Chilean Cacerolazo: Pots and Pans, Song and Social Media to Protest

Chilean Cacerolazo: Pots and Pans, Song and Social Media to Protest

Figure 1. Student Strike in 2012. Image from Creative Commons.

Introduction

The fall of 2019 was punctuated by a weeks-long series of demonstrations in Chile that began by denouncing an increase to public transportation costs and erupted into a national movement. The price hike was the tipping point for protestors to condemn decades worth of ineffectual policies by political administrations that had detrimental impacts on Chilean working and middle classes. Consequences included increasing economic vulnerability, high-income inequality, a failing health infrastructure, and an inadequate pension system (Viñas and Céspedes 2020).

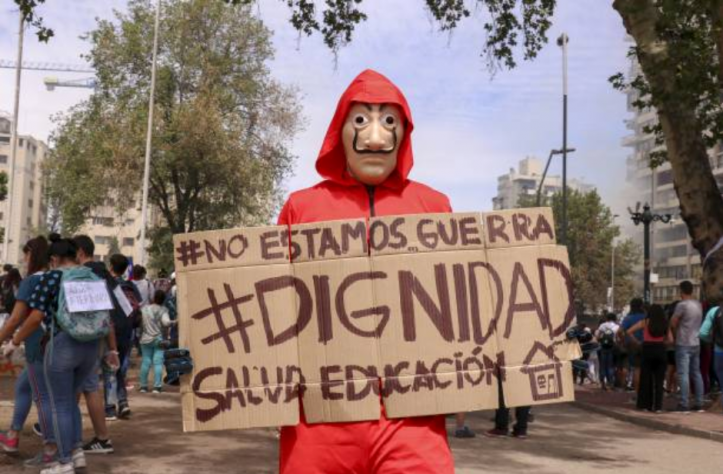

Chilean students whose secondary and post-secondary educational pursuits, and young professionals whose work trajectories have been punctuated by socially and economically disappointing neoliberal policies and a consolidation of wealth in the upper crest, led the charge in this wave of what some outlets labeled as the Chilean Primavera Latinoamericana (Latin American Spring) uprisings (Faiola and Krygier 2019, Levitsky and Roberts 2011). Of the many protests that occurred between 2011-2019 as part of the Latin American Spring, October 2019 is of particular interest here for the ways in which Xennial, Millennial, and Generation Z protestors – generations that have come of age during Chile’s transition from monetarism to neoliberalism, dictatorship to democratic republic – implemented three tools to achieve widespread coordination and consolidate an impactful national presence:[1] the pots and pans banging tradition of cacerolazo, song, and hashtagging (#).

I will begin by briefly touching on the tradition of cacerolazo in a Chilean context. Next, I will expound upon how music has long played a role in the Chilean peoples’ fight for recognition and socio-political change. Such a tradition laid the stage for popular social justice rapper Ana Tijoux to release the politically charged single “#Cacerolazo” and for it to become an on- and offline rallying cry for the 2019 dissent. Lastly, I will explain how the hashtag in the song’s title meaningfully connected the song to the newer 21st-century phenomenon of online (social media-based) participation bleeding into actual offline “real world” action.

Historical Context for Pots-and-Pans Protesting in Chile

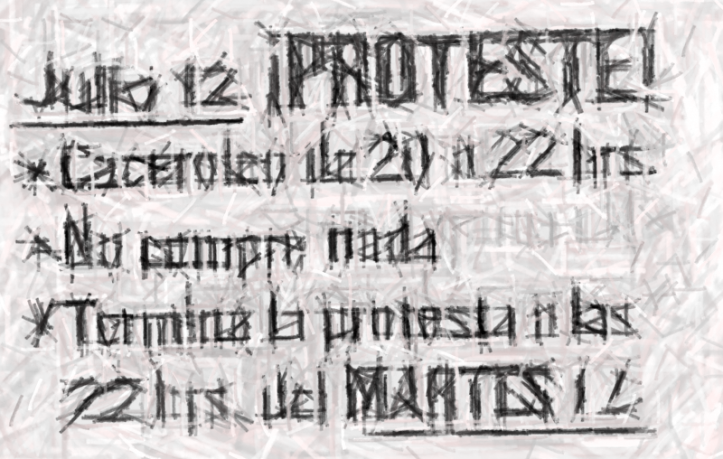

Figure 2. Flyer for third round of national protests on July 12, 1983 in Chile. Image from Creative Commons.

A fixture in Latin American protests for decades, cacerolazo (or caceroleo and cacerolada) involves the banging of pots, pans, lids, and the like to accompany shouted or sung verbal refrains at a demonstration. In Chile, the first large scale appearance of cacerolazo was in 1971 to protest food shortages and the ever-increasing “household economic stress” as the nation’s economy teetered towards a severe depression (Snider 2012). Women in particular were frequent cacerolazo actors, beating pots and pans to draw attention to the empty bellies of their families and children, to having no food with which to fill their pots, and to the lack of large-scale assistance to mitigate rampant shortages of basic essentials (Snider 2012).

A spontaneous, loud, and free form of voicing dissent, cacerolazo had solidified its presence in the Chilean protest scene by 1973. After authoritarian dictator Augusto Pinochet assumed power, public political activity became a dangerous venture, thus quieting widespread cacerolazo until the 1980s when a period of economic crises ushered them back onto the scene. By the end of that decade, the consequences that the economic meltdown had on institutions like education, the agrarian sector, health care, and housing reverberated well into the 2000s. Wages had fallen, unemployment rates simmered at a constant high, pensions were vastly insufficient, and a variety of social programs were eliminated, creating an environment in which social, political, and economic tensions smoldered as a constant backdrop.

For those coming of age in the midst of such turmoil, voicing dissatisfaction and demanding reform had become an increasingly urgent humanitarian undertaking and a vital act to the well-being of Chile as a developed nation (Labarca 2016, Viñas and Céspedes 2020). 2006, 2011, and 2013 were punctuated by protests in which cacerolazo was significantly utilized so that discontent could not be ignored, and these were among the first demonstrations in the millennium in which students specifically led the charge. The Xennial, Milennial, and Generation Z demographics had intimately experienced the fallout since previous decades: “desde 1980 la educación escolar municipal ha tenido una debacle ininterrumpida, y ha quedado en un claro estado de abandono, con mala infraestructura y dudosa calidad” (“since 1980 municipal school education has experienced an uninterrupted debacle, and has been left in a clear state of neglect, with poor infrastructure and questionable quality”) (Labarca 2016: 610).

It was not just municipal primary and secondary schooling that suffered. During this period many jobs were consolidated into the private sector. Training, professional credentials, and degrees were requisite to be a competitive candidate, but the cost of university coupled with other expenses associated with post-secondary schooling (housing, transportation, supplies, etc.), was prohibitive for many and economically punishing for most. By the early 2000s, of those who were able to matriculate, seven out of every 10 students were the first in their family to enroll in university studies, but 84% of families and students themselves financed the expense of such “educación superior” (post-secondary education) (Labarca 2016: 610-611). This is significant since post-secondary education in Chile is higher than most of its Latin American peers while government spending on education is among the lowest in the world (Labarca 2016: 611, Atria 2012). As Labarca notes, “Chile cuenta con los estudiantes universitarios más endeudados del mundo, dado que la relación entre la deuda total en comparación con el ingreso anual como profesional llega a 174%” (“Chile has the most indebted university students in the world, given that the ratio of total debt compared to annual income as a professional reaches 174%”) (Labarca 2016: 611, Atria 2012).

The result has been “una creciente segregación” (“a growing segregation”) between a minority with access to achieve a modicum of social and economic mobility against a majority who cannot (Annunziata and Gold 2018, Barozet and Fierro 2011, Labarca 2016). The rift between these two groups consists of a 237% difference in annual wages, making “Chile the country with the second highest wage disparity of this sort, with only Brazil having a wider margin” (Cocker 2017).

Song-Led Protest Culture

Figure 3. A musician raises his instrument in the air during a "symphonic tribute" to Chilean musician Victor Jara in Santiago, on November 10, 2019. Photo by Claudio Reyes/AFP via Getty Images.

It is within such a context that the 2019 decision by President Sebastián Piñera to raise metro fares by 30 pesos (roughly 3.6 cents in USD) served as the tipping point that exploded into a series of student-led protests that tackled income inequality, the disintegration of Chile’s public health care system, the high costs of education and housing, and the insufficient pension system (Viñas and Céspedes 2020). The protests on October 18, 2019 are particularly of interest for this discussion as they led to a declaration of a national state of emergency (an escalation that had not previously occurred and that drew global attention) (Viñas and Céspedes 2020). The repressive response by the government and military to what began as a peaceful protest inspired the release of Tijoux’s rap “#Cacerolazo” in which the motivations and sentiments behind the student movement are explicitly outlined (and in such a way that links 2019 to a long tradition of Chileans leveraging loudness to not be minimized), and why an overall feeling of #ChileSeCanso (#ChileIsTired) was seized by demonstrators refusing to concede.

Tijoux follows a rich tradition in Chile of musicians being at the forefront of leading resistance against government violence and repressive policy. The Nueva Canción Chilena (Chilean New Song) of the 1950s and ’60s often combined socially charged lyrics with traditional melodies and Andean instrumentation. While there is much that has been written about New Song, Víctor Jara is one of the most influential contributors to the Chilean take on the genre, and for making it one that progressive and young Chileans continue to flock to decades after his death. His lyrics and performances were overt criticisms of the political right and the Pinochet regime, an aggressive outspokenness that led to his torture and murder in 1973 for writing subversive songs. Instead of intimidating his fans and those who identified with the social causes he had taken up, Jara’s assassination immortalized him and his music as a martyr and beacon for the left.

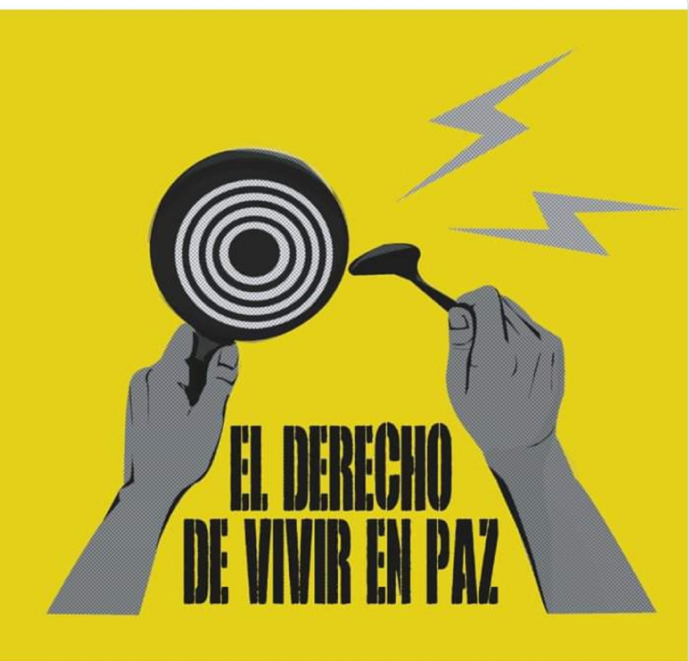

Four decades later as part of the 2019 student-led protests, “Jara remain[ed] a relevant voice of national kinship and empathy” (Donohue 2019). His music continued to be a symbol for resistance so much so that his song, “El Derecho a Vivir En Paz” (“The Right to Live in Peace”) was re-released as a “reimagined” compilation in late October 2019 updated to reflect the crisis and causes of the protests and featuring the voices and instrumental accompaniment of more than thirty popular Chilean musicians (Donohue 2019).

The re-released version of the song was accompanied by the hashtag #elderechodevivirenpaz resulting in an even more widespread sharing of not just the song but the sentiment in a national context that generated many tens of thousands of Twitter posts. Videos of protestors belting the lyrics saturated social media newsfeeds as Chileans around the country and of all ages rallied around the cause.

Oppositional Resistance with Rap

Figure 4. Artwork for Human Rights in Chile by Tomiko Takino. Image from Twitter.

A wave of music-fueled oppositional resistance swept through Chile in the fall of 2019 as protests continued and the draconian government response increased. Tijoux, a social justice rapper with a reputation for confronting sensitive socio-political issues head on, jumped on the bandwagon. On October 20, 2019, two days after the Chilean government declared a national state of emergency and implemented a military-enforced curfew that many felt harkened back to the dictatorial days of Pinochet, Tijoux released her single, “#Cacerolazo”.

The rap is simple in form consisting of Tijoux’s voice accompanied by the sound of a solo pot or pan being struck and a single beat. The music video offers a visual montage of protestors on the streets amidst fires, tanks, and armed individuals. Images of police kicking and dragging protestors, of the latter fleeing tanks, of others banging pots next to a soldier’s face, of a city burning around the chaos, loop as Tijoux begins to rap.

For the first nine seconds, the title is front and center on the screen in bold letters. As the video ends, it stands alone against a black backdrop as the sound of sirens fades. The vast majority of Chilean youth would recognize the cue embedded in the title to jump on social media to search and peruse content associated with the # handle, and subsequently like, post, comment, and forward it within their networks. It acts as a pint-size method to reference cacerolazo as an action with strong historical and cultural ties that bonds Chileans while the hashtag injects a Xennial/Milennial/Generazation Z signal, a new-age cacerolazo that offers the possibility to participate beyond the physical outside world among a virtual, interconnected, and instantaneous battleground as well.

The song begins with a spoken verse as if Tijoux were a news reporter advising the listener:

En doscientos metros In two hundred meters

Gira a la derecho Turn to the right

Y corre conchetumare And run motherfucker

Que vienen los pacos The police are coming

This is followed by rhythmic repetition of the word cacerolazo, perfect for a pot-and-pan banging accompaniment if the listener were so inclined. The lyrics continue:

Quema, despierta Burn it, wake up

Renuncia, Piñera Resign, Piñera

Por la Alameda, Because la Alameda,

Es nuestra La Moneda Is our La Moneda

Cuchara de palos, Wooden spoons,

Frente a tus balazos Facing your bullets

¿Y al toque de queda? And the curfew?

¡Cacerolazo! Cacerolazo!

Calling on Chileans to rise up and for President Piñera to resign, Tijoux states that the “Alameda”--one of the main streets in the capital city of Santiago and a principal gathering point for protestors--is their version of “La Moneda”, the presidential palace that was bombed in 1973 as part of the military coup d’etat that ended with Pinochet assuming power. It inverts the violence used by the military against the government during the ’70s with that which the government and military was opting to enact against protestors in 2019. The bombing of La Moneda is a significantly symbolic event marking the forced transition from the (failed) socialism of Salvador Allende to the (worse) dictatorship of Pinochet. Tijoux is declaring that the events of these protests perhaps mark another turning point in Chilean history by drawing a parallel between the events of La Moneda in the ’70s with what was occurring along the Alameda corridor in 2019.

“Wooden spoons” against “bullets” paint the picture of the unpretentious citizen carrying nothing more than the humble cutlery from their home to face an aggressor far more severely equipped. As enthusiasm for demonstrations and a collective call for leaders to acknowledge what was behind protestors’ actions refused to abate, Piñera enacted a curfew under the premise that Chile was at war. This declaration quickly became “un error de proporciones en términos de comunicacionales” (“a substantial error in terms of media relations”) and was met with intense objection for how it demonized protestors who could not, and did not intend to, compete with a war-like, military-led response (Viñas and Céspedes 2020). The skewed proportion of response fueled protestors and supporters to even more fervently declare “¡Cacerolazo!” against what was felt to be the ridiculous and belligerent government response.

There is a palpable sense of frustration on behalf of the student-led movement that the extreme measures being taken to silence their ventures was more of the same behavior that the Chilean people had long experienced. Decker, referencing African-American rap trends in the U.S., notes that “while political rap artists are not politicians, they are involved in the production of cultural politics – its creation, circulation, and interpretation- which is tied to the struggles of working-class blacks and the urban poor” (Beighey and Unnithan 2006: 134). The same can be observed with Tijoux’s rap and the Chilean context in the next stanza:

No son 30 pesos It’s not 30 pesos

Son 30 años, It’s 30 years,

La Constitución y los perdonazos The Constituion and the pardons,

Con puño y cuchara With a fist and spoon

Frente al aparato Facing the system

Y todo el estado, And all of the State,

¡Cacerolazo! Cacerolazo!

The proposed thirty peso increase in metro fare that sparked the outpouring of response is not the root cause of the protestors’ demands, but rather the thirty years leading to 2019 during which the viability of Chile’s economy, education, health systems, and more became untenable. The “Constitución” references the governing parameters outlined by Pinochet that were felt to be outmoded, ineffective, and limiting of freedoms, while “perdonazos” alludes to changes in Chilean tax law that had predominately benefited the nation’s wealthiest (further widening class gaps and impeding socio-economic mobility for the majority of Chileans).

Tijoux champions how she and her comrades – armed with only a fist (in solidarity) and a spoon (in nonviolence) – have confronted a system that appeared to work largely against the Chilean people. Indeed, challenging an entire governing body as a united cacerolazo-imbued force is the theme of the last stanza as Tijoux counsels her peers:

Escucha, vecina Listen, neighbor

Aumenta la bencina Add more fuel

¿Y la barricada? And the barricades?

Dale gasolina Pour on the gas

Con tapa, con olla With lids, with pans

Frente a los payasos, Facing the clowns,

Llegó la revuelta The revolt has arrived

Y el Cacerolazo With the Cacerolazo

The song continues with the same rhythmic repetition of “cacerolazo” heard in the beginning while a montage loops in the background of politically charged images mixed with videos and photos of young Chileans spiritedly banging pots.

With “#Cacerolazo”, Tijoux firmly places herself within a musical demographic that uses rap as a cultural form “to speak about the loneliness, exclusion, and injustices endured” around her (Beighey and Unnithan 2006: 134). She is leveraging political rap to convey “messages that translate into individual experiences into calls for attention [and action] to oppressive forces” (Beighey and Unnithan 2006: 134). This is even more the case considering that she titles her song with a cultural moniker and a hashtag, cues to act from the most mundane (one’s living room) to the more extreme (mid protest march) with a wordless method (pots and pans) that her Chilean compatriots would immediately recognize in solidarity.

Conclusions

Figure 5. Protesters gather in Santiago to inflict improvements in the constitution and resignation of President Sebastian Piñera on the fifth day of social riots. Photo by Muhammed Emin Canik/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images.

Oppositional musical resistance that breaks into mainstream popularity establishes a collective basis within, where calls for equality and change germinate. Social media activity, like hashtagging pint-size slogans (#Cacerolazo or #elderechedevivirenpaz) that echo catchy and memorable lyrical catchphrases, further intensify this process and increases their visibility and spread. For the user, which under pervasive algorithmic Internet and social media culture would represent an increasingly larger percentage of people, immediate recognition of what is meant behind the hashtag slogan, or rather the economic, political, social, racial posture it reflects, operates as a type of “blueprint for social resistance,” in this case the sentiment of unity to rally and raise cacerolazo (Beighey and Unnithan 2006: 135).

Tijoux’s rap (and the #elderechodevivirenpaz hashtag associated with the re-mix of Jara’s song) illustrate the “influencia de los nuevos medios de comunicación digital y las redes sociales online en los procesos…de movilización ciudadana” (“influence of new modes of digital communication and online social networks in the process of citizen mobilization”) (Annunziata and Gold 2018: 461). The intersection and level of spontaneity promulgated by the intertwining of song composition, performance, and mass distribution, along with the phenomenon of instantaneous sharing provided by hashtagging and social media, represent a convergence that produce a “magnitud de acontecimientos [que] no hubiera sido possible con un formato organizativo tradicional” (“magnitude of events that would not have been possible with a traditional organizational format”) (Annunziata and Gold 2018: 477). Through the on- and offline meeting of worlds it was possible for protestors and fans to “promocionarla y hacerla propia” (“promote it [the cause] and make it their own” (Annunziata and Gold 2018: 477). It also made it so the student-led demands infiltrated every fiber of socio-political fabric at a pace and level that eventually resulted in Chilean leaders conceding to offer the public a chance to vote on replacing the Constitution in April of 2020.

Bibliography

Annunziata, Rocío and Tomás Gold. “Manifestaciones ciudadanas en la era digital: El ciclo de ‘cacerolazos’ (2012-2013) y la movilización #niunamenos (2015) en Argentina”. Desarrollo Económico 57, no. 223 (2018): 461-485.

Atria, Fernando. 2016. La mala educación: ideas que inspiran al movimiento estudiantil en Chile. Santiago de Chile: Catalonia/Centro de Investigación e Información Periodística.

Barozet, Emmanuelle and Jaime Fierro. “The middle class in Chile. The characteristics and evolution 1990-2011”. KAS International Reports 12 (2011): 25-41.

Beighey, Catherine and N. Prabha Unnithan. “Political Rap: The Music of Oppositional Resistance”. Sociological Focus 39, no. 2 (2006): 133-143.

Cocker, Isabel. “Chile’s University Tuition Fees amongst world’s highest”. The Santiago Times. September 15, 2017. https://santiagotimes.cl/2017/09/15/chiles-university-tuition-fees-amongst-worlds-highest/

Donohue, Caitlin. “Following Tradition, Chilean Musicians Lead in Anti-Inequality Protests”. Remezcla. October 23, 2019. https://remezcla.com/features/music/chilean-artists-lead-protests/

Faiola, Anthony and Rachelle Krygier. “How to make sense of the many protests raging across South America”. The Washington Post. November 14, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/a-government-chased-from-its-capital-a-president-forced-into-exile-a-storm-of-protest-rages-in-south-america/2019/11/14/897f85ba-0651-11ea-9118-25d6bd37dfb1_story.html

Labarca, José Tomás. “El ‘ciclo corto’ del movimiento estudiantil chileno”. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 78, no. 4 (2016): 605-632.

Levitsky, Steven and Kenneth M. Roberts. 2011. The Resurgence of the Latin American Left. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Snider, Colin M. “A Brief History of Pots and Pans”. Americas South and North. June 8, 2012. https://americasouthandnorth.wordpress.com/2012/06/08/a-brief-history-of-pots-and-pans/

Viñas, Silvia and Álvaro Céspedes. “Chile, una tregua por la pandemia”. El Hilo. Podcast Audio. April 24, 2020. https://elhilo.audio/podcast/coronavirus-chile/

Kaitlin E. Thomas, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Spanish at Norwich University. Her research delves into U.S. and Latino/a identities that are resulting from trans-border cultural and national fusion, (un)documented Latino/a immigration, and music as a site for resistance.

[1] Xennials were born between 1975-1985, millennials between 1980-1994, and generation Z between 1995-2012.