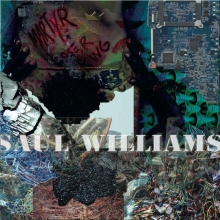

Review | We, the Multitude of Losers: Saul Williams’ Martyr Loser King

We, the Multitude of Losers: Saul Williams’ Martyr Loser King

Reviewed by Ben Dumbauld / City University of New York

For the so-called millennial generation, the term “loser” has gone through an interesting sociolinguistic evolution. Being born in the early 1980s I am on the senior end of the millennials, but I remember a time when the accusation of being a loser deeply pierced one’s sense of self-worth. “You’re such a loser” usually meant that joke I told didn’t land, or that I failed to correctly grasp an imminently important piece of playground cultural capital. In grade school, no one wanted to be a loser.

And then in the early 90s, “loser” lost much of its acerbity. Grunge made social apathy a source of pride, and the refusal to be co-opted into the mainstream became a stance of distinction. By the release of Beck’s “Loser” and Radiohead’s “Creep,” the loser’s change of status was all but complete: no longer an outcast, but an iconoclast. The precedent Beck established for the loser as charmingly quirky rather than socially unacceptable has today firmly entrenched itself into the indie music world: one needs only look at Arcade Fire’s orchestration and fashion choices.

In Martyr Loser King, rapper/poet/actor Saul Williams provides us with a new type of loser, a 21st century loser.[i] A loser not defined by a choice of cultural distinction, but by economic circumstances. A loser at the sum-zero game of international late capitalism. For my generation, the inheritors of the Reagan, Bush, and Clinton neoliberal legacy, this game was already well established: through anti-drug programs in grade school, mandatory high school “leadership camps,” and inspirational TED Talks we were told that the winning path is one of embracing our creativity, cultivating our leadership abilities, and spurring innovation. We learn now that such creativity is often only valid inasmuch as it aligns itself with neoliberal virtues. Manipulate the game to your advantage and you are rewarded; imagine a new game and you are branded unrealistic. This is the political battle of our generation: attempts to change the modes of domination in language are branded overly “politically correct”; elucidating injustices that have gone previously unrecognized turns one into a bleeding-heart “Social Justice Warrior”; demanding a society that takes care of its citizens leads to accusations of entitlement. Our response to this back and forth, in which calls for a more equitable world are met with accusations of activist character flaws and unrealistic thinking, is perhaps most eloquently stated in Williams’ mantra, repeated ad infinitum, in “All Coltrane Solos at Once”: “Fuck you, understand me.”

Beyond this, Williams offers no easy solutions to this impasse. There are no time and space travelling messiah figures in this afrofuturist epic, ready to unite the believers and enlighten the non-believers. Rather, the protagonist in Martyr Loser King is the biggest loser of all: an invisible, peripheral coltan miner from Burundi. And while the solutions aren’t forthcoming throughout the album, Williams pinpoints the paradoxical nature of the problems we all live with, from gender identity, global inequality, police brutality, postcolonial history, and the lingering legacy of slavery.

By the fifth track one of the most prominent paradoxes emerges: technology, and its potential to both liberate and enslave. Titled “The Bear/Coltan as Cotton,” it is at this point that our protagonist shifts from being a nameless miner to a hacker/“terrorist,” tapping into the technology that feeds off of the very minerals he extracts. Coltan is indeed the cotton of the digital world, a material globally ubiquitous, necessary, and completely derived from what is essentially slave labor. This idea continues in the subsequent track “Burundi,” where Williams acknowledges that it is “Factories in China and coltan from the Congo” that allows the radical idea to spread virally over the internet. Later in “Roach Eggs” the protagonist realizes his impact: “Woke up in the morning/High off the internet/Five million followers/Now on the internet/I own the internet.” Is this wishful thinking? Can one’s popularity on the internet be more powerful than the Silicon Valley speculators and communications monopolies that control it? Can the master’s tools dismantle the master’s house in this new digital age?

Musically, Williams and his partner Justin Warfield draw from the afrofuturist lineage, which is made abundantly clear in the opening moments of the album: a continued repetition of the vocal sample “into the promised land,” caked in delay and surrounded by sci-fi sounds. From there the album mixes various central African samples with synth basses, ethereal pads, driving drum loops, and digitally glitched-out vocals. “The Noise Came from Here” begins with a sample of a Twa choir, which continues throughout the song. “Down for Some Ignorance” is based around a repetitive mbira riff, while the piano sample in “Horn of the Clock-Bike” sooner evokes kora ostinatos than anything in the western cannon. The effect of these combinations is the creation of a sonic mise-en-scène that evokes an African postcoloniality, rich in tradition and tragedy, and digitally wired into a global network.

So what, as scholars and teachers, can we draw from this album? It is clear from the outset that Williams is offering no favors to education here—throughout the work educators are more often painted as an essential part of the hegemonic power structure than a means to evade or alter it. In “Ashes,” Williams spits “History tries it’s best to keep us kneeling,” signifying both the oppressive nature of history as such, and the subtle oppression of History as taught in school, which already disenfranchises the dominated class by presenting the world in terms of strength and weakness, of oppressors and victims, of winners and losers. Williams drives this point home in “Burundi”: “Virus, I’m a virus, I’m a virus in your system/Fuck your history teacher, bitch, I’ve never been a victim/I’m just a witness, Hitler can come get this/Rabbis in Ramallah throwing burkas on these bitches.” Here Williams displays his talent at expanding the braggadocio central to the rap genre into a model of revolutionary consciousness. Despite the immense structures of power working against him, the protagonist of Martyr Loser King refuses to consider himself a victim of global injustice, but a witness to global injustice. In a discipline itself tied to the history of colonialism, ethnomusicologists might further take up Williams’ call and think seriously about conceptualizing the global disenfranchised not as victims, but as witnesses, first-hand witnesses to a global structure where only too often the One Percent profit through the exploitation of the Ninety-nine. Thus begins a History written by the losers—and perhaps a future.

Note:

[i] Saul Williams’ Martyr Loser King was released January 29th 2016 on Fader Label. A companion graphic novel will be release later this year on First Second Books.