From Oppression to Opportunity to Expression: Intercultural Relations in Indigenous Musics from the Ecuadorian Andes

Biography

Juniper Hill holds a Ph.D. and M.A. in Ethnomusicology from UCLA, and a B.A. with High Honors in Music and in Latin American Studies from Wesleyan University. She is a former Fulbright Scholar and has taught at Pomona College and the University of California, Santa Barbara. She has conducted research on traditional and commercial music in the Ecuadorian Highlands, on contemporary folk music in Finland, and on Anglo-American folk music and dance in the US. Her research interests include music resulting from interethnic and transnational relations, protest music, gender and sexuality, and relationships between music and dance.

Abstract

For the indigenous inhabitants of the community of Peguche in the Ecuadorian Highlands, daily life is permeated by interactions with mestizos, indigenous people from other regions, and foreigners from Europe and North America. These intercultural relationships are deeply intertwined with the community's musicmaking, in traditional music, commercial music, and personal music. Traditional music performed at festivals in the community reflects a long history of Incan-Spanish interaction. Today it plays a role in contemporary indigenous-mestizo identity politics and indígenas' struggle to overcome their stigmatized social status. Commercial music performed for and sold to foreigners in Europe and North America provides an opportunity for indígenas to circumvent the socioeconomic oppression within Ecuador. Traveling musicians returning home to the Andes with newly acquired wealth, worldly experiences, and heightened social consciousness impact local politics, racial hierarchies, and indigenous identities. Personal creative music performed in the private sphere allows indígenas' to express and cope with their cosmopolitan intercultural lifestyles.

Introduction

Just after sunrise on an early summer day, I sat at the small kitchen table chopping yucca roots while my host mother, Enma Lema, prepared the day's soup with water from the mountain stream (we had no running water or sewage system). At 9609 feet in elevation, the mornings could be cool; we were warmed by the blue glow of trash burning in the fireplace (there was neither central heat nor garbage collection). In the next room, her younger son sat on the dirt floor playing Nintendo, while in the back room her older son listened to Sting on the radio as he worked on the textiles that were to be shipped to Europe or sold to international tourists at the Saturday market. As Enma prepared food, she told me stories, in Quichua-accented Spanish, of the castle in which she had stayed in Switzerland, the universities at which she had performed in France, and the cold winter in Germany that had cut through her traditional indigenous dress. She had been a member of El Conjunto Peguche, one of the first Ecuadorian indigenous ensembles to perform abroad in the 1970s. Though Enma travels very little now, her family members, relatives, and neighbors travel regularly and frequently to North America and Europe to sell Andean music and textiles. These traveling musicians and entrepreneurs bring money, new ideas, and worldly experiences back to their Andean community, a community still struggling against poverty and ethnic prejudice in a mestizo-dominated country.

For the inhabitants of the small indigenous community of Peguche nestled under Mount Imbabura in the Highlands of northern Ecuador, contemporary everyday life is permeated by interactions with other cultures.1 These cultures include mestizo, North American, and European cultures, as well as indigenous cultures from other regions. Music plays an important role in mediating these intercultural relations, both in the Andes and abroad.2 In this paper, I discuss three types of music performed by indigenous musicians from Peguche: (1) traditional music performed at religious festivals and traditional ritual events in the community; (2) commercial music performed and recorded for foreign markets abroad; and (3) personal creative music performed for individual expression in the private sphere.3 Each type of music reflects the influences of past and current intercultural contact, and each serves as a strategy for empowerment in unequal intercultural relationships, whether through identity politics, through economic gain and the building of transnational alliances, or through personal modes of expression and coping.

The ethnographic data presented here are based on fieldwork I conducted in Peguche, nearby towns (Otavalo, Cotacachi, and Ibarra), and in Quito in 1996 and 1997, as well as on encounters with traveling Andean musicians in Connecticut (1997), New York (1998), Boston (1998), Pennsylvania (1999), Los Angeles (2000-2001), and Finland (2002, 2004).

Intercultural Relations in the Valle de Imbabura

Ecuador has eleven officially recognized indigenous peoples, constituting at least one fourth of the country's population.4 Many of the modern-day indigenous inhabitants of the Andean highlands in northern Ecuador proudly identify themselves as descendents of the Incas, speak Quichua (Incan language, also called Quechua A), and celebrate syncretic forms of Incan religious festivals.5 They refer to themselves as indígenas, "indigenous people," in Spanish and Runakuna, "people"(or Runa, singular, "person"), in Quichua. During the fifteenth-century expansion of the Incan Empire, the Incas conquered and assimilated the previous indigenous inhabitants of this region (perhaps the pre-Incan cultures partly account for the local specificity of traditions and customs and rich variety of regional differences in Andean indigenous communities). Traditionally, each indigenous community has had its own strong local identity and unique traditions. Recently, northern Andean indígenas have been forming alliances with other indigenous ethnic groups from within and beyond Ecuador, especially with groups from the Ecuadorian Lowlands and Amazon basin and the Peruvian and Bolivian Highlands, but also with native/indigenous groups from all over the Western Hemisphere. They are forging pan-Andean and pan-indigenous identities that stretch across the Americas.

In the Valle de Imbabura (a series of contiguous valleys over which towers Mount Imbabura), indígenas live in numerous small mountain communities, but they regularly descend for commerce and festivals to the three major valley towns, Otavalo, Cotacachi, and Ibarra, which are dominated by mestizos, and indígenas are governed by local and national laws that are determined largely by mestizos. Although the term mestizo means a person of mixed indigenous and Spanish lineage, in Ecuador, mestizos, or blancos-mestizos (white-mestizos), tend to be native Spanish-speakers who generally hold higher political and socioeconomic positions and who identify most strongly with their Spanish heritage (see also Stark 1981: 387-401).6

The current political, economic, and ethnic stratification between indígenas and mestizos has been shaped by a long history of intercultural interactions. Spanish colonialism lasted from 1534 to 1822 – nearly three centuries. During colonial rule, indígenas were forced to work under the encomienda system in which people of Spanish descent owned indigenous labor, and under the mita system in which the government required the tribute of indigenous labor (Burkholder and Johnson 1994). In the independent Republic of Ecuador, slave-like conditions continued with the huasipungo debt-peonage system for another 142 years until The Agrarian Reform Act of 1964 (CEDIME 1993; Bretón 1997). The aftermath of colonialism can still be seen in the social stratification, identity politics, and ethnic tensions between mestizos and indígenas at both local and national levels. Today, indígenas are struggling for rights in a country that in many ways continues to treat them as second-class citizens. Their perceptions and oral histories of their heritage and of the history of indigenous-mestizo relations are very influential in how they define their ethnic/cultural identity and in how they interact with other ethno-cultural groups.

Interaction with European and North American cultures has been increasing dramatically since around the 1970s. Numerous indigenous musicians frequently travel back and forth between Europe or North America and the Andes; family-run cottage industries ship textiles to relatives and friends living abroad for distribution in Western markets; hordes of foreign tourists flock to the Saturday market in the nearby town of Otavalo; and families follow TV and radio programs from South and North American countries. Ecuador's relations with the US and Europe also impact daily life in Imbabura. As a nation, Ecuador is poor and has little political power (for example, in 2002 Ecuador's Gross National Income [GNI, formerly GNP] per capita was US$1,490, compared to the United States 2002 GNI per capita of US$35,400 [World Bank 2003]). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) austerity policies, which were enforced while I was conducting fieldwork in Ecuador in the 1990s, led to increased prices on food and utilities and caused severe economic hardship on both mestizos and indígenas, leading to massive strikes and riots. However, capitalist entrepreneurship in international tourism and travel abroad has led to relative economic prosperity for many (though not all) indigenous individuals from Peguche and the Otavalo region.

The indígenas' ethnic/cultural identity and political-economic position is complexly intertwined with these different modes of new and old intercultural relationships, and, as I shall demonstrate, so is their music making.

Traditional Music

Indígenas perform what they consider to be música tradicional for festive and ceremonial events in their community. Traditional music performance practices reflect historical processes of intercultural negotiations and syncretism, they construct ethnic identity and distinguish indígenas and mestizos from each other, and they play a role in indígenas' contemporary struggles against mestizos.

Remnants of the Incan Past and of Spanish Colonialism

Indigenous festivals, traditional music, and traditional clothing differ from mestizo practices and vary amongst indigenous communities; yet they both contain elements originating from both pre-Columbian Incan traditions and Spanish colonial influences revealing intercultural interactions from centuries ago.

Plate 1. Symbols of pre-Colombian and Catholic beliefs in Inti Raymi: celebrants play gaita duets and dance beneath fruit offerings to the spirits and portraits of Jesus at the Last Supper and the Virgin Mary (the other gaita player and additional dancers are not shown in photo). The man in the center is wearing the mask and playing the role of Aya Huma, a mischievous spirit. Photo by J. Hill, June 1997.

Inti Raymi, also known locally as Fiesta de San Juan or Fiesta de San Pedro, is the most important religious/cultural festival of the year to the indígenas in the Valle de Imbabura. The name of the festival itself chronicles the struggle between indígenas and Spaniards. In Quichua, Inti means "Sun," an important god of the Incas, and Raymi means“festival.” As an Incan religious festival, it celebrates both Inti and corn, the sacred crop of the Incas. The celebration continues for several weeks during the summer solstice period. Under pressure from Spanish Catholic missionaries, the festival was renamed in Spanish for Catholic saints whose holidays corresponded with the dates of the festival. In Peguche it is known in Spanish as Fiesta de San Juan (St. John's Festival), while in some other communities it is known as Fiesta de San Pedro (St. Peter's Festival) or Fiesta de Santa Lucía (St. Lucy's Festival). The renaming of Inti Raymi for a Catholic saint also served as a strategy to disguise the Incan festival as being Catholic, thus allowing indígenas to continue to honor their Incan heritage (over time, there came to be a syncretism of religious beliefs in addition to names and customs). [See plate one] During Inti Raymi in Peguche, indigenous musicians perform two important types of traditional music: duets played on gaitas (transverse flutes made of cane) and string ensemble dance music. Generally, the majority of indigenous wind instruments in the Andean region, including a huge variety of flutes, pan pipes, and simple trumpets, are pre-Columbian in origin while most string instruments, including violins, guitars, and harps, were introduced by the Spanish and other European missionaries and colonists (Moreno 1972: 83-85; see also Schechter [1992] for a detailed history of the indigenous use of the harp in this region and elsewhere in Latin America).

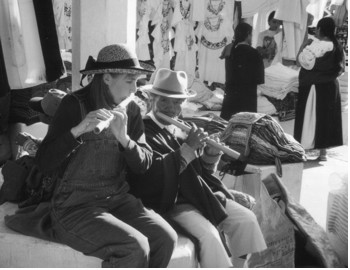

Plate 2. The author and community elder Marcos Lema, a.k.a. Papa Marcos, practice gaita duets in the days leading up to Inti Raymi while Papa Marcos tries to sell his handmade scarves at the Saturday market in Otavalo. In the back right, indigenous women wearing traditional clothing barter over blouses. Photo by Stacey Parris, June 1997.

The gaita duets performed during Inti Raymi show the least amount of Spanish influence and highest amount of Incan retention, and their musical structure is shaped by traditional cultural practices and beliefs.7 [See a photo of a community elder and the author practicing a gaita duet in plate two]8 Gaita is the Quichua name for these flutes, while in Spanish they are called flautas de San Juan after the festival. Gaita duets are repetitive and polyphonic, in duple, triple, or additive meters, and accompany traditional dance and ritual processions. The songs have no ending, but rather are repeated until the two performers are overcome by other musicians who overtake them, causing the dancers to shift and circle the overtaking musicians and creating a continuous, richly textured, overlapping fabric of sound. [See musical example No. 1] Gaitas are played across the Valle de Imbabura, the tuning system varying from community to community so that each song is identifiable as belonging to a specific community. This local specificity, or uniqueness of each community, is a traditional indigenous characteristic known as cada llajta (cada = each in Spanish, llajta = village/community in Quichua) and is found across the Andes in indigenous music, rituals, clothing styles, and linguistic dialects (for more on cada llajta in the Valle de Imbabura, see Schechter 1996:458 and 1982:26).

Gaitas may only be performed in duets, never solo, and the two instruments being performed must have been crafted together as a matching set. According to local musicians and shamans, these gaita duets reflect the complementarity inherent in nature that is so important in Andean cosmology. They are often compared to the Sun God (Inti) and the Mother Earth (Pachamama) or to a husband and wife. I found these beliefs to be deeply ingrained in the musical practices of gaita players who either lived in very remote, isolated communities in the mountains or who were from the older generation. These musicians were unable or unwilling to play the individual parts of the gaita duets separately, even in private lessons outside of the ritual context. More cosmopolitan, younger gaita players, who had extensive interactions with other cultures and who performed several types of music, acknowledged that the gaita duets reflect traditional beliefs, but they did not strictly adhere to traditional performance practices when they were outside of public scrutiny by the community. They were willing and able to play the individual duet parts separately in private lessons with me. For both young and older musicians, traditional music is an important part of festivals and rituals. For older and less cosmopolitan musicians, music is also an enactment of their worldview or a former religious practice, whereas for younger, more cosmopolitan musicians this metaphor has receded but they continue to view music as an expression of their cultural heritage.

Musicians from Peguche perform another type of traditional festival music on violins and guitars, instruments that were introduced by the Spanish and subsequently appropriated by the indígenas. During Inti Raymi celebrations, string ensembles perform in the same context and manner as gaita duets, and together these different musical types create a richly textured fabric of sound as different ensembles overlap and overtake one another throughout the night. The string ensembles perform an indigenous genre of music called sanjuan, named after the festival's Spanish name. Though sanjuan is an important indigenous traditional music genre, it shows evidence of Spanish musical influence and has in turn influenced mestizo music. Melodically, sanjuanes are often characterized by pentatonic motives (a common trait in indigenous music) and alternations between major and minor modes (a common trait in indigenous music as well as in traditional Spanish songs [Miles and Chuse 2000: 593]). Guitar chords typically follow the melodic pattern and alternate between relative minor and major modes in thirds (for example, between E minor and G major, or Em to C to Em to G to Em), instead of following dominant-to-tonic Western functional harmony. Rhythmically, sanjuanes are recognizable by their sixteenth-eighth-sixteenth eighth-eighth pattern in 2/4 time. [see musical example No.2] The famous national (mestizo) Ecuadorian genre sanjuanito is derived from the indigenous sanjuan and uses the same rhythmic pattern (see Schechter 2000 for a brief description of how the sanjuanito and sanjuan differ, and Schechter 1982:246-247 and 1996:447-465 for more extensive musical analysis of the sanjuan).

Though the majority of indigenous and mestizo music is easily distinguishable by instrumentation and genre, with the majority of local mestizo festival music being performed on European brass and reed instruments (such as trumpets, trombones, clarinets, and saxophones), some indigenous and mestizo music is not so distinct. Mestizo music also reflects a history of Spanish and indigenous syncretism, and some mestizos play guitars and bamboo wind instruments. In these cases, my indigenous informants adamantly argued that their music differs fundamentally from mestizo music in what they call the music's "feeling," using an English loanword. It was extremely important for my informants that mestizo and indigenous music be distinguishable and distinguished.

The most explicit marker of indigenous identity for women, who are not instrumentalists, is their consistent, quotidian use of traditional clothing. (In contrast, most indigenous men, excluding elders, wear Western-style clothing, though they do often wear identifiably indigenous hairstyles.) Women's traditional clothing is another important marker of indigenous identity that reflects historical interaction between the Spanish and indígenas. Indigenous women wear elaborately embroidered blouses with frilly sleeves whose patterns indicate the home communities of the women wearing them. Today in Ecuador these blouses are synonymous with indigenous identity. It is not common knowledge in Ecuador that this clothing style descends directly from a popular style worn by Spanish women two to three hundred years ago (according to Maria Victoria Páez Freile, professor of Latin American art history at the Universidad de San Francisco de Quito who studies 18th and 19th-century colonial portraits and who showed me slides of paintings of the original styles before they were appropriated by indígenas). Indígenas were forced to make such blouses for Spaniards and mestizos in the textile sweatshops that once filled Peguche before these slave-like practices were outlawed. Today, mestizos wear contemporary Western clothing, a striking contrast to the traditional styles worn by indigenous women. [See women's blouses in plate two]

The Construction of Ethnic Identity and Difference

Despite the mixing of Spanish and Incan heritages in the historical evolution of indigenous festivals, clothing, and traditional music, these practices have been socially reconstructed as important markers of indigenous Ethno-cultural identity today, and they are now unambiguously interpreted by indígenas, by mestizos, and by foreign tourists as being specifically indigenous.

Many Ecuadorians still conceive of indígenas and mestizos as belonging to two different "races" (some particularly socially conscious indígenas speak of the prevalence of "the myth of the purity of indigenous race," or "el mito de la pureza de la raza indígena").9 In reality, there has been so much intermixing over the centuries that the majority of indígenas and mestizos can not be distinguished by phenotype. Rather, they are identified by cultural markers such as music, dance, language, dress, occupation, place of residence, and social status. Since ethnicity is determined more by customs and behavior (traits with some adaptability) than by biologically determined physical traits, individuals have some maneuverability in their ethnic identity. Some individual indígenas actually "become mestizo" by changing their clothing, hairstyle, and language, leaving their indigenous customs behind, and migrating to an urban center as a strategy of escaping the stigmatization and oppression that accompany the ethnic identity of indígena, or, to use a slightly derogative term, Indio (Indian).

The construction and manipulation of ethnicity in mestizo-indigenous power relations have been well-documented by Zoila Mendoza (2000) and Thomas Turino (1993) in Peru, where the historical and cultural situation is similar to that in Ecuador. Initially, maintaining separate ethnic/racial identities aided Spaniards and mestizos in maintaining power over indígenas. Emphasizing racial or ethnic differences served to naturalize and legitimize the oppression and exploitation of indígenas. According to Mendoza, "[colonial] authorities were interested in keeping as much of the population as possible classified under the Indian casta because they could collect taxes from them and have access to their labor" (Mendoza 2000:13). Turino explains that:

the 'Indian' identification was partially constructed and maintained by the colonial and republican states, and by members of local elites, in order to retain the indigenous segment of the population as serfs, as a labor pool for the mines, and for tribute payment... People and cultural practices identified as 'Indian' have been systematically separated out, marginalized, and oppressed by the state and local elites for much of Peru's history. Often denied access to opportunities and upward social mobility within the larger society, indigenous Andeans in Southern Peru bolstered their own social unity at the local level as a means of defense. (1993:20-21)

Both Turino and Mendoza discuss the ambivalence that indígenas feel between being ashamed of their stigmatized indigenous status and being proud of their indigenous cultural heritage when performing indigenous music and dance.

In Ecuador, Spaniards and then mestizos have monopolized the power of representation of indígenas, appropriating and manipulating the images of indígenas for their own social and political purposes, from colonial times through Ecuador's struggle for independence from Spain through 20th-century political movements (Muratorio 1994:9-21). Now indígenas are questioning their stigmatized status and fighting for control of their own cultural representation, in part by taking pride in their indigenous identity and in their traditional music as a marker of that identity.

Traditional Music in Contemporary Indígena-Mestizo Relations

I found that many indígenas from Peguche consciously worked to maintain their cultural heritage and present a positive image of indigenous culture to themselves and to outsiders. I see this as a form of cultural resistance for three reasons. First, indígenas are choosing to keep their indigenous identity, despite its lower social status and limited life opportunities, instead of attempting to assimilate and pass as mestizo. Second, indígenas are asserting their right to construct their own identity, instead of having it constructed for them by a mestizo hegemony. Finally, they are taking pride in their ethnic/cultural identity and working to change the negative stereotypes associated with indígenas into positive representations.

The first musical groups to travel abroad in the 1970s had a cultural agenda: they wished to portray a positive image of indigenous culture to the rest of the world. My host family and many of my indigenous friends were extremely concerned that such musicians be skilled and knowledgeable about traditional music so that they would represent indigenous culture well to others. Musicians thought to be lacking the knowledge or skills necessary to perform traditional music were often criticized for misrepresenting indigenous culture to foreigners. Many indigenous community members had a keen awareness of threats presented by mestizo and Western cultures and of the need to actively maintain and preserve their own music and culture.

In addition to the continuous struggles to represent, define, and sustain indigenous music and culture, some of the struggles between mestizos and indígenas over indigenous culture are physical. In the festivals of Inti Raymi, each indigenous town or community has its own unique music and way of celebrating, and their festivals often have different names in Spanish. In Cotacachi, a nearby town across the Valle de Imbabura, the fiestas de San Pedro exemplify indígenas resisting mestizo attempts to put a stop to a traditional indigenous festival. Indígenas continue the Incan tradition tinku, an annually expressed ritual battle between indigenous groups. In June, 1997, I went to observe this festival with my host family and other friends from Peguche (indígenas from other communities typically come to watch the rituals). Groups from indigenous comunas, communities in the mountains above the town, gathered together with musicians, costumes and props and descended to the Main Plaza in the mestizo town of Cotacachi. The musicians played gaita (transverse cane flute) duets and conch shell trumpets. They were surrounded by dancers who wore militant costumes and carried whips and stones. When the participants reached the Plaza, each group played flute music, chanted in unison, marched-danced around the Plaza, and competed against other indigenous groups from other communities. This ritual was violent: the stones and whips were not just props but weapons used in combat against the other groups. There were many injuries and I was told that it is not unusual for one or two people to die each year. My indigenous informants from Cotacachi recognize this ritual as one of their traditions that has been continued from the time of the Incan Empire. Bolivian scholars discussing the meaning of tinku on the Bolivian altiplano, in the southern part of the former Incan Empire, define tinku as: an encounter, a ritual battle between opposing groups within the same community or between communities, a union or coming together of enemies, an equalization, a meeting of people or things coming from different directions, and also a sexual or romantic encounter. The ritual battles of tinku are important because they provide for an exchange of power necessary for maintaining the social equilibrium, they regulate internal tensions within the group, they reaffirm territorial and familial boundaries, and they bring harmony and agreement (Harris and Bouysse-Cassagne 1988:241-242, Cereceda 1988:342, Platt 1988:392).10

In the Valle de Imbabura, indígenas and mestizos have confronted each other legally and physically over the indígenas’ right to maintain their traditions in the space they share with mestizos. Cotacachi's mestizo mayor and town administrators do not appreciate having this violence in their downtown every year (the violence is not directed at mestizos, but it is highly disruptive and sometimes mestizo property is damaged). When I was there in 1997, they delivered proclamations and took measures in an attempt to stop this festival, but ironically, in their attempts to stop these ritual battles, they joined them. However, they did not play by the indígenas’ rules, and their uninvited participation in the ritual battle only escalated tensions instead of relieving them. Under the strong Equatorial sun in the Main Plaza of Cotacachi, the music of bamboo flutes, conch shells, and dancers'/fighters' chanting was periodically interrupted by screams as mestizo policemen, also garbed in militant clothing, dropped tear gas on indigenous participants and observers who ran away screaming in every direction.11 When the tear gas cleared, indigenous groups and observers returned to the Plaza and continued the ritual until more tear gas was released and the cycle continued.

Similar ritual battles used to be celebrated in the nearby town of Otavalo until they were stopped by force in the 1960s by Otavalo's mestizo police force with the help of police and soldiers sent from the provincial capital Ibarra (Buitan and Collier 1971:101). In Cotacachi, indígenas continue to resist mestizo authorities who wish them to abandon their tradition and conform to mestizo laws of conduct.

Commercial Music

An international travel boom of commercialized Andean music began to develop in the 1970s and exploded in the 1990s into what locals call a "travel craze," or even a "sickness" that young indígenas have to go abroad. Numerous young indigenous musicians from the Northern Andes have taken advantage of the economic opportunities available through Western capitalism by performing commercial music and selling textiles at festivals, plazas and subways in Europe and North America. Many return to the Andes regularly, and several continue to participate in traditional music making. The ramifications of the international travel boom and the significance of commercial music can be seen in the collaboration and alliances with indígenas from other Andean countries, new forms of music, an increase in socioeconomic power, an acute self-awareness of indígenas' own cultural identity and their relationship with others, and altered dynamics between mestizos and indígenas in the Andes.

The Development of Indigenous Commercial Music and the Travel Boom

The expansion of indigenous music from primarily social and ritual music into a commodity sold to foreigners as live performance and on CDs also involves a history of mestizo-indigenous relations. According to my interviews with several urban mestizo musicians as well as Ecuadorian ethnomusicologist Juan Mullo Sandoval, mestizo musicians appropriated indigenous music for political purposes and were the first to transfer it from its original contexts to staged performances and recordings. Mestizo groups across the Andes began to borrow from indigenous folklore to create nationalistic representations in the early to mid-twentieth century. In Ecuador, the most famous mestizo group to appropriate indigenous music in the construction of a national Ecuadorian identity was Los Corazas. In the socialist Nueva Canción (new song) movement, which began in Chile and swept across Latin America during the socialist period in the 1960s and '70s, left-wing mestizo urban intellectuals and students combined protest lyrics with adopted indigenous instruments, genres, and languages in order to represent "the people" (el pueblo) in their politically oriented music. The most influential groups in the Nueva Canción movement came from Chile and Bolivia; they recorded albums that were sold across the Andes and in Europe (Carrasco 1982, Rodriguez 1988, van der Lee 2000). The first and most popular EcuadorianNueva Canción group was Jatari, formed in 1970. In an interview, Jatari's leader Patricio Mantilla explained to me that he and his colleagues began by copying Chilean songs by Violeta Parra, Victor Jara, Inti Ilumán, and Quilapayun. Jatari and other EcuadorianNueva Canción groups played indigenous instruments from the southern Andes, such as quena (vertical notched flute) and charango (small guitar-like instrument), which, according to Mantilla, had previously not been played in Ecuador. They also did field research in Ecuadorian indigenous communities and appropriated local indigenous musical instruments, genres, and language into the political songs they released on LPs and performed at protests and left-wing party meetings. Juan Espinoza, member of the Nueva Canción group Oveja Negra (Black Sheep), explained to me that "we were not trying to rescue or revive the indígenas' music -- there was no need; it was there, the indígenas were playing it. Rather, we wanted to return to their roots and then develop and progress the music in our own way for our own purpose" (my translation). When Pinochet came to power in Chile in 1973, Chilean Nueva Canción musicians who were not imprisoned, tortured, and/or killed fled to Europe where they began popularizing Andean music (van der Lee 2000) (The political situation in Ecuador was much milder). These musicians from the Southern Cone living in exile, particularly in Paris and other parts of Europe, paved the way for the subsequent popularization of Andean music by indigenous groups. According to my mestizo informants, when indígenas saw that mestizo musicians were making money by performing adopted indigenous music, indigenous musicians began recording and performing their own music outside of traditional social and ceremonial contexts (Mantilla 1996, Rodriguez 1996, Espinoza 1996, Mullo 1996). Thus, mestizo groups opened the market for and began to popularize folkloric music, helped make known the plight of the indígenas, and motivated or inspired indigenous groups to produce their own music commercially.12

At roughly the same time as socialist-inspired movements and Nueva Canción swept across Latin America, indígenas in the Valle de Imbabura began to produce textiles to be sold to international tourists. Up until 1964, indígenas were still forced to work in textile sweatshops under the huasipungo debt-peonage system. With the passage of the Agrarian Reform Act of 1964 indígenas were released from their slave-like conditions, and, though still poor and denied access to many resources, they were finally able to own and control the nature and fruits of their own labor (CEDIME 1993; Bretón 1997). Anthropologist Lynn Meisch (1997) demonstrates that, in their long history of producing textiles for Spaniards and mestizos in sweatshops, indígenas learned skills and techniques that they successfully applied to the production of textiles for tourists after they gained their freedom. Meisch also chronicles the tremendous expansion of the Saturday market at Otavalo, from the 1970s through the 1990s, into an internationally known, thriving market mobbed by foreign tourists and described in one guidebook as "the largest Indian market in South America" (Meisch 1997, Pearson and Middleton 1996). The sale of textiles to tourists at the market in Otavalo helped indígenas acquire the necessary capital for their initial trips abroad.

In the 1970s, the first Ecuadorian indigenous music groups began to travel abroad for performances, to record albums, and to commercialize their music. The first groups to record and travel abroad, such as the Peguche-based groups Ñanda Mañachi and El Conjunto Peguche, had a cultural agenda.13 They wanted to represent and teach their culture to the rest of the world. Often they would re-enact festivals or ceremonies along with the traditional local repertoire that they performed (according to interviews with members of Ñanda Mañachi and El Conjunto Peguche: Conejo 1997, Lema 1997, Pichamba 1997). Their performances included both music and dance, so although instrumentalists are men, women went along on these early trips as dancers and singers. The groups began by performing at festivals, concert halls and universities first in other Latin American countries and then in Western Europe.

These early groups paved the way for other groups, and in the 1980s the travel boom hit. Young indígenas realized that they could make much more money by selling music and textiles abroad than they could with their limited life opportunities within Ecuador. The music became increasingly commercial as groups focused more on making money and less on presenting cultural re-enactments of indigenous rituals. Indígenas traveled throughout Western Europe and North America playing music and selling textiles in streets, subways, squares, and open fairs.

In the 1990s the travel boom accelerated to a travel locura (craze), which one young traveling musician described to me as a craziness or sickness that young indígenas have to go abroad and make money.14 These young people typically traveled four to six months out of the year playing music and selling textiles. When they came home to their Andean communities they brought new perspectives and money, and had to renegotiate their lives in the Andes.15 Many young musicians spoke of the choques ("crashes," or culture shock) they went through when they returned to Peguche and Otavalo.

The internationaltravel boom and the transnational marketing of Andean music and textiles have had a tremendous impact on the indígenas' socioeconomic position, political power, ethnic and cultural identity, and music. The indígenas' Western capitalist entrepreneurship of music has led to increased economic power which, in turn, has affected intercultural relations within the Andes. Many indígenas in the Valle de Imbabura have substantially increased their individual purchasing power, allowing them not only to travel, but also to acquire stereos, Nintendos, telephones, and even cars. Yet, in some ways their standard of living has not improved, and civic infrastructure is still seriously lacking. In 1997, many families in Peguche had no running water, no garbage collection, and no sewage system. Peguche’s streets were unpaved and unnamed, cholera outbreaks were still a problem, and healthcare was poor. These extreme contrasts between the poverty prevalent in the Andes and the wealth acquired in Western capitalist nations serves to heighten indígenas' awareness of political and socioeconomic conditions. Increased economic power has enabled an increase in political power. The Confederación de Naciones Indígenas del Ecuador (CONAIE, Confederation of Indigenous Nations of Ecuador), the major activist organization for indigenous rights in Ecuador, has been gaining clout at the national level, at least partly because of the increased wealth of locals due to the international sales and travel.16

Some of my indigenous informants complained that racial tensions between indígenas and mestizos were increasing because of indígenas' newly improved economic standing and because of the popular Western romanticization and idealization of indigenous peoples. While mestizos have more social, economic, and political opportunities within Ecuador than indígenas do, indígenas have circumvented the limited life opportunities in Ecuador and found greater economic opportunities at the international level.

The following anecdote illuminates the play between indígena, mestizo, and gringo (white Westerner) racial hierarchies in the Andes. Every year the town of Otavalo has a beauty pageant. Although Otavalo is a thriving indigenous economic center surrounded by several high-profile indigenous communities, the mestizo town leadership enforced a law discriminating against indígenas and allowed only mestizo women to compete. In 1996 a scandal broke out because a young indigenous university student tried to enter the beauty competition but was refused. In the summer of 1997, the elected mestizo beauty queen of Otavalo was supposed to appear on a float in a parade celebrating a mestizo civic holiday in the town of Cotacachi. The indigenous folkloric dance troupe Saihua, which I had joined, was also to perform in this parade. Before the parade began, someone came rushing up to our dance troupe looking for a young woman in costume to fill in for the beauty queen who had failed to appear. My indigenous friends grabbed me and stuck me up on the throne on the float. The parade began, and there I was, a gringa, foreign, white, Queen of Otavalo dressed in full indigenous costume throwing out roses to crowds of mestizos and indígenas. My friends circulating amongst the crowd told me that the general reaction was one of surprise and disbelief that the Otavalo beauty queen could be a gringa dressed like an indígena. My indigenous friends from the dance troupe were delighted. Substituting a foreign white for a mestizo beauty queen was an act of resistance. To them, it was like slapping the mestizos in the face. They were showing that indigenous connections with Western cultures outranked the mestizos in the existing racial hierarchies. Many mestizos had hoped that the 1970s oil boom would be Ecuador's answer to poverty, but as it turned out the oil boom crashed and instead indígenas, who are still looked down upon by many mestizos and treated as second-class citizens, have found economic opportunity by participating in Western capitalist markets. My indigenous colleagues in the dance troupe were quick to point out how mestizos have become jealous of indígenas' newfound economic prosperity and of the relationship between indígenas and white Westerners.

Just as in many of the intercultural relations between indígenas and mestizos, the interaction between indígenas and international consumers involves layers of power dynamics. While indígenas are able to use the economic connections with foreigners to partly circumvent the socioeconomic repression they face in their mestizo-dominated country and empower themselves economically, indígenas are also subject to Western immigration laws which discriminate against poor, young individuals from the Third World. Several young musicians explained to me that when they attempt to go abroad they must undergo an arduous process of obtaining visas. Visas for the United States are particularly difficult to obtain, but more valued since playing in the U.S. is more lucrative. It is often the case that members of a musical ensemble are not all able to obtain visas at once. So instead of the whole band going, each individual will go as soon as he obtains permission. When he (and every indigenous musician I met was male) arrives in, say, Seattle or Los Angeles, he meets up with other individuals in that foreign city and they form a pickup band. Often this band might be composed of an Ecuadorian, a Peruvian, and a Colombian, for example. Because the members of these pickup bands do not share the same local musics and because their main goal in playing music is to make money, the international power dynamics manifested in the visa situation have significant ramifications for both the music and indigenous identity.

The commercial music that indígenas perform abroad and record on CDs has evolved so that it is now significantly different from the traditional music they perform at festivals and rituals in their Andean communities. The change of context has led to changes in musical structure. In a festival context, traditional music continues nonstop for hours as new songs overlap old songs in a continuous fabric of sound, but when music is performed for commercial purposes by only one ensemble and especially when it is recorded onto short tracks on CDs, it requires a more definite ending. Pepe Marcos, a young traveling musician from Peguche, explained to me that many musicians had begun adding V-I cadences to finish their songs, cadences that were previously unheard of in indigenous music.

Commercial Andean music has become pan-Andean, no longer characterized by cada llajta, the traditional uniqueness/specificity of each local community. Musicians have modified their repertoire and instrumentation in order to be able to play in pickup bands with musicians from other regions. The standard commercial instrumentation leaves behind the rich variety of local flutes and string instruments and uses all diatonic instruments, usually quena (vertical notched flute), zampoñas (mid-range pan pipes), guitars, electric bass, electronic drum kit or actual drum, and sometimes charango (small guitar-like instrument from the southern Andes). It is extremely unlikely that the musicians in a pickup band will know any of each others' local traditions. So they pool their repertoire from well-known genres and tunes such as a few popular cumbias from Colombia, huaynos from Peru, sanjuanitos from Ecuador, and even merengues and American film music. Bands also cater to foreign audiences by playing recognizable hits such as "The Lambada," "El Condor Pasa," and, for several months following the release of the film Titanic, the Titanic theme song.

Another factor aiding the trend away from specialized local repertoire towards pan-Andean repertoire is that some young people pick up musical instruments and go abroad for material gain without caring about the music or bothering to learn their region's traditions, which stimulates harsh criticism from community traditionalists. According to both indigenous musicians and music shopkeepers in Quito, this overemphasis on money is leading to a decline in the quality of the music. Many community members expressed concern that their culture is no longer being represented well to the outside world. While this is unquestionably true in some – perhaps many – cases, there are also extremely talented, knowledgeable, well-respected musicians who travel abroad, learn new repertoire, and still preserve specialized musical traditions within their home community. In other words, they have become bimusical in commercial and traditional Andean music styles.

Just as commercial Andean music has developed from locally specific styles into a pan-Andean musical style, indigenous identity has been shifting from highly localized community identities to a larger-scale regional pan-Andean indigenous identity. Musicians who perform music from other regions and work closely with indigenous musicians from other countries have come to identify with one another's music and cultures. The formation of larger regional indigenous identities has given indígenas more strength in their political movements. There exist newly formed political coalitions in the form of umbrella groups of several indigenous peoples fighting for indigenous rights (an example is the CONAIE, the Confederación de Naciones Indígenas del Ecuador, or Confederation of Indigenous Nations of Ecuador). Some young musicians even told me that they identified strongly with Native Americans from the United States whom they had met while playing abroad at festivals; North American Native music scholar Tara Browner has observed this trend in pan-Indian identities spanning the Americas at powwows in the U.S. (personal communication, 2000). The most extreme case of pan-indigenismo stretching across the Americas, that I have seen, was a group of Mexicans dressed in the style of Hollywood representations of US Native Americans (complete with long feather headdresses, beaded breastplates, and fringed leather outfits) playing southern Andean wind instruments and synthesizers in a street market in northern Europe in the summer of 2004. Although they were probably much more concerned with material gain than representing cultural identities, their casual combination of elements from indigenous/native cultures across the Americas reveals that they associate these different cultures with one another, and indeed probably take these pan-indigenous associations for granted.

Not all indígenas participate directly in the international travel boom and transnational capitalism. Not all indígenas travel, and not all indígenas have benefited economically from recent transnational trends (as is the nature of capitalism). However, in the community of Peguche near Otavalo all of the indígenas whom I met had either traveled abroad themselves, or had male relatives or immediate family members who did, or manufactured textiles sold to foreigners. The main industry of Peguche is textiles, which sell well on the international market. The majority of traveling musicians also work in (or collaborate with family members who work in) cottage-industry textile production and distribution. Indígenas whose primary livelihood is agriculture are still quite poor, particularly those living in the highest and most remote mountain communities. Indígenas from other regions consider Otavaleños to be very lucky for their easy access to international tourism, for their international travels, and for their economic success.

Personal Creative Music

I have discussed how indígenas use traditional music and commercial music to mediate their interactions with mestizo culture and with Western capitalist conglomerate culture. Now I will address a third type of music: personal creative music.17 Personal creative music comprises fusions and intercultural collaborations with the diverse musical cultures indígenas encounter in their daily lives. While traditional music and commercial music are categories used by indígenas themselves, I heard very little discourse about this third type of music, with the exception of some traditionalists who disapproved of it and the individual musicians who gave me their recordings. But I felt that it was significantly different, both musically and in its cultural role, from traditional and commercial music and merited its own category.

While traditional music is heard often in the Andes and commercial music is heard often abroad, the personal creative category of music is simply not heard very often outside of private contexts. The heightened concern within Andean communities over preserving indigenous culture translates into heavy community scrutiny and negative reception of nontraditional music by many traditionalists. Experimental fusions of Andean folk music with that of Jimi Hendrix, reggae, or classical cello, for example, are not big moneymakers on the international market. I discovered this type of music primarily through copies of personal recordings and pirated cassettes that were given to me by musicians themselves.

In this heterogeneous category of musicmaking, musicians typically draw upon instruments, genres, and stylistic elements from a wide variety of Western and world music while retaining identifiably Andean indigenous musical qualities. For example, the well-known group Ñanda Mañachi, which is highly respected in Peguche for its traditional music performances, has recorded a not-so-readily-available album called Ecuatoriales - El Viaje Del Yahe in which they collaborate with the Afro-Ecuadorian ensemble Juyungo to play fusions of traditional Andean music and Afro-Ecuadorian Marimba music as well as other styles. Another traveling musician, Javier Grijalva, has given me home-made recordings of collaborations and jam sessions he has had with French and American musicians in his travels. He explained to me that traveling abroad provides him with the freedom for musical exploration and expression that he does not have in Ecuador. The Peguche-based groups Jailli and Winiaypa combine panpipes and electric guitars and/or basses together with lyrics that address the contemporary issues of indígenas who travel back and forth from the Andes to other continents. Other examples include fusions of Andean music with rock, rap, reggae, Afro-Ecuadorian music, and New Age, as well as cover versions of Beatles pieces, church hymns, and classical music. In many of these examples, Andean instruments, particularly bamboo panpipes and flutes, and lyrics speaking of contemporary travel or historic struggles for human rights by indígenas, serve as musical indigenous identity markers.

The following excerpt of lyrics is from the song "Daqui Lema" on the CD Gotitas del Amor by Winiaypa, a group of young indigenous musicians from Peguche. The liner notes to this album contain the following dedication: "We dedicate this work to the entire indigenous community of America, especially to the Imbaburan community that travels the world over, and similarly a special mention to the Otavalon community in Belgium and the rest of Europe" (my translation). The politically charged lyrics tell of a local hero who was executed for leading an indigenous uprising in the nineteenth century, and proclaim that the people are united and ready for a "new battle." These locally specific lyrics are set to a solid reggae musical background played on electric guitar, electric bass, and drum set, and accentuated with mournful passages on (non-local) Southern Andean panpipes and electric guitar solos.

DAQUI LEMA

(text and music by Segundo Gramal, member of Winiaypa, translation mine)REFRAIN

Son las cuatro

del día lunes 18 de diciembre

del año 1871, se escucharon sí

los gritos fuertes de nuestro levantamiento

que gritaban daqui, daqui, daqui, daqui…

FINAL VERSE

Lo mataron sin justicia

porque reclamó libertad

De la pacha mama salía

su energía liberadora

¿Por qué ellos pelearon, por qué?

¿Para qué seguiremos peleando?

Si la pacha mama es nuestra

y por ella todos viviremos

aquí estamos todos juntos

listos pa la nueva batallaREFRAIN

It's four o'clock

on Monday December 18th

of the year 1871, yes they heard

our uprising’s hard screams

that cried Daqui, Daqui, Daqui, Daqui…

FINAL VERSE

They killed him without justice

because he reclaimed freedom

From Mother Earth came

his liberating energy

Why did they fight, why?

For what do we continue fighting?

If Mother Earth is ours

and thanks to her we all live

here we are all together

ready for the new battle

The only public performance of such creative fusions that I witnessed during my stay in the community received disapproval from community traditionalists. The folkloric dance troupe Saihua, which consists primarily of indígenas in their teens and twenties, chose to choreograph two pieces to music by the two local bands Jailli and Winiaypa. Both of these pieces were played on electric guitars and bass, and, particularly the song by Jailli, showed the influence of American rock. The lyrics, part in Spanish and part in Quichua, describe the culture shock that young indígenas experience as they travel across "mountains and oceans." The dance steps, though stylized and prepared for stage presentation at civic events, were based on traditional dances from the surrounding region. Though their dancing was praised, their choice of such nontraditional music was criticized.

The musicians who create these types of creative and eclectic personal music also perform traditional festival music at home and sell commercial music abroad. Transnational commercialization provides previously unavailable spaces abroad and in recording studios that allow musicians the freedom from community scrutiny to perform this music. These creative fusions and collaborations are an outlet for individual musicians to express their personal experiences regarding their intensively transnational lifestyle. While traditional music is an important part of their cultural heritage and commercial music is economically important, I argue that these creative personal expressions are the most reflective of the indígenas' contemporary transnational reality and help them to cope personally and artistically with the world in which they live.

Conclusions

“What would happen, I began to ask, if travel were untethered, seen as a complex and pervasive spectrum of human experiences? Practices of displacement might emerge as constitutive of cultural meanings rather than as their simple transfer or extension... Virtually everywhere one looks, the processes of human movement and encounter are long-established and complex. Cultural centers, discrete regions and territories, do not exist prior to contact, but are sustained through them... Intercultural connection is, and has long been, the norm... Cultural action, the making and remaking of identities, takes place in the contact zones, along the policed and transgressive intercultural frontiers of nations, peoples, locales.” (Clifford 1997:3-7)

The Valle de Imbabura is such a contact zone. From the present day stretching back to at least the 1400s, intercultural contacts and relationships have influenced, defined, and redefined the culture, identity, worldview, and socioeconomic position of the indígenas from Peguche. In this paper, I focused on three different types of music (traditional festival music, commercial music, and personal creative music) that are performed by indigenous musicians from Peguche, and I showed how intercultural relations influenced the development of these musics and how the music in turn has impacted contemporary intercultural dynamics, hierarchies, and identities.

Historical interaction and struggles between Spanish colonists and missionaries and indígenas, which have largely shaped the social structure and identity politics between mestizos and indígenas today, are manifested in what is called indigenous "traditional music" in the form of musical syncretisms and the music's association with syncretic religious beliefs. Traditional indigenous music plays a role in contemporary indigenous-mestizo relations as an identity marker distinguishing two different ethnic groups that are no longer distinguishable by phenotype, as a positive representation of indigenous culture and source of pride fighting the negative stereotypes and stigma associated with being "Indian," and as a source of conflict and resistance when mestizo authorities want indígenas to cease practicing certain rituals (as in the case of tinku).

Indigenous-mestizo relations influenced the development of the travel boom and the commercialization of indigenous music in several ways. The mestizo Nueva Canción movement popularized folkloric (appropriated indigenous) music, opened up international markets, and inspired indígenas to commercially produce their own music. The indígenas' generations of experience making textiles in sweatshops gave them the skills to successfully make textiles for an international market, and Ecuador's Agrarian Reform Act ended their slave-like bonds and gave them the freedom to become capitalist entrepreneurs. The successful commercialization of indigenous music and the travel boom had a strong impact at home: many indígenas had more money, more power, and a greater awareness of the social and political situation in Ecuador and in their community, all of which influenced the dynamics in their interactions with mestizos. The racial hierarchy in the Valle de Imbabura from top to bottom is white/gringo, mestizo, indígena. Indigenous alliances with white foreigners have disrupted the social hierarchy. At the same time, the harsh immigration policies of wealthy western countries have led to the phenomenon of transnational pickup bands, which in turn has led to the development of a pan-Andean commercial musical style and pan-indigenous identities. Pan-indigenous alliances have also led to increased political clout at the national level.

Finally, personal creative fusions are a way for indigenous musicians to personally express and cope with the impact on their lives of international travel, myriad intercultural relations at home and abroad, and interethnic stratification and struggles at home. The fusions reflect their cosmopolitism and participation in the commercial world music scene, their alliances with foreign musicians and non-Ecuadorian indigenous cultures, and their strong local indigenous identity and pride. This category of music is relegated to private spaces at home, in studios and abroad, spaces where it is beyond the hearing range of community members, especially those who are concerned that their heritage and identity be maintained and well represented through traditional indigenous music.

Each type of music serves a different purpose in this cosmopolitan Highland community. Traditional music is a tool in the identity politics struggle at home, commercial music is an economic tool used abroad for circumventing the socioeconomic oppression at home, and creative music is a tool for personal expression and coping at the individual level. Combined, all of these musical experiences have changed indígenas' political and socioeconomic status, world perspectives, self-identity, life opportunities, and relationships with other cultures.

1. The community of San José de Peguche, officially named Dr. Miguel Egas, is known colloquially as Peguche.

2. I prefer to use the term "intercultural" instead of "transnational" or “international,” because I feel that it reflects the greater importance of cultural and ethnic identity as a marker of difference over nationality, and because it allows me to refer to interactions amongst different cultures at local, regional, national, and transnational levels. I choose to use “intercultural” instead of “interethnic” because, in this region, ethnicity is largely constructed through cultural markers. (Note that I am using the term "intercultural" in a much broader sense than Mark Slobin [1993]).

3. Traditional music and commercial music are terms used by Andean musicians. Personal creative music is my own term for a third style of Andean music that has not gained community acceptance but which I felt warranted its own category in a discussion of indigenous music from this region.

4. There are no accurate statistics on ethnicity in Ecuador; the national census has not included ethnicity, and the boundaries of ethnicity in this region are very subjective. The Abya-Yala Cultural Center, an important press for indigenous publications in Ecuador, estimates Ecuador's indigenous population to be just over 3.1 million, out of a total population of roughly 12.8 million, though I have seen estimates as high as 60%.

5. See Schechter (1982:823-854) for an explanation of Quechua A (what locals call Quichua) and Quechua B.

6. Mestizo and indigenous identity vary considerably amongst different regions of the Andes. For example, Raul Romero (1990:3-6) explains that in the Mantaro Valley in Peru mestizos integrate and acknowledge their indigenous and Western heritages. These mestizos are bilingual in Quechua and Spanish and are active in the Western capitalist market while maintaining their cultural traditions. Many of the characteristics that are used to describe mestizos in this Peruvian valley also apply to indígenas in the Ecuadorian Imbabura Valley. The main difference is how these groups of people identify themselves and are identified by others.

7. My mentor, Ecuadorian ethnomusicologist Juan Mullo Sandoval, made this assertion (personal communication, 1996), and I believe that the gaita duets' repetitive and cyclical structure, nondiatonic intonation, performance practices, and associations with pre-Columbian beliefs support his claim.

8. I chose this photo for its clarity of the instruments being played. Unfortunately, the majority of my photos of gaita duets taken during the festivals are obscured by dancers who, by tradition, dance in a tight circle around the musicians.

9. An example of how this myth of racial purity is perpetuated can be seen in the legends that explain why some children are born with lighter colored skin, hair, and/or eyes. My indigenous host mother warned me not to go up into the mountain by myself without protection against the spirit of the mountain (i.e. wearing red bead bracelets and red waistband, and carrying whiskey and tobacco offerings), for there were instances in which young women had been kidnapped by the mountain spirit and returned three months later pregnant, eventually giving birth to a light-haired, light-skinned child. These children were deemed not to be of mixed ethnicity (born of an indigenous mother raped by a Spanish landholder), but rather children of the mountain spirit.

10. "Tinku es el nombre de las peleas rituales en las que se encuentran dos bandos opuestos…. Parece un combate guerrero, pero en realidad se trata de un rito; por eso une. El tinku es la ‘zona de encuentro’ donde se juntan dos elementos que preceden de dos direcciones diferentes…. Mediante la pelea [tinku] lo que se pretende establecer es un intercambio de fuerzas necesario al equilibrio social…. El juntarse en combate es una ‘igualación’" (Harris and Bouysse-Cassagne 1988:241-242). “Tinku es también, y hasta nuestras días, el nombre de las batallas rituales que occurren, sea al interior de una gran comunidad entre los distintos grupos que componen la estructura social…, sea entre comunidades, unas contras otras…. estos sangrientos combates ceremoniales… llegan incluso a la muerte…. El ajuste es necesario, sin embargo, precisamente ahí donde hay una ‘enemistad,’ una diferencia, y los golpes de los tinku no hacen otra cosa que crear la concordia…. La normación estricta de las armas y la manera de enfrentarse, el día fijo y más aún la limitación precisa de las horas en que comienzan y terminan, sitúan a los tinkus concretamente junto a los ritos” (Cereceda 1998:342).

11. Mestizos who live in the town of Cotacachi, with the exception of the policemen, stay out of the way in their houses during this festival. I spoke with one such mestizo woman who invited me into her house to wash the tear gas from my face.

12. Note that this is based on a historical account provided by urban mestizo musicians and scholars. Most indigenous musicians with whom I spoke did not tend to acknowledge the role of mestizos in the formation of indigenous performance groups. However, two indigenous political activists who are producers/managers of different indigenous folkloric groups confirmed the account given by mestizos. I have not encountered any published material that addresses this.

13. Members of both of these groups were my informants. My host parents had actually met while performing with El Conjunto Peguche, and I took music lessons with and attended several gigs by Ñanda Mañachi.

14. Many North American scholars have asked me how indígenas are able to finance their initial trip abroad. The money earned from successfully marketing textiles to international tourists/consumers at the market in Otavalo and at international distribution centers made possible through connections made in Otavalo, combined with financial help from family and friends, provides the means for indígenas to begin traveling abroad. Also, according to Meisch (1997), agencies now exist in Otavalo that will loan indígenas the money for plane fare.

15. There are of course also some who do not return and choose to remain abroad. However, numerous traveling individuals do return regularly to their Andean communities, enough to have a significant impact upon the community.

16. See Las Nacionalidades Indígenas en el Ecuador: Nuestro Proceso Organizativo (1988) for information on the history and goals of the CONAIE (Confederación de Naciones Indígenas del Ecuador) and the smaller regional organizations that it united when it was formed in 1986.

17. I have grappled with what to call this music (the only musical category not given a name by indigenous musicians themselves). Still unsatisfied, I have settled on "personal creative music." By no means is it my intent to imply that traditional and commercial music are neither personal nor creative. Rather, I aim to emphasize that personal creative music is performed in private spaces for personal (as opposed to communal, ritual, or economic) motivations and that, in creating it, musicians have complete creative freedom, free from the demands of their community and the international market.

Bretón, Víctor. 1997. Capitalismo, reforma agraria y organización comunal en los Andes: una introducción al caso Ecuatoriano. Lleida, Spain: Ediciones de la Universitat de Lleida.

Buitrón, Anibal and Collier, John. 2001 [1971]. El valle del amanecer. Otavalo, Ecuador: Instituto Otavaleño de Antropología.

Burkholder, Mark and Johnson, Lyman.1994. Colonial Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carrasco, Eduardo. 1982. La Nueva Canción en América Latina. Santiago, Chile: Centro de Indagación y Expresión Cultural y Artística (CENECA).

Centro de Investigación de los Movimientos Sociales del Ecuador (CEDIME). 1993. Sismo Etnico en el Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador: Ediciones Abya-Yala.

Cereceda, Veronica. 1988. “Aproximaciones a una estética andina: de la Belleza al Tinku." In Raíces de América: el mundo Aymara, edited by Xavier Albó, 283-356. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, Sociedad Quinto Centenario.

Clifford, James. 1997. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Conejo, Segundo. 1996. Interview with the author. Peguche, Ecuador.

__________. 1997. Personal Communication. Peguche, Ecuador.

Espinoza, Juan. 1996. Interview with the author. Quito, Ecuador.

Grijalva, Javier. 1996. Interview with the author. Quito, Ecuador.

__________. 1997. Personal Communication. Cayambe, Ecuador.

Harris, Olivia and Bouysse-Cassagne, Therese. 1988. “Pacha: en torno al pensamiento Aymara." In Raíces de América: el mundo Aymara, edited by Xavier Albó, 217-281. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, Sociedad Quinto Centenario.

Juyungo with Ñanda Mañachi. 1996. Ecuatoriales - El Viaje Del Yahe. Ecuador. CD.

Lema, Emna. 1997. Personal Communication. Peguche, Ecuador.

Mantillo, Patricio. 1996. Interview with the author. Quito, Ecuador.

Marcos, Pepe. 1997. Personal Communication. Peguche, Ecuador.

Meisch, Lynn. 1997. “Traditional Communities, Transnational Lives: Coping with Globalization in Otavalo, Ecuador.” Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University.

Mendoza, Zoila. 2000. Shaping Society through Dance: Ritual Performance in the Peruvian Andes. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press.

Miles, Elisabeth J. and Chuse, Loren. 2000. "Spain." In Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Vol. 8, Europe, edited by Timothy Rice, James Porter and Chris Goertzen, 588-603. New York: Garland Publishing.

Moreno, Segundo Luis. 1972. Historia de la música en el Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador: Editorial Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana.

Mullo Sandoval, Juan. 1996. Interview with the author. Quito, Ecuador.

__________. 1997. Personal Communication. Quito, Ecuador.

Muratorio, Blanca. 1994. "Discursos y silencios sobre el indio en la conciencia nacional." In Imágenes e imagineros, edited by Blanca Muratorio, 9-21. Quito, Ecuador: FLACSO-Sede Ecuador.

Las nacionalidades indígenas en el Ecuador: nuestro proceso organizativo. 1988. Ecuador: TINKUI-CONAIE.

Pearson, David and Middleton, David. 1996. The New Key to Ecuador and the Galapagos. Berkeley, CA: Ulysses Press.

Pichamba, Luis. 1997. Personal Communication. Peguche, Ecuador.

Platt, Tristan. 1988. “Pensamiento político Aymara." In Raíces de América: el mundo Aymara, edited by Xavier Albó, 365-450. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, Sociedad Quinto Centenario.

Quimbo, José Manuel. 1996. Interview with the author. Peguche, Ecuador.

Quinche Lema, Paola. 1997. Personal Communication. Peguche, Ecuador.

Rodríguez, Marcelo. 1996. Interview with the author. Quito, Ecuador.

Rodríguez Musso, Osvaldo. 1988. La Nueva Canción Chilena: continuidad y reflejo. Havana, Cuba: Casa de Las Américas.

Romero, Raul. 1990. "Musical Change and Cultural Resistance in the Central Andes of Peru." Latin American Music Review 11(1):2-33.

Schechter, John. 1982. "Music in a Northern Ecuadorian Highland Locus Microform: Diatonic Harp, Genres, Harpists, and Their Ritual Junction in the Quechua Child's Wake." Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Texas at Austin.

__________. 1992. The Indispensable Harp: Historical Development, Modern Roles, Configurations, and Performance Practices in Ecuador and Latin America. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press.

__________. 1996. "Latin America/Ecuador." In Worlds of Music: An Introduction to the Music of the World's Peoples, Third Edition, edited by Jeff Todd Titan, 428-494. New York: Schirmer Books.

__________. 2000. "Ecuador." In Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Vol. 2. South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, edited by Dale A. Olsen and Daniel E. Sheehy, 413-433. New York: Garland Publishing.

Slobin, Mark. 1992. "Micromusics of the West: a Comparative Approach.” Ethnomusicology 36 (1):1-87.

Spalding, Karen. 1984. Huarochiri: An Andean Society under Inca and Spanish Rule. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Stark, Louisa R. 1981. “Folk Models of Stratification and Ethnicity in the Highlands of Northern Ecuador.” In Cultural Transformations and Ethnicity in Modern Ecuador, edited by Norman E. Whitten, Jr., 387-401. Urbana: University of Illinois press.

Turino, Thomas. 1993. Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press.

van der Lee, Pedro. 2000. Andean Music from Incas to Western Popular Music. (Incomplete Doctoral Dissertation text published posthumously). Sweden: Department of Musicology, Göteborg University.

Winiaypa. n.d. Gotitas del Amor. Tune CD860101. CD.

World Bank. 2003. World Development Indicators Database. http://www.worldbank.org/data/dataquery.html (accessed May 6, 2004).