When Non-Western Music Sounds Psychedelic: Producing Thai Marching Band’s Cover of a Black Sabbath Song

Does Non-Western music sound more familiar under the label of “psychedelic”? Does the label become less efficient once applied outside of the original realm of the 60's California counterculture? While widely used by music critics, it isn’t risky to say that “psychedelic” has become an equivocal term. But equivocal doesn’t mean ineffectual. This paper focuses on Thai music media labeled as “psychedelic.” By media, I mean an artifact through which music is mediated, mainly through the process of commodification – be it on a large scale or not – such as CDs, tapes, records, but also digital files.

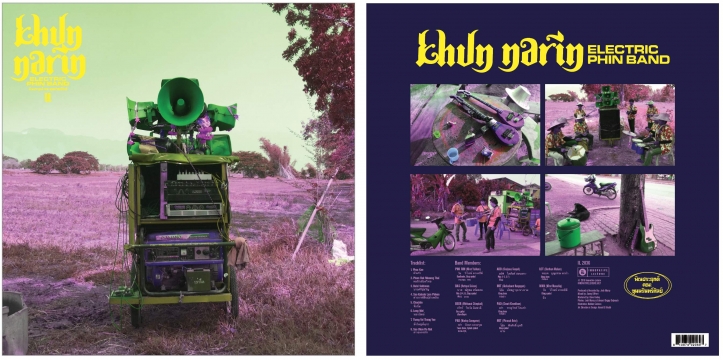

In December 2015, Khun Narin Electric Phin Band, a Thai marching band, was invited to play the Transmusicales de Rennes Festival in France. In 2011, after posting a self-made promotional video on YouTube, the band was introduced to a network of American record diggers and music enthusiasts. Ensuing video posts of parades in which the troupe covered “Zombie” by The Cranberries later instigated Josh Marcy, a sound engineer from Los Angeles, to come to Thailand in 2014 and record the band’s first album.

Video 1: Different footages of Khun Narin Sin Phin Prayuk parades, the band starts to cover “Zombie” by the Cranberries at 3'00 - video by Beer Sitthichai, Phetchabun Province, 2012

When they came to France, the band gave several interviews. I was there with Peter, a friend who knew the band before they visited Europe. We were supposed to help with translation from French to Thai and from Thai to French. During an interview given to the French newspaper Ouest-France, Khun Narin Electric Phin Band was asked the following question: “When people talk about your music, some say that it is something psychedelic, do you agree with that?” As there is no word for “psychedelic” in Thai, we asked them if they knew what “psychedelic” meant. Peter offered to give the following definition: “psychedelic is a kind of art associated with people who take medication, medication that dazzles your mind” (“psychedelic pen style silapa thi khon thi tit ya, ya bep, ya hai mao”). Totally surprised and a bit offended, Narin, the manager of the band answered the question with another question “Before playing music?... in my band, nobody takes drugs.” As I translated Peter's explanation to the journalist, she suddenly felt embarrassed and said: “oh no, no, I am not asking them if they take drugs,” while pointing at the album cover that the band didn’t get to choose. “…it's just that, how can I say, on the cover...”

Whether their music sounds druggy or psychedelic is part of a long-standing debate, which emerged in the comment section of Khun Narin’s first video post on Dangerous Minds’ website, under the title “A Mind-blowing Psychedelia from Thailand.” It is surely not very accurate to define psychedelic music as drug-induced music, but drug-enhanced or not, the band claims to have nothing to do with psychedelia.

One night of 2015 in a hipster coffee lounge in Bangkok, I thought I found some evidence of psychedelia. I was chatting with Pam, the bass player of a famous Northeastern Thai style revival band, who was also touring around the world. We were attending a DJ session and I was casually talking about psychedelia, when Pam reacted referring to a notion of “true Thai psychedelia.”

I felt totally dazzled by his answer. I had just been fruitlessly looking for an emic conception of psychedelia for more than a year, and it turns out, I could have simply asked the members of the upcoming Thai revival music band about it. I dared to ask Pam for more evidence, such as what kind of bands he was thinking about. Pam was not so sure and simply said that a Swedish guy had compiled such stuff on a record called Thai-Beat A Gogo (2004). As Maft Sai, the owner of the bar, stated in the booklet of a compilation of Thai 60's and 70's music:

“It's possibly a misnomer to label music recorded outside of the USA or Europe with terms such as 'psyche' or 'surf' as it is often just a stylistic innovation based on exposure to foreign records via the radio or music stores. It doesn't necessarily chime in with any of the social shifts or changes that accompanied the music's development in the West.”

Video 2: After it was first published on YouTube, this video of the band quickly became viral among music enthusiasts of the Western blogosphere - video by Sumeth Yahkham, Phetchabun Province, 2011

While it is hard to find evidences of a local style of psychedelia in Thailand, why does the word psychedelia stand as a gimmick for the diffusion of Khun Narin’s music?

In order to answer this question, I will focus on the production of a Black Sabbath cover song by Khun Narin. My aim is to show that the production of new media labeled “psychedelic” in Thailand is itself rooted in the circulation of older media. To that extent, I will argue that the production of psychedelic-like artifacts challenges the ways World Music used to promote Non-Western music as radically different. Finally I will conclude with some considerations about the role of media in this process.

I. Producing a cover of Black Sabbath:

After his visit in 2014, Josh Marcy came back to Phetchabun in 2015 to record a second album. The first album was successful, critically and commercially speaking, for such a small independent music label as Innovative Leisure. But this time Josh wanted to go a step further, so he came back to Thailand with a more personal request. Aside from the project of recording a new live session, Josh wanted the band to record three covers among which was a song by Black Sabbath titled “Planet Caravan.” From an artistic point of view Josh was totally at ease with his personal motivations and preferences: “selfishly it's something I would like to hear... I mean, you know it's hot stuff, sure unlike those other things that we get from them, but the point is... that you have to trust taste.” As I already knew the band, and as Josh was looking for a translator, I was there trying to help Khun Narin and Josh understand each other. According to Josh “[the band] just [had] to borrow the bass and the structure, then they just [had] to do their riff!”

The bass player easily got the rhythm as Josh, who is also a bass player showed him the pattern on his instrument. The lead musician Aob, who plays a string instrument called the phin, had a more difficult time because the phin has a shape slightly different from a guitar. Aob and Josh managed to find the scale on the instrument. When they did, Josh became very enthusiastic. While Aob was practicing the guitar pattern he had just learned to play with his phin, Josh showed everyone a picture of Black Sabbath on his smartphone crying out: “that's who we're paying tribute to [...] Black Sabbath, 1970, Ozzy Osbourne ... that's rock!”

Photo 1: Josh showing Black Sabbath pattern to Beer on bass guitar – Photo by E. Degay Delpeuch, Phetchabun Province, 2015

The band then brought out the sound system: a 600kg iron tower made of heavy bass speakers and a bouquet of eight mid-range and high-frequency speakers on the very top of it. The machine impressed Josh. I was there, sitting by the scene waiting for what would happen next as Josh declared: “Oh, it's gonna work so fucking well.”

Josh said “you've got to trust taste,” but since taste is subjective, it doesn’t offer an objective explanation for why an independent music producer from L.A. came to Thailand to record a local band covering a Black Sabbath song. To understand the production of this new media, one has to understand that it is folded into the production of older media. Indeed, Khun Narin had already broadcast covers of Western popular songs on the Internet, such as “Zombie” by The Cranberries.

Thai musicians such as the popular luk thung singer Sroeng Santi already recorded a cover of Black Sabbath “Iron Man” under the name “Khuen khuen long long.” It was recorded in the late 70’s and has been reissued in 2011 on the compilation album titled Thai? Dai!, which was assembled by record diggers Andy Votel, Chris Menist, and Maft Sai.

Video 3: First Thai cover of Black Sabbath hit “Iron Man” has been reissued on Finders Keepers Records in 2011

II. Production of New Media folded in the Production of Older Media:

Thai? Dai! (2011) was released during a resurgence of compilation albums that also featured Non-Western pop music from the 60-70’s. All orchestrated by a rather small network of record diggers, vinyl collectors, publishers and DJs, who have had a significant role in putting the term “psychedelic” in circulation. To some extent, this small network is involved in what David Novak describes as “a recent intervention into the circulation of ‘World Music’.” This intervention is “based in the redistribution of existing recordings of regional popular music – most of which already bear a strong formal and technological relationship with Western popular culture – as a ‘new old’ media.” (Novak, 2011: 605).

Ben Tausig, ethnomusicologist and author of a critical study about music and the broadcast environment of Thailand's Red Shirt movement and occasional music critic of Dusted Magazine (2011), gives us the following insight about the Thai? Dai! compilation album:

“[...] When Sroeng Santi’s “Kuen Kuen Lueng Lueng” leads off this comp by launching unapologetically into the riff from “Iron Man,” [...] you’re being flattered [...]. Just as the heavy bass and fuzzy guitar will remind you of indigenous European psychedelia, you’ll hear in these musical citations confirmation that the appeal of early metal [...] was as universal as you suspected. But the truth is that Thai listeners, while frequently charmed by Western music, are not necessarily listening in ways or to the things you might expect. [...] Thai? Dai! is not so much a retrospective of a forgotten Thai musical past as it is a report from a thriving but ultimately small cosmopolitan present, from a scene that’s had to filter through a lot of records to find the songs that fit its prefigurations of taste.”

Both Sroeng Santi's cover of “Iron Man” and Khun Narin’s music convey a significant shift in the way Western music enthusiasts are now listening to Non-Western music. The radical difference that characterized how World Music was introduced to Western listeners is no longer working as a source of interest for them. To some extent, if Western listeners were looking for World Music as an authentic source of alterity, now they are looking for media as an authentic source of World Music. Indeed, figuring ourselves in a world strongly ruled by the market economy, the commodification of music now gives the ultimate proof that this music has not been produced in the West for us, but elsewhere for somebody else. Paradoxically, by looking for media as an authentic source of Non-Western music, Western listeners find out that music produced elsewhere in the world might not be so different from their music.

Ben Tausig talks of “a scene that’s had to filter through a lot of records to find the songs that fit its prefigurations of taste.” Indeed, if media is now working as a mechanism that guarantees the authenticity of music, authenticity itself is relocated through select media.

III. Make it whose own style?

I would like to give a final insight about how authenticity is finally relocated under the case of Khun Narin. From the point of view of Josh, reproducing an identical replica of Black Sabbath was not really satisfying. The band needed to make it “their own style.”

When I asked Aob the luth player to play Black Sabbath in their own style, he confirmed by reiterating: “You want the Khun Narin's style, but with this song, right?” “Ok, so it will go into hip-hop,” Aob hummed a hip-hop rhythm “toop, top, toop, top.” The band rehearsed several times the first four bars of “Planet Caravan” introducing small variations such as a distortion effect and a hip-hop rhythm, while stopping at every step to ask Josh for his consent. “Could we introduce molam (Lao traditional music)?”, “could we introduce a disco step after [the] hip-hop [section] and before molam?” Josh listened to each proposition but did not really feel satisfied with the molam pattern Aob played. Moreover, just switching from one rhythm to the other did not really meet Josh's idea of the band doing their “own thing.” While Josh was listening to Aob repeat the first four bars of “Planet Caravan,” he pointed out that “it would be nice if he took a solo and did his own thing, you know what I mean? … like on the song, there's the bass line and just take a solo on this.”

But the more I asked the band to play “according to their own style” the more I realized that everyone was getting more confused. Josh commented that “I just want them to play ‘Planet Caravan’ in their own way … you know what I mean, rather than a medley … they can just do that song—I don't know how just to describe [it] to him—you know, just do a solo, [and] start playing his own melody all over that.” Listening to Josh's request, I felt embarrassed finding the words to translate it. How could I communicate what Josh meant by a “solo”? The word “solo” did not sound unfamiliar to the band, but for them the word suited for any specific sequence of fixed notes that might introduce variations in the long sequence of songs that composed their medley, such as a molam introduction or the first four-bar of the Black Sabbath song. In other words, while I was deliberating the word “solo” in order to lead them to produce an original melodic variation, the band just wanted to switch from one fixed sequence of notes to another. The idea that asking the band to play a “solo” would then lead them to improvise was not obvious. Even more confusing was the idea that “their own way” was something else than a medley.

Photo 2: Khun Narin II recording session, Narin at the control panel – Photo by E. Degay Delpeuch, Phetchabun Province, 2015

Conclusion: Discovering a missing link: Short-circuiting the feedback

Neither Josh Marcy nor Innovative Leisure ever made the assumption that Khun Narin was influenced by psychedelic or heavy metal music. Unlike some of the simplistic understandings of Khun Narin’s music, Josh once stated the following in Newsweek (2014), after the first album of the band was released:

“I don't believe that they were influenced by psych rock as we would think of it. … It just happens to have turned out in a way that sounds familiar, in that vein, to us. They'd never heard the Grateful Dead or things like that.”

However, after the rehearsal session and without any real satisfying solo to record, Josh came back to me pointing out a missing link that made the cover of Black Sabbath so difficult:

“you know [...] the missing link in the heritage of their music [...] is the Blues, [...] you play a melody, you sing a melody and then you solo [...] and you play it different every time, there is a way maybe you've worked it out [...] but it's funny without a reference of the blues, as like a starting point, it's hard, you know, you can't go back to any sort of bedrock [...].”

Given that Thai musicians have created wonderful pieces of music that sound familiar to psychedelic music lovers, the circulation of a specific selection of older media also leads to the assumption that every psychedelic-sounding music in Thailand, such as Khun Narin's music, might be hiding deeper musical connections. But the illusion of Thai guitar heroes just lies in the distance.

To some extent the international circulation of Thai music under the label of “psychedelia” works as a “feedback” from West to East, then East back to West. To that extent there is no place where “Thai psychedelia” is produced, except in the international circulation of select media. While in the topic of “feedback,” I would like to refer here to David Novak's recent study on Japanoise in which he describes a musical phenomenon similar to “Thai psychedelia”; the notion of a musical identity that lies in the distance but vanishes in proximity:

“[...] for two decades, Japan was where Noise stuck—not because Noise was invented there, but because it was driven home in transnational circulations that continually projected its emergence back onto Japan. [Japanoise] I argue, could only have been produced through this mediated feedback between Japan and North America.” (Novak, 2013:16).

Photo 3: Khun Narin II album cover design - Innovative Leisure, 2015

Media allows the circulation and communication of a musical phenomenon without this phenomenon needing to be understood within its cultural context. Media can operate through labels such as “Japanoise” or “Thai psychedelia,” because nobody needs to put their tastes to the test with the musicians in the way Josh did.

Indeed, the feedback works as long as no “test”, no convergence happens, which might bring to light the fact that psychedelic sonorities are not hiding psychedelic heroes. Thus, when convergence happens, missing links are discovered and function as short-circuits. Therefore the absence of convergence is the essential key to understand the way a word such as “psychedelic” might determine the international circulation of cultural references.

Bibliography:

Fader, L. (2014). Khun Narin's Electric Phin Band: The Psychedelic Rock Band Discovered in a Remote Village in Thailand. Newsweek, [online]. Available at: http://www.newsweek.com/khun-narin-phin- sing-psychedelic-rock-band-discovered-remote-village-thailand-266649

Menist, C. and Sai M. (2010). The Sound Of Siam: Leftfield Luk Thung, Jazz & Molam In Thailand 1964-1975. [booklet] Soundways.

Novak, D. (2011). The Sublime Frequencies of New Old Media. Public Culture, 23(3), pp. 6-7.

Novak, D. (2013). Japanoise, Music at the Edge of Circulation. Durham: Duke University Press.

Tausig, B. (2011). Dusted Reviews, Thai? Dai!: The Heavier Sound of the Luk Thung Underground. Dusted magazine, [online]. Available at: http://www.dustedmagazine.com/reviews/6356.

Edouard Degay Delpeuch is a Ph.D candidate in anthropology of music at the École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociale, Paris. His research makes a special ethnographic case of a Thai marching band internationally known as Khun Narin Electric Band. From Thailand to the World, his research focuses on processes that create music through circulations and renegociate cultural boundaries through music. Edouard Degay Delpeuch is a member of the Georg Simmel Research Center and an associated member of Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CASE).