Of Their Knowledge in Musick: Early European Musical Encounters in Egypt and the Levant as Read within the Emerging British Public Sphere, 1687-1811

Biography

Ben Harbert is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Los Angeles and received a Bachelor of Arts in music and anthropology from Wesleyan University. He has examined topics including Egyptian extreme metal, American prison music, 17th century musical exploration in the Near East, the Spanish nationalist avant garde, and mathematic principles of Indian rhythms. In 1997, Harbert was awarded the Thomas J. Watson Fellowship for a yearlong study in Egypt, India, and Spain. At Chicago's Old Town School of Folk Music, he developed and directed a comprehensive world music department and acted on the education committee for the Chicago World Music Festival. He has guest-lectured on music internationally including the International Council of Traditional Music, Society for Ethnomusicology, International Association for the Study of Popular Music, American Folklore Society, Kent State University, and University of New Haven. He is currently an Artist in Residence at the Los Angeles Music Center as an American Music specialist and writing his Ph.D. dissertation on music in Louisiana and California prisons at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Abstract

The encyclopedic urge of the Orientalist movement and the insatiable appetite for travel literature produced a myriad of documents describing the customs of the Arab people during Britain’s colonization of Egypt and the Levant. As British taste for the exotic grew, travel accounts flooded England. Documents that depicted early musical encounters are of particular interest to ethnomusicologists. Thanks to a lingering British passion for books and old colonial testimonials, a reservoir of colonialist literature survives. We must, however, understand these musical descriptions from the perspective of the European authors. Examination of this body of work will comment on both the history of music in Egypt and the Levant and the Enlightenment bourgeoisie travelers. In this article, I critically examine a body of travel literature written between 1687 and 1811 that directly addresses Egypt and the Levant. The points of inquiry for this analysis are: First, how does musical depiction fit into an overall early British Enlightenment worldview? Second, why was music of particular interest to 18th and 19th century Europeans? Third, how did this literature inspire readers in the emerging British public sphere?

In a post-colonial academic world, much historical ethnomusicology examines peak moments of colonial power. After reading 19th century accounts of John Lewis Burckhardt, Richard Burton, and Lady Anne Blunt, I became curious about British traveler impressions of Arab music before Napoleon’s 1798 campaign of Egypt, before notions of social Darwinism, and before Orientalism became an acknowledged scientific discipline.

There has been good critical attention on early cross-cultural musical impressions of the European musical gaze (Racy 1996; Locke 1998). These critiques present 19th century travelogues as Romantic representations that essentialized and idealized indigenous ways of life. The emerging mercantile class produced and consumed travelogues that performed the double work of fantastical verisimilitude and of indirect ideological support of European imperialism. Through one-sided descriptions of the timeless Oriental, the European colonialist inscribed the power relations of political and economic dominance.

Notwithstanding the trenchant literary criticism of 19th century travelogues, the ideological and political backdrop of 17th and 18th century Britain draws our attention to a leisurely political ascension of the bourgeoisie, an ascension born in nascent intellectual circles. The intellectual climate in which 17th and 18th century travelers collected data, in which their publishers published travelogues, and in which a nascent bourgeoisie society read and discussed the content was markedly different from 19th century travelogues. While they share common themes with 19th century travelogues, earlier travelogues were more idiosyncratic and less defined as a genre.

The British Enlightenment was a period of optimistic moral reform initiated by a mercantile class that was gaining self-awareness as it rose to economic and political dominance. The point of articulation for this rise to power was a multifaceted conversation that encompassed political, social, aesthetic, and scientific thought that had turned public through intellectual societies, coffee-houses, travelogues and periodicals. This paper looks to these points of articulation to see how commentary on Arab music informed the nascent self-image of the ascending British bourgeoisie. I argue that through travelogues, travelers were able to dramatize their search for self-understanding by means of their descriptions and evaluations of musical encounters. In its political-intellectual context, the ways in which these dramatic encounters were written operated in conjunction with the larger process of constituting the British Enlightenment with examples of moral idealism embodied through the musical performance of manners and of rational idealism reified in musical forms.

Plenty of general histories of the early period British Enlightenment exist (Campbell 1988; Dolan 2000; Frantz 1934; Kamps and Singh 2001; Sattin 2000; Searight and Wagstaff 2001; Wolff 2003), but none look specifically at musical impressions in travelogues from the Levant. During travels to London in the summer of 2005, I examined primary sources of early musical encounters.1 I scoured archives, libraries, and rare bookstores for early English language accounts of the music of Egypt and the Levant.2 What is interesting about musical commentary is that music, for the gentleman of the British Enlightenment, straddled science and morality. Music had multifaceted discursive power—it was at once an expression of scientific justness and mannered decorum. In this paper, I will connect Enlightenment conceptions of music to traveler’s descriptions of music and provide an overview of musical descriptions in these Enlightenment travelogues. These connections will show how the travelogues were complicit in bourgeois self-definition under the guise of rational assessments of taste and discovery. Before connecting musical scientism in these travelogues to the emerging universal rationalism of bourgeoisie political discourse, I will provide a description of the context of musical critique at home in Britain.

The Science of Moral Conduct: Musical Description in the Literary Climate of the British Enlightenment

In the British Enlightenment, musical critique was part of a general emergence of criticism in the public sphere. As Jürgen Habermas describes it, the public sphere was an imaginary space suspended between state and civil society. It was a constellation of social institutions clubs, journals, coffee houses, societies, and periodicals in which private individuals assembled for the free, equal interchange of reasonable discourse (Habermas 1991). Critical reflection became the cornerstone of a new genre of public debate, attempting to convince, inviting contradiction. As Peter Hohendahl argues, early practices of criticism were inextricably tied to the political facets of the public sphere. In the eyes of the mercantile class, discourse in the public sphere was founded upon a polite, informed public opinion pit against the dictates of autocracy (Hohendahl 1982:52-53). We have record of this public opinion in the pages of Joeseph Addison’s Spectator and Sir Richard Steele’s Tatler periodicals. These dailies were the literary fuel for British criticism in the early 18th century. In the Tatler, Steele set his sights on “gentleman” who were “public-spirited” but had little perspective on their social and intellectual lives. As stated in his first issue, the daily was aimed at “gentlemen, for the most part being persons of strong zeal, and weak intellects, it is both a charitable and necessary work to offer something, whereby such worthy and well-affected members of the commonwealth may be instructed, after their reading, what to think” (Steele, Addison, and Chalmers 1822 [1709]:2-3). Two years after Steele’s offer to the British gentleman, Addison refined the daily agenda as a medium for Enlightenment project. The Spectator’s stated aims were to “to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality … [for readers to] find their account in the speculation of the day … [to bring] philosophy out of the closets and libraries, schools and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea-tables and coffeehouses” (Addison and Steele 1889 [1711]:103). Though these aims claimed to do apolitical rational work, political themes of the British public sphere emerge: moral correction and satiric ridicule of a profligate, socially degenerate aristocracy, class unification, and, most importantly for the purposes of this paper, the development of norms and practices that could govern relationships between the bourgeoisie and its social superiors.

These periodicals were part of the birth of a general practice of criticism in the British Enlightenment, a struggle that used notions of a universal rationalism to debate the terms of the bourgeoisie’s rise to prominence. Clubs, societies, and coffee houses became public spaces in which, among many other things, music and travelogues were fodder for rational polemics. It is in this context that travelogue “science” and reporting developed with respect to music criticism.

In a 1711 edition of the Spectator, Addison argued that critical laws of music were deduced “from the general sense and taste of mankind, and not from the principle of those arts themselves. … Music is not designed to please the chromatic ears, but all that are capable of distinguishing harsh from agreeable notes” (Addison and Steele 1889 [1711]:151). In other words, music has universal principles that are empirically discernable. Addison rules out the possibility of music detached from science, he denies that a musical system might have its own native principles.

Music reviews in places like the Spectator formed part of public discourse. Critical concertgoers discussed music in concert lobbies, formalized their ideas by writing in periodicals, and debated the merits of these ideas in coffee houses. British critics were not musicians, but rather, “gentlemen” or bourgeois connoisseurs. By and large, music criticism was a rational defense of musical taste, and 18th century criteria for musical taste, according to literary historian Harold Love (2004) and music historian Herbert Schueller (1952), fell into two areas: music as a product of scientific justness and music as an emotional expression.

Overview of Musical Descriptions in Enlightenment Travelogues

In the preface to Travels through Turkey in Asia, the Holy Land, Arabia, Egypt, And other Parts of the World, traveler Charles Thompson best put the benefits of travel: “we consider that Travelling, in its own Nature, tends to wean us from our Prejudices, to polish our Manners, to improve our Judgment, to refine our Taste, and to furnish us with every Kind of useful Knowledge” (1754:A2). Traveling was critical to the Enlightenment project for it offered a wider perspective of the rational world. If one could not manage the travel, the travelogue provided a virtual experience. The ability of the travelogue to stand in for worldly experience often relied on engaging personal stories of adventure in which the narrator’s data collection was rife with danger and drama.

Many early European explorers funded their years of travels with inheritance or secured patronage. Before embarking, many studied science, drawing, and history so they might absorb and document knowledge of the world more effectively. Explorers had a number of reasons for exploring; for example, some were inspired by Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopedia (1751), some by the pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and some by finding the source of the Nile. Most travelers stayed abroad for years and covered vast territory. Given their varied agendas, this diverse group of explorers produced volumes of data. This paper examines work published between 1687 and 1811, in styles ranging from dry reportage to first-person testimony.

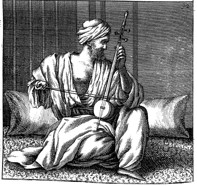

Plates 1 and 2. A Jew and a Moor from Corneille le Bruyn’s Voyage to the Levant (1702) with representative instruments (158, 192).

While these travelers were certainly committed and attentive, their methods were makeshift and idiosyncratic—especially when it came to describing music. In a cosmopolitan land of Arabs, Turks, Moors, Muslims, Christians, and Jews, travelogue commentary on music ranged from offhand observations to full chapters on the music of the natives. In the former category, consider the above plates of a Jew and a Moor from Corneille le Bruyn’s Voyage to the Levant. Of the first plate, le Bruyn writes:

I have so represented it, that I might at one and the same time shew what sort of Instruments they make use upon times of Rejoycing. This has only three Strings, and is play’d upon with a Bow just as a Violin. The Body of the Instrument is on Ebony, and the Skrews with which they stretch the Strings are of Ivory, and the Sound is tolerable.” (1702:157)

This mix of empirical organological information and social context punctuated by a lackluster judgment of taste illustrates the lack of methodical observation.

Far from being eccentric marginal literature, travelogues were among the most frequently read books in Enlightenment Britain, inextricably linked to an increasing consciousness of history, geography, and the human condition. Taken as a whole, an examination of musical commentary in these travelogues reveals the following wide-ranging topical categories: entertainment in the company of a local dignitary (Bruce 1790; D’ Arvieux 1732; Denon 1803; Niebuhr 1792; Pitton de Tournefort 1718; Rooke 1783; Savary 1786; Thèvenot 1687; Walsh 1803), at a Cairo festival for cutting the banks of the Nile (Montagu and Cooke 1799; Niebuhr 1792; Parsons and Berjew 1808; Savary 1786; Thompson 1754), at weddings (Bruce 1790; D’ Arvieux 1732; Niebuhr 1792; Savary 1786; Thèvenot 1687; Van Egmont and Heyman 1759), women’s music of harems (Clarke 1810; D’ Arvieux 1732; Denon 1803; Hasselquist 1766; Niebuhr 1792; Savary 1786), music performed by hired women for lamenting the dead (Bruce 1790; Clarke 1810; Savary 1786), entertainment in coffee houses (Griffiths 1805; Niebuhr 1792; Thèvenot 1687), Sufi rituals (D’ Arvieux 1732; Niebuhr 1792; Thèvenot 1687), music for the Cairo caravan to Mecca for the hajj (Bruyn 1702; Chateaubriand 1811; Denon 1803; Hasselquist 1766; Parsons and Berjew 1808; Pitton de Tournefort 1718),Turkish military music (D’ Arvieux 1732; Denon 1803; Niebuhr 1792; Ray 1693; Thèvenot 1687; Walsh 1803), and music for healing (Niebuhr 1792; Shaw 1757; Thompson 1754). The travelers also observed music as demonstrating the relative knowledge of arts & sciences (Bruce 1790; Niebuhr 1792; Ray 1693; Shaw 1757; Volney 1787).

In learned societies, clubs, and coffee houses, these British and translated non-British travelogues informed a general critical debate about subjects such as science, geography, politics, technology, and even ornithology. Explicitly, travelogues fueled the empirical project. Implicitly, travelogues fueled the political assertions and social consolidation of the bourgeoisie mercantile class through the emerging practice of criticism. Enlightenment discourse had a major role in constructing new European, British, and bourgeois world-views. An example of this may be found in the preface of French linguist and historian Claude Savary’s travelogue. Savary poetically argues that the pursuit of a European consciousness lies in rational liberation:

But after examining with deliberate attention, the manners and the genius of different people, after calculating the precise influence of education, laws, and climate, on their natural and moral qualities, [the traveler] will extend a sphere of his ideas, reflexion will throw off the yoke of prejudice, and break the bonds with which custom has enchained his reason. It is then that, looking towards his own country, the bandage will drop from his eyes, the erroneous opinions he has there formed will vanish, and every thing will bear a different aspect. (1786:vi)

Many Enlightenment travelogues prefaces dramatized the pursuit of knowledge. Arguably, the explorer as a first-person character of his travelogue provided a dramatic enactment of education itself. Travelers descended into strange lands to conjecture from the observable signs of the familiar and the unfamiliar, all the while dramatically negotiating dangerous obstacles. As Dutch explorer Ægidius Van Egmont says in his preface, “[Travelers] have disregarded fatigue and expence; nay even hazarded their lives in order to improve their minds, and make discoveries that might prove advantageous to their country” (1759:v-vi). These were the literary martyrs of the Enlightenment. Their accounts fed the growing discourse of rational criticism developing back in Britain.

The Scientific Justness of Music

In 1711, the English philosopher Shaftesbury stated, “Harmony is harmony by nature, let particular errors be ever so bad, or let men judge ever so ill on music” (Shaftesbury in Dupré 2004:121). Music was organic and universal; its natural laws were recapitulated in all parts of life: national, civic, domestic, and political. In 1749, D’Alembert championed the work of Rameau for finding a rational, scientific basis for harmony in the harmonic series. He wrote, “Harmony, previously guided by arbitrary laws, has become through the efforts of M. Rameau a more geometric science, and one to which the principles of mathematics can be applied with a usefulness more real and sensible than had been until now” (D’Alembert in Christensen 2004:11). A year later D’Alembert claimed that, “Thanks to the labors of a manly, courageous, and fruitful genius, foreigners who could not bear our “symphonies” are beginning to enjoy them” (Alembert, Schwab, and Rex 1995:100) D’Alembert goes on to compare Rameau’s science of harmonics with Newton’s laws of gravity.

Most travelogues dismiss the possibility of Arab music having a scientific justness. This is evident in entire chapters devoted to native music in which the travelers’ voice bafflement over the absence of the native science of music. English naturalist John Ray presents this as a deficiency: “in Liberal Arts and Sciences, such as we teach in our Countries, they are not Instructed, for they have not only one of these Learned Men, but esteem learning of these Sciences a Superfluity, and loss of Time” (1693:182). Ray understands the apparent lack of musical science as relative difference in cultural priorities.

On the other hand, Scottish traveler James Bruce recounts meeting musicians who amazed him with melodies that he thought near perfection. He took the effort to learn the music on what he describes as the “guitar, the wretched instrument of that country” (1790:51). Out of curiosity, he asked questions about the music. In his own words: “I had frequent interviews with these musicians in the evening; … and, from every possible inquiry, I found every thing, allied to counterpoint, was unknown among them” (1790:51). By science and harmony, travelers like Bruce suggest that the natives had no systematic mathematical principle of harmony and overtones.

Thomas Shaw describes the problem as one of unfamiliarity. He states that their musical abilities “seem at least to suppose some skill in nature or mathematics, Yet all this is learnt merely by practice, long habit, and custom, assisted, for the most part, with great strength in memory and quickness of invention. For no objection can be made against the natural parts and abilities of these people; which are certainly subtle and ingenious enough; only time, application, and encouragement are wanting to cultivate and improve them” (1757:196). This epistemological claim presents an interesting shade of difference. Rather than describing the character of Arab music, travelers imply that there is a fundamental commonality between the Arab and the European by using the words “knowledge” rather than “style” and “cultivation,” which implies a unilineal natural development of a natural musical ability.

A lack of scientific musical knowledge and discrepancy of musical style caused many to conjecture a break from the musical perfection of the ancients. French traveler, historian and philosopher Constantin François de Chassebœuf comte de Volney offers a good example of this reasoning practice as he conjectures about the relative age of contemporary Arab music: “It does not appear to have an earlier origin than the age of the Caliphs, under whom the Arabs applied themselves to it with the more ardour, as all learned men of that day added the title of Musician, to that of Physician, Geometrician and Astronomer; yet, as its principle were borrowed from the Greeks, it might afford matter of curious observation to adepts in that science” (1787:438-439).

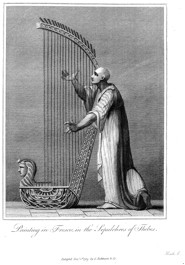

Plates 3 and 4: James Bruce’s reproductions of Pharonic panels found in Thebes in a sarcophagus of Menes (1790:128).

Believing in an unscientific and irrational contemporary Arab music was possible when contrasted with a former glory; descriptions of a once-cultivated Egyptian antiquity cast contemporary practice as corrupt. The following passage by James Bruce is excerpted from many pages of detailed organological analysis of ancient Egyptian music based on carved panels he found in Thebes (plates 3 and 4). Bruce speculated, “The whole principles, on which the harp is constructed, are rational and ingenious. … geometry, drawing, mechanics, and music, were at the greatest perfection when this instrument was made” (1790:132). the perceived lack of musical science in the shadow of ancient perfection portrayed contemporary Arabs as people who have not yet recovered the lost science of a scientifically constructed music—certainly poignant for a post-Renaissance European audience. If Arab music was not an expression of scientific justness, then what was it in the eyes of Enlightenment travelers given the critical context of the Spectator, the Tatler and other travelogues?

European Music and Tasteful Emotional Expression

The other task of music criticism in the British public sphere was the assessment of music’s proper expression of emotion. In the mid 17th century, French philosopher René Descartes posited that music is the expression or imitation of emotions (Descartes and Mizrachi 1965 [1649]). A century later, British poet William Cowper reiterated this connection in his book, The Power of Harmony (1810 [1745]).From this perspective, the role of music criticism was to determine whether or not proper emotions were expressed and whether decorum was achieved. If music had the power to balance the listener’s personality by triggering certain positive emotions, dispelling sorrow and arousing joy, music could exert a harmonious or unharmonious effect on groups of people. Therefore, the social aims for the arts were the promotion of harmony and gentility. Like the ideals of social intercourse—proper, balanced, beautiful, mannered—music was to be smooth and harmonious. Travelers’ assertions of music’s connection to emotion and descriptions of apparent breaches of decorum divide into two understandings of music’s role in Egypt and the Levant: music as entertainment and music as a cathartic tool.

Arab Music as an Offering to the Ears

In their personal narratives, travelers invariably described being invited to eat, drink, and enjoy the company of local dignitaries. For example, John Ray recounts a congenial exchange of food with an anonymous Arab in Aleppo. After eating, the Arab had his musician play on an instrument that Ray compared to an English cittern: “we expected to hear some rarity, but when I looked upon it, and saw it had but one String that was as big as a Cord of their Bows, he began to play some of their Tunes, He did this for almost two Hours and according his Opinion very harmoniously, but when we thought the time so long, that we were very glad when he had done” (1693:152). Later, Ray supports his disapproval by suggesting that the Arabs are strong in reading and law but weak in the liberal science—music included.

Other travelers speak more favorably of Arab musical entertainment. French traveler Laurent D’ Arvieux describes a series of evenings with Hassan, a tall, “genteel” eighteen-year-old “emir dervish” who had a “sweetness of Temper not to be expected in a Nation which pretends the least of all the World to Politeness” (1732:51). The music, though “doleful” matched the character of Hassan. D’ Arvieux continues, “we were afterwards entertain’d with a Consort of Voices, Violins, Tabors and Flutes, which was no less doleful than what Hassan was entertain’d with, his Wedding-night. The Tune was smooth, with very long Stops, and I could compare it to the Greeks Psalmody; but they kept Time so well, that this Arab Musick was not altogether disagreeable” (1732:52). Presented in this manner, music is as much an offering as good food or drink. The music becomes a recognizable gesture of appropriate civility from the genteel Hassan.

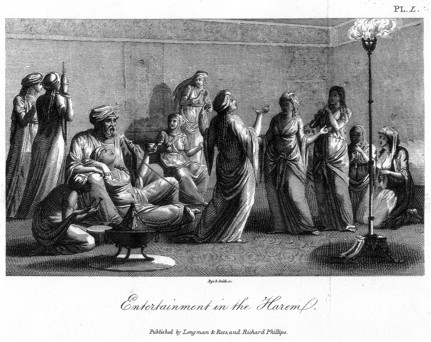

Plate 5. A reproduction of Vivant Denon’s Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt (1803) of a harem visited in Metubis, Egypt (231).

French artist, diplomat, pornographer and archaeologist Vivant Denon made a direct link between music and poor social etiquette in Cairo harems. Watching the women through colored gauze, Denon observed,

They had brought with them two instruments, a pipe and tabour, and a kind of drum, made from an earthen pot, on which the musicians beat with his hands. … Two of them began dancing, while the others sung, with an accompaniment of castanets, in the shape of cymbals, and of the size of a crown piece. … At the commencement the dance was voluptuous: it soon after became lascivious, and expressed, in the grossest and most indecent way, the giddy transports of the passions. The disgust which this spectacle excited, was heightened by one of the musicians of whom I have just spoken, and who, at the moment when the dancers gave the greatest freedom to their wanton gestures and emotions, with the stupid air of a clown in a pantomime, interrupted by a loud burst of laughter the scene of intoxication which was to close the dance. (1803:231-233)

This dramatic account of a shameful musical experience employs musical criticism to comment on manners, emotion and restraint.

Each of the above accounts link music both with setting and etiquette. In these instances, music criticism in an entertainment context outwardly comments on general impression of the event, the setting, the local characters, or the culture as a whole. By dismissing the “scientific” validity of the music, the authors veer from empirical or formal analysis to using music as a tool for social critique—expressing approval and disapproval as a matter of taste.

Arab Music as a Cathartic Instrument

From the perspective of postcolonial critique of Orientalist literature, the native is an implicit emotional antagonist to the rational Westerner. In Enlightenment travelogues, however, music’s connection to emotion also highlights a supposed functional consequence of music—its ability to assert power over emotions. The descriptions of musical experience suggest an important fundamental difference between the European traveler and the native observed: in experiencing music, the European genteel traveler controls aesthetic experience through reasoned comprehension whereas the native is subject to the power of his music, suffering under its emotional impositions. This distinction is most apparent in travelogue description of the cathartic power of Arab music.

In his travelogue, French pioneer of Egyptology Claude Étienne Savary says of the Arabs, “it is in the pathetic that they display their talents” (1786:180). He describes Arab music as pure emotion passing through the ether, unencumbered by the science of harmony. In his words, “Those nations … whose sensibility is more affected than their hearing, little capable of enjoying the charms of harmony, like the simple tones whose beauty goes directly to the soul, without requiring reflection to perceive it” (1786:180-181). Savary describes the transformation of sound into sentiment in the performance of a mawwāl (موال), a sung prelude style that is still in practice today: “It is when they recite a moal, from the movement of the romance, that the continuity of tender, affecting, and plaintive sounds, inspires a secret melancholy, which insensibly increases, and changes into tears of commiseration” (1786:180). If “hearing” is the aesthetic measurement of musical knowledge for the European, “sensing” is a suffering of the passions for the Arab. This distinction hinges on perceptive agency: measuring beauty through the experience of aesthetic distantiation versus suffering beauty through the experience of cathartic induction.

If Arab music acts on the Arab, it may be evaluated as being operational. With this logic, Savary emphasizes the necessity of music for harem women. “Joy is not banished the interior of the haram. … Gay or tender airs are sung; slaves accompany the voice with tambour de basque and castanets. … Thus do the Egyptian women strive to charm the listlessness of their captivity” (1786:194-195). In this case, music is a salve. While Savary might not be able to describe what it is, he can describe what it does.

Volney’s travelogue, which enjoyed several English publications, speaks most directly to the cathartic function of Arab music:

Their performance is accompanied with sighs and gestures, which paint the passions in a more lively manner than we should venture to allow. … To behold an Arab with his head inclined, his hand applied to his ear, his eyebrows knit, his eyes languishing; to hear his plaintive tones, his lengthened notes, his sighs and sobs, it is almost impossible to refrain from tears, which, as their expression is, are far from bitter: and indeed they must certainly find a pleasure in shedding them, since among all their songs, they constantly prefer that which excites them most, as among all accomplishments singing is that they most admire. (1787:139-140)

As with Savary, Volney describes aesthetic suffering, yet he has refined his description of the function: music works to “shed” the emotions. Furthermore, Volney’s description implies that Arab music’s cathartic induction works on anyone, though it may not be suitable to genteel tastes. These accounts describe Arab music as having certain functional emotional effects on the Arab people. Music’s double role as scientifically just and emotionally potent offers evidence that supports the notion of a universally ideal music: controlled, reasoned performance of scientific principles.

From the testimony of 17th and 18th century travelers and British gentility, music could be an ideal expression of decorum and could improve manners and morals when presented in its proper natural form. As the rising mercantile class debated its definition of itself, criticism assessed musical decorum, questioned what constituted proper entertainment forms, and explored musical uses and musical abuses. Travel accounts described wider possibilities of music’s cathartic power. Science and critique gave power to a reasoned defense of musical taste, universalizing an aspect of bourgeois political consciousness. These documents contain valuable early musicological accounts of heavy ornamentation, the use of heterophony, ritual music, a few transcriptions, and organological data that remains of interest to the historian. That said, it is with a step of caution that we reconstruct this past. I hope to have shown here that the descriptions of these early musical encounters were as politically driven as they were intellectually driven.

Though we cannot raise the dead, we may take a step further to understand the ways in which one historical cultural group studied another and how they reflected their own self-understanding in that study. In this case, Enlightenment era travelogues reveal local issues in their descriptions of distant lands. The literature examined in this paper does not define a consensus; rather, it reveals issues that colored the understanding of the music of another people. A broader study may reveal intellectual vestiges inherited from this proto-ethnomusicological literature and encourage a new level of consciousness to historical research.

1. While British interest in rare books has helped preserve this literature, it has also set high prices for access to these accounts—even high prices for photocopying fragile pages. I left London with over 100 pages of transcribed accounts from dozens of volumes of 17th and 18th century travelogues.

2. This project was made possible by UCLA’s Graduate Summer Research Mentorship Program, Professor A.J. Racy, and the British Library.

Addison, Joseph, and Richard Steele. 1889 [1711]. The Spectator. London: Longmans, Green.

Alembert, Jean Le Rond d, Richard N. Schwab, and Walter E. Rex. 1995. Preliminary Discourse to the Encyclopedia of Diderot. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bruce, James (of Kinnaird, Esq. F.R.S.). 1790. Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile, In the Years of 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772, and 1773. In Five Volumes. London: Edinburgh, Printed for J. Ruthven, Fro G. G. and J. Robinson, Paternoster-Row.

Bruyn, Kornelis Philander de. 1702. Voyage to the Levant: Or, Travel in the Principal Parts of Asia Minor, the Islands of Scio, Rhodes, Cyprus, &c.: with An Account of the most Considerable Cities of Egypt, Syria and the Holy Land: enrich’d with above two hundred copper-plates, wherein are represented the most noted cities, countries, towns and other remarkable things, all drawn to the life. London: Printed for Jacob Tonson, within Gray’s Inn-Gate in Gray’s Inn-Lane; and Thomas Bennet, at the Half-Moon in St. Paul’s Church-Yard.

Campbell, Mary B. 1988. The Witness and the Other World: Exotic European Travel Writing, 400-1600. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Chateaubriand, François A. 1811. Travels in Greece, Palestine, Egypt, and Barbary, during the years 1806 and 1807. In two volumes. Translated by F. Shoberl. London: Printed for Henry Colburn, English and Foreign Public Library, Conduit Street, Hanover Square.

Christensen, Thomas Street. 2004. Rameau and Musical Thought in the Enlightenment, Cambridge Studies in Music Theory and Analysis New York: Cambridge University Press.

Clarke, Edward Daniel. 1810. Travels in Various Countries of Europe, Asia and Africa. (pt. 1. Russia, Tartary and Turkey; pt. 2. Greece, Egypt and the Holy Land; pt. 3. Scandinavia.). 6 vol. London: Printed for T. Cadell and W. Davies Strand; by R. Watts Broxbourn Herts.

Cowper, William. 1810 [1745]. “The Power of Harmony.” In The Works of the English poets, from Chaucer to Cowper, edited by A. Chalmers and S. Johnson. London: J. Johnson etc. 519-527.

D’ Arvieux, Laurent. 1732. The Travels of the Chevalier D’ Arvieux in Arabia the Desart; Written by Himself, and Published by Mr. De la Roque: Giving a very accurate and entertaining Account of the Religion, Rights, Customs, Diversions, &c. of the Bedouins, or Arabian Scenites. Undertaken by Order of the late French King. To which is Added, A General Description of Arabia, by Sultan Ishmael Abulfeda, translated from the best Manuscripts; with Notes. 2nd ed. London: Printed for B. Barker, at the College-Arms in the Bowling-Alley, near King’s School at Westminster; and C. King, in Westminster-Hall.

Denon, Dominique Vivant Baron. 1803. Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt, In Company with Several Divisions of the French Army, During the Campaigns of General Bonaparte in that Country: Embellished with numerous engravings. Translated by A. Aikin. London: Printed for T. N. Longman and O. Rees, Paternoster-Row; and Richard Phillips, 71, St. Pauls. By T. Gillet, Salisbury Square.

Descartes, René, and François Mizrachi. 1965 [1649]. Traité des passions. Paris: Union générale d’éditions.

Diderot, Denis, Jean Le Rond d Alembert, Pierre Mouchon, and the Library of Congress. 1751. Encyclopédie. Paris: Briasson [etc.].

Dolan, Brian. 2000. Exploring European Frontiers: British Travellers in the Age of Enlightenment. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Dupré, Louis K. 2004. The Enlightenment and the Intellectual Foundations of Modern Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Frantz, Ray William. 1934. The English Traveller and the Movement of Ideas, 1660-1732. Lincoln: University Studies of the University of Nebraska.

Griffiths, J., M. D. (Member of the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh, and of several foreign literary societies). 1805. Travels in Europe, Asia Minor and Arabia. London: Printed for T. Cadell and W. Davies; and Peter Hill, Edinburgh; by John Brown, Edinburgh.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1991. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hasselquist, Frederick, M.D. (Fellow of the Royal Societies of Upsal and Stockholm). 1766. Voyages and Travels in the Levant; In the Years 1749, 50, 51, 52. Containing Observation in Natural History, Physick, Agriculture, and Commerce: Particularly on the Holy Land, and the Natural History of the Scriptures, written originally in Swedish. (Some account of Dr H. by C. Linnaeus.). London: Printed for L. Davis and C. Reymers, opposite Gray’s-Inn-Gate, Holburn, Printers to the Royal Society.

Hohendahl, Peter Uwe. 1982. The Institution of Criticism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kamps, Ivo, and Jyotsna G. Singh. 2001. Travel Knowledge: European “Discoveries” in the Early Modern Period. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave.

Locke, Ralph P. 1998. “Cutthroats and Casbah Dancers, Muezzins and Timeless Sands: Musical Images of the Middle East.” 19th Century Music 22 (1):20-53.

Love, Harold. 2004. “How Music Created a Public.” Criticism 46 (2):257-271.

Montagu, John 4th Earl of Sandwich, and John Cooke. 1799. A Voyage performed by the Late Earl of Sandwich round the Mediterranean in the years 1738 and 1739. Written by himself. Embellished with a portrait of his lordship, and illustrated with several engravings of ancient buildings and inscriptions, with a chart of his course. To which are prefixed, Memoirs of the noble author’s life, by John Cooke. London: Printed for T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies.

Niebuhr, Carsten. 1792. Travels through Arabia and Other Countries in the East. Translated by R. Heron. Edinburgh: Printed for R. Morison and Son.

Parsons, Abraham Esq. (Consul and Factor-Marine at Scanderoon), and John Paine Berjew. 1808. Travels in Asia and Africa; including a journey from Scanderoon to Aleppo, and over the desert to Bagdad and Bussora; a voyage from Burssora to Bombay, and along the western coast of India; a voyage from Bombay to Mocha and Suez in the Red Sea; and a journey from Suez to Cairo and Rosetta, in Egypt. London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, Paternoster Row.

Pitton de Tournefort, Joseph. 1718. A voyage into the Levant: perform’d by command of the late French king: containing the ancient and modern state of the islands of the Archipelago, as also of Constantinople, the coasts of the Black Sea, Armenia, Georgia, the frontiers of Persia, and Asia Minor: with plans of the principal towns and places of note, an account of the genius, manners, trade, and religion of the respective people inhabiting those parts, and an explanation of variety of medals and antique monuments / by M. Tournefort; to which is prefix’d, the author’s life, in a letter to M. Begon; as also Elogium, pronounc’d by M. Fontenelle, before a public assembly of the Academy of Sciences. London: Printed for D. Browne, A. Bell.

Racy, Ali Jihad. 1996. “Music of the Arabian Desert in the Accounts of Early Western Travelers.” Al-Ma’thurat al-Sha’bbiyyah; A Specialized Quarterly Review on Folklore (44):7-23.

Ray, John (Fell. of the Royal Society). 1693. A Collection of Curious Travels & Voyages. In Two Tomes. The First containing Dr. Leonhart Rauwolff’s Itinerary into the Eastern Countries, as Syria, Palestine, ot the Holy Land, Armenia, Mesopotampia, Assyria, Chaldea, &c. The Second taking many parts of Greece, Asia Minor, Egypt, Arabia Felix, and Petræa, Ethiopia, the Red-Sea &c. from the Observations of Mons. Belon, Mr. Vernon, Dr. Spon, Dr. Smith, Dr. Huningdon, Mr. Greaves, Alpinus, Veslingius, Thevenot’s Collections, and others. To which are added, Three Catalogues of such Trees, Shrubs, and Herbs as grow in the Levant. Translated by N. Staphorst. London: Printed for S. Smith and B. Walford, Printers to the Royal Society, as the Prices Arms in St. Paul’s Church-yard.

Rooke, Henry. 1783. Travels to the Coast of Arabia Felix; and from thence, by the Red Sea and Egypt, to Europe, containing a short account of an expedition undertaken against the Cape of Good Hope. In a series of letters. London: Printed for R Blamire, in the Strand. Sold by B. Law, Ave-Mary Lane; and R. Faulder, New Bond Street.

Sattin, Anthony. 2000. The Pharaoh’s Shadow: Travels in Ancient and Modern Egypt. London: Indigo.

Savary, Claude Etienne. 1786. Letters on Egypt, with a Parallel between the Manners of its ancient and modern Inhabitants, the present State, the Commerce, the Agriculture, and the Government of that Country: and an Account of the Descent of St. Lewis at Damietta: extracted from Joinville, and Arabian authors. In two volumes. London: Printed for G. G. J. and J. Robinson, Pater-Noster-Row.

Schueller, Herbert M. 1952. “The Use and Decorum of Music as Described in British Literature, 1700 to 1780.” Journal of the History of Ideas 13 (1):73-93.

Searight, Sarah, and Malcolm Wagstaff. 2001. Travellers in the Levant: Voyagers and Visionaries. Durham: ASTENE.

Shaw, Thomas. 1757. Travels, or Observations Relating to Several Parts of Barbary and the Levant. Illustrated with Cuts, The Second Edition with great Improvements. 2nd ed. London: Printed for A. Millar and W. Sandby.

Steele, Richard, Joseph Addison, and Alexander Chalmers. 1822 [1709]. The Tatler. London: F.C. and J. Rivington [etc.].

Thèvenot, Jean de. 1687. The Travels of Monsieur de Thevenot into the Levant. Viz. into I. Turkey. II. Persia. III. The East Indies. London: Printed by H. Clark for H. Faithorne, J. Adamson, C. Skegnes, and T. Newborough.

Thompson, Charles Traveller, Esq. 1754. Travels through Turkey in Asia, the Holy Land, Arabia, Egypt, And other Parts of the World: giving A Particular and Faithful Account of what is most Remarkable in the Manners, Religion, Polity, Antiquities, and Natural History of those Countries: with a Curious Description of Jerusalem, as it now Appears, And other Places mention’d in the Holy Scriptures. London: Printed for J. Newberry, at the Bible and Sun, in St. Paul’s Church-Yard.

Van Egmont, J. Ægigius, and John Heyman. 1759. Travels Through Part of Europe, Asia Minor, The Islands of the Archipelago; Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Mount Sinai &c. Giving a particular account Of the most remarkable Places, Structures, Ruins, Inscriptions, &c. in thes Vountries. Together with The Customs, Manners, Religion, Trade, Commerce; Tempers, and the Manner of Living of the Inhabitants. Translated from the Low Dutch. In Two Volumes. London: Printed for L. Davis and C. Reymers, against Gray’s-Inn, Holburn. Printers to the Royal Society.

Volney, Constantin François de Count. 1787. Travels through Syria and Egypt, in the Years 1783, 1784, and 1785. Containing The present Natural and Political State of those Countries, their Productions, Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce; with Observations on the Manners, Customs, and Government of the Turks and Arabs: Translated from the French. London: Printed G. G. J. and J. Robinson, Pater-Noster-Row.

Walsh, Thomas (Captain in his Majesty’s Ninety-Third Regiment on Foot, Aide-De-Camp to Major-General Sir Eyre Coote, K. B. and K. C. M. P. &c.). 1803. Journal of the Late Campaign in Egypt: Including Descrriptions of that Country, and of Gibraltar, Minorca, Malta, Marmorice, and Macri; with an Appendix; containing Official Papers and Documents. London: Printed by Duke Hansard, for T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies, in the Strand.

Wolff, Anne. 2003. How Many Miles to Babylon?: European Travels and Adventures in Egypt, 1300-1600. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.