The Drumming of Traditional Ashanti Healing Ceremonies

Biography

Ben Wilson is an undergraduate student of Recreation Management Youth Leadership at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. In addition to recreation, his interests include music, anthropology, and medicine.

Abstract

This paper stems from a field study I conducted in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, West Africa from May to July of 2004. It discusses the drumming that accompanies traditional healing ceremonies of the Ashanti people – covering both the identification of specific rhythms that are typically played in healing ceremonies and the purposes of those rhythms.

All photographs courtesy Eric Ashford 2004

Introduction

Traditional African healers and healing ceremonies have been studied for years in an attempt to better understand the peoples and cultures. Music has been shown to have a significant role in the healing ceremonies of many African peoples, from the Zar cults of Ethiopia and Sudan (Boddy 1989), to the Tonga of Zambia (Colson 1969), the Shona of Zimbabwe (Gelfand 1964), and the Malagasy of Madagascar (Emnoff 2002). In the words of Agordoh, “No one who has visited a scene of public worship in Africa can be in doubt that one of the attributes of the gods is that they are music-loving gods” (Agordoh 1994, 38). Friedson stated that many African peoples “…experience sickness and healing through rituals of consciousness-transformation whose experiential core is music”(Friedson 1996, xi).

Little, if any, research has been published on the music of traditional healing ceremonies of the Ashanti people of Ghana, West Africa. In an attempt to lay the groundwork for further research on Ashanti shrine music, I conducted a field study from May to August of 2004 in the district of Ashanti-Mampong in central Ghana. This paper discusses specific purposes of Ashanti shrine drumming and explores some of the specific rhythms that are typically played at shrines near the town of Ashanti-Mampong.

top

Ashanti Religious Ideology

In order to understand the role of Ashanti shrine music in healing, one must first have an understanding of basic Ashanti religious ideology.

Like people of Western religions, the Ashanti believe in one all-powerful, all-knowing god who created all things (Bannerman-Richter 1982). According to Ashanti beliefs, however, this god, known as Onyame, has withdrawn himself from the world and now has no direct contact with humans (Rattray 1923).

Just below Onyame in rank is a large group of lesser gods who have contact with both Onyame and man. These gods, known as abosom, are similar to humans in that they have a variety of interests and personalities. Unlike humans, however, the abosom have special knowledge and power in the spiritual realm, where they live (Rattray 1923). Along with their home in the spiritual world, abosom are usually associated with a physical place or object (such as a village or a river) which could be considered their earthly dwelling. Shrines are often built at locations near these abosom dwellings to provide a way for humans to contact the abosom (Bannerman-Richter 1982).

The human medium who has connection with both the abosom and the physical world is the okomfo – the Ashanti traditional healer (Rattray 1927). An okomfo typically lives at or near a shrine dedicated to a particular obosom (singular of abosom) or group of abosom. Ceremonies are held regularly at these shrines, where an okomfo becomes possessed by an obosom and, acting as the obosom, consults with people about how to solve problems they are facing (Twumasi 1972).

Traditionally, Ashanti people believe that many problems, whether spiritual, social, or physical, have spiritual roots. For example, if an Ashanti person fell sick unexpectedly, he or she would probably not attribute the illness to any type of biomedical problem. Rather, he or she would probably feel that the illness had a spiritual cause, like a curse from a relative or a punishment from the gods for misconduct (Twumasi 1975). To the Ashanti, even financial problems, like bad luck in business, often have spiritual causes (Bannerman-Richter 1982). Because of this belief, the Ashanti will often turn to the abosom, rather than a psychologist or medical doctor, for solutions to their problems (Twumasi 1975).

With this basic background about Ashanti religious ideology, one can better understand the proceedings of a typical Ashanti shrine ceremony.

Shrine Ceremony

There is some variability in how a shrine ceremony is carried out, but the following description of a typical shrine ceremony is derived from my field study in villages near Mampong (especially the village of Penteng), and is comparable to ceremony proceedings observed by other researchers, including Twumasi (1972) and Nketia (1957).

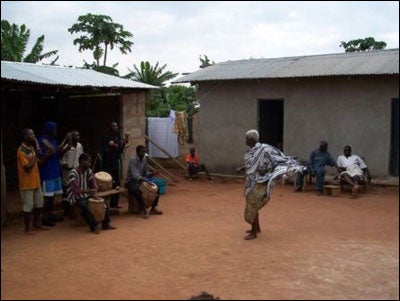

Plate 1: The Drummers at Penteng

At around ten in the morning on a healing day, the okomfo, shrine officials, shrine musicians, and some of the elders of the village gather at the shrine compound in preparation for the ceremony. The okomfo, shrine officials, and elders sit on wooden chairs and stools in the shade of a tree, while the musicians, usually about five male drummers and about seven female singers and rattle shakers, take their seats on wooden benches under a small structure built for shade (Plate 1). There, the musicians begin drumming and singing to announce that the okomfo will soon perform the healing ceremony.

Answering the call of the drums, villagers interested in consulting with the abosom enter the shrine compound, take a small wooden square with a number on it, and sit down to wait on wooden benches behind the musicians, who play periodically.

After most of the patients have entered the compound and taken their seats, the drummers and singers start to play again as the okomfo, dressed in a white robe, moves across the compound and sits down on a metal-studded wooden chair, facing the musicians. The musicians begin playing more vigorously, and, after a short time, the okomfo kicks off his sandals, signifying the obosom has entered into him. Once the okomfo is possessed, one or two shrine officials stand and escort him into a small building to change into a different costume, depending on which obosom has possessed him. After the okomfo is inside the building, the drums and rattles are silenced, and the women sing a short call and response song.

After a few minutes, the okomfo emerges from the building dressed in the clothing of the obosom by whom he is possessed. He is accompanied by shrine officials, one of whom carries a bowl of white talcum powder, which the okomfo periodically sprinkles on objects or on the ground in front of him. The okomfo and shrine officials gradually make their way across the compound to another small building, which acts as a consultation room, stopping along the way to pour a libation of alcohol on the ground to the obosom and to the ancestors of the okomfo.

Once the possessed okomfo and his linguist (who translates for patients when the obosom possessing the okomfo does not speak the local language) enter the consulting room and are seated, shrine officials signal to the patient who holds the first number to enter the room with the okomfo and linguist. There, the patient describes the nature of his or her problem, whether it be physical, social, or spiritual. Then the obosom, acting through the okomfo, tells the patient the remedy to his or her problem, which often entails using herbal medicines and/or sacrificing a patient’s animal or money to the obosom or to an evil spirit that is causing the problem. Once the okomfo has consulted with each of the patients at the shrine, the obosom leaves, and the okomfo emerges from the consulting room, usually exhausted.

After the ceremony, shrine officials and the okomfo help the patients follow the instructions given by the obosom (for example, sacrificing a chicken to the gods or taking an herbal remedy). After these instructions are followed, the spiritual cause underlying the person’s problem is considered removed, and therefore the illness itself will soon be alleviated as well.

The Role of Shrine Music

In discussing shrine music, this paper does not attempt to cover details of the mechanics of the musical production, nor does it attempt to discuss the lyrics of each of the shrine songs. Rather, my focus is on the purposes of shrine rhythms in a social and religious context, including the role of drumming in general within a shrine ceremony and a report of specific rhythms commonly played at shrines.

According to Nketia (1963), there are three fundamental modes of drumming among the Ashanti: signal mode, speech mode, and dance mode. Although the purpose of the dance mode of drumming is mostly recreational, the signal and speech modes are played strictly for communication. Unlike typical drumming in Western cultures, Ashanti drumming is often used as a means of communication.

The idea of using drums to communicate is best exemplified by the atumpan – the Ashanti “talking” drums. Atumpan come in pairs – one drum with a high tone and the other with a low tone. These two drums are played with “a steady flow of beats, often lacking in regularity or phrasing” (Nketia 1963, 28) to mimic the highs and lows of the local Twi language, which is a tonal language. Although many people of the younger generation can’t understand the words being played on the atumpan, much of the older generation can understand the drums as well as they can understand someone speaking to them.

Atumpan are used for communication in various social situations among the Ashanti, from conveying a message to a dancer in the middle of a dancing ring to calling the school children back to class after their break (Hood 1964).

One very practical purpose of shrine drumming, in keeping with the communicative nature of Ashanti drumming, is to announce to everyone within hearing that there will soon be a healing ceremony at the shrine. When I asked a shrine official why drumming is included in the shrine ceremony, he replied that the sound of the drumming “goes very far from the town. If someone is living far, when he hears the noise, he knows something is going on at the shrine” (Gyasi 2004).

Shrine drumming is not only played to communicate with people; it is also played to communicate with the gods. When I asked okomfo, musicians, and other villagers at the shrines about the purpose of music in the ceremonies, the almost-universal answer was that the music calls the obosom to possess the okomfo. Literature on the topic also clearly states that music is played in healing ceremonies to call the gods (Twumasi 1975; Bannerman-Richter 1982). Considering that abosom are believed to be human-like, and drums are used as a beckoning call for humans, it’s no surprise that drumming is also used to call abosom.

Although the inclusion of drumming in shrine ceremonies is preferred by the okomfo, it is not an indispensable part of the ceremony. Because of the difficulty and cost for the musicians to leave their farms to gather at the shrine, okomfo at most shrines include drumming on only some of the days that ceremonies are held. Some shrines cannot afford drums or the cost of hiring drummers at all and therefore almost never include drumming in their ceremonies. Where drums and/or drummers are not available, shrines will often use other means to call the gods, including ringing a small bell or tapping a rock rhythmically on the ground.

The question then arises: if drumming is not essential to the ceremony, why include it at all? When I discussed the matter with one particularly helpful okomfo, Nana Gyasi Obeng from the village of Penteng, he told me that the music helps the abosom to work hard. He also explained that the gods, like humans, have different tastes in music and will be more likely to come, and come with more strength, if they hear music they like (Obeng 4 June 2004). Gyasi’s comments are consistent with Agordoh’s statement that “each god has its own type of music, which interests him more or which is of his own taste,” (Agordoh 1994, 39) and with Nketia, who said that among the Ashanti “gods are supposed to be sensitive to the language of music and would come down to see ‘their children’ if they heard music they liked” (Nketia 1963, 99). A correlation can be drawn between the purpose of shrine music and the purpose of music in the services of many Christian sects. In both situations music is not essential, but it helps create an environment where a deity (the obosom among the Ashanti and the Holy Ghost among Christians) is more likely to come and remain long enough to spread its good influence to the worshippers. Although drumming is not essential at the shrine, it is preferred because it creates an environment where abosom are more likely to come, and come with more strength.

Considering that drumming in healing ceremonies is preferred because good drumming can help the gods come with more strength, the questions may be asked: what constitutes “good” drumming, and what does it mean for an abosom to “come with more strength?”

In answer to the former question, Nana Gyasi said that if the drumming is not good, “[the gods] will come all right, but they will not… do more wonderful things” (Obeng 2005), meaning that the gods will not have as much power to identify the causes of patients’ problems. Although this is a somewhat circular explanation of what constitutes “good” drumming (i.e. if drumming is good, the results will be good; and if the results are good, the drumming must have been good), it is clear that “good” drumming is something that is felt and easily identified by observers, but it is not easily described. It is not uncommon, though, to have difficulty describing what exactly makes music “good.” For example, lovers of jazz may be able to recognize a good concert when they see it, but it would usually be very difficult for them to pin down exactly what made it “good.” Good jazz musicians would probably be described as having “good energy,” or playing “with soul.” Similarly, it’s hard to describe exactly what makes Ashanti shrine drumming considered “good.” Nevertheless, there is a clear distinction, recognized by almost all observers, between good and poor drumming. It could be said that when the shrine musicians are playing with “good energy,” or “with soul,” then the obosom will be more likely to come, and come with strength.

In answer to the question about what it means for an obosom to come with strength, Nana Gyasi explained that when the gods have more strength, they are better able to identify the cause of a patient’s problem. As a result, patients will come away from the shrine with their problems solved, and they will, in turn, tell other people to go to the shrine because the god there is a “very powerful god,” and the shrine will continue to increase in popularity (Obeng 2005). Therefore, the strength of a god could be determined by noting how many people are healed after visiting the shrine, or by observing the popularity of the shrine. If it is the case that effective healing is closely tied to the strength of a god, and the strength of a god is closely tied to the quality of the drumming, then there is a direct link between the quality of music at a shrine and an okomfo’s ability to heal patients.

Plate 2

A few examples may help illustrate the role of drumming in the ceremonies. On June 20, 2004, I observed a ceremony performed by Madam Sewaa, an okomfo at a shrine in the small village of Daaho. The ceremony started off fairly typically – the musicians started playing, and Madam Sewaa began dancing and twirling around the compound (Plate 2). After a short time, the obosom possessed Madam Sewaa, and she walked across the compound, entering a small room. After a few minutes she emerged, dressed as the obosom by whom she was possessed (Plate 3). The drumming picked up again, and Madam Sewaa resumed her dancing, running, and spinning around the compound. From time to time she walked over to the drummers and said something to them. Each time she did this, the drummers would stop and either adjust the rhythm or change rhythms entirely. When the drummers started again, Madam Sewaa would resume dancing, but each time she danced with a little less energy (Plate 4). Finally, Madam Sewaa, looking completely worn out, walked over to the drummers and told them to stop. Then she slowly walked over to me and explained, through the translator, that the drummers were not playing well enough, so she had become very tired and had to leave. After her explanation, Madam Sewaa returned to the small room, and the ceremony was over. This example illustrates Gyasi’s comments: the expected good drumming would have been strengthening, the lack of good drumming had the opposite effect. Because the music was not good, the okomfo could not work hard, and the obosom left.

Plate 3

Plate 4

An example from an observation in Kofiase on June 20, 2004, helps demonstrate that drumming, although it not essential to shrine ceremonies, is still generally preferred by okomfo. The okomfo at the shrine in Kofiase, Nana Sekyere, could not afford drums or the cost of hiring drummers. Although he could have performed ceremonies without any drumming, he chose to make up for the lack of drums with basic technology. Nana Sekyere bought a small cassette recorder and recorded some typical shrine rhythms onto a tape. During ceremonies, while he was preparing to become possessed by one of the gods, Nana Sekyere would play his tape recording of the shrine rhythms. This recorded drumming, though not presented in a typical way, still served its purpose in Nana Sekyere’s ceremony – it called down the gods. When drums or drummers are not available at shrines, okomfo like Nana Sekyere still prefer to include drumming in their ceremonies – even if it requires presenting the drumming in a creative, less-traditional way.

With an understanding of the general purpose of drumming in shrine ceremonies, one can begin to explore some of the specific rhythms performed at shrine ceremonies and the reasons for their inclusion in the shrine repertoire.

Different social groups among the Ashanti often have specific drum rhythms associated with them (Nketia 1963). The rhythms typically played by religious associations at shrines are known among the Ashanti as “okomfo twene,” which literally means “okomfo drums.”

Identification of Shrine Rhythms

The set of traditional okomfo twene rhythms is dynamic. There is not an exact number of rhythms, and there are not any specific rhythms that are set in stone as the only traditional rhythms of okomfo twene. The master drummer at the shrine in Penteng explained that a shrine drummer will often learn rhythms which have been proven through time to be effective in calling the gods from his predecessors. But a drummer may also create new rhythms, which, if they are found to be effective, can be added to the repertoire of his shrine (Obeng 28 May 2004). He then explained that, during festival periods, okomfo and shrine drummers often visit other shrines and listen to the drumming. If they like a new rhythm they hear, the visiting okomfo and drummers may adopt the new rhythm, thereby spreading it throughout the region.

Because of this open-set format of okomfo twene, the shrine drumming is, as Nketia observed, “remarkably varied in style and in the number of pieces that are played” (Nketia 1963, 93). Nketia then proceeded to list twelve of the rhythms he observed during his fieldwork in the late 1950s. Although there is a wide range of possible okomfo twene rhythms, there are, nevertheless, a few rhythms that have persisted through the years because of their effectiveness in calling the gods. These rhythms could be considered the traditional okomfo twene rhythms of the Ashanti.

I observed multiple shrine ceremonies from six villages near the town of Ashanti Mampong in the Sekyere District of the Ashanti Region of Ghana. These villages included Daaho, Kofiase, Krobo, Kyeremfaso, Penteng, and Sesease (Figure 1). At each of these villages I made video recordings of the drumming during regular shrine ceremonies and ceremonies on Akwasi Day (a religious holiday held to pay respect to the gods (Rattray 1923)). Additionally, I filmed shrine drummers in Sesease and Krobo playing their ceremonial rhythms for me outside of a ritual setting.

Figure 1: A Map of the Mampong Area

Once I had made video recordings from various visits to these shrines, I interviewed both local drummers (Sesease drummers 2004; Penteng drummers 2004; Krobo drummers 2004; Daaho drummers 2004) and emeritus Professor J.H. Kwabena Nketia of the University of Ghana (Nketia 2004) to learn the identification, history, and significance of the rhythms I had recorded. Some of the rhythms could not be identified by local drummers or by Professor Nketia and are therefore probably examples of locally created, non-traditional rhythms. Along with these rhythms, though, there were several traditional rhythms from each of the shrines that were identified by name by both local drummers and Professor Nketia. These rhythms are listed in the following table: (1)

| Daaho | Koflase | Krobo | Penteng | Sesease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Abuko is a traditional Ashanti dance rhythm. It is played during traditional healing ceremonies to help excite and energize okomfo in preparation for their possession by the gods. This audio example of abuko was recorded in Penteng on June 20, 2004.

Adaban is a traditional Ashanti dance rhythm. It is also played during traditional healing ceremonies in preparation for spirit possession. This audio example of adaban was recorded in Sesease on May 24, 2004.

Abofoo is a traditional rhythm of the Ashanti Hunters Association. It is played during traditional healing ceremonies to invite hunting gods to the shrine to possess the okomfo. This audio example of abofoo was recorded in Penteng on June 4, 2004. It was identified by both Nketia and the drummers as the traditional rhythm of the Hunters Association.

Asafo is the traditional rhythm of the Ashanti Warriors Association. It also forms part of the traditional healing ceremony repertoire, but it specifically appeals to warrior gods. This audio example of asafo was recorded in Sesease on May 24, 2004. My informants identified it as the traditional rhythm of the Warriors Association.

The last example is a rhythm that local drummers commonly refer to as highlife (a generic rubric for most modern Ghanaian music). Nketia identified this rhythm as akatape. Akatape is a traditional rhythm of the Ashanti Executioners. Like all the aforementioned rhythms, akatape accompanies traditional healing ceremonies. It propitiates and calls to executioner gods. This audio example was recorded in Penteng on June 20, 2004.

Of all the okomfo twene rhythms, those listed above were the most commonly played at the shrines near Ashanti Mampong. Two of these rhythms, abofoo and adaban, were also documented by Nketia (1963), and are, therefore, examples of rhythms that have persisted through decades as the traditional okomfo twene repertoire. Rhythms similar to abofoo, abuko, akatape, and asafo were recorded in the Akwapim region of Ghana by Kiehl (1999) in the mid-1990’s, (2) thus showing that the okomfo twene rhythms have not only persisted through time, but they are also consistent in various regions of Ghana.

Purposes of Specific Okomfo Twene Rhythms

Agordoh stated, “In addition to the use of songs as a vehicle for worship, it is a means of stimulating the media of the gods to action and keeping them in a condition of ecstasy until the mission of the gods has been fulfilled” (Agordoh 1994, 39). According to the local drummers, the abuko and adaban rhythms, both of which are traditional dance rhythms, are played during the ceremony to excite and energize the okomfo (who are acting as the “media of the gods” as mentioned above by Agordoh). These dance rhythms are especially important in preparing okomfo to be possessed by an abosom and in keeping them energized while possessed.

The remaining three rhythms, abofoo, akatape, and asafo, are all tied to different Ashanti social groups – hunters, executioners, and warriors respectively. Nana Gyasi, the okomfo in Penteng, explained that “the gods are very different – like you. Some of you like bread, some of you like pineapple, some of you like American candies, or whatever” (Obeng 6 June 2004). He went on to explain that the abosom have different tastes in music, and they typically like music with which they can identify. For example, he explained, if an obosom was a warrior and the shrine drummers played a traditional warrior rhythm, the obosom would remember the time he spent on the front lines of battle. This memory would excite him, strengthen him, and entice him to come down and visit the shrine.

Nana Gyasi’s example above provides good information as to why the asafo (warrior) rhythm is played at the shrines. If the obosom living near the shrine was a warrior obosom, the drummers of that shrine would likely play the asafo (warrior) rhythm to excite the obosom and influence him to come down, and come with more strength. The asafo rhythm would also likely be accompanied by some of the traditional dance rhythms like abuko and adaban to excite the okomfo. It follows, then, that shrine drummers playing the abofoo or akatape rhythms would likely be appealing to a hunter obosom or an executioner obosom respectively. The drummers at the shrine in Penteng almost exclusively played the abofoo rhythm during regular shrine ceremonies. When I asked Nana Gyasi which type of abosom live in Penteng, he replied that they are all hunters (Obeng 7 July 2004). Taking all of these things into consideration, I hypothesize that shrine drummers play rhythms from Ashanti social groups because they are appealing to abosom that are identified with those groups.

In summary, there are two general types of rhythms typically played at shrines: 1) dance rhythms used to excite and energize okomfo, and 2) rhythms of social groups used to excite and energize abosom.

Conclusion

This study has shown that drumming is included in healing ceremonies to call both people and abosom to come to the shrine. Shrine drumming also creates an atmosphere where the abosom are more likely to come, and come with more strength. Two general types of traditional rhythms are commonly played at shrines – dance rhythms and rhythms of Ashanti social groups. Dance rhythms are often played at shrines to help energize okomfo and to prepare them for possession. Rhythms of different Ashanti social groups are played at shrines in an attempt to invite abosom who are identified with those social groups to come. Drumming clearly has a significant role in Ashanti healing ceremonies, but further fieldwork should be done to confirm and expand the findings presented in this paper.

1. The okomfo at the shrine in Kyeremfaso rang a small bell to call the gods because there were no drums at the shrine. Kyeremfaso, therefore, is not included in the table.

2. Although the names of the tracks on Kiehl’s compact disc (Kiehl 1999) are not consistent with the names of the rhythms identified in this paper, I assume the tracks on Kiehl’s compact disc are named after the lyrical songs, and not the rhythms. On the compact disc, tracks 3, 5, 10, 13, 15, and 17 have characteristics similar to both the rhythms abofoo and akatape; tracks 8, 12, and 18 are similar to Abuko; and tracks 2, 11, 14, and 16 are similar to asafo.

top

Agordoh, A. A. 1994. Studies in African Music (Revised Edition). Ho: New Age Publication.

Bannerman-Richter, Gabriel. 1982. The Practice of Witchcraft in Ghana. Elk Grove: Gabari Publishing Company.

Boddy, Janice. 1989. Wombs and Alien Spirits: Women, Men, and the Zar Cult in Northern Sudan. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Colson, Elizabeth. 1969. “Spirit Possession among the Tonga of Zambia.” In Spirit Mediumship and Society in Africa, edited by John Beattie and John Middleton. New York: Routledge.

Emnoff, Ron. 2002. Recollecting from the Past: Musical Practice and Spirit Possession on the East Coast of Madagascar. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Friedson, Steven M. 1996. Dancing Prophets: Musical Experience in Tumbuka Healing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gelfand, Michael. 1964. Witchdoctor: Traditional Medicine Man of Rhodesia. New York: Fredrick A. Praeger.

Hood, Mantle. 1964. Atumpan: the Talking Drums of Ghana [Motion Picture]. Los Angeles: Institute of Ethnomusicology, University of California, Los Angeles in cooperation with African Studies Center, UCLA and School of Music and Drama, Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana.

Kiehl, Scott. 1999. Akom: The Art of Possession. Seattle: Village Pulse (VPU 1009).

Nketia, J.H. Kwabena. 1957. “Possession Dances in African Societies.” Journal of the International Folk Music Council 9: 4-9.

Nketia, J.H. Kwabena. 1963. Drumming in Akan Communities of Ghana. Edinburgh, Thomas Nelson & Sons.

Rattray, R.S. 1927. Religion and Art in Ashanti. London: Oxford University Press.

________. 1923. Ashanti. New York: Negro Universities Press.

Twumasi, P.A. 1975. Medical Systems in Ghana: A Study in Medical Sociology. Accra-Tema: Ghana Publishing Corporation.

________. 1972. “Ashanti Traditional Medicine and its Relation to Present-Day Psychiatry.” Transition 41: 50-63.

top

Daaho drummers. 2004. Daaho, 6 July.

Gyasi, Immanuel. 2004. Penteng, 28 May.

Nketia, J.H. Kwabena. 2004. Accra-Tema, 15 July.

Krobo drummers. 2004. Krobo, 30 May.

Obeng, Gyasi. 2004. Penteng, 28 May.

Obeng, Gyasi. 2004. Penteng, 4 June.

Obeng, Gyasi. 2004. Penteng, 6 June.

Obeng, Gyasi. 2004. Penteng, 7 June.

Obeng, Gyasi. 2005. (E-mail communication). 6 October.

Penteng drummers. 2004. Penteng, 28 May.

Sesease drummers. 2004. Sesease, 24 May.