Trap: A Reappraisal of Stigmatized Practices and Music Experimentation

Introduction

Trap is a music genre (or sub-genre) in high circulation since 2012, when its presence in social networks and the rise of scenes or communities around the world became evident.[1] Its origins can be traced to the suburbs of Atlanta, in the United States.

The few press articles commenting on the phenomenon—usually based on the notoriety reached by some bands, and always linked to shocking discourse or events involving the artists—describe it as “nihilistic, sexual and narcotic rap” or, referring to the generational profile of its followers, “the music parents hate.” The only academic work that takes trap as its object of study is Alexandra Baena Granados’ doctoral dissertation (2016) on the trap scene in Barcelona.

Trap is a slow-tempo music, with a stable pulse. Its base is programmed from the sounds of an 808 (a 1980s beatbox deemed obsolete due to its artificial sound quality, in contrast to subsequent models) and completed with a strong bass line, effects, sampled fragments and different layers conceived as modules; combined, overlapped or silenced throughout each song.[2] The voices of singers are added, often heavily manipulated by the producer, who stands out as the real driver of the whole process, using filters and adjustments.

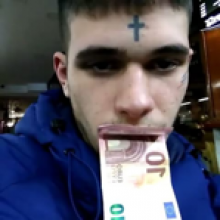

Figure 1: Anuel AA, an exponent of trap in Spanish. Money as a desire and way of life.

A trademark of the trap genre is how it is consumed, produced, and broadcast. Similar to rap, but differing from it musically and conceptually, trap sustains itself outside of the commercial market as bands choose to operate underground, using social networking websites and online platforms for music and video circulation. Most of those who make and listen to trap find in the internet not only their main source of information and music storage, but also a way to obtain music production software, promote their own music, and carry out collaborations, without the need for travel. The producers and/or singers are in charge of circulating their songs via Facebook, YouTube or Soundcloud, where they can also get in touch with each other and receive support or critique. A “do it yourself” ethos and a conflicting relationship with the recording industry are clear features of the genre.

Our research focuses on trap in Spanish, including artists from the northern hemisphere (such as Los Santos [formerly Pxxr Gvng], Cecilio G., Pimp Flaco, Fuete Billete and Anuel AA), and from South America (such as Malandro Malajunta, Trap Drillers, Lastre, Zeta Drew, Lil Jer, Nueve9tres, Pvblo Chill-E, MC Guime, and Cachorro Gordo).

In this post, we describe the scene and offer some preliminary observations about the relationship between trap music, social processes, and contemporary youth identities. We will begin by exploring vocal style in trap; we will then note the lyrical content of trap songs, commenting on the use of sampling and quoting; and finally, we will discuss the marginalized position of trap artists.

“Los pobres” by Pxxr Gvng

Voices: How Lyrics Sound

According to interviewees, trap music has its roots in the use of certain drugs, their effects and the environment they condition. As one interviewee, a member of the band Nueve9tres told us:

It also has to do with using drugs. What makes trap different is that you make it inside your room. Trap’s what happened to hip hop artists once they tried certain drugs and got into their home with a computer to make music. Codeine’s used, a lot. Everything becomes slower and voices are distorted. When the effect wore off and they wanted to keep listening in the same way; when trying to achieve that, trap came about.[3]

Lyrics and videos brim with references to rejected practices, such as drug consumption and dealing, misogyny and sexism, and the display of wealth and theft, among others.[4] At the same time, trap is enriched by challenges between artists—threats and the exchange of messages through songs. These themes are not entirely new or, at least, they are present in other genres, such as Mexican narcocorridos, cumbia villeraor gangsta rap. But, unlike the aforementioned examples, trap seems to be exclusively devoted to them; they seem to constitute its backbone.

Figure 2: Singer Khaled, displaying brands and jewelry.

Trap vocals are heavily artificially modified. The most commonly used filter is Auto-Tune. Its original function was to correct a singer’s tuning while recording or performing live, but heavy use changes the tone or “color” of the voice. Such is Baena Granados’ claim in her study of trap in Barcelona: “Auto-Tune has gone from being an effect used on someone’s voice to a music style, a sound in itself and the watermark of a musical genre” (2016:60).

The filter gives amateurs the opportunity to make music and sing. Facundo (Joven Mannson), of trap group Nueve9tres, told us:

I’d never sung before; I didn’t have any musical phrasing at all. We said “dude, let’s do it”, half joking, half seriously and really got going. The other guy and I are party buddies; we started listening to music together, and he turned me on to trap. We said, “if there’s people doing that and they’re young guys just like us, we can do it...” and it worked.JXY3RX [artistic name of Cristian Gualpa]handles production; that’s why it sounds like that, or else, it would suck.[5]

Distorted voices and different intonations embody narratives of outlaw or the “street” experiences.

“Drink & smoke” by Trap Driller$

Lyrics: What Is Said

The ostentatious show of wealth (dollar bills, jewelry or high-end cars) is one of the strongest trademarks of trap. Both the desire to be rich and the satisfaction of having money are conveyed in numerous trap songs. In both situations, the fundamental counterpoint is embodied by poverty. The fact that one comes “from the slums” and achieves economic success surfaces as the very basis of trap’s narrative. Pvblo Chill-E’s “Empezamos de cero,” for example:

Having money’s what I want / Travel abroad / Want bills of twenty / Want gold on my teeth / Want a house on the beach / Want my sound in all continents / Wanna drive my Ferrari up front / Speakers blasting my songs

“Empezamos de cero” by Pvblo Chill-E

The attainment (real or desired) of that wealth is often shown as a result of survival strategies such as drug dealing or petty crime, as seen in Zeta Drew’s “Trabajo en el descanso:”

I came from the slums and now just chill / I found a shortcut to count my stacks / What others say / I don’t give a shit / I chill at work and work at chilling

This last reference by Zeta Drew—accompanied in the video by a fictitious scene of drug dealing in a slum—serves as a link to another favored topic in trap: belonging in a neighborhood and being in the know of its codes.[6]

Another dichotomous pair posed by trap is being “real” or “fake.” The matter of first-hand experience in the situations sung about or shown in videos becomes central to legitimacy or rejection within the scene.

The point of view established regarding life in the neighborhood and the possibilities it offers differs from other genres, which have approached the same topic from a different perspective. For example, hip-hop and conscious reggae lyrics include critical references to the police, injustice and the destruction of the planet, but also include proposals for unity and awareness-raising concerning these issues (Caldeira 2010, Bravo 2016). Trap moves away from these stands; it seems to mistrust these messiahs and spokespeople nobody appointed. Trap artist Joven Mannson makes this very important point:

There is a generational issue which makes conscious rap old, aging. Do not tell me what’s right or wrong, because it’s bullshit. Some hip-hop guys insult us because they say, “This is not ‘hood’” ... That social message with no fundaments, because it is ok to sing about it, but if you do not put it into practice, you’re an asshole.

Songs often mention well-known figures: drug lords like Pablo Escobar or Chapo Guzmán are highlighted as paradigmatic figures in a lifestyle outlined as an aim. Diego Maradona is also mentioned in some songs, both as being associated with cocaine and because of his straightforward attitude, which reinforces the notion of being “real.”

Although the coherence between what is said and what is done cannot be ascertained, it is worth mentioning the internal coherence of this particular discourse, reinforced by images. Likewise, the topics mentioned coexist with other kinds of references, such as love for one’s mother or friends, loyalty, and video games or anime characters. It is also possible to identify instances or cases of references to less controversial issues, such as loneliness and lack of love or future prospects.

Sampling and Quoting in Trap

Unlike rap or electronic tango, which feature samples of recognizable sources (Greco and López Cano 2015), seeking to vindicate an artist, movement, or state a point of view, samples in trap are not usually identifiable.[7] Music journalist Diedrich Diederichsen distinguishes three temporal levels in hip hop: the “individual and linear history of sung rap, the circular time of groove and, finally, the single’s fixed reference point, i.e. the quote conceived as history” (2005:119). The first level makes reference to hip hop’s narrative time, mostly in the early 80s, where a poem or manifesto’s organization style is evident, with a beginning, a middle part and an ending. This time opposes the time of the groove, which is circular instead of linear. On the third level, musicians incorporate selected excerpts of speeches by leaders of civil rights or integration movements for black people. According to Diederichsen, samples and their origins were not hidden, but treated as a historical source and epochal sign to be reappraised.

On the contrary, everything seems to be about the here and now in trap. How should we analyze this? One possibility is to conceive samples in trap music as "quotes," as Brazilian sociologist Renato Ortiz poses, within the notion of “international-popular memory:”

Asserting the existence of an international-popular memory is to acknowledge the fact that, within consumer societies, globalized cultural references are built. The characters, images, situations, carried by advertising, comics, television, cinema, become the substrates for this memory. Everyone’s memories are inscribed in it. (Ortiz 1997:173)

By not appealing to referential figures for support, trap artists seem to respond to the generation’s own perception of their music as something new. Both in interviews and lyrics, "old" means 1990s "conscious" rap. Discursive and musical references to "retro" refer to that decade. There does not seem to be an interest in expressing a genealogical line but rather in opening intra-generation dialogues.

Those who study late modernity often discuss how time is experienced. Rosa Hartmut (2016:25) describes temporal acceleration as a "contraction of present." While the past is "that which is no longer sustainable/valid," the present is the period of time coinciding with "experience spaces and expectation horizons" (ibid: 26). As part of the many consequences entailed by these changes, Hartmut points out the evident moving from "an intergenerational rhythm in early society to a generational rhythm in classic modernity and an intragenerational rhythm in late modernity" (ibid:27). We suggest that sampling in trap reinforces a temporality set in the present that serves, above all, as a tool for communication among peers.

Tentative conclusions

We have argued here that trap is a recent musical phenomenon with some connections to other musical genres and styles, but that it differs from them both in the images it conveys (lyrical or visual) and in the fact that it exists mainly on social networking websites, as opposed to the commercial recording industry. Trap performers are usually part of marginalized youth groups, marked by poverty, discrimination or problematic drug use. They are unified in the representation of these realities, based on the exacerbation of stigmatizing or politically incorrect elements according to today’s common sense and the canons imposed by the media.

One of the most important features of trap is the stigmatized identity profile its performers embrace. Instead of refuting or rejecting these labels (being poor, marginal or linked to crime), trap artists embrace them.

The lack of recognition from the mainstream music industry and commercial circuits represents another way in which trap artists are marginalized, but this has largely been solved by self-management and the use of social networks and internet music platforms as a guarantee for existence. In others words, paradoxically, the exclusion from commercial and recording circuits seems to also allow for trap’s sustainability and development in its own terms.

Although there are continuities within the music produced and consumed by young people in low-income sectors around the world, at discursive, aesthetic and ultimately, conceptual levels, there is also evidence of some ruptures that require further research.

Trap is a phenomenon that can be heard as echoing punk’s do-it-yourself attitude, from the bid for self-management to the way it pushes boundaries, creating something new not only at the level of discourse but also in its sound. At the same time, stances on money, crime and women suggest a certain conservatism. Trap is, ultimately, (self-)defined as a music scene that serves to express the current marginality of its practitioners.

References

Adaso, Henry. 2016. “The History of Trap Music. Remember crunk?”. Thought Co, May 12th, http://rap.about.com/od/genresstyles/fl/Trap-Music.htm. [Accessed 28 September 2017].

Baena Granados, Alexandra N. 2016. “I’m in the fucking Krakhaus, fuck you bitch!” La escena trap de Barcelona. Dissertation thesis, Universitat de Barcelona.

Bravo, Nazareno. 2016. “Rieles de acero en tiempos de caos: El reggae rasta en la Argentina neoliberal y la construcción de identidades juveniles”. InPensamiento Alternativo en la Argentina Contemporánea; Derechos humanos, resistencia y emancipación (1960-2010), Tomo III, compiled by H. Biaggini and G. Oviedo,457-475. (Buenos Aires: Biblos).

Caldeira, Teresa. 2010. Espacio, segregación y arte urbano en el Brasil.(Buenos Aires: Katz).

Diederichsen, Diedrich. 2005. Personas en loop: ensayos sobre cultura pop. (Buenos Aires: Interzona).

Greco, M. Emilia and López Cano, Rubén. 2015. “Evita, el Che, Gardel y el gol de Victorino: Funciones y significados del sampleo en el tango electrónico”. Latin American Music Review36: 1, 228-259.

Hartmut, Rosa. 2016 [2003]. Alienación y aceleración. Hacia una teoría crítica de la temporalidad en la modernidad tardía. (Buenos Aires: Katz).

Ortiz, Renato. 1997. Mundialización y cultura. (Buenos Aires: Alianza).

Notes

Article translated from Spanish by Gustavo Kletzl.

[2] Beatboxes are, in short, electronic musical instruments that allow for the composition of rhythm patterns emulating a drum kit. The 808 is a particular model: the Roland TR-808. Briefly, it is a beatbox that enabled programming and combining previously designed rhythm patterns, but did not use sounds from a real drum kit. It was launched a few weeks after the first beatbox using drum samples (i.e. sounds or samples taken straight from a drum kit), which was considered a better version. Thus, the price of 808 was drastically reduced a few weeks after its launch and it became affordable for a wider audience.

[3] Cristian Gualpa (artistic name: JXY3RX) interview, member of Nueve9tres, July 28th, 2016.

[4] The issue of misogyny and sexism in trap deserves more scholarly attention. At first, trap music might appear deeply chauvinistic. Similar themes can be found in cumbia villera (slums cumbia) and hip-hop. However, it is worth mentioning that there are female trap performers who engage in this chauvinistic discourse, which makes matters more complex.

[5] Facundo (artistic name: Joven Mannson) interview, member of Nueve9tres, November 24th, 2016.

[6] It should be noted that the video was eliminated from YouTube, we believe for showing drug dealing and use.

[7] There are some exceptions: dialogue fragments from a B movie, “Killer Klowns from Outer Space” (1988); fragments of Diego Maradona’s declarations on a song by Pvblo Chill-E; and the voice of flamenco singers in Spanish productions.

Biography

Nazareno Bravo (INCIHUSA/CONICET – FCPyS/UNCuyo) is a sociologist with a PhD in Social Sciences. CONICET (National Scientific and Technical Research Council) Researcher since 2012. Professor of Sociological Bases at the School of Political and Social Sciences (FCPyS), Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. His areas of interest include social, political and cultural processes involving youth; arts, memory and participation.

María Emilia Greco (FAyD/UNCuyo – INCIHUSA/CONICET) is a music teacher, specialized in Music Theories at the School of Fine Arts and Design (FAyD), Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, with a PhD in Social Sciences, School of Social Science, Universidad de Buenos Aires. She is a Professor of Music Analysis at the School of Fine Arts and Design (FAyD), Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, and a CONICET (National Scientific and Technical Research Council) grant holder since 2009. Her areas of interest include popular musical practices and their role in the construction social identities, in current times and their historical constitution.