Review | "Keep On Keepin' On," directed by Alan Hicks

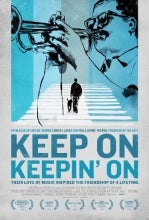

Keep On Keepin' On. Directed by Alan Hicks. 86 minutes. Radius-TWC, 2014.

Reviewed by Ben Doleac

Like too many great teachers, Clark Terry is nowhere near as widely known as his most successful students. Unlike such great jazz educators as Marshall Stearns and Gene Hall, however, Terry is a brilliant, prolific musician in his own right, which makes his relative obscurity outside jazz and music industry circles doubly unfortunate. Alan Hicks’ Keep On Keepin’ On, which opens at the Landmark and Arclight theaters in Los Angeles tonight, seeks to rectify this problem, paying overdue tribute to a man who has mentored dozens of great players. Shot over the course of five years, the film includes some background history and a handful of testimonials from noted former students, but focuses primarily on the contemporary relationship between Terry and one of his most dedicated pupils, a blind pianist named Justin Kauflin. Skipping as it does between the past and the present, Keep on Keepin’ On is remarkably fluid and engrossing, and positively astonishing as a first-time effort from director Hicks.

The film opens at the 2010 Grammy Awards ceremony, where Terry is presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award. Though far from a household name, Terry is hugely esteemed within the music industry, and given his extraordinary energy (the film’s press kit mentions that for decades Terry has only slept about three hours a night), optimism, humor and wisdom, all of which are on display in the film’s past and present interviews, it’s easy to see why. Hailed as one of the greatest trumpeters in jazz history by no less of a titan than Dizzy Gillespie, Terry has made nearly a thousand recordings over a seventy year career that includes stints in the orchestras of Count Basie, Duke Ellington and onetime pupil Quincy Jones. In 1960, Terry became the first black staff musician at NBC, and for ten years he served as a member of the Tonight Show band. Over the past three decades, however, Terry’s greatest passion has been for teaching, with such luminaries as Jones, Miles Davis and Dianne Reeves numbering among his former students.

Just shy of his 90th birthday and struggling with advanced diabetes at the start of filming, Terry is beset by failing health throughout Keep On Keepin’ On. As Kauflin explained at a press conference before the film’s Wednesday premiere, however, teaching seems to give Terry the strength to face even his gravest health struggles: “The act of teaching is something that really has empowered him and given him new life…he loves it so much that it really has been something that’s invigorated him.” Kauflin’s entrance into Terry’s life seems to have a similarly revitalizing effect; the young pianist shares Terry’s stubborn optimism and good humor, along with a dedication to perfecting his craft that matches his teacher’s seemingly inexhaustible reserves of tunes, tips, and tales. In late night hangs at Terry’s home and at a local hospital where Terry is receiving treatment, Kauflin transforms Terry’s snatches of hummed melody into fully harmonized songs, almost as if by magic. It is unfortunate that humming and snippets of often-vague wisdom are all the viewer really glimpses of Terry’s teaching methods; at times one senses he and Kauflin are communicating in some shared dialect unknown to all but Terry’s most advanced students. A few glimpses of Terry teaching a beginner might go some way towards demystifying his methods, which are praised throughout the film by famous former students and jazz heavyweights like Wynton Marsalis, but Hicks apparently did not have any such footage available. More important to him, and most likely for wider audiences, is the tightening bond between Kauflin and Terry, and that it remains somewhat mystical to the viewer only enhances the story’s broader appeal.

A born storyteller with a Spielbergian appetite for sentiment, Hicks is never afraid to pull at the heartstrings. Dubbing Terry’s taped words of wisdom to Justin onto the soundtrack, Hicks veers just this side of corny, but a scene where Terry’s wife consoles him just before a major operation is genuinely wrenching, and Kauflin’s bedside chats with Terry brim with jokes and affection. Even the most intimate scenes feel utterly natural, for which Hicks credits the already close ties between cast and crew. Born in Australia, Hicks first met Terry as an aspiring jazz drummer at William Paterson University. There he and Kauflin received an intensive and far-reaching crash course in jazz history and technique from Terry, who led them in a small combo. After graduating, Hicks, who had no prior background in film, sought to make a fairly straightforward biographical film on Terry, combining footage of his own studies with the trumpeter with reminiscences from former students and historical footage of Terry’s performances. After a year of filming Terry at his home in Arkansas and a lack of interest from potential producers, Hicks and cinematographer Adam Hart decided to focus on the relationship between Terry and Kauflin, who always seemed to be visiting for lessons. The duo finally found a producer when they decided to shop their project around to anybody within earshot on the streets of the Sundance Film Festival, but their most serendipitous encounter came less than a year before filming was completed. Trumpeter, arranger and producer Quincy Jones showed up to Terry’s house to record a collaboration between Terry and the rapper Snoop Dogg, but at the last minute Snoop failed to show due to a sprained ankle. Jones took the opportunity to reconnect with his ailing mentor, and their exchanges in the film are rife with the in-jokes and easy rapport that only comes with decades of friendship. At Terry’s urging, the fleet-fingered Kauflin showed off the results of his apprenticeship in an impromptu performance for Jones, and within months the film had a second producer, the necessary funding to see the project to completion, and the attention of Hollywood. Even sweeter, Kauflin had a record contract and an opportunity to tour the world with Jones’ orchestra.

Above: Quincy Jones and Justin Kauflin at the Four Seasons Los Angeles, September 17, 2014

Unsurprisingly, Kauflin, Hicks and producer Paula Dupré Pesmen came off as guests in King Quincy’s court during a press junket at the Los Angeles Four Seasons hotel on Wednesday, the afternoon before the film’s premiere. Journalists were treated to a roundtable with Jones and Kauflin and another with Hicks and Pesmen, though it was the old pro and master networker Jones who dominated the proceedings. At 81, Jones has been on the PR hustle for so long that he no longer feels compelled to play by anyone’s rules but his own. Commenting after one of Jones’ off-the-cuff exegeses, Kauflin clearly enjoyed Jones’ wide-ranging enthusiasm even if it left some of the reporters flummoxed: “Quincy, when he’s talking about the spirit of music and jazz and stuff, he’s all-embracing. Whenever he gets on – you can see just in him talking, he just embraces everything.” In the last ten minutes of the roundtable alone, Jones explained how jazz would never have existed without the French, touched on the role of television and the Voice of America radio broadcasts in breaking down cultural barriers during the Cold War, and advocated for the creation of a national ministry of culture. If at times he betrayed his status as entertainment industry royalty, Jones also embodied Terry’s philosophy of sharing one’s own accumulated knowledge with the world, having long since transformed into a mentor himself like so many of Terry’s former pupils. I’m sure there’s another movie in that somewhere. In the meantime, however, Keep On Keepin’ On pays Terry’s wisdom forward with equal aplomb.