Dispatch from Northern Jalisco – Return to Huilotita & the Ethics of Documentation

In June of 1944, U.S. researcher Henrietta Yurchenco and a team of Mexican government workers set out on a multi-day journey from the old mining town of Bolaños in northern Jalisco. The team, aided by donkeys carrying supplies and audio recording equipment, were on a mission—funded by the U.S. Library of Congress—to find and document “survivals” of prehispanic music and ritual amongst the people then known as the Huichols, now better known as Wixáritari (see my previous post for an explanation of the two terms). It was a grueling, dusty trek over many massive mountains and precipitous peñascos. Eventually, the team arrived in Huilotita, a small rancho (village) with thatch-roofed houses and elevated bamboo-like granaries. Yurchenco made many recordings, a companion took photographs of the event, and then the visitors loaded up the donkeys, said goodbye, and left Huilotita for good.

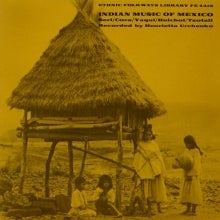

Yurchenco deposited her Huilotita recordings, among others, in the Library of Congress where the originals still reside [AFS 7612-7634], now part of the American Folklife Center. A couple of the pieces were released commercially by Moses Asch on the Folkways record label in 1952 as “Indian Music of Mexico,” now available through Smithsonian Folkways. Though I did have the pleasure of speaking with Henrietta over the phone before she died, we didn’t get to the details of this experience. Considering the era, though, it is doubtful that the people of Huilotita were aware that their sounds would be sold abroad. Certainly, no royalties, however small, ever made their way back to the remote mountains of Jalisco.

In October of 2012, I made my own journey to Huilotita to repatriate copies of Yurchenco’s recordings and photos taken over 68 years ago. I was accompanied by Ukeme Oscar Bautista, the founder and director of PuebloIndigena.com. Although Ukeme lives in the region, he had only heard of Huilotita, and few people knew how to get there. Huilotita now is far easier to reach than in the days of Yurchenco’s visit, but it’s still fairly remote. A road was constructed seven years ago that connected it to the main highway between Bolaños and Tuxpan–remote outposts in their own right—but by the time we actually piloted Ukeme’s Jeep down that road, it had been mostly overtaken by weeds and eventually became impassable. We walked the rest of the way—only about 10 minutes—and conspicuously sauntered into Huilotita where they were beginning preparations for Tatei Neixa, a first-fruits ritual that also initiates children into Wixárika society.

After making some small talk and being fed frijoles and homemade tortillas, we explained our surprise visit. The local representative of the traditional council of elders was pleased but surprised to hear about Yurchenco’s work. In fact, somewhat to our dismay, no one in the village recognized the people in the photos. I supposed we were romantically hoping for some sort of tearful stories about grandparents whose visages had not been seen in years. Instead, we found only one elder (in a completely different village) who nonchalantly identified his grandmother and a few others in a group photo along with Yurchenco.

The repatriation of the materials was documented on PuebloIndigena.com, where I can be seen trekking to Huilotita and looking on as residents peruse Yurchenco's photos. The local authority in Huilotita also graciously allowed me to record the Tatei Neixa ceremony and take photos, documenting the music in ceremonial context rather than performed in snippets for the sake of Yurchenco’s recorder.

Early on, I decided on the title “Return to Huilotita” for this blog entry. But why did that title even come to mind? Who was actually returning? The materials were returning in some sense, but subconsciously I feel I was channeling a sort of “us” and “them” mindset, imagining Yurchenco as my own sort of ancestor in the same way I imagined or hoped for a genealogical continuity of Huilotitans.

There were three politics of documentation at play in this multigenerational and intercultural encounter: Yurchenco’s, Ukeme’s, and mine. Ukeme, for example, documented and published information about the event online without informing me or the residents of Huilotita in advance, though he is a local in some sense and I doubt it would have angered anyone. Similarly, though Yurchenco presumably asked permission to record upon arrival, it was probably not clear that the recordings would be sold commercially in the future. Both documented experiences as means of furthering their careers and communicating across various boundaries. In some sense, ethnographic work leading to a doctoral dissertation performs a similar type of work but ideally is done with the utmost concern for ethical conduct. Indeed, legitimate and ethical ethnography is often made infuriatingly difficult as a result of the less-official sorts of documentation that are increasingly common in today’s digital world. In fact, I was recently denied permission to conduct research in another Wixárika community as a result of a prior incident with foreigners attempting to make a documentary without permission from Wixárika authorities. The situation was still “hot” and, rather than hear out my intentions, elders simply cut off outsider access altogether.

It would of course be ideal if we could simply show up and say “mind if I take some photos.” It would be much easier to simply take photos and video without asking permission at all, as any local would do even in the most intimate of settings. Perhaps there is no mechanism that ultimately guarantees ethical interactions and proper use of documentary materials. Despite the consent forms that IRBs would like us to present to every single person we engage in idle chit chat, all we really have is person-to-person and person-to-people commitments. This, unfortunately, is too easily forgotten when the focus in on “culture” as a monolithic collectivity or on people merely as carriers of some mythical/mystical “ancient” practices. It would probably be ideal to focus on nurturing interpersonal interactions and relationships long after the official research has ended. But how many researchers who were made famous working in one area continue to pursue friendships and commitments in those areas years after the book is written? Who could afford to pursue such long distance contacts on an adjunct professor’s salary? Nevertheless, ongoing contact of that sort might better assure proper use of documentary materials, and even deepen ethnographic insights, but more importantly it might cultivate a more profound humanity.