We Got the Jazz: Next Generation Jazz, Hip Hop and the Digital Scene

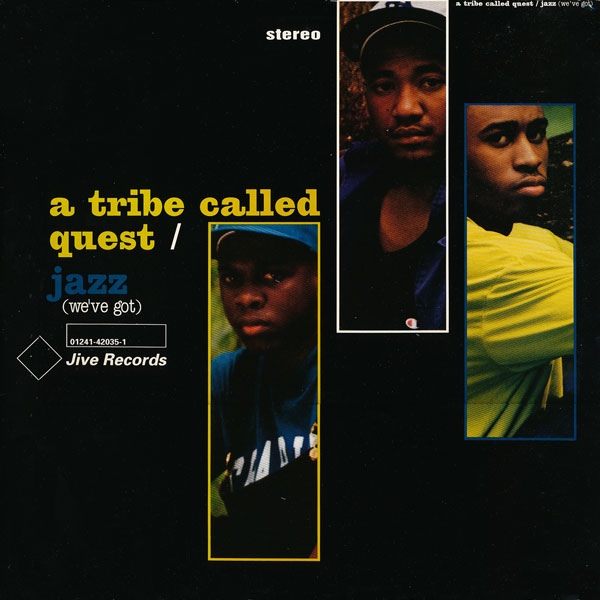

In 1991, American hip hop group A Tribe Called Quest released "Jazz (We've Got)" on their second album The Low End Theory, which featured a sample of Jimmy McGriff and Lucky Thompson’s live version of "Green Dolphin Street" from their album Friday the 13th Cook County Jail. In addition to the prominent sample, the lyrics, proudly proclaiming “we got the jazz, we got the jazz,” point to an already present and burgeoning interrelatedness between hip hop and jazz, despite the latter’s waning popularity among young African Americans.

Now, over 20 years later, the first generation of jazz artists who came of age in an era when hip hop had a strong presence in American popular culture are emerging as leaders of a new school. In tandem, a new jazz audience is also emerging that is highly responsive to and enthusiastic for the progressive exploration of harmony, rhythm and melody infused with styles from hip hop, rock and pop music of their time. Further, the use of digital technology to disrupt leading practices in the traditional recording industry has led to burgeoning online communities and innovative live presentations of jazz that embrace tradition while boldly forging new paths for future possibilities.

As a person who came of age in a time when hip hop was emerging as a popular genre across the nation, first in urban, predominately black American communities and then globally, I (like many in my peer group) developed a strong relationship to the music that seemed to express our present experiences and reality. On the other hand, jazz was something that was shared with me by parents and grandparents or sometimes through special guests, theme songs and music cues on The Cosby Show. It was something to enjoy, respect, revere, learn about and even celebrate as a part of my cultural heritage, but not exactly something that I felt was “of my time,” despite the fact that I was aware that new jazz was happening all the time.

Through my recent work with jazz musicians and audiences in New York, I began to consider continuity and change as they relate to the “scene” by considering both physical and digital space. As I found myself supporting a vast range of incredible work in a living genre that many may speak of in terms of the archaic, I found that tradition and modernity operated in tandem in fresh and innovative ways. This piece shares my initial thoughts that explore the impact of shifts in aesthetics, tradition, transmission, sound, industry and new forms of technology on audience and approach in the digital era. After discussing some early examples of the connection between jazz and hip hop, I look at a few recent projects that build on this legacy: the Revive Music Group, pianist Kris Bowers' cover of Kendrick Lamar’s “Rigamortis,” and Lamar’s own album To Pimp a Butterfly.

In early hip hop, samples and other musical references were more commonly associated with funk and soul—such as the frequently sampled catalog of James Brown—than with jazz. However, an interesting trend took place in the mid to late 80s and into the 90s that has been coined as “Jazz Rap.” Examples of this trend include Cargo’s Jazz Rap, Volume One (1985), Gang Starr’s single “Words I Manifest” (1989), Stetsasonic’s “Talkin’ All That Jazz” (1988), ATCQ’s “Jazz (We’ve Got)” (1991), Digable Planets’ Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time and Space) (1993), Nas’s Illmatic (1994), as well as the work of The Roots, Guru, Common Sense, Madlib, Fat Jon and Dilla.

For both jazz and hip hop, the record is an important object. In jazz, it is invaluable as both art and artifact, both offering sonic information as well as marking an important time, development, memory and/or moment. In hip hop, it is also valued in those ways, and given that the turntable plays an integral role in musical production, it is important not only as a playback technology but also as an instrument. Vinyl, in particular, is as much art and artifact as it can be a means by which to demonstrate musical knowledge and musicianship. Plainly speaking, for both lovers of jazz and/or hip hop, the record can be vital and quintessential.

We see a meeting of these perspectives on the importance of the record with the single version of “Jazz (We’ve Got).” On the album cover, the Jive Records logo and members of A Tribe Called Quest are pictured within cover art that references classic Blue Note albums from earlier eras rather than reflects trends in cover art or design of its time.

In the world of a genre that fully engages with recorded sound, jazz recordings in particular can serve as endless sources of musical ideas, phrasing, and sonic material. But they also do something else. The use of and references to jazz recordings in hip hop firmly link past and present, sonically and often visually connecting the two as integral to the African American musical continuum.

Beyond the use of recordings as in “Jazz (We’ve Got),” personal relationships and musical training also played a role for some hip hop artists in the turn to jazz as a source of sonic material, technique development, and conceptual approach. Biggie Smalls learned diction and phrasing from jazz saxophonist Donald Harrison, Rakim played the saxophone and notes John Coltrane as an influence, Ishmael Butler of the Digable Planets has described his access to his father’s jazz records, and Nas is the son of jazz musician Olu Dara. All these examples are not happenstance or coincidental; the relationships to jazz for these hip hop artists and others are evidence of a much more general trend in urban, African American communities. Experiences of jazz and its recordings are often rooted in familial and community relationships and may transcend those of, say, simply stumbling upon an old jazz record. In other words, a record is not just any record, it’s “your dad’s record,” and can come to be associated with everything it means to him, to you, and to your relationship.

At the same time that hip hop artists were looking to jazz, jazz artists were also paying attention to and engaging with hip hop. Important examples include Herbie Hancock’s Dis Is da Drum (1994), the collaboration between Branford Marsalis and Gang Starr’s DJ Premier in Buckshot LeFonque, Ronny Jordon’s The Antidote (1992) and his Blue Note debut A Brighter Day (1999), which features DJ Spinna and rapper Mos Def.

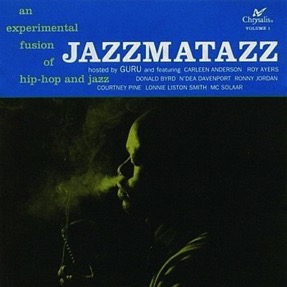

The Jazzmatazz series, produced by Gang Starr’s MC Guru for Chrysalis Records between 1993 and 2007, was an important studio album project connecting the two genres. One of major contributions of this album series was that it presented rap over live jazz, a development that had not yet fully been explored hip hop. In a way, the series stands as a quintessential representation of the overtly hybridized “Jazz Rap” movement and a pivotal moment with respect to what happens next for the interrelatedness between jazz and hip hop.

Like ATCQ’s single, Guru’s Jazzmatazz, Vol. 1 (1993) cover art references the cool aesthetic of classic Blue Note albums. Specifically, the artwork stands as a likely homage to Art Blakey’s A Night at Birdland, Vol. 1 (1954), featuring the live sets of a pre-Messengers line-up, released as a series, and influential as a breakthrough in modern jazz. Just a quick look at some of personnel from Jazzmatazz, Vol. 1 gives a sense of the musical range, depth and intersection represented on the recording as both forward-looking and grounded in a distinct knowledge of tradition; performers include Roy Ayers, Carleen Anderson, Donald Byrd, Lonnie Liston Smith, N’Dea Davenport, Branford Marsalis, and Ronny Jordan.

While “Jazz Rap” and the practice of utilizing jazz samples fell out of popularity and came to be viewed as outdated, the relationship between jazz and hip hop never truly stopped. Pressing the fast forward button about twenty years or so, we are now living in a time period when hip hop would have been an ever-present part of a younger jazz artist’s soundscape. And like their predecessors, young musicians continue to root their music in the tradition while exploring and adapting the popular music of their time and embarking upon paths of their own.

Around 2006, Revive Music Group (RMG), first branded as Revivalist and Revive da live, was founded by Megan Stabile, who has since risen to much well-earned acclaim as a successful and groundbreaking entrepreneur. Revive Music is an online hub presenting both rising and established jazz artists to new and younger audiences. RMG is currently the jazz extension of Okayplayer, a leading online community for hip hop artists and audiences since its inception in 1999. The almost familial relationship between RMG and Okayplayer is a digital manifestation of the continuing interrelatedness between jazz and hip hop. It demonstrates a keen awareness of musical kinship and a sense of community amongst artists, producers, supporters, and audiences.

Revive’s impact is illustrated by its mission statement, which asserts, “By illuminating the renewal of retro and classic music with that of new emerging genres, we are the center of a cultural resurgence of live music” ("About"). While there is much innovative and exciting content available online, the question of what is happening offline remains. What’s become of New York’s jazz scene of yesteryear? In a time when a great many jazz venues in New York City have closed or changed formats entirely, RMG has become a leading presenter of distinctive live performances that re-imagine jazz in a contemporary sense and create entirely new music in New York and globally. Every week in Greenwich Village, RMG hosts the Evolution Jam Session at the Zinc Bar, and the group regularly presents its homegrown Revive Big Band, led by trumpeter Igmar Thomas.

The band also features rapper, turntablist, and Berklee College of Music professor Raydar Ellis. Of Ellis, jazz writer Willard Jenkins has said:

The soul of the RBB’s hip hop perspective is rapper-turntablist Raydar Ellis, who is completely immersed in the form, has the in-the-pocket cadence and couplets down, has the requisite moves & stage presence, but sans the hard guy/male diva/I’m-a-gazillionaire-and-you’re-not posturing persona of so many rappers. (quoted in Reyes 2014)

Of Revive’s commitment to the relationship between jazz and hip hop, Ellis himself notes: “Revive is just trying to show the world it's not so much a divide it's just a family reunion and that’s what makes it both individual and shared” (personal communication).

The existing relationship between hip hop and jazz, the importance of records and recording, and the rise of a digital space to build communities as well as market and promote performances created a perfect and well-received storm for jazz to be interpreted and presented by a younger generation to new audiences. Other examples of such genre-defying jazz artists are Robert Glasper, Kris Bowers, Thundercat, Brandee Younger, Ambrose Akinmusire, Christian Scott, Mark de Clive-Lowe, and Marcus Strickland.

Another recent instance of the relationship between jazz and hip hop was keyboardist Kris Bowers’ cover of “Rigamortis” by rapper Kendrick Lamar, whom Bowers has counted as a personal favorite. Bowers makes musical choices and utilizes techniques that demonstrate a close listening to and command of jazz, hip hop and even 20th century prepared piano techniques. The video of the performance can also be read as an homage to his mentor and former teacher pianist Eric Reed, given that Lamar’s version makes use of Reed’s composition “The Thorn” from Willie Jones III’s album The Next Phase (2010).

However, like any kinship, everything isn’t a sunny day in the park. There is a pending litigation of Lamar’s use of “The Thorn,” which was not cleared for the track that was originally released on a mixtape and later achieved great commercial success.[1] This case stands as an illustration of both the ever-increasing compatibility between the genres stylistically and the ongoing conflicts over intellectual property rights. With any luck, this case is well on its way to a resolution with artists justly compensated.

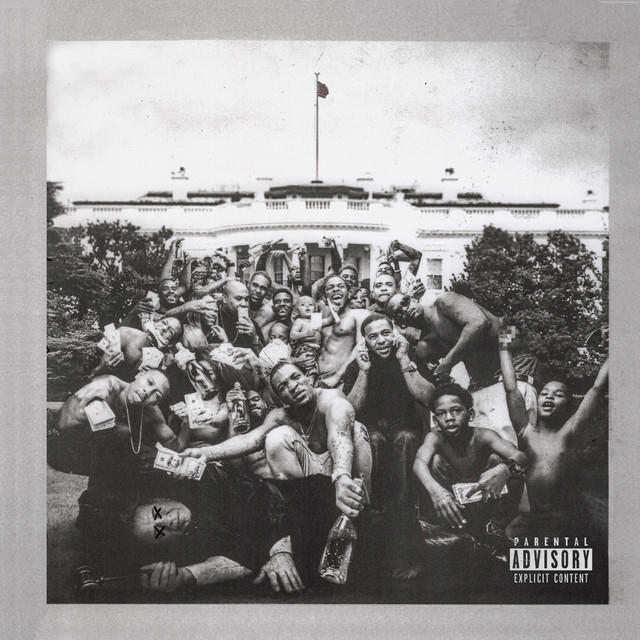

Still, Lamar’s continued interest in jazz as well as jazz artists of his time is extremely apparent on his latest album To Pimp a Butterfly (2015), which some keen listeners have astutely pointed out could be considered a jazz album in and of itself. The album features a virtual who’s who of “next generation” artists—Robert Glasper, Bilal, Lalah Hathaway, Kamasi Washington, Thundercat, Ambrose Akinmusire, Ronald Bruner, Jr., Robert Searight, and Chris Smith—who contribute greatly to the album’s distinct musical qualities, which have been extremely well-received by fans and critics. Greg Tate, for instance, writes with great insight in a powerful and thoughtful essay, “The Compton MC's second major-label album is a masterpiece of fiery outrage, deep jazz and ruthless self-critique” (2015).

It is yet to be seen what will come of the new music and artists of our time in both jazz and hip hop and how they will be discussed and interpreted by future generations. However, something exciting is happening that is already quite worthy of consideration, discussion and debate. My personal hope is that these current artists and their music continue to make strong impacts and inroads and to cover more ground in a continuum rooted in rich African American expressive art forms and history. The declarative phrase, “We got the jazz,” expressed by young hip hop artists was a reverent nod to the past and certainly foretelling of today. It continues to beg the question: who’s got next?

Notes

[1] I am currently unaware of any developments or outcomes regarding this case.

Bibliography

“About.” Revive Music. Accessed April 9, 2015. http://revive-music.com/about/.

Deshpande, Jay. “Jazz Pianist Robert Glasper on His Role in Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly.” Slate. March 27, 2015. Accessed March 30, 2015. http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2015/03/27/kendrick_lamar_s_to_pimp_a_butterfly_robert_glasper_on_what_it_was_like.html.

Ellis, Raydar. Personal communication with the author. April 2, 2015.

“Kendrick Lamar's 'To Pimp a Butterfly': A Track-by-Track Guide.” Rolling Stone. March 16, 2015. Accessed March 17, 2015. http://www.rollingstone.com/music/features/kendrick-lamars-to-pimp-a-butterfly-a-track-by-track-guide-20150316.

Mitchell, Gail. “Kendrick Lamar Collaborator Bilal on 'To Pimp a Butterfly': 'A Lot of This Is Kendrick's Genius'.” Billboard. March 17, 2015. Accessed March 17, 2015. http://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/the-juice/6502408/kendrick-lamar-bilal-to-pimp-a-butterfly-interview.

Reyes, Dan Michael. “5/12: Revive Big Band Live at the Blue Note Jazz Club.” Revive Music. April 29, 2014. Accessed April 8, 2015. http://revive-music.com/2014/04/29/revive-big-band-live-blue-note/.

--------. “Kendrick Lamar: To Pimp A Butterfly – Meet the Musicians Who Made the Album Possible.” Revive Music. March 17, 2015. Accessed March 17, 2015. http://revive-music.com/2015/03/17/kendrick-lamar-pimp-butterfly-meet-musicians-made-album-possible/.

Schloss, Joseph G. Making Beats: The Art of Sample-Based Hip Hop. Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004.

Stewart, Earl and Jane Duran. “Black Essentialism: The Art of Jazz Rap.” Philosophy of Music Education Review 7, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 49-54.

Tate, Greg. “To Pimp A Butterfly.” Rolling Stone. March 19, 2015. Accessed March 21, 2015. http://www.rollingstone.com/music/albumreviews/kendrick-lamar-to-pimp-a-butterfly-20150319.

Williams, Justin A. “The Construction of Jazz Rap as High Art in Hip-Hop Music.” The Journal of Musicology 27, no. 4 (Fall 2010): 435-459.

Wood, Aja Burrell. “Kris Bowers Covers Kendrick Lamar’s 'Rigamortus.'" Revive Music. February 25, 2014. Accessed April 2, 2015. http://revive-music.com/2014/02/25/kris-bowers-covers-kendrick-lamars-rigamortus/.

Aja Burrell Wood is a Harlem based ethnomusicologist from Detroit who teaches African American music at Brooklyn College Conservatory of Music and The New School. Her work includes research on musical community amongst black classical musicians, jazz in the digital era, music and civic engagement in Harlem, and other related genres of the African Diaspora such as blues, hip hop, soul and West African traditions. In the field of arts presenting, she has worked with Wynton Marsalis Enterprises, Dianne Reeves, Revive Music Group and Hot Tone Music. She is currently working to complete her doctorate at the University of Michigan, School of Music, Theatre & Dance.