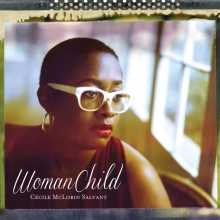

Enunciating Power and Ex…Plosive Time: Cécile McLorin Salvant’s “Woman Child” and Silence Undone

WomanChild, Mack Avenue MAC 1072, 2013. Personnel: Cécile McLorin Salvant, vocals, piano (track 10); Aaron Diehl, piano; Rodney Whitaker, double bass; Herlin Riley, drums; James Chirillo, guitar, banjo. Tracks: St. Louis Gal; I Didn't Know What Time It Was; Nobody; WomanChild; Le Front Caché Sur Tes Genoux; Prelude/There's a Lull in My Life; You Bring Out the Savage in Me; Baby, Have Pity on Me; John Henry; Jitterbug Waltz; What a Little Moonlight Can Do; Deep Dark Blue. Recorded at Avatar Studios, New York, NY. www.cecilemclorinsalvant.com

--

Of all the countless, captivating moments I have heard and re-heard in WomanChild, there are two that struck me right away—on my first listen to the album—and that continue to surprise me each time I hear them. I haven't been able to let these moments go—not for the three months prior to the album release when I carried around the album with me on my daily commute and not since. The repeated and recurring power of these musical moments inspired me to a particular, directed listening. I started searching the album for more, intently focused not only on what she performs (and doesn't perform), but also how and when she performs. Small but powerful moments like these—and the philosophy behind them—are at the heart of McLorin Salvant's artistry. Never ostentatious or frivolous, the art lies in spontaneous emergence and beautiful accumulation of small gestures, informed by empathetic collaboration, careful study and forethought, and masterful execution.

Propelled by her first-place finish in the 2010 Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, Cécile McLorin Salvant's refreshing perspective on jazz and African diasporic music is reaching increasingly wider audiences who are reacquainting themselves with musical and cultural history via her masterful performance of some of its overlooked moments, compositions, and people. Inasmuch as she facilitates this re-introduction, many among her audiences are meeting McLorin Salvant for the first time. A mix of admiration, astonishment, and intrigue surround this 23-year-old artist whose diverse cultural and musical backgrounds enrich WomanChild, making it a highly personal—but not necessarily autobiographical— album. But, beyond cordial introductions and incipient back-stories, McLorin Salvant's music communicates and promises so much more than just staking her rightful claim as an up-and-coming artistic force and intriguing persona on the global jazz scene.

WomanChild begins with the other St. Louis Blues—"St. Louis Gal"—written by J. Russel Robinson and popularized by Bessie Smith. From the very first note, listeners are immediately clued in to McLorin Salvant's take on the African American popular music and jazz canons. Unlike the listless main character in W.C. Handy's much more widely known and recorded blues, Robinson's character is empowered by her lost love, even promising to "man-handle" the St. Louis Gal who stole him. Evoking a period contemporaneous with Handy's hit but from a more critical vantage point, McLorin Salvant shows us another important, but overlooked, perspective of jazz history and African American musical culture via a forgotten composition and character. She effectively embodies that character's dual state of insistent longing and self-actuating power through a range of vocal techniques—variations in tone, vibrato, and diction—supported by instrumental accompanists who show equal flexibility in performing this piece in a period style.

"I Didn't Know What Time It Was" introduces one of the album's binding creative concepts and most important motives—the manipulation of time. Over syncopated comping that ticks along like clockwork, McLorin Salvant doesn't just sing the lyrics to this well-known and widely recorded standard. She performs the song's meaning, de-constructing its steady tempo by slowing down her vocal phrases with rubato and shifting them across barlines—out of sync with the measured accompaniment and more canonical renditions of the song. Bassist Rodney Whitaker and pianist Aaron Diehl provide adept improvisations that mix dexterous, chromatic lines with soulful motives and licks before re-establishing the clockwork setting for McLorin Salvant, who revises her melody with still more changes in register, phrasing, pitch selection, and tone. She exits the tune on her own—while the band…and the time…keep going. On "Nobody," the ensemble once again attaches a well-crafted period vibe to a tune popularized by the vocalist Bert Williams in the 1930s. Treating listeners to another largely forgotten piece of African American popular music, McLorin Salvant once again inhabits the character through her voice, eliciting both empathy and pity for this overlooked soul. Behind the cute, kitsch performance lies a message similar to "St. Louis Gal"—self-advocacy amid alienation and loss. After recounting numerous episodes when friends, community, and society at large denied her existence and worth through inaction and disinterest, the tune's character resolves to act and advocate for herself first. Insisting that at "no time" will she look to help those who passed her over before herself, McLorin Salvant once again exits early, leaving the band to tie up the song's final cadences as an instrumental piece and without the newly re-forgotten "Nobody" character.

The centerpiece of the album—its title track—features a powerful poetic message written and set to music by McLorin Salvant. What may first present as aggression in the band's approach is more aptly described as an entreating, political insistence reminiscent of 1960s African American cultural movements in both jazz and poetry. Over a repetitious and repeated bass ostinato, the band hammers through this composition, with McLorin Salvant's percussive consonants (plosive and otherwise) firmly establishing her as a full participant in the band's polyrhythmic milieu. The track's power comes largely from its dynamic, re-iterative emphasis on the lyrics set in sharp relief to the band's accompaniment. With subtle variations in each statement of the melody, McLorin Salvant and the band repeat themselves to make sure we're listening to her poetry and its message. On the word "undone" McLorin Salvant delves deep into her lower register, firmly and confidently performing a two-note motive—in the extreme low range of pitches she sings on the entire album—that is immediately replayed by Diehl several times, who then uses it as a launching pad for his improvisation. Diehl in particular benefits from his collaboration with McLorin Salvant, performing some of the best recorded music of his career on an inspired, heavily punctuated, and richly harmonized solo over her composition. Wide-ranging in his ideas and coverage of the piano keyboard, Diehl rises to the moment contributing an emotional performance that imbues his customarily virtuosic playing with added energy and drive. Because they've featured this "undone" motive so prominently, listeners will notice its every appearance in the track—in other lyrics and from other instruments—drawing connections, recalling early instances, noticing subtle variations, all the time listening more deeply and more critically. And it's no irony or trite figure of speech that the WomanChild comes undone "when her time has come." Who this WomanChild is and what becoming "undone" means remain unanswered questions as the track concludes, but through the band's insistent repetition of the theme—varied slightly in lyrics, pitches, and instrument in each iteration—we come away understanding the importance of working out the answers.

Cécile McLorin Salvant and Aaron Diehl. Photograph by Matthew Lomanno.

As if to allow us time to reconsider what we just heard, the following track opens with the only instrumental passage of the album. In "Prelude," Diehl hints at what's to come but never plays out enough of the standard's melody to give it away entirely. Here the band provides McLorin Salvant ample space for consideration—she enters "There's a Lull in My Life" on and at her own time. Engaged by Diehl's melodic suggestions, McLorin Salvant's delayed entrance gratifies the listener in its long-awaited arrival but even more so in its sheer and supple elegance. And once she joins the band, McLorin Salvant proceeds patiently, elongating her phrases with rubato over the barline, lingering with and reveling in the melody's text just a bit...longer. (Notice the difference between the soft final consonants of the A melody—"a lull in my life"—and the harder, more percussive consonants of the B melody—when "the clock stops tic...king." Again, artistry in the smallest gesture!) It may seem like mere semantics or needless minutia, but listening to McLorin Salvant's consonants is a revelatory experience: she ends words and phrases with exacting and unique precision, occasionally eschewing convention and singing the sound of the consonant as opposed to elongating the vowel through the word and hastily capping it off. By interpreting a song's lyrics in such a personal way, McLorin Salvant makes the words her own, inhabiting a lyric not just through its characters, its message, and the sound of her voice but also in the way in which—and the time when—she pronounces each and every syllable.

Many of these nuances could be lost among U.S. audiences on the following track, McLorin Salvant's setting of "Le Front Caché Sur Tes Genoux" (The Face Hidden on Your Knees), a poem by Haitian writer Ida Faubert. Both McLorin Salvant and Faubert share strong connections as post-colonial female artists in the African Diaspora; and the themes McLorin Salvant has already set out in the album are echoed in Faubert's text (performed in the original French). Enveloped by the darkness of past memories, the poem's character laments her inability to acknowledge and accept the tenderness of her love's advances—destined to continue reliving her pain ("Je revivais l'heure lointaine," I was reliving that long hour). Despite any possible language barriers, listeners will still hear McLorin Salvant floating over her accompanying ensemble with finely crafted ornamentations on this waltz. Diehl's playing is once again noteworthy for his inventive improvisation and rich reharmonization of McLorin Salvant's melody. In a way "There's a Lull" and "Le Front" serve as sonic palette cleansers between two of the album's most powerful and evocative tracks.

As a musical and ideological complement to "WomanChild," "You Bring Out the Savage in Me" serves as another anchor for McLorin Salvant's artistic and socio-cultural platforms on the recording. Her choice to resurrect this all-too-conveniently forgotten song, popularized by the trumpeter and vocalist Valaida Snow in the 1930s, will doubtless raise eyebrows and perplex audiences unfamiliar with or unwilling to acknowledge this moment in jazz history. The song comes from the period when jazz musicians—mostly African American and Afro-diasporic—performed "jungle music," jazz that capitalized on and commodified racist, exoticist stereotypes of black and African music as inherently primal, unsophisticated, and sexualized. A form of minstrelsy updated for the 20th century and the jazz age, "jungle music" was a commercially popular fad that afforded African Americans—like Valaida Snow and Duke Ellington—the detestable quandary of undercutting their personal self-worth for economic subsistence and performance opportunities. As earlier performers had done with minstrelsy, Snow, Ellington, and countless others turned this racist fad on its head, confronting audiences with the stereotypes' absurdity and moral decrepitude through ironic and critical performance of the music. This is precisely from where McLorin Salvant picks up, with a head-on confrontation of the song's unabashed racism using a combination of humor, satire, and derision that mocks and undermines the song and the fad that produced it, but not without entertaining her audience along the way. McLorin Salvant's impeccable diction and deliberate exactitude with the lyric steep her performance with incisive irony, in which her total vocal control and perfectly enunciated lyric directly engage the audience so that they cannot possibly miss, mistake, or misunderstand what she's saying. (These consonants are not the same as the warm, round ones in "There's a Lull": edgy and powerful not just in their sound, but in their cutting, interpretative force against the lyrics. McLorin Salvant fights back with these consonants.) Through a range of vocal effects, she conveys humor and sadness, irony and outrage, adding subtle melodic variations in the melody in each of its repetitions. Of all the notes McLorin Salvant sings on the album, few are more perfectly performed in terms of classical vocal technique than those accompanying the text "you'll find out how wild I can be," more demanding because of their high register, but also the ultimate stroke of musical irony. The instrumental accompaniment supports her here as well: echoing the lyric, drummer Herlin Riley's resounding, polyrhythmic bombs on the tom drums and Diehl's pseudo-Afro-Latin-ish montuno riffs and reliance on open-fifth chords (neither major nor minor) perfectly evoke the ambiguity of quasi-Africanness at the center of the "jungle music" stereotypes. In the end, McLorin Salvant exits early again, but not before repeating "savage" a few more times…just to make sure we're listening.

After three-quarters of the album, certain themes are emerging: listeners will hear resonating sounds, messages, emotions, and motives from earlier tracks re-appearing and re-sounding in later songs (repeating with variation, that is). In "Baby, Have Pity on Me," we hear the main character once again abandoned, overlooked, and overcome with the blues because of the unrequited love she feels for the object of her desires. In the traditional folk song, "John Henry" McLorin Salvant renders a strong, assured celebration of an African American hero who champions workers' rights under the constant shadow of impending and inevitable demise, accompanied by a mysterious woman dressed in red, who resolves to stand in solidarity with and faithfulness to her departed beloved. In the wonderfully imbalanced and off-kilter "Jitterbug Waltz," McLorin Salvant accompanies herself on the piano, singing of love that yearns to linger with a willing, though weary, partner. Near the end of the track, she manipulates the song's time…slowing the tempo down and attempting to resist the clock's relentless ticking as the hour grows even later, in order to eek out just a few more shared moments for the waltzing lovers.

Recalling the earlier "Prelude," the ensemble begins "What a Little Moonlight Can Do" with a slightly eerie introduction that flows at a languid pace, hinting at but delaying the arrival of its melody and tempo. This ambiguous, listless phasing-in-and-out of tempo that they perform first never really goes away: the impeccably solid swing that finally settles in subsequently disappears several times during the track, giving the listener the impression that the band starts and stops the song itself several times, always with variation. With each repetition, McLorin Salvant performs the lyric with complete mastery, once again conveying the humor in the lyric amid the longing of its main character. In a stroke of artistic genius, she stutters, trips, and stumbles her way through the lyric "You only stutter cause your poor tongue / Just will not utter the words / 'I love you'." For the first time on the album, those edgy, well-supported, and enunciating consonants do not come. (For me, on my first listen to the album, this was the second of the two moments that struck me so deeply: McLorin Salvant's mumbly vocal trippings over the words "I love you" on this track and, in contrast, her perfect articulation of each and every syllable on "You Bring Out the Savage in Me." How, I wondered, could she pass over something so easily uttered several times, while confidently, clearly, and artfully pronouncing every syllable of lyrics laden not just with racial overtones, but with fundamental racism?)

As if to save her from this inarticulate mumbling, Diehl enters with an improvisation that rivals his earlier contribution on "WomanChild" in virtuosity, performing multiple lines simultaneously, overlaying the melody with highly intricate sequences and bebop lines…all at a breakneck speed. After an improvised exchange between Riley and Whitaker, the track's tempo/time disappears again and any trace of the song dissolves into a wash of sound, re-forming slowly and building back up to its frenetic pace for the last statement of the melody. When the moment comes for those words that McLorin Salvant has not been able to pronounce thus far, the ultimate repetition-with-variation occurs: any sense of time or tempo once again disappears as, with great contemplation and caress, she slowly and beseechingly delivers the words "I love you." The band re-enters at its previous, speedy tempo, pushing the song towards its inevitable end. Instead of carrying her to the end, though, this time the band drops out early, leaving McLorin Salvant to finish alone—confidently and with great strength—at the album's high point in both energy and pitch, nearly three octaves above those "undone" notes she sang in "WomanChild." She has ended the album quite literally on its highest note.

Except that the album is not over…there's one more, very unsettling track. It's no exaggeration to say that "Deep Dark Blue," an original composition and poem by McLorin Salvant, totally undermines the triumphant ending that she and her band have just executed in the previous track. With its haunting, obscure harmonies and angular intervals, the track festers with creepy uncertainty. Almost inexplicably, McLorin Salvant seems to contradict and disparage her earlier tracks—and the entire album—when she professes, "A fool did sing of sweet love / And everything that Spring could bring." When I heard this, I came across yet another fundamental question that still lingers: why would McLorin Salvant undo her own album? Appropriately, she responds and answers with yet another question:

"But what of days gone by? / And what of all the silence?"

After this the album does draw to a close—via a particularly curious set of harmonies—resolving the chord progression, but not the vocals, nor their message, nor the album itself. McLorin Salvant leaves us with "that feeling that has no name / Deep Dark Blue…Blue…Blue," with each of the repeated "blues" on three, different, ascending pitches. Stunned, imbalanced, and perplexed, we are left to wrestle with and parse out what she has just done—and undone—to us.

Obviously, if the masterful, climactic final cadences of "Moonlight" are not the album's last, there's something else McLorin Salvant wants us to hear and notice. So then one might ask, "What would the album imply if she ended with 'Moonlight'? What would we miss?" "Deep Dark Blue" may sound like quite the imperfect ending, but the questions she asks are not meant to neatly encapsulate her art, but rather to start a discussion with it. So the album's epilogue is actually the perfect unending. It continues and encourages contemplation across the last barline. If "Deep Dark Blue" is left out, what do we miss? The days gone by and all the silence—the moments and people that history has forgotten or overlooked. Those cast as "nobodies" and "savages." McLorin Salvant is not suggesting it's foolish to sing of Love and Spring, but rather that it's foolish to do so without remembering "that feeling that has no name…[the] deep dark blue(s)." In many ways, this is a common theme of the African American and Afro-diasporic histories that McLorin Salvant celebrates and re-energizes: art and love persisting amid great struggle and hardship. Each person finds her or his own path and, with WomanChild, McLorin Salvant has chosen a path of both celebration and solemnity. To confront past silences and caution against future ones. To mindfully recall the hardships and victories, sadnesses and joys, of those whose art she so deftly re-makes as her own.

Cécile McLorin Salvant, Paul Sikivie, and Rodney Green. Photograph by Matthew Lomanno.

Such individuality in jazz music is a tricky phenomenon: the line between ground-breaking genius and "the same-old-thing" teeters tenuously on a fulcrum that balances the familiar and the novel. Too much of the former and a performer can be cast as blasé, safe, and overly commercial; too much of the latter can bring charges of self-absorption, esotericism, and aloofness. As a result, young jazz musicians are placed in this double-bind wherein their success relies on acknowledging and successfully invoking their historical predecessors, while distancing themselves far enough from them that their own merits and goals can be appreciated. On WomanChild, McLorin Salvant has accomplished both with exceptional skill and artistry. But whether these accomplishments are accepted can often depend on critical reception and popular press. And in some of what others have written of her lie echoes of the very silences—and silencings—that she cautions against.

There is much talk of McLorin Salvant's cultural and musical background, such as her Haitian father, her study of baroque music, and her coming-of-age as a jazz musician in France. Unfortunately, some characterizations of her background focus on how different she is and these events are from "normal" musicians' upbringings. For example, she is depicted on the album's promotional page as "a mystery woman with the most unusual background of any of the [album's] participants." In describing her performances at a popular jazz club, Ben Ratliff once suggested in the New York Times that the audience realized it was watching "something unusual." While we shouldn't take such quotes completely out of context, the prevalence of objectifying, sexualized, or exoticist language—couched as it might be around ample and well deserved accolades—in reviews of her work should give us pause. For example, her singing has been described as "yodeling like Tarzan" (San Jose Mercury News) and "yodeling in ecstasy" (emusic.com). A reviewer in the Examiner preferred the language of bodily indulgence over that of artistic accomplishment to describe the end of "Moonlight": "She swallows each little syllable of ‘Ooooh’ like it’s her last meal, then hits the highest of highs with a final, orgasmic note.” (For an example of the latter type of language, see Andrea Carter's in-depth review on the Jazz Police website.) All of the occurrences and facts of McLorin Salvant's background have contributed to WomanChild, but the album and her success as an artist are not reducible to them. And while each artist brings individual experiences to bear on her or his performances, there is nothing endemic about McLorin Salvant's Haitian heritage (for example) that necessarily makes her art as successful and engaging as it is. Highlighting this as a constitutive element of her music and then describing it as "unusual" (rather than "unique," and "something unusual" rather than "someone unique") could be interpreted as attributing her artistic achievement to some inherent quality of her personal nature, which is potentially exacerbated when it is described through language that could have a negative connotation. And while I'm sure none of the writers quoted here intends any such connotation with their words, through her provocative manipulation of language on WomanChild, McLorin Salvant provides an instructive reminder to her audience—writers included—that we ought to exercise as much care, critical thought, and historical awareness in our language as she does in hers. By featuring "You Bring Out the Savage in Me" so prominently on the album, McLorin Salvant reminds us of the "jungle music" era, which was perpetuated in part through language and literature that dehumanized Afro-diasporic culture and individuals with an exoticism that quite literally confined female performers of the era to cages. The era may have changed, but the stakes are just as high.

On a related note, in the spirit of parsing critical words, I wish to suggest a counterargument to Ben Ratliff's comment in the same New York Times piece that McLorin Salvant has a penchant for mimicry that must be outgrown and squelched for her to achieve her artistic potential. Here lies a prime example of how critical words can direct (and misdirect) public perception of an artist. Can one at times hear traces of Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and Billie Holiday (among others) in McLorin Salvant's delivery? Absolutely. But why call it "mimicry" and not "mastery"? Quotation of standard repertoire, well-known improvisations, and signature "licks" is a time-honored way of demonstrating the very historical knowledge by which young musicians are judged. Given McLorin Salvant's artistic choice not to improvise via scat-singing, why not treat these incidental moments as improvisational invocations of personal influences and historical predecessors in that same tradition of quoting? Of exploring a full range of both fictional and actual characters through deftly executed vocal affect? Why "mimicry" and not "mastery"? Furthermore, considering McLorin Salvant's treatment of standard and historical repertoire throughout WomanChild—with many, varied moments of repetition enriched with those subtle changes—why not treat her approach to the sound of these historically important artists' voices the same way?

In his book Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity, Alexander Weheliye writes that, for Afro-diasporic artists whom history and politics have marginalized, such repetition of variation is a powerful form of critique and self-determination

"wherein the original/copy distinction vanishes and only the singular and sui generis becomings of the source remain in the clearing. This repetition of difference does not ask how 'the copy' departs from 'the source' but assumes that difference will indeed, be different in each of its incarnations."

Invoking W.E.B. Dubois's The Souls of Black Folk, Weheliye continues by adding that the addition of sound to text "exemplif[ies] the aesthetic complexity and cultural flexibility of a sonic (black) temporality [that] generates a genuinely 'new' modality, a different groove...." Like DuBois's work, McLorin Salvant's masterful manipulation of language, pitch, and sound in WomanChild,

"provide[s] written words with a sonorous surplus [and] structures [it] as a phono-graph…that attempts to make the souls of black folk sound and be heard, which is not so much a strict opposition between notated sounds and written words as an augmentation of words with sounds, of adding back into the mix what gets left out in the equation of language and speech with linguistic structures."

In other words, by referencing and varying the sound of some of her predecessors in African American popular music history through her voice, McLorin Salvant is not merely copying history or anyone from it. Rather, she is presenting a critical version of that history—one that challenges and erases its silences, while correcting it and re-writing those silences (and silenced ones) back in through song.

I should add that, in addition to the comments above, Ratliff and many other writers have showered due praise on McLorin Salvant. My purpose in referring to just a few passages is not to skew their characterizations or to advance a biased argument. I only wish to point out that writerly choices such as "unusual" over "unique" and "mimicry" over "mastery" demonstrate that, even though the repertoire that McLorin Salvant performs is historical, the questions she asks are not. As writers, audience members, and artists, we must be particularly careful to remember the silences and not to reproduce the stereotypes Valaida Snow and others resisted—the ones McLorin Salvant revisits, repeating them, and their triumphant critiques, with variation and difference.

* * *

After I had listened to WomanChild extensively and taken all the notes that led to this essay, I had the opportunity to talk with Ms. McLorin Salvant about her album. It was less an interview and more a conversation…about shared musical influences, jazz history, and our favorite baroque composers and Japanese restaurants in Manhattan. I offered up some of my interpretations of her work to solicit her responses and we discussed her artistic process in regards to a few of the tracks. We talked for well over an hour, but, after all the questions she had raised for me in this album, there was one specific question I had to ask her before leaving: "what does undone mean to you?"

During the course of our conversation, I think we both marveled at the resonant confluences and sympathetic flow we shared about WomanChild, jazz, and African American cultural history, but, in regards to "undone," we were not immediately in sync. What ensued after this initial difference was just the kind of conversational moment that "Deep Dark Blue" and WomanChild can inspire: after Ms. McLorin Salvant recorded the album, after I had listened through it countless times, and after we had been recounting our mutual experiences through her art, we had a much more in-depth and polyphonic conversation. Surprised and caught off-guard ("No one's ever asked me that before!"), her response was tinged with a questioning tone, "Well, at first, it definitely referred to death. As the process went on, it became less specific—more of a slipping away. But definitely downward…a downward slipping away." When she finished, she asked me what I was thinking and, to our mutual wonder and surprise, we riffed and elaborated on a more expansive and decidedly more positive association:

To my ears, "becoming undone" can also refer to something like self-awareness and freedom achieved through perseverance and struggle. Undone is Valaida Snow's graceful yet utterly complete subversion of "jungle music's" racial stereotypes. Undone is the personal resolve "Nobody" finds amid a lifetime of betrayal and ostracization. John Henry undoes death—even though he can't avoid it—through constant toil, winning the love and admiration of one woman-in-red…and entire generations who continue to recount his tale of perseverance and resolve. This idea is at the music's center in WomanChild as well: McLorin Salvant undoes a little bit of jazz history—and its naively saccharine love songs—by phasing in and out of canonical repertoire, filling out its sometimes myopic vision by adding back in forgotten and silenced repertoire from the whole history of African American music.

During our conversation, McLorin Salvant admitted to an artistic intrigue with death, as well as personal questions about her place and belonging in the African American and Afro-diasporic histories she works through in WomanChild. Hearing this, WomanChild's ubiquitous ticking clock takes on a whole new meaning! McLorin Salvant's manipulation of time and tempo suggest to me that she is, in fact, repeatedly undoing time in the album—slowing down the ticking clock, adding rubato phrasing, singing across the barline, changing tempos, interrupting and breaking open l'heure lointaine, unveiling le front caché, and making sure we don't just hear the words, but the consonants, too. She does all this so that she can communicate to her audience and work out these personal and culturally important questions about African American and Afro-diasporic art and identity in her own manner and time.

[Author's note: I'd like to thank Jordy Freed and Don Lucoff of DL Media, Al Pryor of Mack Avenue Records, and most especially Cécile McLorin Salvant for their time and assistance in my preparations for this piece. For more on Cécile's music, see my review of her NYC album release concert at 54 Below here.

Click on the image below to purchase a copy of WomanChild.

Mark Lomanno--a Mellon Foundation/Consortium for Faculty Diversity Postdoctoral Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of Music at Swarthmore College--teaches courses in ethnomusicology, jazz, music of the African Diaspora, U.S. popular music, and Western European classical music. He currently serves as the Co-Chair of the Society for Ethnomusicology's Special Interest Group on Improvisation. Lomanno's research focuses on improvisation as both a musical and cultural process and its application in interdisciplinary, collaborative, and community-based scholarship and pedagogy. His current projects include ethnographic and performance work in the Canary Islands and a monograph on the intersections of teaching, scholarship, and musical performance in jazz studies. In addition to a longtime piano trio project, his career as a jazz pianist includes the recent recordings 'Tales and Tongues' with Le Monde Caché, a San Antonio-based jazz group that plays Brazilian, Afro-Latin and Jewish diasporic repertoire; and 'Celebrate Brooklyn II', a collaborative release of Afro-Latin jazz with Canarian saxophonist Kike Perdomo. Mark maintains a blog, "The Rhythm of Study" (rhythmofstudy.com) that focuses on jazz and improvised music in the arts, academia, and social advocacy.