"Out for Presidents to Represent Me": The Breakfast Club, Hip Hop, and the 2020 Elections

With the rise of digital technology, images of Black people murdered at the hands of law enforcement have inundated various media outlets and influenced a surge in social activism. Recent protests, spearheaded by Black Lives Matter (BLM), have pressured America and its lawmakers to reckon with its “peculiar institutions” rooted in white supremacy and systemic racism (Wacquant 2010). Although active since the 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman (who murdered 17-year-old Trayvon Martin), the movement has catapulted into the mainstream, most recently in the wake of uprisings triggered by the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless others. Such tragedies have led many hip hop artists to speak on the current state of affairs, often communicating their political views via social media, interviews, and— of course—their lyrics. This concept of rap with a message attests to the multidimensionality of hip hop, how it merges the aesthetics with the politics (Rabaka 2001), and how such lyrics transcend time, especially as it relates to the Black experience in America. A recent example of this was the updated rendition of “Fight the Power” (released in 1989) performed by Public Enemy at the 2020 Black Entertainment Television (BET) Awards. The performance, which also featured Nas, Rhapsody, and YG, was filled with politically laced lyrics and imagery from protests across the nation. Additionally, the performance was evermore impactful given the show was simulcast on CBS, showcasing this powerful stance to a wider audience.

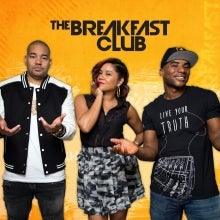

Along with artists, hip hop journalism has also contributed to propelling the culture into the mainstream with the likes of The Breakfast Club, a nationally syndicated hip hop radio show hosted by DJ Envy, Angela Yee, and Charlamagne Tha God. Since the 2016 election cycle, the show’s credibility has gained the attention of many elected officials in local, state, and federal levels of government. Moreover, the show has become a source for politicians seeking to connect with Black voters of the hip hop generation. In the 2020 race for the White House, the hosts of The Breakfast Club, most notably Charlamagne Tha God, insistently questioned candidates about their “Black agenda.” The notion of politicians embracing a policy platform specifically for the Black community is a demand that has grown increasingly popular since Donald Trump’s election in 2016. The Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), for example, is a strong national coalition of community organizations (including BLM) fighting for racial justice and human rights. The M4BL released a comprehensive policy agenda titled “Vision for Black Lives 2020” (updated from the 2016 demands) that comprises the following six planks: End the War on Black People, Reparations, Divest-Invest, Economic Justice, Community Control, and Political Power (m4bl.com).

Recognizing the significance of The Breakfast Club to hip hop and its ability to center the Black experience, I conducted a study that examined interviews from the current presidential election cycle and found that 15 candidates (Democrat and Republican) appeared on the show. The study surveys how hip hop, and in this case hip hop journalism, is used as means of connecting to Black people and whether presidential candidates consider a Black agenda that is in conversation with the M4BL policy demands. Each of the 15 candidates discussed pressing issues in the Black community as well as policies they support that relate to their Black agenda. The most frequently addressed issues were reparations, education, criminal justice, and healthcare.

Democratic Presidential nominee Joe Biden was the last candidate to appear on the show. The interview was filled with contention, perhaps provoked by Charlamagne’s criticism of Biden at the onset of the interview. Charlamagne shared with Biden hip hop icon Sean “Diddy” Combs’ perspective on the Democratic party:

He said what a lot of Black voters, what I believe, feel is that Democrats take Black voters for granted...I just want to know what candidates would do in exchange for our votes. Do you feel that Black people are owed that from the Democratic party?

Biden responded “Absolutely,” then proceeded to discuss his overwhelming win in the South Carolina primary, which was the turning point in the 2020 Biden campaign as Senator Bernie Sanders was previously leading in the polls.

The Breakfast Club host went on to ask Biden, “Why so much resistance on admitting the Crime Bill [of 1994] and other legislation you were a part of as damaging to the Black community?” Charlamagne added that unlike former Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, Biden was unwilling to reconcile the disproportionate impact of the bill on Black people. The Crime Bill of 1994 ushered in draconian measures (i.e. three-strikes rule, elimination of higher education in prisons, adult prosecution at fourteen, etc.) and had severe consequences for Black and Brown youth (Kitwana 2008). Biden justified his support by indicating that the issue was in fact the sentencing laws, and not the overall bill itself.

At the end of the relatively short 18-minute interview, Biden expressed that, “If you have a problem figuring out whether you are for me or for Trump, then you ain’t Black.” This statement essentially equates being Black with voting for a Democrat and also suggested that Black people are politically monolithic. Moreover, this type of rhetoric echoes Diddy’s sentiments, that Black voters have by enlarge been steered into voting blue since the signing of the civil rights legislation under the Johnson administration. The comment is also perhaps the most direct evidence of how politicians, among others, use The Breakfast Club as a legitimate, mainstream means of connecting with Black people through hip hop culture.

Questions fielded by the hosts of The Breakfast Club indeed addressed tenets of the M4BL policy agenda. In addition to conveying elements of their Black agenda, two other observations illustrated how candidates pandered to the show’s Black audience. First, some candidates invoked the name of revered Black activists or personalities, like Dr. Martin Luther King or Serena Williams. Second, the candidates spoke more candidly, even cursed, as means of seeming more relatable. For instance, Sen. Kamala Harris used a widely known hip hop proverb to illustrate the importance of electoral politics: “Don’t hate the player, hate the game. Elections matter.” The proverb stakes the claim that a person (one who expresses the statement) isn’t to be blamed for the way a particular system works. Essentially, Harris’ use of the proverb implies that voting acts as a means to reform the system, rather than change it altogether.

Hip hop culture has historically taken a firm stance in urging people, specifically Black voters, to be active participants in the electoral process (i.e. Vote or Die, Respect My Vote, etc.). Yet, the impending 2020 Presidential Election has left an air of uncertainty, especially when examining the remaining candidates and what they will do for the Black community. Irrespective of the incumbent’s Democratic opponent or who ultimately wins in November, it is crucial that the demands to make Black lives matter in America remain steadfast. Given its rise as a political pit-stop, it is clear that The Breakfast Club serves as a conduit for discussions pertaining to a Black Agenda, and by extension—human rights—using hip hop as the intermediary. The presidential candidates who appeared on The Breakfast Club recognize hip hop as the medium to connect with a segment of Black voters. And so hip hop remains a driver of the Black political voice while The Breakfast Club continues to advance the culture.

References

Kitwana, Bakari. 2020. The Hip-Hop Generation: Young Blacks and the Crisis in African-American Culture. New York: Basic Civitas Books.

Rabaka, Reiland. 2001. The Hip Hop Movement: From R&B and the Civil Rights Movement to Rap and the Hip Hop Generation. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Taylor, Steven J., Robert Bogdan, and Marjorie L. DeVault. 2016. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods a Guidebook and Resource. New Jersey: Wiley.

Wacquant, Loïc. 2001. “Deadly Symbiosis.” Punishment & Society 3(1):95–133.

Tabia Shawel is the Assistant Director with the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies. Ms. Shawel oversees the Bunche Fellows Program that serves as a pipeline for scholarship exploring various aspects of Black life—from microbiology to musicology. Her research has broadly centered on hip hop as a political expression. Specifically, she examines the re-emergence of political hip hop in mainstream media outlets and how it serves as an entry point for human rights discourse and political action. She holds a Master’s degree in Justice Studies from San José State University and intends to pursue a doctoral degree.