Stormzy vs. Mozart: Moral Panic against UK Rap in the British Media

“The British media just got me beefing Mozart. I do not want to beef Mozart. Mozart is my guy. Peace.” Stormzy

Arguably one of the most prolific figures in UK grime, Stormzy has become a British household name in the last five years. In 2017, Stormzy became the most streamed grime artist on Spotify (Riley 2017: 20) and was referenced as listeners’ favorite grime artist by 47% of participants in Ticketmaster’s study “State of Play: Grime” (Ibid.: 24). Grime, however, is rarely afforded just treatment in mainstream media. Stormzy has featured prominently in headlines for his support of the Labour party, speaking out about the injustices of the Grenfell inquiry and for using his platform to discuss racism in the UK.[i] While many have raised valid concerns regarding Stormzy’s “grime credentials” given his lack of pirate radio experience (de Lacey 2019: 281), Jessica Perera notes that Stormzy is undeniably part of a broader grime youth culture in the UK that “encapsulates the lived experience of young metropolitan Black working-class life”(Perera 2018: 87). Therefore, Stormzy epitomizes values of grime culture and is more broadly viewed as epitomizing the genre by fans and non-fans alike, regardless of his authenticity credentials.

The “Stormzy vs Mozart” moral panic emerged from the charity Youth Music publishing a report on their project “Exchanging Notes.” This was a four-year long initiative that worked with young people with low attainment at school, dramatically improving students’ attendance and engagement in the classroom.[ii] Youth Music CEO Matt Griffiths wrote an open letter to Nick Gibb MP after the report was published, calling for “a music curriculum which reflect[s] [the students’] diverse interests and existing lives in music” (Griffiths 2019). There is no explicit mention of Stormzy or Mozart in the report or letter, but there is frequent allusion to the idea that current music curricula taught in UK state schools do not sufficiently represent musics with which young people engage.

The originator of this moral panic is unknown, but this idea was entirely a media creation. The Telegraph (Swerling 2019) and Sky News (Sky News 2019) categorically state that Youth Music believes Stormzy should “replace” Mozart, whereas The Guardian’s report (Weale 2019) emphasizes the idea of more “focus” on Stormzy. Good Morning Britain’s debate format (Good Morning Britain 2019) allowed for some more nuance. Black journalist Afua Adom suggests that the curriculum should be updated to include “modern day Mozarts,” while white classical musician Camilla Kerslake regards getting rid of classical music as “unhelpful,” citing the popular claim that Mozart’s music improves students’ intelligence. Moreover, Adom emphasizes the need for inclusion of a variety of Black musical forms in music curricula, to ensure that students engage with political, sociological and economic issues entwined with these genres. Overall, these headlines were short-lived and the hysteria surrounding this report lasted a few days. The moral panic continued, however, in the form of extensive blog posts and social media rebuttals throughout 2019.

Moral Panics and Responses

Based on Stuart Hall’s definition of “moral panic,” we can understand the extensive coverage of this story throughout 2019 as “out of proportion” to the actual “threat offered” (i.e., diversifying curricula, rather than full elimination of classical music from the classroom).[iii] The “experts” who offered their opinions in extensive responses were mostly not associated with grime or the UK music industry, but based their opinions on broad-brushstroke stereotypes surrounding rap music by taking the headlines at face value. Although media responses varied, many spoke “with one voice” about the “threat” of Stormzy replacing Mozart. Moreover, the responses which perceived Youth Music’s report negatively appeared threatened by the “novelty” of Black music on the curriculum, and implied there would be a “sudden and dramatic increase” of deplorable behavior in school (despite “Exchanging Notes” conveying the opposite).

Lengthier responses fell into two camps. Some decried the media coverage for its essentialist tone, whereas responses from conservative critics concerned themselves with a supposed intellectual impact on British children. Musician Michelle Hames remained rational, outlining that nowhere in the report are the names Stormzy or Mozart mentioned, nor is the idea of eradicating classical music from school curricula part of Youth Music’s agenda (James 2019). Max Wheeler’s blog was published by Youth Music on their website, explaining how this clickbait-style coverage and headlining “is almost always used to frame curriculum design as a binary conflict between A and B; mutually exclusive and antithetical on every level” (Wheeler 2019).

The politically conservative responses, however, take headlines word for word. Educator Calvin Robinson makes salient points regarding the limited amount of space on curricula, meaning “every addition means a subtraction somewhere” (Robinson 2019). Rebutting Youth Music’s suggestions, Robinson cites canonical longevity to justify that Mozart is more worthy of study, as well as broader ideas of aesthetic beauty based in Western art music. He states, “There’s a level of beauty, call it subjective, in a Mozart concerto that simply cannot be measured against Stormzy’s ‘Tell my man shut up’” (ibid.). These literal readings of rap practices are common in conservative criticisms, as Justin Williams notes, critics of hip hop do not take heed of how rappers adopt hyperbolic roles in their musical performances, “even if their own persona is loosely based on real life” (Williams 2017: 97). The most prolonged outcry came from Katharine Birbalsingh: a conservative headmistress of the Michaela Community School, who often speaks out in British mainstream media on political issues in education. In The Times in December 2019, Birbalsingh heavily criticized the perceived abundance of swearing in grime music, stating that teaching this music would be “encouraging Black self-hatred” (Griffiths 2020) among students. She elaborated further on Twitter, describing all rap music as “revolting” (Birbalsingh 2019a) and exclaiming that “the establishment” (Birbalsingh 2019b) should favor Mozart over Stormzy due to the (assumed) bad language of grime.

None of these extensive responses nor the initial media outcry address the current school music curricula in detail. There is an implicit assumption across the coverage of this moral panic that no popular music is taught in schools, with an overemphasis on Western classical music; which is assumed to be at odds with the musics that students really like and want to study. To assess the validity of these assumptions, the next section uses three contemporary GCSE curricula syllabi to expand on broader implications regarding the implicit values of music education in Britain.[iv]

Addressing the Curriculum and Broader Implications

The decline of music education in British state schools is semi-regularly covered in mainstream news. Two months prior to this moral panic, BBC News reported that state schools in England have seen a 21% decrease in music provisions in the last five years, while access to music in independent schools rose by 7% (Savage 2019). Moral panics with hyperbolic responses regarding the decline of state school music education have haunted mainstream media for some time. In 2017, journalist Charlotte Gill suggested that less emphasis on reading Western music notation could encourage more students to take up music in state schools (Gill 2017). This caused outcry among (mostly classical) musicians, who penned a letter in response strongly objecting to this idea (Pace 2017). It is clear from this example that the (classical) musicians’ opinion on music education is that “dumbing down” the current curricula (i.e., less emphasis on reading Western notation) would be a detriment to students. Moreover, there are implicit assumptions in this outcry regarding what should be part of the process of mainstreaming and institutionalization via the curriculum. In other words, UK rap is currently very successful in mainstream listening (i.e., UK music charts), but the “mainstream” or institutional genre/style of music education is still firmly entrenched in classical music.

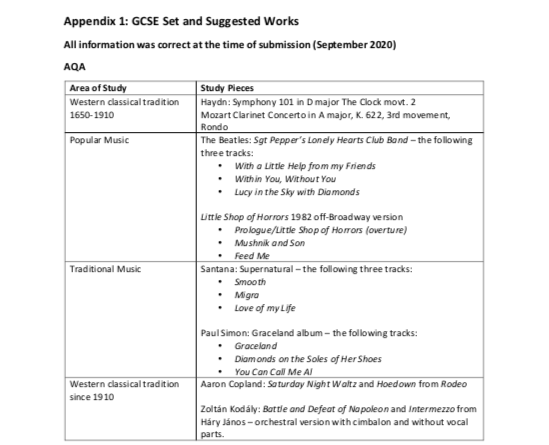

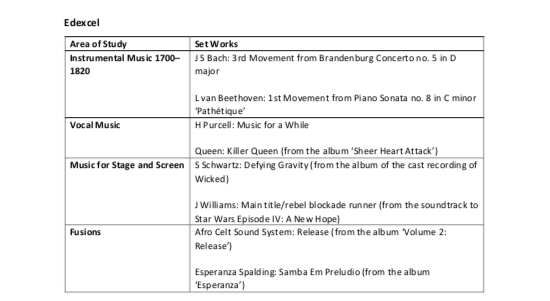

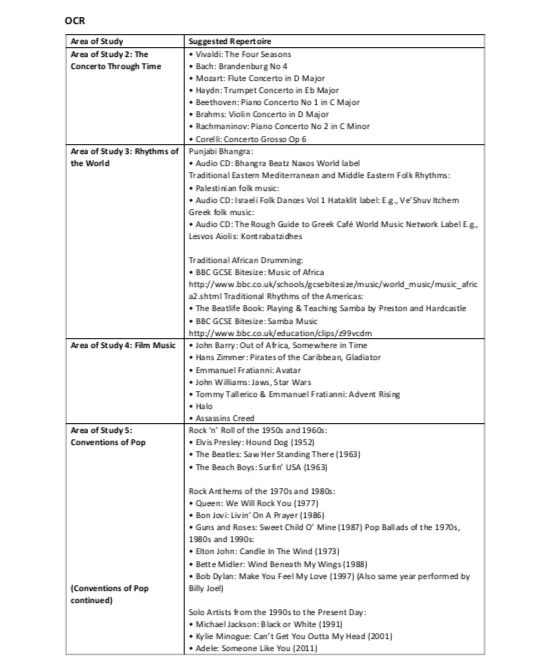

Youth Music’s study claims that popular music genres are not taught widely enough in state schools (Griffiths et al. 2019). Copies of the set/suggested works for the exam boards Edexcel, AQA and OCR are provided in appendix 1.[v] While all three exam boards include set/suggested works from popular genres, these are overwhelmingly outnumbered by Western art music. Moreover, most of the popular music set/suggested works are by white male artists such as The Beatles, Paul Simon and Bob Dylan, neglecting the vast contribution of Black artists to anglophone popular music. None of the set/suggested works include any rap related genres. Jazz features in all three specifications, but Black diasporic genres stemming from Jamaican sound system culture, like most UK rap genres, are absent. While some exam boards include an unheard listening and appraisal component in which UK rap could feature, these rigid lists of suggested works hold significant weight in UK curricula and dictate the repertoire used in classroom teaching. If no UK rap music is suggested by the exam board, why would teachers be inclined to teach it?

There is a broader issue here regarding identity, musicianship and values embedded in music education. On the British television program Good Morning Britain, grime MC Yizzy noted that he mostly learnt classical music at school through a very limited and uncreative curriculum. On a personal level, as a classically-trained musician who has taken Edexcel GCSE and A level music in the last 6 years, I felt the need to conform my music tastes to be more classically-oriented in order to succeed in British “classroom music” and be perceived by educators as a “real” and “credible” musician. In other words, I hid my love of hip hop and rediscovered it at university. Anna Bull’s extensive research on this topic notes that many young classical musicians in her study felt the need to adopt a classical music “identity” in order to participate in music hub projects and ensembles (Bull 2019): something which I undoubtedly did in order to achieve good grades and go on to study music at university. An encouraging finding from the “Exchanging Notes” report, however, was that the program allowed students to develop “new music-related identities,” (Griffiths et al. 2019: 23) that they would take forward into their future as musicians. Students developed unique musical identities based on their interests, rather than molding a different one to succeed in classroom music. Although Grime music can be framed as possessing “middle class values related to education, entrepreneurialism (legally) and not getting involved in street violence,” (Ilan 2012: 47) it is still viewed as a “dangerous” form that is at odds with the middle-class values of music education based in Victorian pedagogy, which privileges Western classical music as its “mainstream” rather than popular music (Bull 2019).

Conclusion

The absence of any Black diasporic genres with roots in Jamaican sound system culture in music curricula evokes racist value judgments regarding UK rap music and its place in the education of young musicians (i.e., that it is not worthy of formal study). According to Spencer Swain, media discourses on grime and other UK rap genres have led to many arguing that these musics are “deviant, and uncivilized, particularly in comparison to more acceptable tropes such as pop and classical music” (Swain 2018: 482). More broadly speaking, this moral panic outlines Paul Gilroy’s assertion that while Black people are represented to some extent in British politics and culture, these representations are “precarious constructions, discursive figures which obscure and mystify deeper relationships” (Gilroy 2002: 201).

Most of the conservative commentators were seemingly apathetic towards British music education before this moral panic, until there was a suggestion that Stormzy might be on the curriculum in favor of the musical “genius” of Mozart. Regarding processes of mainstreaming and institutionalization, this highlights very different ideals that are held up in music education as opposed to mainstream music listening (e.g., the UK music charts, in which UK rap has performed consistently well in the last ten years).

The three GCSE syllabi demonstrate how music education in the UK is an overwhelmingly white affair, that privileges reading and appraising Western notation, and learning only of the contribution of white artists to popular music. Furthermore, the “set work” approach, which compartmentalizes the study of all music ever into around 12 pieces, greatly restricts the scope of musics that can be covered on any given syllabus. As long as these restrictive curriculum structures for music GCSE and A level remain in place, there will always be a divide between the mainstreaming and institutionalization of Black music in popular culture and what is taught in music education. Furthermore, conservative educators with public voices, using their platforms to decry Grime, are acting as further gatekeepers to the syllabi; even those who are not music teachers.

Conversely, the “Stormzy vs Mozart” moral panic poses valuable questions concerning music education. What kind of musicians are employed to teach British students? Who is writing the syllabi? What genres and practices do we believe are necessary to study in order to become a musician? What value judgments are currently inscribed into these teachings? The current GCSE curricula examined here evoke ideas about musics, musicking and musicianship that are assumed and never questioned. Inclusion, discussion and teaching of UK rap genres can allow us to explore these questions more deeply, revealing some of the deeply entrenched prejudices and value judgments embedded into teaching practices and syllabi. Spotlighting rap scenes and musicians can allow for extensive discussion of social issues and the music industry more generally.

References

Primary Sources

AQA. 2020. “3.1 Understanding music.” https://www.aqa.org.uk/subjects/music/gcse/music-8271/subject-content/understanding-music. (accessed 3 September 2020).

Edexcel. 2016. “GCSE (9-1) Music Specification.” https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/GCSE/Music/2016/specification/Specification_GCSE_L1-L2_in_Music.pdf. (accessed 3 September 2020), 50.

Good Morning Britain. 2019. “Should Schools Scrap Mozart for Stormzy? | Good Morning Britain.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHzlRuIlwng. (accessed 15 July 2020).

Griffiths, Matt. 2019. “Open Letter from Matt Griffiths, CEO of Youth Music to The Rt Hon Nick Gibb MP and the DfE Model Music Curriculum Panel.” (accessed online 15 July 2020).

Griffiths Matt et al. 2019. “Exchanging Notes: Research Summary Report.” Youth Music. https://www.youthmusic.org.uk/exchanging-notes. (accessed 15 July 2020).

OCR. 2018.“GCSE (9-1) Specification Music.” https://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/219378-specification-accredited-gcse-music-j536.pdf. (accessed 3 September 2020), 45-46.

Pentreath, Rosie. 2019. “Could Stormzy replace Mozart in the music curriculum?” Classic FM. https://www.classicfm.com/music-news/could-stormzy-replace-mozart-music-curriculum/. (accessed 15 July 2020).

Sky News. 2019. “Stormzy should replace Mozart in UK music classrooms, study says.” Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/stormzy-should-replace-mozart-in-uk-music-classrooms-study-says-11725859. (accessed 15 July 2020).

Swerling, Gabriella. 2019. “Stormzy should be taught in schools instead of Mozart to prevent exclusions, charity urges.” The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/05/21/stormzy-should-taught-schools-instead-mozart-prevent-exclusions/ (accessed 15 July 2020).

Weale, Sally. 2019. “School music lessons should cover hip hop and grime, says charity.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/may/22/school-music-lessons-should-cover-hip-hop-and-grime-says-charity. (accessed 15 July 2020).

Secondary Sources

Birbalsingh, Katharine @Miss_Snuffy. 2019a. Twitter. https://twitter.com/Miss_Snuffy/status/1208897534044917760. (accessed 16 August 2020).

____________________________. 2019b. Twitter, https://twitter.com/Miss_Snuffy/status/1209450465102045184. (accessed 16 August 2020).

Bramwell, Richard and James Butterworth. 2019. ""I Feel English as Fuck": Translocality and the Performance of Alternative Identities through Rap". Ethnic and Racial Studies: Special Issue: Racial Nationalisms: Borders, Refugees and the Cultural Politics of Belonging 42, no. 14: 2510-2527.

Bull, Anna. 2019. Class, Control, and Classical Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Charles, Monique. 2016b. “Grime Central! Subterranean ground-in grit engulfing manicured mainstream Spaces”, in Blackness in Britain, edited by K. Andrews and L. A. Palmer, 80-100. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

de Lacey, Alex. “Level Up: Live Performance and Collective Creativity in Grime Music”. Ph.D.diss., Goldsmiths University of London, 2019.

Dedman, Todd. 2011. “Agency in UK Hip-Hop and Grime Youth Subcultures – Peripherals and Purists”. Journal of Youth Studies 14, no.5: 507–22.

Gill, Charlotte C. 2017. “Music education is now only for the white and the wealthy.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/mar/27/music-lessons-children-white-wealthy. (accessed 16 August 2020).

Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

__________. 2002. There Ain't No Black in the Union Jack the Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. London: Routledge.

Griffiths, Sian. 2019. “Stormzy accused of teaching children self-hatred.” The Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/stormzy-accused-of-teaching-children-self-hatred-j9xfdxhpr. (accessed 15 July 2020).

Hall, Stuart. 2018. “The Social History of a “Moral Panic””, in Policing the Crisis: Mugging, The State, and Law & Order, edited by S. Hall, C. Critcher, T. Jefferson, J. Clarke and B. Roberts, 7-31. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ilan, Jonathan. 2012. “The industry’s the new road’: Crime, commodification and street cultural tropes in UK urban music”. Crime, Media, Culture, 8: 39–55.

James, Michelle. 2019. “Stormzy vs Mozart. “Medium. https://medium.com/@MichellejJames1/stormzy-vs-mozart-6dd8df771be2. (accessed 15 July 2020).

Pace, Ian. 2017. “Response to Charlotte C. Gill article on music and notation – full list of signatories.” WordPress. https://ianpace.wordpress.com/2017/03/30/response-to-charlotte-c-gill-article-on-music-and-notation-full-list-of-signatories/. (accessed 16 August 2020).

Perera, Jessica. 2018. "The Politics of Generation Grime." Race & Class 60, no. 2: 82-93.

Riley, Mykaell. 2017. “State of Play: Grime.” Ticketmaster Blog. http://blog.ticketmaster.co.uk/stateofplay/ grime.pdf. (accessed February 15, 2020).

Robinson, Calvin. 2019. “My pupils need Mozart, not Stormzy. Innit?” Conservative Woman. https://conservativewoman.co.uk/my-pupils-need-mozart-not-stormzy-innit/. (accessed 15 July 2020).

Savage, Mark. 2019. “Music lessons ‘being stripped’ out of schools in England.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-47485240. (accessed 15 July 2020).

Swain, Spencer. 2018. “Grime music and dark leisure: exploring grime, morality and synoptic control”. Annals of Leisure Research, 21:4: 480-492.

Toynbee, Jason. 2002. “Mainstreaming, from hegemonic centre to global networks”, in Popular Music Studies, edited by D. Hesmondhalgh and K. Negus, 149-163. London: New York: Arnold; Distributed in the United States of America by Oxford University Press.

Wheeler, Max. 2019. “Stormzy vs Mozart vs Music Education.” Youth Music. https://network.youthmusic.org.uk/stormzy-vs-mozart-vs-music-education. (accessed 15 July 2020).

Williams, Justin A. 2017. “Rapping Postcoloniality: Akala’s “The Thieves Banquet” and Neocolonial Critique”. Popular Music and Society 40:1: 89-101.

Imogen Lawlor (she/her) is a classical violinist and writer from Reading, currently working in a school doing outreach work. She graduated with distinction from Goldsmiths, University of London with an MA in Popular Music Research in 2020, where her dissertation research focused on processes of mainstreaming in UK rap. She is also an alumna of Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford where she read for a BA(Hons) in music. Imogen cares greatly about music education being accessible to all and has collaborated on EDI initiatives and campaigns with Sound and Music, the Musicians’ Union and the Oxford Music Faculty Athena SWAN – as well as incorporating these values into her own performances, writing and violin practice. She has played for ensembles including the Young Musicians’ Symphony Orchestra, University of London Symphony Orchestra and Oxford University Orchestra to name a few. Her writing can be found in the British Music Collection, Hip Hop Scotland and Vinyl Chapters, for whom she is currently a weekly review contributor.

[i] The Grenfell Tower Fire was a result of cheap flammable cladding on the outside of the 24-storey apartment building. The fire broke out on 14th June 2017, in which 72 people died. Many of the residents of the tower were people of colour and several UK rap artists spoke out about the injustices of this tragedy.

[ii] Nick Gibb is the Conservative Member of Parliament for Bognor Regis and Littlehampton. He is also the Minister for State School Standards.

[iii] “When the official reaction to a person, groups of persons or series of events is out of all proportion to the actual threat offered, when ‘experts’, in the form of police chiefs, the judiciary, politicians and editors perceive the threat in all but identical terms, and appear to talk ‘with one voice’ of rates, diagnoses, prognoses and solutions, when the media representations universally stress ‘sudden and dramatic’ increases (in numbers involved or events) and ‘novelty’, above and beyond that which a sober, realistic appraisal could sustain, then we believe it is appropriate to speak of the beginnings of a moral panic”

[iv] GCSEs (General Certificate of Secondary Education) are academic qualifications taken in the UK (excluding Scotland) in academic Year 11, aged 15/16. Post-16, many choose to take A levels, which are often entry requirements for British universities

[v] These are the exam boards for most GCSE and A level examinations taken in England and Wales.