Colonial Celts and Christmas Carols: Cornish Music and Identity in South Australia

Cornwall, at the far south west of the United Kingdom, is simultaneously a county of England, a royal Duchy, and Celtic nation, and as such its culture and heritage bears witness to a long history of conflicting social, economic and cultural pressures. Cornwall’s musical traditions have often been overshadowed by other aspects of its heritage as well as by the outputs of its Celtic cousins; however, both Cornwall’s contemporary and historical musical heritage is rich and varied, with a range of genres and styles.

Above: Map showing Cornwall, UK courtesy of Nilfanion.

Cornish carols are one such genre; a social and musical tradition performed at Christmas, as opposed to May or Easter carolling traditions. The local representation of a non-conformist religious choral practice that was widespread across the United Kingdom, the corpus known today as Cornish carols is largely the result of an upsurge in carol composition following the visits of John Wesley (1703-1791) and the subsequent growth of the Methodism. Surviving caroling traditions in Cornwall, such as those in Padstow, reflect elements of practices described in early nineteenth century accounts of caroling practices in Cornwall. These accounts describe groups of musicians touring their particular town, village or parish throughout the night singing carols to the local residents at their houses (Gilbert 1822; Sandys 1833). The musicians were also usually rewarded with some money or food and drink.

Above: Carolers outside the Golden Lion pub in Padstow, December 2010 (photo: Elizabeth Neale).

Above: The Padstow carolers performing "Zadoc" (Recorded by Elizabeth Neale, 2011).

Sounding Out: The Cornish Association

Cornish carols were spread across the world during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries through the migration of Cornish miners to the British colonies and other territories (Payton 2005). Their presence in South Australia during the 1890s is of note since the carols were explicitly tied to perhaps the most fervent contemporary expressions of Cornish identity. The discovery of copper at Kapunda, Gawler and the northern Yorke Peninsula in the mid-nineteenth century resulted in thousands of Cornish miners voluntarily traveling to the colony with the aid of government-assisted passages. In particular, the towns of Moonta, Wallaroo and Kadina (the Copper Triangle) became known as Australia’s “Little Cornwall,” and continue to celebrate Cornish heritage. The prominent historian of the Cornish in Australia, Professor Philip Payton, considers that the nineteenth-century Cornish communities in the Copper Triangle not only unconsciously retained Cornish culture in their continuation of existing cultural habits, but also that “individuals and organizations deliberately replicated former behaviour or adopted ‘Cornish’ rhetoric as a means of asserting community or institutional identity in their new land” (Payton 2007:57).

Adelaide was evidently also a strong locus of Cornish identity, since it was there that the Cornish Association of South Australia (CASA) was formed in 1890. The project of a group of influential Cornishmen, the CASA’s aims were not only to facilitate social interaction and to aid new migrants in South Australia, but also to promote Cornish culture and customs. Complex narratives of race and identity immediately emerged within the CASA’s rhetoric; during the inaugural banquet, John Langdon Bonython (vice-president of the CASA) made a speech in which he overtly positioned the Cornish as the descendants of the pre-Roman inhabitants of the United Kingdom, stating that it was “the stock of these hardy Celts which were now building up this Greater Britain of the South” (The Advertiser 22/2/1890:5). However, he was also at pains to maintain their British credentials and unswerving allegiance to the empire:

Their monuments were in every continent, and no people had done more to build up the British Empire than the people of Cornwall. (Loud cheers) They talked about hands across the sea uniting the various portions of the British Empire, and making federation possible, but whose hands were they but the hands of Cornishmen, who in their pride of race never forgot that they were citizens of the British Empire. (The Advertiser 22/2/1890:5).

The foregrounding of race in these dialogues reflects the contemporary social and scientific preoccupation with classification. The term race was often interchangeable with “species,” and in the context of human civilizations, connoted language and culture alongside physical and mental characteristics. As such, positioning the Cornish as a Celtic race and therefore separate from the Anglo-Saxon English was a powerful assertion of distinct biological and cultural identity.

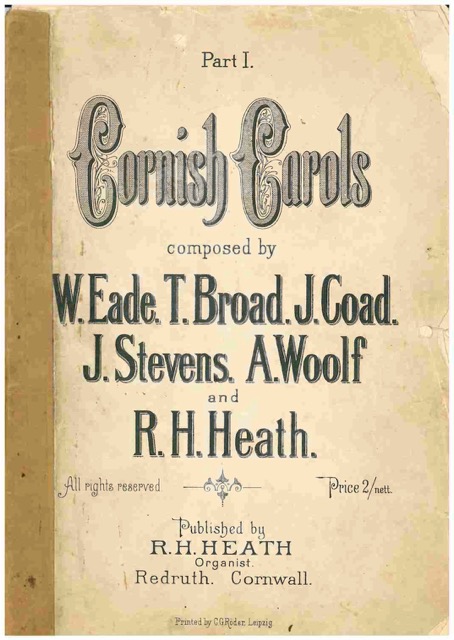

These dialogues of race and identity were reiterated during the CASA’s promotion of Cornish carols. The Cornish Musical Society (CMS) was formed later in the same year with the express purpose of practicing specifically Cornish carols to be sung at Christmas under the auspices of the CASA. The group gave their first concert in 1890, using as their source material a collection that was published by musician, collector and teacher Robert Hainsworth Heath in Cornwall in September 1889.

Above: Frontispiece of Robert Hainsworth Heath’s Cornish Carols, Part 1, published in 1889 (photo: Elizabeth Neale, author’s copy).

The first of two collections of Cornish carols, Heath included pieces that he had collected from other local composers, as shown on the front cover, and others that he had composed himself. Well-publicized both before and after, the initial concert was a success and it was repeated and expanded the following year. At this gathering, Bonython stated that:

It was a long retrospect to look through nineteen centuries back to the time when the first Christmas carol was heard on the plains of Bethlehem. But Cornish people should never forget that a hundred years had not elapsed before carols celebrating the Nativity were being sung in Cornwall and that they had been sung there forever since. Passed down from generation to generation, the strains of these carols linked the present with the past and united the Cornish of today with the Cornish of the first century. It was no wonder that the people of Cornwall were carol singers, and that wherever they might be found they still sang at Christmastide the sweet songs of the old home. (The Advertiser 28/12/1891:6)

In spite of the rhetoric conveyed by admirers of the carol tradition, a further examination of the genre, music and texts utilized by the Cornish Musical Society further complicates the conception of Cornish identity promoted by the Cornish Association in two primary ways that highlight the musical collision between a Cornish and British imperial identity. First, while the collection includes a number of texts not yet found in extant collections of hymns and carols, and are therefore likely to have been composed by Cornish musicians, it concurrently, also includes texts such as “Joy To The World,” and “While Shepherds” from English and Scottish hymn writers such as Isaac Watts, John Cawood and James Montgomery. These are not of Cornish origin and would have been well known across the United Kingdom. Second, the style of the musical materials cannot be said to be unique to Cornwall. Cornish carols generally are written for four parts (sometimes sharing three parts between SATB) and are usually unaccompanied, although historical accounts often describe he presence of instrumentalists within caroling parties (Shaw 1967:102). While the carols may employ a variety of texts, they characteristically begin in unison, and as the stanza progresses, develop a fugal section before returning to complete the stanza in unison. As such they are rather analogous within the genre of Protestant hymn fuging tunes, popular in both England and America in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Temperley 1981). There is therefore a clear disjuncture between the provenance of the musical materials utilized to support Cornish identity, and the cultural and biological heritage claimed by the CASA.

Reconstructing Music, Contesting Identity

The vision of Cornish identity disseminated by the CASA thus included intertwining and colliding notions of Celtic, English, British and imperial identity; however, the musical materials that were used to support an ancient Cornish heritage were not congruent with the history claimed by the CASA. This is not to suggest that the genre of Cornish carols is academically illegitimate, or that the CASA were deliberately misleading; rather, the intention is to recognise the constituent materials of the tradition in conjunction with the rhetoric put forward by the CASA in order to gain a deeper insight into the narratives at play. Indeed, the CASA’s initial promotion of Cornish carols appears to have bolstered the tradition significantly, considering the genre’s subsequent upsurge in performance and the further publication of other collections of Cornish carols within South Australia. The performance of Cornish carols became an established part of the CASA’s activities in the following decades. The tradition not only musically evoked a distinct historic identity and culture, but also was active in the present, socially bonding Cornish communities in the South Australia and conceptually bonding the Cornish across the diaspora.

The CASA’s efforts reflect the contemporary European political, sociological and compositional trends towards the use of folk or traditional culture in the project of nationalism and the process of nation-building (White and Murphy 2001; Bohlman and Radano 2000). In tandem, as scholars have increasingly critiqued, debated and deconstructed the concepts of race, the nation (Anderson 1983) and the socio-cultural apparatus of nationalism (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983), the door has opened for examining the construction and performance of identity within regions, among deterritorialised peoples and within other non-nation states. Further development of these debates among diaporic communities would broaden the academic perspective of migrant cultures, especially when their historical context is taken into account. As such, the Cornish caroling tradition, and the context and dialogues surrounding it, is significant not only for our understanding of historical Cornish diasporic identity in Australia, but also in ethnomusicological approaches to the music cultures and projects of historic migrant minorities.

Works Cited

Anderson, Benedict. 2006 (1983). Imagined Communities. London: Verso.

Bohlman, Philip V., and Ronald M. Radano, eds. 2000. Music and the Racial

Imagination. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Gilbert, Davies. 1822. Some ancient Christmas Carols, with the tunes to which they

were formerly sung in the West of England. London: John Nicholls and Son.

Heath, Robert Hainsworth. 1899. Cornish Carols, Parts 1 & 2. Leipzig: Robert

Hainsworth Heath.

Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Payton, Philip. 2007. Making Moonta: The Invention of Australia’s Little Cornwall.

Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

––––––. 2005. The Cornish Overseas: A History of Cornwall’s ‘Great Emigration’.

Fowey: Cornish Editions Limited.

Sandys, William. 1833. Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern. London: Richard

Beckly.

Shaw, Thomas. 1967. A History of Cornish Methodism. Truro: D. Bradford Barton

Ltd.

Temperley, Nicholas. “The Origins of the Fuging Tune” In Royal Musical Association

Research Chronicle 17:1-32.

The Advertiser (South Australia: 1889-1931). "Cornish Association, Inaugural

Banquet – An Enthusiastic Gathering" (writer unknown). 22/2/1890:5.

––––––. "Cornish Musical Society: Christmas Carols" (writer unknown), 28/12/1891:6

White, Harry, and Michael Murphy. 2001. Musical Constructions of Nationalism:

Essays on the History and Ideology of European Music Culture 1800-1945.

Cork: Cork University Press.

Bio

Elizabeth is a second year PhD candidate co-supervised at Cardiff University and the Institute of Cornish Studies at the University of Exeter. She received her BA in music and English literature and MA in ethnomusicology from Cardiff University, and her project is supported through the South West and Wales Doctoral Training Partnership.