Through the Lens of a Baroque Opera: Gender/Sexuality Then and Now

William Faulkner once famously wrote, "The past is never dead. It's not even past" (1950:73). This idea that the past is always present is at the heart of this paper. Nothing is created in a vacuum, and while the cultural constructs of historical eras differ vastly from those of the present, they crucially inform the here and now, being not dead, or even completely past. Of course, a comparison of historical and contemporary attitudes is something of an artificial construct in and of itself; while we might perceive past voices only through a glass, darkly, via diaries, documents, and art, these voices can enter into a dialogue with the present only through mediation by a third party, in this case, myself.[i]

In my mediation, I want to take several voices from the past and, hoping that I do not put too many words in their mouths, contrast their constructed realities with related constructs in the present. The culture-scape is baroque opera in the years 1724 and 2005. The lens is Georg Frideric Handel's opera Giulio Cesare in Egitto or "Julius Caesar in Egypt."[ii] I examine gender and sexuality interpretations that result from what has been called the "castrato problem." While this and many other baroque works were written specifically for castrati, the vocal superstars of the baroque era, the cessation of castration as a practice has thankfully forced contemporary opera directors to make a variety of choices when casting roles originally written for castrati. The resulting performances move beyond heteronormativity, and reinforce the characterization by culture scholars Corinne Blackmer and Patricia Smith of opera as a very queer art form (1995:8).

THE CASTRATI

To appreciate the nuances of contemporary stagings of baroque opera, we must begin with the history of the castrato. Castration is the surgical removal of the testicles. The practice of castrating boys for their singing voices—what has been called aesthetic castration, or castration for the sake of art—dates back to church choirs in early medieval Constantinople and 12th-century Spain, although there have been eunuchs throughout history.[iii] Boys were castrated before the onset of puberty in order to preserve their fine high singing voices, a goal unfortunately not always realized. When conducted before puberty, the surgery altered hormone levels in the male body and resulted in a comparatively plastic skeletal structure; a rounder, softer, and hairless face; and a body that was significantly larger than that of the average man.

Figure 1: Gaetano Berenstadt (left) and Senesino (right) flank Francesca Cuzzoni in a 1723 caricature by John Vanderbank of Handel’s Falvio (Kelly 2004:43).

During the Renaissance era, hearing a castrato sing was the privilege of the European elite, and these upper classes often included men of the church. In 1589, Pope Sixtus V issued a papal bull approving the recruitment of castrati for the choir of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, continuing the biblical edict from first Corinthians that women "shall keep silence in the churches." However, those recruited had to have lost their genitals through "tragic accident." As the castrati rose in popularity, the number of "tragic accidents" escalated, and it was estimated that some 4000 Italian boys were castrated per year by the early 18th century (Berry 2011:18).

While most castrati just barely eked out a living in church choirs, fame and fortune could be found on the operatic stage (Berry 2011:37). Some of the earliest operas—for example, Monteverdi's 1607 Orfeo—featured castrati, and the tradition continued well into the 1700s. Now in the present day, the practice of castration has thankfully ceased, and directors staging baroque operas must deal with the absence of castrati, or "castrato problem," when making casting decisions. Despite several interesting attempts to re-create it using computer technology—notably the BBC documentary Castrato and the film Farinelli, il Castrato—the baroque castrato's vocal timbre no longer exists. Contemporary directors, therefore, have a variety of options open to them that can only approximate the castrato sound. The vocal line might be transposed down an octave, of course, to be sung by a bass or baritone. But alternatively and more interestingly, the original vocal range might be maintained by assigning the role to a male falsettist or countertenor—that is, a man who sings primarily in his falsetto—or to a woman. Casting countertenors or women rarely results in performances that read as heteronormative to modern audiences. To examine these audience interpretations, I wish to contrast the meanings of historical and contemporary constructions of gender and sexuality as they relate to Georg Frederick Handel's opera Giulio Cesare in Egitto.

GIULIO CESARE

Handel premiered Guilio Cesare in 1724 as part of the sixth season at the Royal Academy of Music, also known as the King's Theatre, in the Haymarket of London. Like most baroque operas, it has many plots, subplots, and even sub-subplots! The main storyline follows Julius Caesar just after he has defeated and invaded Egypt. Much of the plot includes political (and romantic) maneuverings on the part of Cleopatra as she attempts to seduce Caesar into supporting her as the sole ruler against her brother, Ptolemy. Cleopatra's servant and confidant, Nirenus, provides comic relief.

In my analysis of gender and sexuality, I focus on these three male characters: the title character Julius Caesar; Cleopatra's brother, King Ptolemy of Egypt; and Cleopatra's servant Nirenus. The premiere cast featured castrati in all three roles: Senesino, Gaetano Berenstadt, and Giuseppe Bigonzi, respectively. The 2005 Glyndebourne Festival Opera version instead features two countertenors as Ptolemy and Nirenus and a woman en travesti or in drag playing Caesar.

GENDER AT THE PREMIERE

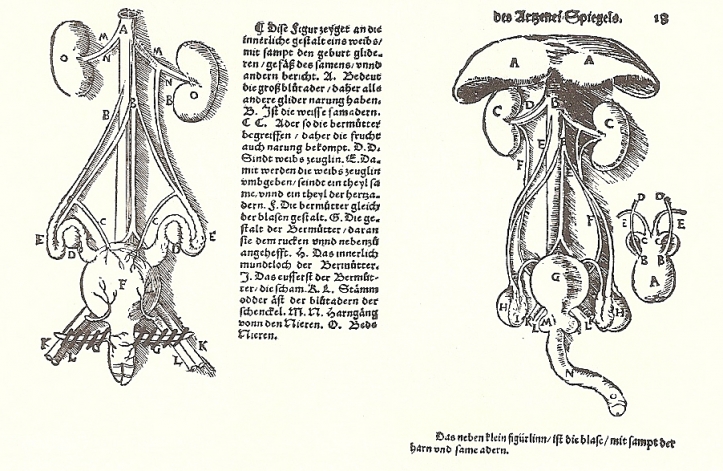

Although we do not know as much about the actual premier of Giulio Cesare as we would like, scholars such as Thomas Laqueur have been able to uncover a great deal about sexuality and gender constructs during this era. In the 17th and 18th centuries, words we use now to construct gender and/or sexuality identities like "gay," "lesbian," "queer," and "heterosexual" did not yet exist.[iv] Nor are they particularly appropriate. The Galenic model of biological sex still held sway, in which "men and women were arrayed according to their degree of metaphysical perfection," with men, of course, being more perfect than women (see figure 2) (Laqueur 1990:4-5). This model, also called the one-sex model, posited that men and women are essentially the same, the only difference being the genitalia physically expressed outside the male body (that is, the penis and testicles) are expressed analogously inside the female body (that is, the vagina and ovaries) (Laqueur 1990:4-5). Terms like "homosexual" and even "bisexual" did not have a place in this model, and men who practiced sodomy "were thus no different, no more effeminate, in their basic identities" than men we would now describe as heteronormative (Freitas 2009:114).

Figure 2: From 1542, the female reproductive system (at left) and the male reproductive system (right) illustrating the penis/vagina isomorphism (Laqueur 1990:86).

In this one-sex model, the castrato, much like the pubescent boy, functions as a kind of middle ground. Many seventeenth-century works of literature, art, and records of everyday life (nearly all of which were produced by men) repeatedly characterize the boy as an object of desire. Although significantly rarer, the castrato also fulfills a similar role. Scholars note that castrati were called "feminine men," "perfect nymphs," and "more beautiful than women themselves," descriptions that reinforce the castrato as a sexual and gendered middle ground. Perhaps more usefully, musicologist Dorothy Keyser characterizes the castrato in baroque society as an ambiguous figure, a blank canvas upon which any sexual role might be projected (1987/88:49-50).

The castrato as a blank canvas combined well with a period construction of "Italianness" in Great Britain.[v] This era witnessed a phenomenon called the "Grand Tour," an opportunity for British men of the upper classes "to escape the prying eyes and gossiping tongues of London polite society and indulge their passions, notably classical art and the 'sodomitical vice,' in the place that was thought of as synonymous with both: Italy" (Thomas 2006:173). Musicologist Roger Freitas has documented the castrato Atto Melani, who had several homosexual affairs with patrons; it is likely that other castrati also had sex with men (2009:101). Consequently, noblemen returning from the Grand Tour brought back an understanding and perhaps an appreciation of the increasing Italian tolerance for sodomy. The Grand Tour additionally functioned to connect the concept of sodomy with anything Italian, including the Catholic Church, priests, and of course, castrati.[vi] Therefore, the blank canvas of the castrati might easily include projections of sexual desire from audience members by virtue of their Italianness. This held true for women as well as men, especially because for women, the castrato was safe. No matter what sexual acts a woman might perform with a castrato, he was physically incapable of causing any scandalous pregnancies. Therefore, a woman's reputation would remain intact, even after an entertaining affair. Thus, in addition to aesthetic pleasure, the arias of Senesino or perhaps merely seeing Gaetano Berenstadt walk on stage had the potential to kindle sexual desire in any audience member.

Beyond the body of the castrato lies his voice. While I dislike disassociating the voice from the body, the fetish in the 17th and 18th centuries for the soprano vocal range cannot be ignored. This fetish began in 1580, when Duke Alfonso d'Este formed the concerto delle donne—a small ensemble of accomplished female singers—to entertain his new bride in Ferrara, Italy. The concerto delle donne soon became very famous, and attracted many new compositions. As their fame grew, their high tessitura became increasingly sought after, leading, some scholars propose, directly to the emergence of the castrati (McClary 2012:99).

Musicologist Susan McClary suggests that, upon hearing the concerto delle donne, many male spectators and artists might not only have "responded to the sound as an object of desire but actually coveted the subject position itself" (2012:100). Although these musicians and composers could hardly turn themselves into castrati, they could compose for them and promote them. Therefore, the soprano voice, whether it originated in a female or an altered male body, became an important fetish that could ignore gender demarcations. This leads directly to the often queer contemporary performances that result when casting roles written for castrati.

GLYNDEBOURNE GENDER

In solving the "castrato problem," the Glyndebourne chose to cast two countertenors, and a woman in drag in a production that mixes together British colonial, 1920s jazz-age, exoticized pseudo-Egyptian, and Bollywood aesthetics. Some contemporary audience interpretations of the resulting Glyndebourne production might include: Caesar and Cleopatra as a lesbian couple and the Egyptians as effeminate or homosexual men. These interpretations result from a combination of the bodies and voices of the actors, the costumes they wear, and the manner in which they portray their characters. This last component combines actual dance choreography with more general movement style, and the quality of movement—what we might call the choreographic timbre—is often more important than merely observing which parts of the body locomote. Of course, connecting movement with concepts or stereotypes of gender and sexuality is never easy, all the more so when one attempts to avoid oversimplification of remarkably complex cultural constructs.

From the point of view of at least one modern lesbian, there is an "interplay of erotically charged identification and difference" in casting a woman to play the character of a man (Blackmer and Smith 1995:5). This is especially true in cases where the male character must romance and/or rescue the heroine. Corrine Blackmer, Patricia Smith, and Hélène Cixous speak to the power of opera in general—"that seemingly forbidding and improbable realm of artifice—[where a woman could], through the power of her voice, transcend her gender and, more than love, rescue her own sex" (1995:5). In Giulio Cesare, one such moment happens vocally in the duet between Cleopatra and Caesar: "Caro! – Bella! Più amabile beltà" (2:15-2:37). Here, as Susan McClary might say, Sarah Connolly and Danielle de Niese's voices "intertwine, take turns being on top, rub up against each other in aching dissonances, [and] resolve sweetly together" (2012:101). Caesar might be a man, but Sarah Connolly is not, and there are distinct same-sex erotic moments in this duet as a result.

In addition to the charge created by two high voices originating from two female bodies entwined in a (seemingly) heterosexual love duet, there is the question of the choreography. Connolly performs a very masculine Caesar, who swaggers around the stage with a decisive step, or who sits with feet planted firmly apart, a body full of straight lines with few curves. The stereotypically masculine movement quality that Connolly brings to the role is thrown into high relief when contrasted with Ptolemy's immature or somehow "gay" movement quality in the recitative preceding Caesar's aria "Va tacito e nascosto" (0:12-0:30 and 1:05-1:35).

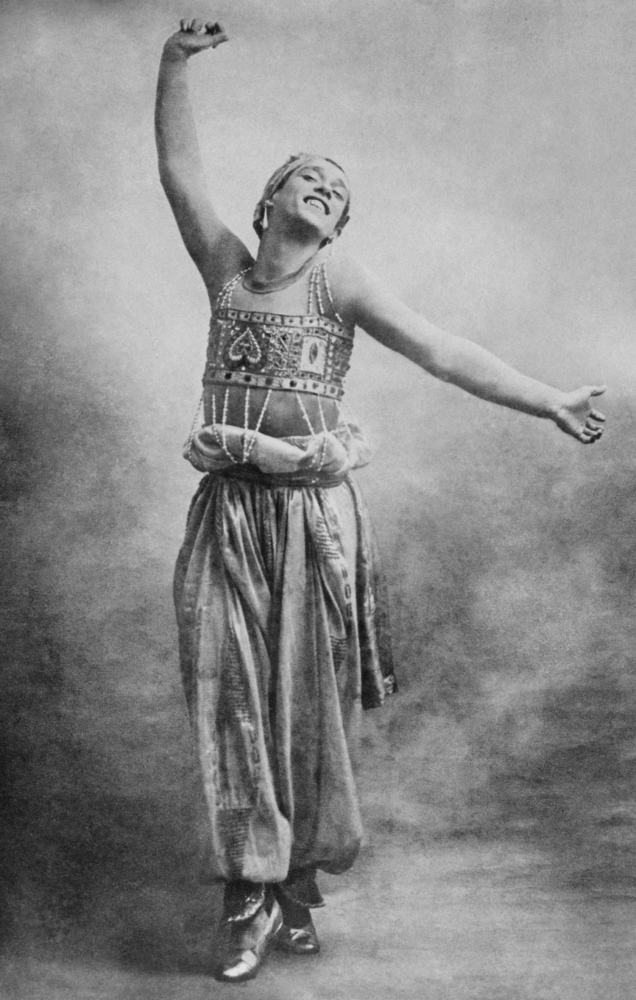

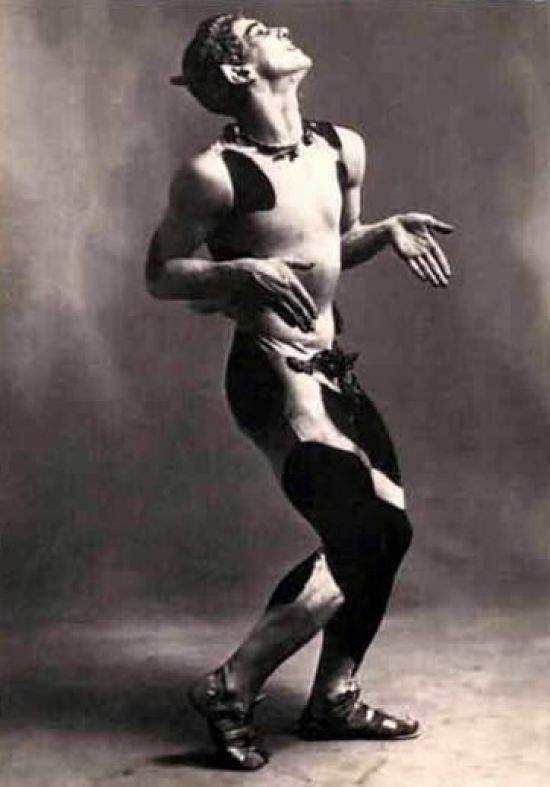

In contrast to the strong Caesar, countertenors Christophe Dumaux and Rachid Ben Abdeslam perform their Egyptian characters as homosexual, even effeminate. Both actors are thin, lithe men, and throughout the production both combine feminine costumes and/or movement qualities to great effect. For example, there is the gender bending outfit Ptolemy wears during his aria "Belle dee di questio core." The costume is evocative of that of belly dancers, and comprises a turban, earrings, stylized wrist cuffs, a top that combines a belly dancers breast band with the harness worn in a leather bar, a sirwal or punjabi pants, and a robe, which Ptolemy removes to great hilarity from the audience (see figure 3). His costume is reminiscent of that worn in 1910 by Vaslav Nijinsky, the queer choreographer for Les Ballets Russes, in their production of Scheherazade (see figure 4). In his aria, Ptolemy alternates stereotypically gay, feminine, or effeminate movements with hypermasculine gestures. For example, the luxuriant manner in which he removes and swirls his robe and slinks around the stage as compared with the pose in front of the mirror and the somersault, which have an almost violent flavor to them. In addition, there exists a choreographic quotation which, while evocative of stylized ancient Egyptian art, also comes from Nijinksy: toward the end of the video clip, Christophe Dumaux references Nijinsky's Faun in L'après-midi d'un faune from 1912 (see figure 5). The inclusion of these reference to Nijinsky, who holds an important place in LGBTQ histories, further queers this aria (0:00-1:00).

Figure 3: Christophe Dumaux reprising his 2005 role in the 2013 Metropolitan Opera production of Giulio Cesare (Photo courtesy Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera).

Figure 4: Vaslav Nijinsky in Scheherazade, 1910 (photo courtesy Library of Congress). [http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ggbain.19576/]

Figure 5: Vaslav Nijinsky as the Faun in the 1912 production of L'après-midi d'un faune (from http://thebestofhabibi.com/vol-18-no-3-march-2001/ballet-as-ethnic-dance/).

There is also the aria "Chi perde un momento" sung by Nirenus. In this dance sequence, Nirenus and his—interestingly male and not female—backup dancers perform a number drawing on conventional Bollywood choreography with campy and effeminate gestures. Their hands form sinuous curves, at times as though as they are manipulating skirts, and they clearly have fun with the stereotype of the gay man with limp wrists. Additionally, their extensive hip movements are more typically associated with women, as is the hand on the hip. All three performers also exchange occasional flirtatious glances (0:17-0:45).[vii]

The characters of both Nirenus and Ptolemy are realized by countertenors. Countertenors are defined as men who develop their falsetto range, sometimes called the head voice. Although both male and female voices are capable of realizing a plethora of high and low pitches, gender norms are challenged when a woman sings very low and particularly strange when a man sings very high. Contemporary Euro-American cultures by and large construct masculinity as characterized by a lower vocal register. Deviation from this expectation is cause for surprise. Therefore, while both Christophe Dumaux and Rachid Ben Abdeslam augment their performances with stereotypically feminine and campy choreographies and costumes, the heart of the perceived effeminacy of their characters lies in their tessitura. The conflation of high male vocal tessitura with alternative or deviant sexuality and/or gender identity has existed since the renaissance of the countertenor voice in the 1940s with the British countertenor Alfred Deller. From all appearances a Kinsey zero and devoted family man, Deller was plagued throughout his career by perceptions that he was a eunuch or otherwise abnormal. The stereotype continues to the point that even now heterosexual countertenors often feel they have to come out of the closet as "straight." Consequently, the first note sung by a countertenor on the operatic stage immediately reads as some kind of queer to contemporary audiences, for surely any "normal" man would choose to sing in his chest voice. Creating the character with stereotypically gay choreographic timbres merely augments what the voice began.

CONCLUSION

The castrato's physical absence from the stage results in performances that open spaces to comment on contemporary gender and sexuality norms and identities. Caesar, that strong and masculine Roman general, becomes a strong and butch lesbian. Ptolemy, the inefficient Egyptian king and politician, becomes a villainous fairy. The servant Nirenus becomes a sissy or pansy. Stereotypical masculinity and femininity are questioned, altered, and otherwise queered through the very act of answering the castrato problem. However, no matter what option a contemporary director chooses—whether to transpose the music down for a bass, or cast a woman in drag, or countertenor—the sound and/or the sex of the contemporary performer still differs from that of the castrati. In comparison, the bass sings too low, the woman in drag is too female, and the countertenor's voice sounds too thin and reedy. The difference, perceived through the vocal timbre or body of the contemporary actor, creates comparisons with what might have been. The castrati are still fetishized, as evidenced by the recent surge of interest in Baroque repertoire in general and in the number of countertenors recording albums explicitly dealing with the castrati.[viii] In the very attempt to replace them or sing anew their music, their absence re-creates their presence. As contemporary performances signify and re-signify the original powerhouse acts of the castrati, those baroque-age celebrities are still present, and their voices might still be heard through the very fact of their absence: they are not dead, they are not even past.

References:

RECORDINGS

Bach, Johann Christian. 2009. La dolce fiamma: Forgotten Castrato Arias. Philippe Jaroussky, countertenor. CD (Virgin Classics 5099969456404).

Castrato. 2006. Francesca Kemp, director. BBC Channel Four.

Fagioli, Franco, countertenor. 2013. Arias for Caffarelli. CD (Naïve V 5333).

Farinelli, il Castrato. 2000. DVD. Gelrard Corbiau, director. Stephan Films. (Columbia TriStar Home Video 10629).

Handel, Georg Frideric. 2005. Giulio Cesare. DVD. Glyndebourne Festival Opera, William Christie, conductor, David McVicar, director (OA 0950 D).

Hansen, David, countertenor. 2013. Rivals: Arias for Farinelli. CD (Sony Music 88883744012).

Jaroussky, Philippe. 2007. Caristini: The Story of a Castrato. CD (Viorgin Classics 0094624228).

PRINT MATERIALS

Berry, Helen. 2011. The Castrato and His Wife. New York: Oxford University Press.

Blackmer, Corrine E. and Patricia Juliana Smith. 1995. "Introduction." In En Travesti: Women, Gender Subversion, Opera, edited by Corrine E. Blackmer and Patricia Juliana Smith, 1-19. New York: Columbia University Press.

Dame, Joke. 2006. "Unveiled Voices: Sexual Difference and the Castrato." In Queering the Pitch: The New Gay and Lesbian Musicology, edited by Ed. Philip Brett, Elizabeth Wood, and Gary C. Thomas, 139-154. New York: Routledge.

Faulkner, William. 1950. Requiem for a Nun. New York: Vintage Books.

Freitas, Roger. 2009. Portrait of the Castrato: Politics, Patronage, and Music in the Life of Atto Melani. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harris, Ellen T. 2001. Handle As Orpheus: Voice and Desire in the Chamber Cantatas. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Kelly, Thomas Forrest. 2004. First Nights at the Opera. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Keyser, Dorothy. 1987/88. "Cross-Sexual Casting in Baroque Opera: Musical and Theatrical Conventions." Opera Quarterly 5(4): 46-57.

Laqueur, Thomas. 1990. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

McClary, Susan. 2012. Desire and Pleasure in Seventeenth-Century Music. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rousseau, George S. 1991. Perilous Enlightenment: Pre-and Postmodern Discourses: Sexual, Historical. Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press.

Stone, Lawrence. 1977. The Family, Sex and Marriage in England, 1500-1800. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.

Thomas, Gary C. 2006. "'Was George Frideric Handel Gay?' On Closet Questions and Cultural Politics." In Queering the Pitch: The New Gay and Lesbian Musicology, edited by Ed. Philip Brett, Elizabeth Wood, and Gary C. Thomas, 155-204. New York: Routledge.

Tougher, Shaun, ed. 2002. Eunuchs in Antiquity and Beyond. London: Gerald Duckworth and the Classical Press of Wales.

[i] I am very grateful to Rose Boomsma, Tara Browner, Scott Linford, Naveen Minai, James Newton, A.J. Racy, Roger Savage, Timothy Taylor, and attendees of the 2013 Society for Ethnomusicology conference in Indianapolis for their critical feedback on early drafts of this paper.

[ii] There have been several attempts to untangle the sexuality of Handel himself—indeed, a cantata text written for him by Cardinal Pamphili in 1707 directly compares Handel to the mythological Orpheus who, even then, "provided a double emblem of musician and homosexual" (Harris 2001:2). Although it is beyond the scope of this paper, Handel's sexuality adds yet another layer of signification to this narrative (Thomas 2006).

[iii] See for example, essays in Tougher (2002).

[iv] Indeed, "homosexual" did not appear in print until 1869 in Germany in a pamphlet by the novelist Karl-Maria Kertbeny.

[v] For more on the complex sexuality of the castrato, see Dame (2006).

[vi] See, for example, Rousseau 1991; Stone 1977; and Thomas 2006.

[vii] I am very grateful to Jaedra DiGiammarino, Kaitlyn Jurewicz, Layla Meyer, and Turya Nair for their input in describing and analyzing these different choreographies.

[viii] For example, see Bach (2009), Fagioli (2013), Hansen (2013), and Jaroussky (2007).