Book Review: "People Get Ready: The Future of Jazz Is Now!"

People Get Ready: The Future of Jazz Is Now! Ajay Heble and Rob Wallace, eds. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

“Thus it is in our own roles as teachers, musicians, and scholars that we come to this project with passion, energy, and love. The creation of this book has been a collaboration called and responded to one another in both music and in writing, as we have developed this volume.”

-Heble and Wallace, introduction to People Get Ready.

As the quote above shows, this book—the first in Duke University Press’ Improvisation, Community and Social Practice (ICASP) series—takes its relationship to the practice of improvisation seriously. It is one of the recent manifestations of the ICASP research project, an interdisciplinary program housed at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada that connects researchers around the world working on understanding improvised music-making as a model for social change. Last summer, I had the tremendous privilege of participating in their biennial Summer Institute, where I developed a direct appreciation for the cutting-edge thinking going on there.

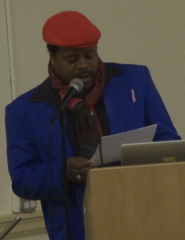

Co-Editor Rob Wallace presiding over an improvisation workshop at the 2012 Guelph Jazz Festival. That's me seated behind the trombone.

Reading People Get Ready, then, I couldn’t help but harken back to the vibe of my experience in Guelph last year, much of which is reflected in the pages of this collection. The book’s nonhierarchical structure, which puts the words of scholars, musicians, teachers, and critics next to each other with minimal editorial commentary, is certainly one of its hallmarks. Although this makes for some occasionally dissonant contrasts, especially in the first and third sections, what could be dismissed as incoherence could also be seen as one of the book’s strengths: this strategy leaves the forging of meaningful connections up to the reader.

After Heble and Wallace’s introduction, which stakes the positive future of jazz on the lineage of improvised music-making that coalesced around the “New Thing” in the 1970s, the essays are divided into three parts. The first, “Beyond Categories: Histories and Mysteries,” includes five essays on various marginalized histories that inform the music’s avant-garde present: Aldon Lynn Nielsen on Cecil Taylor’s poetry and the sounds of the black voice, John Szwed on Duke Ellington’s relationship to the jazz avant-garde, Julie Dawn Smith and Ellen Waterman with two close readings of a 2002 performance by George Lewis’s “Dream Team,” Eric Porter on jazz singer, educator and activist Jeanne Lee’s experimentations with vocality, and Rob Wallace on the intertwined histories of free jazz and punk rock.

The second section is probably the most “put-together” of the three, because it derives its core from a panel of conference papers given at the 2007 Guelph Jazz Festival Colloquium. The five chapters in this section, “Crisis in New Music? Vanishing Venues and the Future of Experimentalism,” discuss the pressing issue of disappearing creative music spaces, sparked by Marc Ribot’s opening piece which protests the 2007 closing of Tonic, an important haven for improvised music in New York City. The following chapters include Tamar Barzel’s thoughtful meditation on how new spaces for improvisation might emerge, John Brackett’s forceful rebuttal of Ribot’s call for state subsidies, Scott Thomson’s counterpoint about experimental music spaces in Toronto, and Alan Stanbridge’s thorough consideration of government arts policy’s structural failure to support small-scale creative experimentalism.

Because of the focus on practical issues that surround improvised music in the 21st century, this section comes the closest to the “now” of the book’s title. This also points to one of the book’s biggest limitations: the “now” is actually 2007, not 2013. Of course, this isn’t the editors’ fault—such is the nature of academic publishing—but it certainly highlights the problems inherent to the “academic book” form. Much of the discussion remains highly pertinent, such as the increasing sophistication with which neoliberal market ideologies crowd out the progressive ethos imbedded in the communities that make this music; however, thanks to the rapidity of technological change, parts of this section are already out of date. For example, John Brackett’s call for creative improvisers to make their music available on the internet as a viable alternative revenue stream certainly rings hollow in this age of Spotify and Pandora—as Radiohead star Thom Yorke’s recent actions suggest.

In fact, the book’s third section—a collection of candid photography by Thomas King—captures the feel of the Guelph scene even better than the essays do. My favorite is a backstage shot of flutist Nicole Mitchell (who is featured later in the book as a panelist on the AACM) smiling mischievously as trumpeter Rob Mazurek warms up his trumpet to her left. The photo reflects the lively joyful quality that permeates the annual festival and colloquium.

The fourth and final section of the book, entitled “Get Ready: Jazz Futures,” brings together four meditations on where this music and this social movement seem to be going. The first, Greg Tate’s “Black Jazz in the Digital Age,” beautifully encapsulates the paradoxes that jazz faces as it transitions into the 21st century. While noting the struggles that the music faces today, Tate (pictured, right) and the rest of the authors in this section manage to strike an optimistic tone. Most do so by offering more questions than answers, modeling the practice of playful seriousness that is central to the tradition of jazz-tinged musical improvisation. The second chapter is a conversation between Vijay Iyer and DJ Spooky (Paul D. Miller) on the nature of improvisation, community, and the digital. Iyer focuses on the potentials and possibilities of live performance, while Miller positions remixing and versions as central tools for improvised music-making today. Another conversation follows, featuring many core members of the AACM reflecting on the organization’s 40th anniversary which took place in 2005. This chapter is perhaps a microcosm of the whole book: a diverse array of knowledgeable improvisers riffing on the musical practice and community that has inspired them.

The fourth and final section of the book, entitled “Get Ready: Jazz Futures,” brings together four meditations on where this music and this social movement seem to be going. The first, Greg Tate’s “Black Jazz in the Digital Age,” beautifully encapsulates the paradoxes that jazz faces as it transitions into the 21st century. While noting the struggles that the music faces today, Tate (pictured, right) and the rest of the authors in this section manage to strike an optimistic tone. Most do so by offering more questions than answers, modeling the practice of playful seriousness that is central to the tradition of jazz-tinged musical improvisation. The second chapter is a conversation between Vijay Iyer and DJ Spooky (Paul D. Miller) on the nature of improvisation, community, and the digital. Iyer focuses on the potentials and possibilities of live performance, while Miller positions remixing and versions as central tools for improvised music-making today. Another conversation follows, featuring many core members of the AACM reflecting on the organization’s 40th anniversary which took place in 2005. This chapter is perhaps a microcosm of the whole book: a diverse array of knowledgeable improvisers riffing on the musical practice and community that has inspired them.

The final essay, by Tracy McMullen, brings the endeavor firmly back into the academic sphere, using philosophical discourses from Derrida, Buddhism, and jazz improvisation to critique the “liberal-humanist, post-Englightenment tradition that privileges subject-object divisions, the coherence and defense of identity, and the related objectification of time into the past, present, and future.” (265) The story she offers of Herbie Hancock’s conversion to Buddhism—by way of an inspired improvised solo by bassist Buster Williams, and not by any verbal or linguistic proselytizing—exemplifies how music will be central to how we communicate new understandings of time and philosophy in the 21st century.

This book, limited as it is to the medium of visual and linguistic signifiers, nonetheless articulates the sense of immense possibility—what Tate brilliantly describes as the “tachyon-beamed, future-sent black cultural revolution in sound” (217)—that is so palpable in other ICASP events and programs. This willingness to experiment, to listen closely, deeply, and broadly, and to engage in collaborative conversations through music, speech, and writing, reflects a practice that all musical scholars—especially ethnomusicologists—would be wise to emulate.

--

Alex W. Rodriguez is the Managing Editor for the Ethnomusicology Review Sounding Board. He is also a writer, trombonist, and PhD student in ethnomusicology at UCLA.