its nomination for inscription on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list, see Norton 2014.

[8] South Asian elements in Vietnamese music come from long-term contact with the Cham and Khmer kingdoms (45).

[9] There is speculation as to where the Laos recordings where made. It is believed that many were made by visiting musicians from Laos in Vietnam when the Victor recording company made one of their expeditions there. Therefore, it is very likely that no 78rpm records were ever recorded in Laos itself.

[10] Singing in southern Laos is called lam, whereas singing in the north is called khap (Miller 2013:97).

[11] Although the Khmer Rouge led to an estimated 80% of Cambodia’s musicians and dancers to flee or be killed, the musical culture has been rebuilt, and those who have been injured by the still landmine-sewn country often play at various temples to sustain themselves.

[12] The nonstandard ensemble in this recording uses of xylophones (roneat ek and the roneat thom), a gong circle (kong thom), and small cymbals (chhing). The make up of this ensemble points to a clear connection with Thai music and the larger gong culture of Southeast Asia.

[13] The Panji tales are stories of a legendary prince in east Java, which, along with the Ramayana and the Mahabharata make up the basis for much of the poetry and stories of the shadow puppet theater (wayang kulit). See Brandon 1970 for more information.

[14] Piphat is a Thai classical music ensemble usually consisting of five instruments: ranat ek (higher xylophone), khawng wong yai (lower gong circle), pi nai (quadruple reed aerophone), drum, and ching (small bronze cymbals used to mark the cyclic meter) (185).

[15] Thailand was known as Siam until 1939 (52).

[16] This recording was produced on the local label Tiger, which seems to have only recorded folk operas of Chaozhou immigrantsThis, in and of itself, is quite fascinating, and could potentially be a great research project for someone interested in Chinese migration to Thailand and the development of specialized record labels for Chinese arts to be cultivated in the diaspora.

[17] See Wong (2001) for more information on the Thai wai khru ritual.

[18] Luk Thung, or “songs of the fields,” is a genre of Thai popular music expressing the lives of ordinary people. It was derived from luk krung, or “songs of the city,” a kind of ballroom dance music sung with Thai poetry (54).

[19] Siam used modernization to prevent ideas of “manifest destiny” and possible European efforts to take over the country and “civilize” it. To this end, a Thai symphony orchestra was even developed (53).

[20] Western influence came from the European and American delegations and their brass bands that visited Siam in the early 19th century. Siamese musicians learned to play these instruments and formed bands for the Thai court and military (180).

[21] Again this demonstrates that although Thailand was and is defined by officially recognized borders, these boundaries are somewhat arbitrary when it comes to Thai music, as a number of foreign cultural influences can be found in the genre.

[22] A hsaing waing ensemble includes a pat waing (21 pitched drums), kyi waing, (small bronze gongs in a circular frame), maun (brass gong set), and kyauk lon bat (drums, gong, clapper) (187).

[23] The Mahagita is the complete body of Burmese classical songs, meaning “Great Song” or “Royal Song.”

[24] The janger dance is a type of dance where young men and women use call and response song, which grew in response to the stambul theater (theater derived from Chinese-Malay Opera) in Java. For more on dance and drama in Bali, see Dibia and Ballinger 2004.

[25] The prevalence of Chinese influenced music and arts in Indonesia during this time remain important pieces of history given the brutal persecution and killing of many Chinese during the communist purges in the 1960s.

[26] Gamelan saléndro is an ensemble of metallophones, gong chimes (bonang), gongs, drums, a bowed spiked lute (rebab), xylophone (gambang), and vocalist (235).

[27] When comparing this work to similar works of its kind, there seems to be an emerging trend to organize and develop thematic projects from the pool of Southeast Asian 78 rpm material. For example, Balinese music scholar Edward Herbst has spent a number of years on a restoration and repatriation project titled Bali 1928 (2015), and produced five extensive, book-length essays (nearly 600 pages) and 5 CDs with Arbiter records. Herbst focused on the Odeon and Beka recordings of various forms of Balinese music. This collection also features two recordings from Bali on the Odeon label, but also draws from a number of early colonial record companies and local labels in its broad scale approach to represent Southeast Asia.

[28] In terms of maritime Southeast Asia, the collection covers music from Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, but is mostly focused on Indonesia and Singapore, as there is only one recording from Malaysia that is not labeled Malaysia/Singapore.

[29] This is an educational text written as part of the Global Music Series published by Oxford University Press. Douglas devotes a great deal of time to exploring how geographical boundaries do not necessarily denote musical boundaries, and several of the recordings found in this collection could be useful in driving home this point.

References

Brandon, James R. 1967. Theater in Southeast Asia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

_______. 1970. On Thrones of Gold: Three Javanese Shadow Plays. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dibia, I Wayan, and Rucina Ballinger. 2004. Balinese Dance, Drama and Music: A Guide to the Performing Arts of Bali. Singapore: Periplus.

Douglas, Gavin. 2010. Music in Mainland Southeast Asia: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Herbst, Edward. 2015. Bali 1928 (5 CDs and essays). New York: Arbiter of Cultural Traditions.

Murray, David, ed. 2014. Longing for the Past: The 78 rpm Era in Southeast Asia. Atlanta: Dust-to-Digital.

Norton, Barley. 2014. “Music Revival, Ca Trù Ontologies, and Intangible Cultural Heritage in Vietnam.” In The Oxford Handbook of Music Revival, edited by Caroline Bithell and Juniper Hill, 160-182. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wong, Deborah. 2001. Sounding the Center: History and Aesthetics in Thai Buddhist Performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Biography

Meghan Hynson received her PhD in Ethnomusicology from the University of California, Los Angeles in 2015 and is now a Visiting Assistant Professor of Ethnomusicology at Duquesne University. Her research focuses on the performing arts of Indonesia, in particular, music and ritual in Bali and the use of angklung in music education and cultural diplomacy in West Java. Meghan’s current research projects include the Balinese wayang sapuh leger ritual from Mas Village, Gianyar; religiosity and syncretism in the Balinese “Call to Prayer” (Tri Sandhya); and commoditization and change in the DVD culture of modern Balinese shadow puppet theater.

E-mail: meghanhynson@gmail.com