The Sonic Structure of Shango Feasts

The Orisha religion began in Trinidad sometime in the middle to late-19th century, originating with several thousand indentured laborers (free, not enslaved) from the areas in present-day Nigeria. (The religion was long known as Shango in Trinidad, but many worshipers now prefer the name Orisha.) Based on the veneration of a pantheon of Yoruba spirits known as orishas – with attendant spirit possession, animal sacrifice, and drumming and singing—Orisha bears strong resemblances to the Yoruba-derived religions in Cuba (Santería) and Brazil (Candomblé). As in those places, Trinidad Orisha musicians use three drums. But while Cubans play bata drums, and Brazilians play Dahomean-derived peg-style atabaques, Trinidadians use a trio of bembe drums with bent sticks. Very similar bembe drums can be observed in Nigeria today.

Like elsewhere in the diaspora, Christianity plays a central role in Trinidad Orisha—though some Orisha shrines since the late 20th century have spearheaded a more “pure” Orisha practice that renounces Christianity. Historically, the Yorubas in Trinidad syncretized their orishas with the saints of the local (French) Catholic religion.[1] As Orisha practitioners in Trinidad maintained their Christianity over generations, many became Spiritual Baptists (an Afro-Protestant faith native to the West Indies), such that “Shango-Baptists” remains a common (if derogatory, in the eyes of many) moniker on the island. (The Spiritual Baptist connection remains strong, and the setting of the Orisha ethnography below is a Spiritual Baptist church.)

Being one of three main Yoruba-derived faiths in the Americas, Trinidad Orisha has received the attention of several anthropological studies.[2] These include a Herskovitsian study on the high degree of Africanisms found in Orisha (Simpson 1965); a study of syncretism in the religion (Houk 1995); a biographical sketch of the well-known Shango leader, Papa Neezer (Henry 2008), and a study of the sociopolitical legitimization of the religion (2003); studies of spirit possession in the Orisha religion in relation to trance practices of Spiritual Baptists and Hindus (Lum 2000 and McNeal 2011, respectively); and studies of Yoruba language retentions in Trinidad (Warner-Lewis 1994; 1996). However, while at least one of these anthropologists performed Orisha drums as part of his methodology (Houk 1995), no scholar has written specifically about Orisha music.[3] When one considers that drumming and singing are nearly ever-present during Orisha rituals, it becomes clear that the study of Trinidad Orisha music is long overdue in African diaspora scholarship.

In this audio essay I look specifically at the “feast”—the main, annual event held by an Orisha congregation—to explore the idea that music during Orisha rituals is much more than ancillary. Rather, Orisha feasts can be understood as sonically structured. In that sense, Orisha music and ritual are inseparable. While individual Orisha songs are typically brief, taking a wider view reveals long-form structures and a more complex relationship between Orisha music and time. Along these lines, Michael Tenzer argues that a useful concept in world music analysis is periodicity, which “orients us in music and a much larger hierarchy of time that connects to experience both at and beyond the scale of human lives” (Tenzer 2006:25). The Orisha feast periodicities herein described might be categorized as 1) hymn time; 2) Litany time; 3) drumming and ring march time; 4) manifestation time; 5) offering time; and 6) time for giving thanks. In Tenzer’s terms, Orisha music “orients” its participants in the feast, signaling the progression through different periods of the ritual, and, beyond the scale of participants’ lives, to the historicity of their tradition.[4]

The recordings included in this essay were made by me in June 2014, using a Zoom H4N handheld recorder, at an Orisha feast at the Mount Moriah Spiritual Baptist Church in Brooklyn. This church was something of a home base for me during my fieldwork, especially during the summer in 2011 when I was a regular umele drummer in the Orisha scene in Brooklyn. The umele (derived from a Yoruba word in Nigeria denoting an accompanying drum) is the smallest of the three standard bembe-derived Orisha drums, all of which are played seated with either one or two curved sticks. Drumming in Orisha can easily involve 4 to 6 hours of continuous work, usually in the middle of the night. While this was tiring, the central rituals of Orisha—namely spirit possession and animal sacrifice—are carried out mere feet from the drums (the drums being a focal point of the religion). Being a drummer at these ceremonies gave me a front row seat for the proceedings and enabled a unique perspective of Orisha ritual and structural development. Although I was not a drummer when I made the present recordings, this perspective aided me while I was attending as an onlooker, singing participant, and ethnomusicologist with recorder in hand.

While these recordings were made in Brooklyn rather than in Trinidad, for the purposes of this article they can be considered representative generally of the genre “Trinidad Orisha music” (see Bazinet 2013). Though the context of this feast is somewhat different from a Trinidadian version (indoors rather than outdoors, as would be the case in Trinidad), the music is the same. I make this statement with confidence not only based on my own frequent travels to Trinidad and to Orisha feasts there, but also due to the fact that several of the singers and drummers recorded herein split their time between Trinidad and Brooklyn, as do many other transnational West Indians. In Brooklyn, Trinidadians use music—from Orisha to soca—to recreate home in the diaspora (Bazinet 2012).[5]

In the pages that follow, I present recordings of key moments as well as, when possible, some of the best[6] performances captured from the feast. The feast happened over a period of four nights and subsequent mornings (beginning on the night of Tuesday, June 3rd, and finishing on the morning of Saturday, June 7th) and while the recordings are not presented in strict chronological order, they do give a sense of the overall progression of the ritual’s constituent songs and spiritual rites. At times I include transcriptions of music and Yoruba words, the latter of which might be thought of as “Trinidad Yoruba,” defined by scholar Maureen Warner-Lewis as “a dialect of Yoruba, though outside the approximately twenty metropolitan varieties located in Nigeria and neighboring countries” (1996:14). I have written the lyrics phonetically according to the pronunciations as I hear them, giving translations when available. Though I am an ethnomusicologist and not a linguist, I have endeavored to accurately render the dialect of Trinidad Yoruba, and more generally to present the songs in a manner faithful to the masterful musicality of the Trinidadians I work with. In order to frame these musical moments and to provide a further sense of the progression of the feast, I begin with a description of this week-long celebration.

I. ETHNOGRAPHY OF A FEAST

Tuesday night

First night of the feast, Ogun Night It is a warm June night, and some 25 people are gathered in a Spiritual Baptist church basement in Brooklyn. This space serves as the palais, the Afro-Trinidadian term for the Orisha worship space. Of the people gathered, fewer than 10 are men. The gender divide evens out as the night goes on and the overall numbers swell to around fifty. Fifty isn’t very much for an Orisha feast, but this is the first night, and the first night at Mount Moriah is always a little quiet. Leader Michael, the presiding mongwa,[7] says he likes it like that. More intimate. Later, too many people will come simply to gawk at the possessed worshippers. But no matter, for there is work to be done, spiritual work, each and every night of the feast. Because this first night is known as Ogun Night, everyone is supposed to wear red or green, traditional colors for Ogun in Trinidad. The work of this night is to call Ogun, that he might come, receive the offerings, and bless the feast. There are going to be a lot of songs for Ogun.

After a Litany lasting more than forty minutes (Leader Michael’s knowledge of this introductory section is broad), the drummers lay down the beat, accompanying the calling songs which begin with the typical Ogun Rotation, starting with “Ogun Onire,” continuing through “Ajaraja Ogun O,” “Ogun Yeye Arima Lesa,” and on down the line. All Ogun songs, for nearly an hour. One might expect that the drummers get tired, and in fact they do spell one another. In this case, drummer Earl Noel’s big brother Donald is visiting from Trinidad, and as he is wont to do, he waits for Earl to get the feast warmed up, taking over the center drum from Earl after a while. Towards the end of the Ogun set, Leader Michael stops the drummers and begins singing a new song, in a faster tempo, and on cue the drummers pick up the new beat. People start, as they say, to get “shook up.” Then, maybe fifteen minutes into this new rhythm, Leader Michael switches deities, now singing for Mama Leta[8] instead of Ogun:

Mama Leta O / Mama Leta

Mama Leta O / Mama Leta

Mama Leta O / Mama waloje[9]

This is a popular song in a lively rhythm, and the energy level is high as everyone sings along and claps. After maybe ten minutes of various Mama Leta songs in this rhythm, Leader Michael stops the drummers again, starting a new Mama Leta song, but now back in the main, slower rhythm. Mama Leta, koriko kara! The drummers pick up the beat. Almost immediately, two middle-aged women start to hold their heads and call out in raspy shrieks (“Oy!”), and the drummers encourage them; Donald, now taking over for Earl, strikes the head of the center drum with such force that I feel sure it will break. It holds, for now. If anything breaks it is the resistance of the two women against the spirit possession, and they both fall headlong into what is known as a “manifestation” of Mama Leta: attendants rush to tie brown sashes across their foreheads, and the two women, now fully embodying the elderly spirit of the mother of the earth, begin to move about the room, slowly and hunched over, like old women. This weeklong feast will be filled with spirit possessions, or manifestations, like this one, in which individuals submit their being to the spirit of an orisha, fully “becoming” that orisha for a period of one to several hours, before returning to themselves. These Mama Leta manifestations get things off to a good start.

After more Mama Leta songs, aimed at pleasing the old woman spirit, Leader Michael suddenly gets taken over by the spirit of Ogun—evident because he starts to swing his arm about in a slashing motion, as though he were holding a cutlass. On cue, another mongwa, Leader Gordon, takes over singing, and switches orishas yet again, this time back to Ogun. Ogun berele amio, Ogun berele![10] Singing for Ogun continues, until Ogun himself (now dressed in a red sash) stops the music, at which point he begins to speak—leve, tout monde! (it is common for the orishas to speak in French-Creole)—demanding everyone to rise. It has now been roughly two hours since the start of the Litany, and the Rotation has covered only Ogun and Mama Leta, a reminder that the feast is a weeklong process, and it unfolds slowly.

The offering of goats for Ogun is about to begin, and the drumming will resume, but I am tired, and decide not to stay. As I head home, I consider what a treat it is to attend a feast led by Leader Michael Osouna, who comes from Trinidad to Brooklyn to carry on this feast each year. Michael is a bigtime calypsonian in Trinidad—sobriquet Sugar Aloes—and so attending his feast is a bit like having front row tickets to a great concert. Moreover, Michael is not only an excellent singer with a sharp and distinctive voice, he also knows more Orisha songs than any other song leader I have heard. With him in fine form, the opening night went well, and I can tell: it is going to be a good week.

Wednesday night

Second night of the feast. Osain Night. Everyone is supposed to wear yellow, Osain’s color of choice. When I arrive, around midnight, a man and a woman are in the kitchen, cooking some of the four goats from last night’s offering. The opening prayers won’t begin until 1:00 am, with the Litany starting at around 1:40. The mongwa Dexter begins things tonight, though Leader Michael is by his side. (This is a good thing, because during his recitation of “Baba O,” Dexter stumbles in the order of orishas, and Michael must remind him to sing for Oya next.) Dexter’s Litany is relatively short. The Ogun Rotation starts at 2. There will be fewer Ogun songs tonight, because Ogun doesn’t come on a Wednesday night, which belongs to Shakpana, Erilay, Yemanja, and most importantly, Osain. Oftentimes, on a Wednesday night feast, there will be four different Osains at the same time. Osain is an old medicine man, and when he comes, it is to heal; he might do this by rubbing oil on someone’s ailing knee, or by giving you a big gulp of overproof rum.

Tonight, though, it is Shakpana who manifests first, on a woman—as is often the case. She comes on cue: right at the beginning of the Shakpana songs, which begin after nearly one hour of singing for Ogun and Mama Leta. Shakpana arrives at about 3:00, on a stoutly built, light-skinned Afro-Trinidadian woman wearing cornrows and a rainbow-colored dress. Various lead singers, called chantwells—Michael, Gordon, Brooks—lead the congregation through the rotation of calling (during which Shakpana comes), pleasure, work, and dismissal songs. They just start to sing songs for Osain when Shakpana returns to the heavens, leaving the Trini woman to collapse in the arms of her fellow congregants. It is 3:30 am. The drummers take a break. Later, Osain will manifest. Then it will be time to prepare for the offering to Osain of goats and fowl. If this feast were in Trinidad, there would also be an offering of the South American turtle known as morocoy, a favorite of Osain’s, but this animal is not so easily found in New York.

Thursday night

Third night. Shango Night. The mongwa will kill sheep and fowl tonight, the sheep covered in robes of red-and-white (for Shango) and green-and-white (for Oya, Shango’s wife). Tonight’s musical structure will include the full cycle of songs, from Ogun to Shango, with an emphasis on Shango songs during the offering and during Shango possessions, the sonic structure mirroring the ritual emphasis on Shango. While earlier in the week, it is primarily the main members of the church who come, beginning Thursday, and continuing on into Saturday morning, many more from the local Orisha population (mainly Trinidaians) will pass through. This means bigger crowds for singing, and it also means more drummers and lead singers. On this night, the mongwa Dedan comes. Dedan, who is young, good-looking, and strong of voice, is everyone’s favorite lead singer. When he sings it is with maximum effort, his voice coming from deep within his chest, the veins popping out on his forehead. Once Dedan arrives, Leader Michael turns things over to him. When Dedan begins, he stands in the center of the crowd, shouting at the people between lines—“vibration, man!”—and they respond by singing with vigor, reaching a new level of intensity, a new plateau in the feast. The music is sweet.

Friday night

On the final night of the feast, Friday, there are more people than there have been all week, though that isn’t necessarily a good thing for the music; sometimes a crowd encourages passivity, laxity. Early in this night’s proceedings, the singing gets weak at times. A number of the people just stand there watching. Leader Michael yells at the crowd, chastising their lack of participation. It doesn’t move them, though, for everyone seems to be waiting for two rounds of spirit possessions. The first round comes when Shango manifests on four different individuals—three men and one woman—and performs the standard feat of fire-eating (swallowing burning wicks dipped in olive oil), and blesses the congregants by rubbing a smooth thunder stone in a plate of olive oil, then rubbing the oil all over each person’s face. The second round comes much later, when the sun is coming up on Saturday morning, and Ogun manifests on Leader Dedan. This signals that the end of the feast is nigh: during this manifestation, he pulls the sword from the ground where it has been “planted” in front of the drummers for the duration of the feast. When this late-feast Ogun comes, he takes over the palais. He dances with the sword, fiercely, and enjoys the singing of the crowd. He directs a few young boys to take a turn at the drums, encouraging them, the next generation, to play and learn. He tosses to the drummers bottles of wine and Forres Park rum (the Trinidad brand), as gifts for their service during the week. When he finally leaves, and Leader Dedan falls to the ground before the sweating drummers, the music stops, and Dedan is slowly revived back to consciousness. But he is not himself just yet: rather, he asks for candy, sucks his thumb, speaks in a high-pitched voice, and answers to the name Frankie, for Ogun’s place on his body has been taken by an intermediary, child-like spirit known as a rere.

There is a break in the feast, and people eat food—roti and curried goat. There is more work to be done—implements need to be cleaned (Shango’s shepherd’s rod, Yemanja’s oars), more prayers need to be said—and many participants will stay at the church throughout the day, well into Saturday evening, playing hand drums and having a good “lime.”[11] By noon, I am exhausted, and I go home to sleep.

II. THE MUSIC OF AN ORISHA FEAST

While the previous pages describe an Orisha feast experientially, I next explain the logic and structure of Trinidad Orisha songs, making reference to specific recordings from the feast to illustrate my points. The above ethnography describes the day-to-day progression of a typical Orisha feast, implicitly demonstrating the way music tracks ritual development; in contrast, the analysis below shows more explicitly the present argument regarding the inseparable relationship of music and ritual in the Orisha religion of Trinidad.

Hymn Time

Each night of the Mount Moriah feast begins with Christian prayers and hymns.[12] This is true of most Orisha groups, since there is considerable overlap between Orisha and Spiritual Baptist church memberships. According to some participants, this beginning part of the feast is simply called “the Baptist part.” In terms of the relationship between musical and ritual time, I call this section of the feast “hymn time.” It includes the singing of two kinds of Baptist hymns, the first plaintive, the second more lively, intermixed with Christian prayers recited in English. On a typical feast night, congregants begin slowly to gather a little after 11:00 pm. It is silent in the palais at this point, but not for long. As midnight approaches, the mongwa encourages the assembly to join him in the palais by starting an old Baptist song, such as “Oh God, Our Help in Ages Past,” an early 18th century hymn written by the so-called “Father of English Hymnody,” Isaac Watts.

Audio example 1: “Oh God, Our Help in Ages Past”

In this example, Leader Michael leads the chorus in the usual Baptist lining-out style, singing each line quickly just before the slowly metered response. The chorus sings in a style that might be described as heterophonic with some added harmonies in homorhythmic texture, while the drummers play rolling patterns in free meter. After a few more similarly plaintive hymns, Michael then leads the assembled in the recitation of Christian prayers, such as the Apostles’ Creed, the Our Father, the Hail Mary, Psalms 23, 34, 121, 1, and 4, the Hail Holy Queen, and Glory Be to the Father, but also including (non-Christian) esoteric prayers from the Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses, in homage to the Trinidadian spiritism known as Kabbalah.[13]

Next is a second group of hymns, livelier than the first, with handclapping and a cheerful beat played by the drummers, as in the example, “See Me Through, Lord Jesus, See Me Through.” While the free meter Baptist hymns are characterized by long texts and dirge-like melodies, the faster “See Me Through” is composed of just a single verse, in which an aaba verse form is repeated over and over, while the drummers play a steady rhythm (which, in the Orisha context, would be identified as the faster, secondary rada beat used in dismissal songs—see below). Lyrically simple songs like this one exist mainly as oral traditions, rather than as written ones.[14]

Audio example 2: “See Me through, Lord Jesus, See Me through”

Yoruba Prayers: The Litany

After about 30 minutes, the Christian hymns and prayers are finished, and are then followed by the Litany, a set of sung prayers exclusively in (Trinidad) Yoruba language. With the shift away from English, the Litany signals the transition from Baptist to Orisha, from Christian to Yoruba, into what might be thought of as the true beginning of the feast. Leader Michael explains that the Litany should be approached in a calm and humble manner, appropriate because the point is to prepare for the orishas, to request their presence at the Orisha service:

Litany is not to be jovial. When you’re doing the Litany there’s a sort of calmliness. Not melancholy, but devotion, calmliness, humility about it. Because you are asking that they [i.e., the orishas] put their presence in. So it’s a supplication. You are asking with reverence.… So when you doing a Litany, you don’t have drum and glorifying. No.

“Irawa”

The song beginning the Litany is “Ye Irawa, Irawa O,” which has been translated as “please come, let our journey be blessed” (Aiyejina et al. 2009:133).[15] “Irawa” functions as a sonic marker signaling the start of the feast. Before it, and along with the hymn singing in English, people are often milling about, involved in a range of activities, for example, preparations for the feast being made by church mothers. Sometimes, drummers do not even enter the palais prior to the singing of this song. But when “Irawa” begins, the congregants and the drummers snap to attention, the mongwa’s high, plaintive, and solo syllable “Ye!” piercing the air, announcing the start of the feast.

Audio example 3: “Ye Irawa, Irawa O”

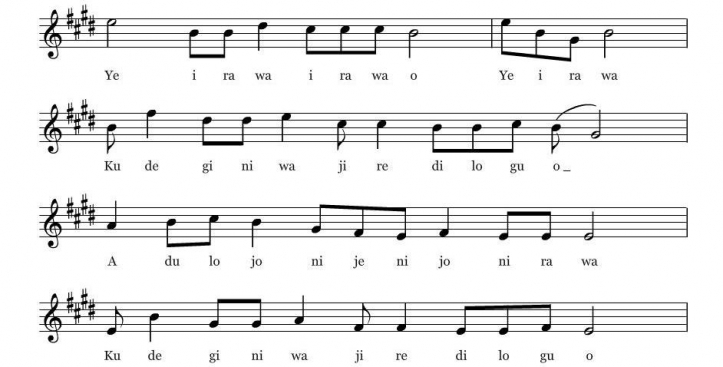

The melody of “Irawa” outlines a gradually descending contour, with stepwise motion and arpeggiations through notes aligning with the diatonic Western major scale.[16] It spans more than an octave, spun out over several phrases corresponding to five lines of poetry, and its length and range are unlike most Orisha songs. Distinct harmonies are not a regular feature of Orisha music, which tends to promote unison singing, but in the excerpted performance of “Irawa” the congregation often creates parallel melodies. A second chantwell can be heard leading the responses, becoming something of a second leader, filling in the melodic gaps with a quasi-lining out style of singing. Between the congregation’s harmonies, the shifting focus on multiple lead singers, and the rolling drums in free meter, “Irawa” is a striking musical example. (In the following notation, the bar lines divide the five lines of text, while the note durations approximate the relative rhythm of this free flowing musical work.)

Figure 1. “Ye Irawa, Irawa O”

The song also structures coordinated movement: during four repetitions of the song, the members turn and face one of four directions, symbolizing east, west, north, and south. When the mongwa begins singing “Irawa,” he stands before the drummers, and the congregants rise to their feet and do likewise. The mongwa recites the five-line stanza, which is then repeated exactly by the congregation, in harmony, four times total (four calls and four responses). For the first repetition, the congregants face the drummers, along with the singing mongwa. Second, the entire congregation turns their bodies to face to the back. Third, they face to the right. For the final repetition, the assembled face to the left.

Figure 2. Facing the drummers during “Irawa,” mongwa in yellow cap at left

“Baba O”

The next sonic marker in the Litany is the song “Baba O.” The lyrics praise the orishas, calling out “baba/father,” “mo juba/I praise you.” In performance, “baba” is replaced by a different orisha in each repetition of the verse, until each of the orishas is named in order. Brooklyn mongwa Gordon likens it to the recitation of Catholic prayers, saying that this verse “is a form of doing the rosary, where you call the orisha one by one.” The “Baba O” sung for Ogun is as follows:

Ogun o

Mojigbe rele

Ogun o, ni wolo, eri jaja

Orisha roko arimole

Ogun o, mojigbe rele

Ye shole abakuso

The elasticity of the “Baba O” format is such that an individual mongwa can insert his personal style and preferences into its repetitions. For instance, the more syncretic-minded might sing for La Divina Pastora (the Catholic “black Virgin” whom Trinidadian Hindus call Sipari Mai), whilst those with an interest in Afrocentric innovations might sing for Eshu (rejecting the Christian-centric Devil associations) or for the Nigerian Ifá divinity, Orunmila, who was not traditionally known in Trinidad. In this way, “Baba O” is a flexible prayer-song, allowing for the divergent inclinations of song leaders, its unique periodicity enabling the expression of certain traditional, historical, and even political allegiances. Congregants can also make their own inclinations heard during the “Baba O.” In addition to simply repeating the words, congregants accompany the “Baba O” responses with sounds and actions that express their recognition or endearment towards the particular orisha being named. For instance, when the mongwa sings the name of Mama Leta, congregants might bend down briefly to touch their fingers to the ground, in acknowledgement of the deity’s connection with the earth. When Shango’s name is called, congregants call out with the ululations known as sababo.

Audio example 4: “Baba O”

“Baba O” is a six-line stanza outlining a pentatonic major scale (5 6 1 2 3 5), and featuring prominent arpeggiations and melodic leaps including several thirds, a descending fourth, and two descending sixths. Unlike “Irawa,” with its stepwise scalar passages, “Baba O” relies on greater usage of intervallic leaps and skips, and while the melody of “Irawa” soars into the high range, “Baba O” features much more emphasis on the lower register. In the following notation, I have divided the free meter verse into six phrases, with phrase-endings determined (as in “Ye Irawa, Irawa O”) by a long-held final note. At the end of the second phrase, note that this melody includes an example of melisma, uncommon in the mostly syllabic Orisha repertoire.

Figure 3. The call to the orishas, “Baba O”

“Sheri Egbo”

Following “Baba O,” mongwas add a number of free meter verses to their individual Litanies, such that a Litany can be quite long. The Litany from which this is excerpted lasted 45 minutes, completing its structural arc finally with the next example, “Sheri Egbo.” One mongwa translates this song as “sharing the oil around the place,” for “egbo” means oil, and because the song accompanies libations. In the song, a dozen or so central members of the congregation take in their hands the liquids on the floor before the drummers, surrounding Ogun’s sword—oil, honey, milk, molasses, cologne, water, a goblet, a calabash, candles, and so on. Leader Gordon explains the “Sheri Egbo” procession around the palais, this giving of libations, as recognition of the “motherland.” (And given Gordon’s location, in Brooklyn, one might wonder whether the motherland referred to is Africa, or Trinidad.)

You go to the four cardinal points. You have to give that libation because you are calling. You have to remember now, you are not in your motherland, or where you would consider, where your foreparents come from. So you go to the four points. And then you call.

Figure 4. Ritual liquids in front of the drums; Ogun’s sword in the ground at left

Audio example 5: “Sheri Egbo”

As the sung repetitions of “Sheri Egbo” continue, the chosen congregants carry their items to the ritually important locations in the worship space, which includes the chapelle (a small room, adjacent to the palais, housing various ritual objects) and the four corners, representing the four cardinal points, east, west, north, and south. When they have made the rounds, they return to the area of the sword, and begin to sing the opening group of songs for Ogun.

The Drumming Begins

At the close of the Litany, the congregation begins a new group of songs, with drumming accompaniment. These songs are for Ogun. Whereas the preliminary sections of the feast were performed in free meter, now the drummers start to beat in time, using the primary Orisha rhythm that drummer Earl Noel calls “straight Orisha.” The songs are performed in medley-style, one short song after another. The local term for these groupings is “Rotation.” (In Cuba, the equivalent term is tradado.) Songs progress in certain orderings, with typical progressions from song to song, and over a longer period of time, with typical progressions from orisha to orisha. As drummer Junior Noel puts it, “It’s like the alphabet, from A to Z. You have a Rotation.” Generally speaking, the Orisha song “alphabet” progresses from Ogun to Shango—the two most important orishas in Trinidad—interspersed with songs for Mama Leta, Shakpana, Raphael, Oshun, Ibeji, Erilay, Yemanja, Osain, Oya, and a few others. A full progression of songs for all the orishas can take several days. But each night of the feast, songs begin with Ogun.

The opening Ogun songs follow a standardized progression, consisting of four minor key songs that modulate to major usually around the fifth song. The minor key tonality distinguishes these first Ogun songs, departing from the preliminary music (Christian hymns and Yoruba Litany songs), which was all in a major key, the tonal shift helping to signal a progression in the ritual.

In the accompanying recording, following the Litany, Leader Michael pauses to lead a brief recitation of the Christian prayer, “Glory Be,” before beginning the minor-key “Ogun Onire,” a song whose lyrics refer to Ogun’s mythical associations with the location of Ire in Nigeria. In the audio example, the percussion enters with the second repetition, first the drummers (the heartbeat of the bo, followed by the high-pitched, rolling umele, and finally Earl Noel playing the center drum—or bembe—which “speaks”), then intermittent handclapping, and eventually the gourd-shakers called shac-shacs. The songs move on to the minor-key “Ajaraja Ogun O” (1:37), “Feregun Abani” (2:31), and “Ogun Lalala Urele” (3:24), then finally modulating to the major-key “Ogun Yeye Arima Lesa” (3:48). The following transcription includes the opening song melody and the main drum parts of the primary Orisha rhythm, which might be characterized as a swinging 4/4 beat rhythm with syncopated triplet accents throughout.

Audio example 6: Opening Ogun Songs

Figure 5. First Ogun song: “Ogun Onire”

With the opening Ogun Rotation, not only does the drumming begin in earnest, but also members of the congregation start to move in a ring, in a kind of dance which only occurs at this point in the feast. In terms of the sonic structure, I call this “ring march time.” Elder drummer Mr. Burton describes the march thusly: “And then you beat the drum. Then people would make the rings, and then they walk around the rings.” The ring march is performed by the same group of twelve congregants who carried the ritual liquids throughout the palais during “Sheri Egbo” at the end of the Litany. Still holding the items, these congregants circle the area in front of the drums, in a single-file marching dance—left-right-right-left, 1-2-3-4. When the chantwell changes to a new song, the dancers spin around, touch the ground, and reverse the direction of the circle, now moving the ring in the opposite direction. Throughout the first several Ogun songs, this ring continues in the same fashion, changing direction with each new song, the dancers literally embodying and enacting the concept of “Rotation.” One by one the dancers return their ritual items to the mongwa standing in the center of the ring. When all items are returned, dancers blend back into the congregation, which normally coincides with the major-key modulation to “Ogun Yeye Arima Lesa.” Similar circular introductory dances have been noted by researchers in Igbogila (Nigeria), Bahia (Brazil), and among the Iyesá in Cuba (Drewal 1989: 227; Delgado 2001), suggesting that this dance has deep transnational roots.

Figure 6. Making the rings for Ogun’s songs

Like participant movement toward the four corners and the four directions, the ring march is one of several coordinated music-directed movements in the early part of the Orisha feast. After it, singing for Ogun continues, but there are no more group dances at the feast. Now, the main action in the feast is spirit manifestation, for which song rotations with drumming will continue for hours, being interrupted occasionally by a spirit who wishes to speak to the congregation. The music can be organized into three main song types: those for before, during, and at the end of spirit possessions.

Song Types for Spirit Possessions

Maureen Warner-Lewis has found that Trinidad Yoruba songs are not homogeneous; they historically encompassed a range of genres and purposes (1994; 1996). In the main part of the Trinidad Orisha feast, song types are organized with the aim of orchestrating spirit possessions—manifestations—by encouraging their onset (“calling” songs), attending their duration (“pleasure” or “work” songs), and bringing them to an end (“dismissal” songs). Leader Gordon explains some of these types as follows:

There are songs for calling. That is why, when we start, we start with certain songs, calling songs. And you will find if Ogun want a pleasure or a dance, you give him pleasure song. It have song for, also, too, when they’re working. Like if Ogun come and he want to anoint his children, who he know is under his head. … And then again sometimes you change it up, because you need that vibration. When you are carrying on a prayers you need that vibration. So you find, instead of singing a calling song you might go to a pleasure song, and just through that pleasure song, the vibration does start to bring out, and would help call that manifestation that was supposed to come.

Similarly, Leader Michael told me, “it’s through the vibration now, you get a connection to the outer world, where the spirit world is, and they could come forward.” In musical performance, this vibration is achieved in part through the collective attention of the congregation, as people clap, singers shout, and drummers whoop and strike their instruments with apparently inextinguishable energy. But aside from such willed energy, many songs which are considered “calling” types also have an inherent tendency towards the creation of that vibration through the manipulation of musical time, as shown in the example of the popular Ogun song, “A Gaile, Etuma Gaile.”

Calling Songs

This example of a calling song is comprised of two alternating Ogun song-phrases, one four bars in length, and one a single bar. In the recorded performance, during four-bar sections the sung lines allow more sonic space, which Earl, the center drummer, partially fills by playing longer phrases. The one-bar phrases are immediately denser, however. In the first transition to the single bar phrase (0:38), note the instant change in energy. On one side of the palais, a woman starts screaming, while someone else sings a long-held, slowly rising note. On the other side of the palais, a man shouts, “Go, go, go, go!” Earl begins to play the center drum in shorter drum bursts, interspersed with drum rolls aimed at enhancing the energy. After several repetitions, Leader Michael returns to the four-bar song, granting a respite, from which he works the group back to the one-bar call.

Audio example 7: “A Gaile, Etuma Gaile”

Chantwell’s call | Choral response | Number of bars |

A gaile, etuma gaile | A gaile, etuma gaile | 4 |

Ogun onire | Gaile! | 1 |

Figure 7. Regressive bar structure in the Ogun song “A Gaile.”

This type of long-to-short regressive bar structure makes the music seem as though it is getting faster.[17] A chantwell who notices congregants in a pre-possession state (individuals getting “shook up”: experiencing tremors, holding their heads, shouting out exclamations) might choose to begin a song sequence progressing toward a song with short phrase lengths, thus maximizing the feeling in the palais. Or, the chantwell might simply repeat the one-bar song over and over, unrelenting until the manifestation is enacted.

Long-to-short structural song progressions are found throughout the repertoire of Trinidad Orisha music. The chantwell exerts total control over the length of time each song is sung, switching to the next song when he (or, occasionally, she) feels it is the right time. In all cases—for Ogun, Shakpana, Osain, Erilay, Yemanja, and others—these long-to-short progressions can be used, by the effective chantwell, as foundations for enhancing the vibration and calling the orishas. Through the use of calling songs like “Gaile” and others, the chantwell can lead Orisha devotees to spirit possessions; in other words, the structure of Orisha music leads the congregation towards manifestation of the orishas, which might be thought of as the primary goal of the Orisha feast.

Songs for Pleasure and Work

Sometimes spirits manifest to dance, and in that case the chantwell leads the group in a pleasure song for the orisha who dances before the drums. But nearly always, when an orisha comes, it is to work, as in the case of the following example, beginning with a song for Shango’s wife, Oya, moving to two songs for Shango (“Yeye Aniro,” “Shango Tete Malaw”), and then back to Oya.[18] When this performance was recorded, Shango had manifested on three different people. The “work” in this case involved the mongwa anointing the congregation with oil, dipping a “thunder stone”—a mango-sized very smooth stone commonly found at an Orisha palais—in a plate of olive oil, then placing the stone on each congregant’s forehead, making the sign of the cross and rubbing the oil all over the face and scalp of the individual. The music in this example accompanied that activity.

Audio example 8: “Ye Oya, Emi Oya”/“Ye Ye Aniro”

The remarkable performance begins with Leader Michael’s voice, being strongly supported by popular chantwell Leader Dedan, whose rhythmic shouts (“sing the thing!”) make him almost like a second chantwell (the secondary functions mirrors Gordon’s role during the Litany, discussed above). Dedan also sings in a doption style (a sort of rhythmic hyperventilating which hip hop fans might think of as Spiritual Baptist beatboxing). Meanwhile, in the congregation, people sing and clap loudly, including a syncopated tresillo clap [♩. ♩. ♩]. Others whoop, shout, moan (“ay-ay-ay!”), bluster with their lips, make high-pitched twittering noises, and play the shac-shacs. The drummers—led now by Brooks at the center drum—lock into a solid and fast ostinato pattern, supporting the voices and allowing them to take center stage. The whole performance is one of unified ecstasy, and musical mastery, the hard-won results of singing for hours. All this combines into a musical tour de force, a kind of peak in the feast (and it is no coincidence that the music and ritual reach this peak simultaneously). This example perhaps best represents what made me fall in love with Trinidad Orisha music: the collective musical power and joy practically demand that one sing and clap along. In that moment I wished that I was playing the drums rather than holding my digital audio recorder.

Dismissal Songs

The peak of a spirit possession must eventually end, which is the function of the following song type: dismissal songs. While the previous example detailed a Shango possession at the end of the week, this example considers a dismissal song for a manifestation of the spirit Shakpana, which took place earlier in the feast (chronologically speaking). The recording begins at the end of a long Rotation of pleasure songs for Shakpana (who was manifesting on the woman in the rainbow dress on the Wednesday night of the field journal above). Shakpana had been in the palais for quite a while, and it was time to move on. This was indicated, for one thing, in the fact that the woman dancing Shakpana was repeatedly pointing at her chest with two thumbs, then up to the heavens with her forefingers. So the lead drummer, Leader Brooks, signaled for an end to the pleasure song “Koriwo,” and immediately started the dismissal song (“Majangwe”) for Shakpana.

Audio example 9: “Ye Shakpana, Tini Majangwe”

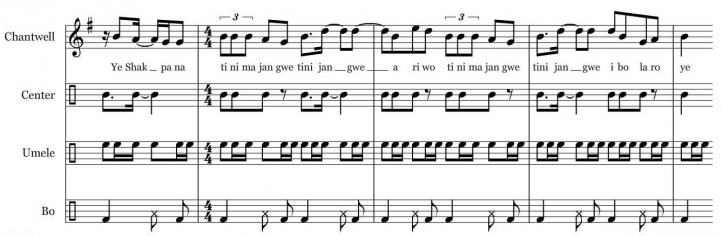

Figure 8. “Ye Shakpana, Tini Majangwe”

In the recording, listen to how Brooks takes advantage of the momentary silence to begin softly singing the quick and oddly metered tune, with its syncopated rhythms extending over 14 bass beats (written in my transcription as a pickup bar of 2/4 followed by three bars of 4/4). Note the new rada rhythm.[19] Upon the first repeat, the congregation starts to sing and clap vigorously, and shortly after that, the drums come in. Perhaps due to the challenge of singing this rhythmically complex song and also playing the lead drum, Brooks’ voice drops out shortly after the drums begin, and chantwell Steve takes over, soon after which (about 1:00) the Shakpana-dancer calls out in a gravelly shout, perhaps in recognition that this song signals it is time for Shakpana to leave. Still, Shakpana did not leave right away, and after a few minutes of singing this song, Brooks stopped the drums, waited for the singers to stop, and began singing for the next orisha in the cycle, Osain, switching back to the primary Orisha rhythm. Nearly ten minutes later, the Shakpana dancer finally collapsed into the arms of nearby congregants, apparently unconscious. Musical structure and ritual behavior conspire to transmit the following message: Shakpana’s time at the feast was over; it was time to give attention to Osain.

The song performance can be considered typical of dismissal songs at an Orisha feast. Such songs are clearly delineated by the drumming rhythms: while, up to now, nearly all songs have been played in the primary Orisha beat, dismissal songs are mostly played in the fast, secondary rada rhythm. (This is the same beat as in the Baptist song “See Me Through,” above.) The abrupt rhythmic change makes audible the impending end of the possession. Dismissal songs are often relatively short, as shown above when the musicians chose to move on with songs for the next spirit in line, Osain.

A Song of Thanks: “Mo Dupwe”

So far, I have described preliminary Christian and Yoruba prayers and songs, the beginning of the drumming with Ogun songs, and the song types that accompany spirit possessions. There are other songs for animal sacrifices (i.e., “offerings”), which I won’t describe in detail here, but which involve a basic continuation of the drumming and singing. As I made clear in the ethnographic section above: feasts are slow-developing, and after the Litany, the drumming goes on all night. But as with spirit possessions, eventually the drumming must stop. The congregation offers thanks to the orishas in a final song, “Mo Dupwe.”

In Yoruba, “mo dupe” means “thank you.” (In this song, the “pwe” sound can be understood as part of the local dialect of Yoruba.) Similar to the “Baba O,” this song is repeated as each orisha’s name is inserted into the verse. It is a simple song in a major mode with a straightforward sentiment, and is sung normally at the end of Thursday night, aka Shango night (really Friday morning), when the offering stage has been concluded, and the feast is ready to move on to the celebratory Friday night session. Like the songs of the Litany, “Mo Dupwe” is performed without drumming accompaniment – thus providing a sonic return to the feast’s opening – and loosely in the following metric arrangement.[20]

Figure 9. “Mo Dupwe”

III. CONCLUSION: SONG AS STRUCTURE

This audio essay has provided descriptions in word, image, transcription, and audio files, of the logic, sound, and types of Orisha songs. This descriptive work is important and necessary because, first, unlike the music of closely related Santería in Cuba, Trinidad Orisha music is not particularly well understood in the field of ethnomusicology. Second, these descriptions support an analytical framework suggesting that, in the Orisha religion, songs are central to the structure of Orisha rituals. Looking at Orisha music in terms of its large-scale periodicities (Tenzer 2006) reveals a simultaneity of musical and ritual time in the religion.

Beyond lending shape to ritual structures, the periodicities of Orisha music—the introductory moment I call “hymn time,” the flexible “Baba O” verses—can be seen as providing space for Orisha’s eclectic syncretism (Houk 1995), important for Orisha society because nearly all Orisha worshipers are also Christians: Catholic, Anglican, or Spiritual Baptists (this last affiliation is especially strong, explaining the common moniker “Shango-Baptist”). “Hymn time” allows for the expression of allegiance to Christ (not that Christianity is completely confined to this introductory moment, as shown in the brief recitation of “Glory Be” before the Ogun songs in the example above). The “Baba O” allows for the expression of a range of allegiances.

Orisha music periodicities also delineate clear boundaries, keeping traditional Yoruba time and space intact, as in the distinct shift from “hymn time” to “Litany time” and the accompanying immediate transition from English to (Trinidad) Yoruba. The Orisha song repertoire is a vehicle of Yoruba language retention in Trinidad, as in lyrics making specific references such as praise, oil, Ogun origin myths, and thanks. Even if that language is in a local (Trinidadian) dialect, it is still recognizable as Yoruba (Warner-Lewis 1996). Retentions are also embodied in participant movements during “ring march time,” honoring the directions and marching in a ring, the latter of which has been specifically noted historically across the diaspora. Retentions further exist in the basic duality of the overall ritual structure, which begins with prayers (or prayer-songs) and moves on to songs with drumming accompaniment, a form echoed in the rezos-cantos ritual structure of Cuban Santería (Manuel and Fiol 2007). The interrelationship of music and ritual in the Orisha religion—in which musical and ritual development are coterminous—enables the survival of a 19th century oral tradition in the modern and transnational 21st century.

The maintenance of ritual structures through music can link people through history, illustrating a “hierarchy of time” extending “beyond the scale of human lives” (Tenzer 2006). In this way, the performance of Orisha music connects the present generation with previous ones; the Brooklyn diaspora with Trinidad; and Trinidadians with orisha devotees in Cuba, Brazil, Benin, and Nigeria. Though non-ethnomusicological academic studies do not often take music seriously, this study suggests that music is centrally involved in the process, practice, and experience of African diaspora culture, as exemplified by the Orisha religion of Trinidad.

Bibliography

Aiyejina, Funso, Rawle Gibbons, and Baba Sam Phills. 2009. “Context and Meaning in Trinidad Yoruba Songs: ‘Peter Was a Fisherman’ and ‘Songs of the Orisha Palais.’” Research in African Literatures 40(1):127-136.

Altmann, Thomas. 1998. Cantos Lucumí: A Los Orichas. Brooklyn, NY: Descarga.

Apter, Andrew and Lauren Derby, eds. 2010. Activating the Past: History and Memory in the Black Atlantic World, Newcastle on Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Barros, José Flávio Pessoa de. 1999. A Fogueira de Xangô, o Orixá do Fogo: Uma Introduçã à Música Sacra Afro-Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Intercon, Uerj.

Bazinet, Ryan. 2012. “Shango Dances across the Water: Music and the Reconstruction of Trinidadian Orisha in New York City.” Re-Constructing Place and Space: Media, Culture, Discourse and the Constitution of Caribbean Diasporas, edited by Kamille Gentles-Peart and Maurice L. Hall, 123-147. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

———. 2013. “Two Sides to a Drum: Duality in Trinidad Orisha Music and Culture.” Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York.

Carr, Andrew. [1955]1989. A Rada community in Trinidad. Trinidad, W.I.: Paria Pub. Co. Ltd.

Clarke, Kamari. 2004. Mapping Yorùbá Networks: Power and Agency in the Making of Transnational Communities. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Delgado, Kevin. 2001. “Iyesa: Afro-Cuban Music and Culture in Contemporary Cuba.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

Drewal, Margaret Thompson. 1989. “Dancing for Ogun in Yorubaland and in Brazil.” In Africa’s Ogun; Old World and New, edited by Sandra T. Barnes, 199-234. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Falola, Toyin and Matt D. Childs, eds. 2004. The Yoruba Diaspora in the Atlantic World, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Forde, Maarit and Diana Paton, eds. 2012. Obeah and Other Powers: the Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing. Durham: Duke University Press.

Glazier, Stephen. 1983. Marchin’ the Pilgrims Home: Leadership and Decision-Making in an Afro-Caribbean Faith. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Henry, Frances. 2003. Reclaiming African Religions in Trinidad: The Socio-Political Legitimation of the Orisha and Spiritual Baptist Faiths. Trinidad: University of West Indies Press.

———. 2008. He Had the Power: Pa Neezer, the Orisha King of Trinidad. A Personal Memoir. San Juan, Trinidad and Tobago: Lexicon.

Houk, James. 1995. Spirits, Blood, and Drums: The Orisha Religion in Trinidad. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Law, Robin. 2004. Ouidah: The Social History of a West African Slaving ‘Port,’ 1727-1892. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

Lum, Kenneth Anthony. 2000. Praising His Name in the Dance: Spirit Possession in the Spiritual Baptist Faith and Orisha Work in Trinidad, West Indies. Australia: Harwood.

Mann, Kristin, ed. 2001. Re-thinking the African Diaspora: the Making of a Black Atlantic World in the Bight of Benin and Brazil. Portland, OR: F. Cass.

Manuel, Peter and Orlando Fiol. 2007. “Mode, Melody, and Harmony in Traditional Afro-Cuban Music: From Africa to Cuba.” Black Music Research Journal 27(1):45-75.

Matory, James Lorand. 2005. Black Atlantic Religion: Tradition, Transnationalism, and Matriarchy in the Afro-Brazilian Candomblé. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

McDaniel, Lorna. 1994. “Memory Spirituals of the Ex-Slave American Soldiers in Trinidad’s ‘Company Villages.’” Black Music Research Journal 14(2):119-143.

McNeal, Keith. 2011. Trance and Modernity in the Southern Caribbean: African and Hindu Popular Religions in Trinidad and Tobago. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Palmié, Stephan. 2008. Africas of the Americas: Beyond the Search for Origins in the Study of Afro-Atlantic Religions, Brill.

Parés, Luis Nicolau. 2013. The Formation of Candomblé: Vodun History and Ritual in Brazil. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Peel, J.D.Y. 2000. Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Putnam, Lara. 2013. Radical Moves: Caribbean Migrants and the Politics of Race in the Jazz Age. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Schweitzer, Kenneth. 2013. The Artistry of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming: Aesthetics, Transmission, Bonding, and Creativity. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Simpson, George. 1965. The Shango Cult in Trinidad. Rio Piedras: Institute of Caribbean Studies, University of Puerto Rico.

Sofela, Babatunde. 2011. Emancipados: Slave Societies in Brazil and Cuba. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Solís, Ted. 2012. “Thoughts on an Interdiscipline: Music Theory, Analysis, and Social Theory in Ethnomusicology.” Ethnomusicology 56(3):530-554.

Sum, Maisie. 2011. “Staging the Sacred: Musical Structure and the Processes of the Gnawa Lila in Morocco.” Ethnomusicology 55(1):77-111.

Tenzer, Michael. 2006. “Analysis, Categorization, and Theory of Musics of the World.” In Analytical Studies in World Music, edited by Michael Tenzer, 3-38. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Velez, Maria Teresa. 2000. Drumming for the Gods: The Life and Times of Felipe Garcia Villamil, Santero, Palero, and Abakua. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Villepastour, Amanda. 2010. Ancient Text Messages of the Yorùbá Bàtá Drum: Cracking the Code. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Warner-Lewis, Maureen. 1994. Yoruba Songs of Trinidad: With Translations. London: Kamak House.

———. 1996. Trinidad Yoruba: From Mother-Tongue to Memory. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Williams, Mervyn Russell. 1985. “Song from Valley to Mountain: Music and Ritual among the Spiritual Baptists (‘Shouters’) of Trinidad.” Master’s thesis, Indiana University Department of Folklore.

Notes

[1] Though a British colony, French Catholics dominated European settlement on the island beginning in the late 18th century. As an example of Yoruba-Catholic syncretism, in Trinidad the orisha Ogun, god of war and iron, is also called St. Michael – who is depicted on old lithographs with an iron sword fighting demons. Each orisha/saint is associated with certain colors and offerings, though these often differ throughout the diaspora; the red for Ogun in Trinidad is not used in Nigeria, for instance.

[2] These studies can be contextualized within the ever-expanding body of literature on African-derived religious formations in the Atlantic world. Recent examples in this very broad field include Peel 2000, Mann 2001, Clarke 2004, Falola and Childs 2004, Law 2004, Matory 2005, Palmié 2008, Apter and Derby 2010, Sofela 2011, Forde and Paton 2012, Parés 2013, and Putnam 2013.

[3] This omission can be contrasted with the considerable body of musical studies on Santería in Cuba, including Altmann 1998, Velez 2000, Manuel and Fiol 2007, Villepastour 2010, and Schweitzer 2013. Meanwhile, descriptive studies of Yoruba-derived music in Brazil are limited (similar to studies of Trinidad Orisha music); one of the few descriptive studies is Barros 1999.

[4] In her study of Moroccan Gnawa music, Maisie Sum uses periodicity as an analytical concept to approach “the correlation between ritual and trance phenomena, and distinguish subtleties between sacred and secular musical processes” (2011:80). While Sum is mainly looking at the relationship between micro and macro musical periodicities within the performance of a single musical work in different contexts, my own study is focused on large-scale periodic structures and their correlation with sacred ritual development.

[5] Readers can compare my Brooklyn recordings to Trinidadian recordings such as Songs of the Orisha Palais (2005), or any of Ella Andall’s Orisha CDs, such as Ṣango Ba Ba Wa (2004).

[6] “Best,” in this case, refers to moments of greatest collective participation, strong vocal or percussive performances, or moments when the singers were closest to me and my hand-held audio recorder, providing greatest clarity and definition between the vocals and the drums.

[7] In Yoruba, mongba means priest. In Trinidad, this word is pronounced as mongwa, mongba, amambwa, and other variations. Mongwa is the variant I hear most often. Most often, Orisha worshipers refer to their priests using the Baptist term, Leader.

[8] Orisha practitioners say that Mama Leta is equivalent to the Yoruba orisha Onile.

[9] Transliterations are all my own.

[10] “Ogun asks for me” (Warner-Lewis 1994:44).

[11] Trini slang for hanging out with friends and family.

[12] In the structure of beginning in prayer without drumming, later moving on to songs with drumming, Trinidad Orisha music mirrors the structure of its diasporic relative, Cuban Santería, which begins with rezos (prayers) and moves on to cantos (songs) (Manuel and Fiol 2007:49).

[13] The Trinidad Kabbalah is not associated with Judaism, but rather with books of magic circulated in the Caribbean in the early 20th century. See Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, Oxford University Press, 2010.

[14] See Glazier 1983; Williams 1985; McDaniel 1994.

[15] The song is very old, having been part of Shango tradition in Trinidad since at least the 1930s, when the Herskovitses recorded Andrew Biddeau singing it in Laventille as part of their historic Trinidad recordings. And if it was there in the 1930s, it would logically date to the century prior, contact between West Africa and Trinidad having been cut off after about the 1860s. See the final track on Smithsonian Folkways CD HRT15020, The Yoruba/Dahomean Collection: Orishas Across the Ocean.

[16] In general, when I say “major” and “minor” I am referring to the 3rds (and sometimes 7ths), not to be confused with Western major and minor tonalities. Generally speaking, researchers have noted the minor melodies of Shango songs (e.g. Warner-Lewis 1996), but during my dissertation research, I compiled a database of nearly 200 Trinidad Orisha songs, more than 70% of which I characterize as outlining a major mode. I have never heard practitioners speak about major or minor tonalities.

[17] Regressive bar structure is also part of the form of the opening Ogun Suite. In the first three songs (“Ogun Onire,” “Ajaraja,” and “Feregun Abami”), the song bar lengths regress from 6 to 2 to 1, and during the one-bar “Feregun,” people often begin to shout.

[18] Songs for the husband and wife Shango and Oya are often grouped together.

[19] The term almost certainly originates with the Trinidad Rada, a Dahomey-derived Afro-Trinidadian religious group who worship vudunus, not orishas. (See Carr 1955.) Smaller than Orisha, the Rada persist in the practice of a single Trinidadian family – the Antoines of Belmont. One of their main drum rhythms closely resembles the so-called rada rhythm of Orisha.

[20] “Mo Dupwe” is not included in my group of Brooklyn 2014 recordings, but a version of it can be heard on the CD Songs of the Orisha Palais (2005).