Calling Each Other To Prayer: Group Song in British Reform Synagogues

In the 2014 film The Theory of Everything, Jane Hawking sits down with her mother and a cup of tea to describe the frustrations of being both wife and caretaker to her husband, physicist Stephen Hawking. Jane’s mother listens to her daughter describe her physical toil and her emotional isolation, and comes up with a possible source of stress relief. “Jane, I think you should join the church choir.” Jane responds, “That is the most English thing anyone has ever said.” Beneath Jane’s dry wit is a significant kernel of truth. Group song, whether in formal choirs or in informal social settings, has been a marked feature of British cultural life for several centuries, and the practice continues today. One of the hallmarks of the Church of England is its choral tradition, which descends from the fourteenth-century tradition of English choral liturgical singing (Samama 2012:98). Choral societies and choral festivals are popular all over the UK, and private foundations raise significant sums of money specifically to fund youth choirs. Many regions of the UK have their own local traditions of group song, ranging from pub singalongs to the male-voice hymn choirs of Wales.

Jewish communities in Britain enjoy group singing as much as any other British Christian or secular community. Especially in congregations belonging to the Movement for Reform Judaism (MRJ), both choral and congregational harmony infuses worship. On any given Sabbath morning, the service leader of the week at Cambridge’s Beth Shalom congregation will start the service with “Mah Tovu,” (“How Beautiful Are Your Tents”) the prayer that opens the Sabbath morning service, and the congregation will sing it as a two-part canon. Later in the service, they may sing another two-part canon setting of the final verse of Psalm 150, and render Louis Lewandowski’s setting of the final lines of Psalm 92 in semi-improvised harmony. Congregants at London’s Finchley Reform Synagogue (FRS) sing in harmony with each other under the careful but informal instruction of their cantor. Some MRJ congregations maintain dedicated synagogue choirs, which sing choral settings of the liturgy and the Psalms that date from the beginnings of Jewish Reform in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as the occasional newly-composed piece. However, British synagogue choirs rarely sing to a silently appreciative congregation. In some communities, the congregations may choose to sing along with the choir; other communities have chosen to disband the choir in order to facilitate congregational song. Beyond the synagogue, Jewish performance choirs offer harmonic renditions of Jewish liturgy in community settings alongside non-Jewish choirs. Whether Jewish singers are part of a choir or a congregation, or even a congregation that effectively becomes its own choir, their participatory–and often harmonic–sound shapes both the aesthetic and the self-conception of British Reform worship. The deliberate focus on communal liturgical song rather than prayer led by a privileged solo singing voice helps to mark the congregation as British as well as Jewish.

This essay is grounded in ethnographic participant-observation work that I conducted in the United Kingdom between 2014 and 2017. During this time, I attended worship services at congregations both in London and elsewhere in Britain, and interviewed congregants and clergy about how they perceived the role of music in worship. I sang as a member of the Kol Echad choir in Cambridge and attended workshops and music fairs sponsored by the MRJ and the Zemel Choir of London. I begin my argument with a discussion of the roles that choral and congregational song play in British Reform synagogues. While congregations do draw distinctions between these two forms of group song, in practice the distinctions are not as clear-cut as they might appear at first glance. Following this discussion, I examine the codification of group song in synagogues through the 1899 “Blue Book” and the MRJ’s 2012 publication Shirei Ha-T’fillot (“Songs of Prayer”). I explore instances of group song in other British cultural venues, establishing the larger culture of group song of which British Reform Jews are a part.

I then discuss in detail two Reform congregations, Beth Shalom in Cambridge and FRS in London. In many ways, these two congregations are very different from each other in the style, language, and formality of their worship. Beth Shalom takes a relatively conservative approach to ritual, and chooses not to have any clergy in a formal position of leadership. By contrast, FRS is known for its highly liberal, American-influenced worship aesthetic, and employs three rabbis and one cantor to lead its services. Being so different from each other in their worship and leadership practices, Beth Shalom and FRS can be said to represent the breadth of variation in practice among British Reform synagogues. However, their approaches to group song and the relationships between the congregations and the choirs associated with them are surprisingly similar.

While many scholars, primarily historians and sociologists, have written about the position of British Jews as a minority within an increasingly multicultural society, relatively little attention has been paid to the cultural context of British Judaism, and the ways in which British Jews negotiate both halves of this dual identity. British Reform Jews do not live in isolation from their surrounding culture; indeed, they are so well integrated into British cultural life that the sharp increase in antisemitism from the Labour Party that began in 2015 caused shock and surprise as well as anger in Jewish Labour supporters. The musical performance of progressive Anglo-Judaism is marked by creative adaptation. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, both Jewish and non-Jewish composers working for Reform congregations incorporated elements of the British sacred choral tradition into new vocal music for Jewish worship. Contemporary British Reform communities take note of contemporary trends in progressive Jewish music coming from the United States and Israel, and adapt them to meet the needs of British Reform liturgy. Additionally, a few Anglo-Jewish composers are creating new works designed explicitly to suit British Reform tastes for group liturgical singing.

The Voices of Congregation and Choir

Choirs have been an important source of collective song in British synagogues since the middle of the nineteenth century. David M. Davis (c. 1853 – 1932) led some of the first synagogue choirs in the country, at the Orthodox East London, New West End, and St. John’s Wood Synagogues, between roughly 1875 and 1925 (Rubinstein and Jolles 2011:201). Additionally, Hampstead Synagogue debuted a mixed-voice (SATB) choir in 1892 (Chernett 2010). As Reform Judaism gained strength in the twentieth century, many Reform synagogues also employed choirs. The choral tradition in British Reform synagogues reached its peak in the middle of the century. Although choirs have declined in popularity during the 1970s and 1980s, some Reform synagogues still employ them, either regularly for Sabbath services or for special occasions. In addition to synagogue choirs, several Jewish choral societies perform liturgical music as concert repertoire. These include the Zemel Choir and the London Jewish Male Choir–both based in London–and Kol Echad, based in Cambridge. Such choirs often perform their repertoire at concerts hosted in synagogue buildings, whether or not the choir “belongs” to that synagogue.

However, as important as choral singing is to the sound of Anglo-Jewish prayer, it is not the only form of group song practiced in Reform synagogues. For many Reform congregations, the performative sound of the choir is less important than the participatory sound of congregational singing. Rabbi Dr. Barbara Borts traces this shift to the 1960s, when the Reform Synagogues of Great Britain (RSGB), the precursor to the MRJ, turned its attention to the performance of synagogue music. An RSGB sub-committee on music attempted to disseminate choral music to Reform synagogue choirs, but the notation did not always lead to beautiful choral singing. As Borts observes, the music:

. . . had also taken on the patina of folk song, in that it was often transmitted aurally to choristers who may or may not have read music, and who, in turn, transmitted the music to newer synagogues. As melodies were not always practised from the original, or even a written score, they were sometimes recalled inaccurately. (Borts 2020:58)

By the time the RSGB decided to compile a siddur, or prayer book, of its own in 1977, its leaders wished to move away from European-style classical music and reclaim a sense of agency for the congregation as well as a somewhat nebulous concept of “Jewishness.” Philip Roth of Edgware and Hendon Reform Synagogue in London recalls that the synagogue’s choir ceased to sing at full strength for Friday night services in the 1980s.

They wanted to make the service more participatory and less choral. More chanting, that sort of thing. And there just wasn’t the need for a choir. So we decided, we don’t really need a choir. For a while, we did just do it as a quartet rather than a full choir. And we had sort of two quartets that used to do it on alternate weeks (Roth 2016).

Borts suggests that this moment “is perhaps the beginning of the desire for ‘authenticity,’ a wish to incorporate the music most associated with Jewishness, that of the Yiddish worlds” (Borts 2020: 60). Because of this increasing association between concepts of “Jewishness” and “authenticity,” and the largely monophonic Yiddish table songs of Eastern Europe, congregational interest in synagogue choirs began to decline shortly after the release of the new siddur. As Jonathan Friedmann has observed, this movement toward simpler and more participatory music took place in the same decade as a similar movement among liberal American synagogues that drew on the musical repertoires of the Reform and Conservative youth movements (Friedmann 2012:77). Indeed, as the RSGB and congregants themselves took a new interest in more broadly accessible melodies, they imported a few newly-composed melodies by American composers including Jeff Klepper and Debbie Friedman (Borts 2020:64).

Today, rabbis, cantors, lay leaders, and musicians serving Reform synagogues work to bring music directly to congregants. Many of the workshops at the biennial Shirei Chagigah festival of Jewish music and learning involve teachers demonstrating new music to interested participants and offering tips and techniques for teaching music to congregations and encouraging them to sing with confidence during worship. Some synagogue musicians even compose new liturgical music that can perform double duty, featuring melodies and simple harmonies appropriate for congregational singing, in addition to full choral arrangements for those congregations that employ choirs. In a demonstration workshop at the 2015 Limmud festival in Birmingham, composer Joseph Finlay announced that the audience would “hear tonight my attempts to find a Jewish synagogue sound which is fun, participatory, but also sort of true to me.” Finlay explained that the demonstration was to be understood as a workshop rather than a concert, adding “the point is probably to learn some more melodies that you can take home to your synagogues” (Finlay 2015).

Because of a distinct lack of professional musical leadership in contemporary MRJ synagogues this kind of lay musical transmission works relatively slowly but, as I describe later in this essay, synagogue congregations do learn new melodies from each other. However, a great deal of synagogue repertoire, as well as the aesthetic that still exercises significant influence over congregational musical taste, comes from two collections of synagogue music, published over a century apart. The 1899 “Blue Book” and the 2012 Shirei Ha-T’fillot represent two different styles of liturgical music, and take opposing approaches to presenting it. Nonetheless, both publications focus on and promote the idea that group song, whether choral or congregational, is the sound of a British synagogue.

The Blue Book and Shirei Ha-T’fillot

Although it is formally associated with the United Synagogue and Orthodox worship, Kol Rinnah U-Todah (“The Voice of Prayer and Praise”), affects the musical lives of Reform congregations as well. Rabbi Francis Lyon Cohen (1862 – 1934), then the rabbi of Borough Synagogue in London, and David M. Davis, at that time the choirmaster of the New West End Synagogue, compiled the book at the request of the Choir Committee of the Council of the United Synagogue. Cohen and Davis had previously collaborated on an earlier collection of liturgical music entitled Shire Keneset Yisrael: The Handbook of Synagogue Music for Congregational Singing (“Songs of the Community of Israel”), published in 1889.

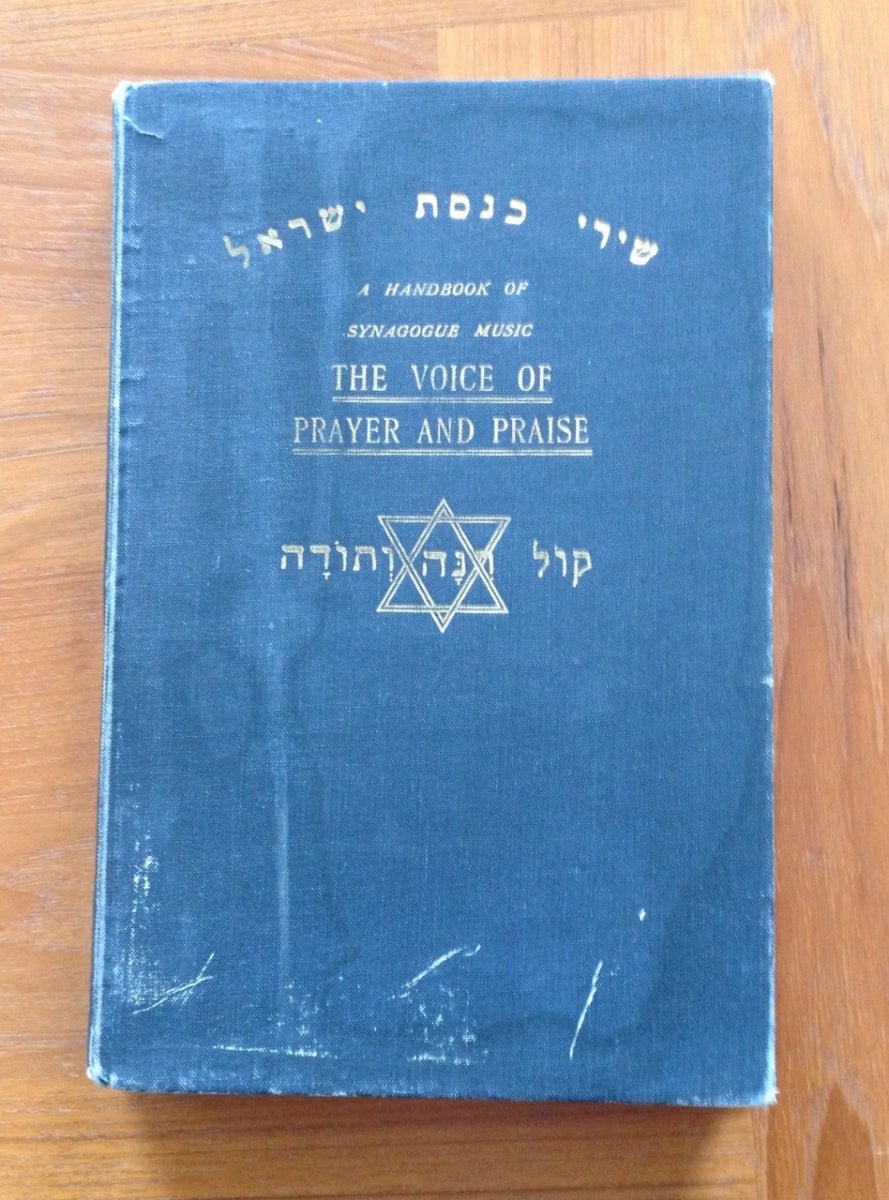

Figure 1. The cover of Kol Rinnah U-Todah (“The Voice of Prayer and Praise”), commonly called the Blue Book. Photograph by author.

Danielle Padley observes that this collection did interest at least twenty synagogues, although it would soon fade out of regular use (Padley 2019:10). Cohen and Davis re-edited and re-published this book in 1899 as Kol Rinnah U-Todah, the version remembered and used today. Known informally as the “Blue Book” for its blue cover (see Figure 1), the book contains multiple settings of common synagogue prayers, drawn from composers adhering to both the Orthodox and Reform traditions. Its stated purpose is to encourage group harmony singing in Anglo-Jewish worship; in the 1948 Preface to the reprinted Third Edition

Attention is drawn to the fact that this volume is not merely one for the Choirmaster and his choristers. It is essentially ‘A Handbook of Synagogue Music for Congregational Singing,’ and an aid to worshippers to participate chorally in the Religious Services, and not simply to listen to a Choir. (Cohen and Davis 1899:viiib)

Musicologist Alexander Knapp suggests that part of the reason that Cohen and Davis wished to encourage congregational singing was to “reduce congregational acceleration through the prayers by providing for them to be sung together rather than having them merely read” (Knapp 1996 – 1998:183). To this end, the Blue Book features both longer prayer texts and shorter congregational responses printed in hymnal-like grand staff notation, with the texts transliterated into the Roman alphabet. The book is compact enough that a congregant could hold it easily and sing along with other congregants following the notation and the transliterated text. Slowing the congregation’s movement through prayer texts by means of communal singing would help them to advance through the liturgy together and might also help them to focus on the intentionality of their prayer.

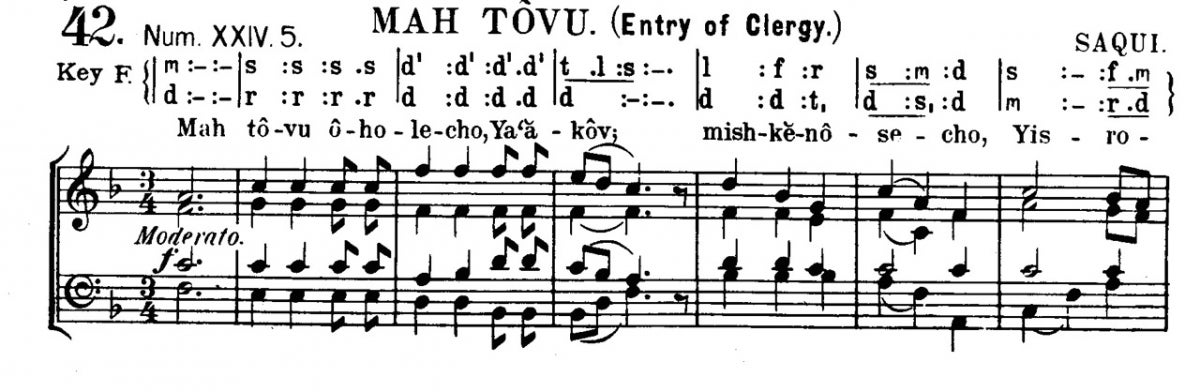

Figure 2. A selection from the Blue Book, showing tonic sol-fa notation above the grand staff. Cohen and Davis 1899:28.

In addition to the staff notation, the Blue Book also features tonic sol-fa notation for the soprano and alto lines above the grand staff (see Figure 2). Tonic sol-fa notation consists of letters representing the degrees of the Western scale (do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti) and punctuation marks, including colons, dashes, and vertical bars, to indicate measures, beats, and note values. This has been a part of the Blue Book since its original publication. The 1899 Preface makes its purpose clear.

Remembering the extent to which our choir-boys and the pupils of Religion Classes are drawn from Elementary Schools, the Editors have presented the Soprano and Alto parts in the Tonic Sol-fa as well as in the Staff Notation. (Cohen and Davis 1899:vi)

Cohen and Davis included tonic sol-fa notation in order to enable the broadest possible group participation in the music of the synagogue. Its presence, explicitly stated to be for children, indicates the degree to which British Jews were integrated into larger British culture.

Tonic sol-fa notation was formalized in the middle of the nineteenth century by the educator John Curwen (1816 – 1880), who based his system on an earlier system of hand gestures developed by Sarah Glover (1785 – 1867), a teacher who lived in Norwich (McGuire 2009:17; see also Bennett 1984:57). Tonic sol-fa notation was cheap to produce and easy to teach, and Curwen published several instructional manuals and songbooks using the system. The English Education Department officially recognized it in 1860, and English primary schools adopted the system in the 1880s and 1890s (Russell 1987:30; see also McGuire 2009:24). By the turn of the twentieth century, British Jews of all social classes enrolled their children in local state schools, where they received the same education as other children, including instruction in choral singing from tonic sol-fa notation. The songbooks used in schools contained a mixture of English folk songs and simple Christian hymns. However, on the Sabbath, Jewish schoolchildren who attended services at synagogues that used the Blue Book could apply the musical skills that they had learned in school to Jewish liturgy and hymnody. The social movement associated with tonic sol-fa singing was evangelical and Nonconformist. It promoted the idea of learning music and singing in large choirs as a form of social and moral uplift, along with temperance and missionary work (Wright 2012:173; see also Russell 1987:26). Whether out of choice or by necessity, Anglo-Jewish families aligned themselves with this particular working-class group musical movement, and then elected to adopt it into their own musical culture.

Although the Blue Book was a project of the Orthodox United Synagogue, it had, and continues to have, a significant impact on Reform congregations as well. Some of this impact comes from Reform congregants who moved into Reform from Orthodoxy. Sheila Levy of Beth Shalom in Cambridge recalled that the music she heard growing up Orthodox in Liverpool was “very much from the Blue Book” (Levy 2015). Levy retains her love of the Blue Book today and uses melodies from that source when she takes a turn leading services at Beth Shalom. Reform synagogues that are older and more established than Beth Shalom draw from the Blue Book as well. Danielle Padley told me that, at Edgware and Hendon Reform Synagogue in London, “We use the Blue Book quite a lot, not exclusively,” observing that the choir director programs music from the Blue Book often enough that the choir knows her code for it. “She’ll just go 263, and we know that that’s page 263 of the Blue Book, which is Havu L’Adonai. You get to know it by that” (Padley 2015). The Blue Book’s impact on Anglo-Jewish life is so powerful that, when Cantor Zöe Jacobs described the production of the Movement for Reform Judaism’s music compilation, Shirei Ha-T’fillot, she recalled that “we were talking about it for a while as being the Reform Blue Book” (Jacobs 2015).

Both the Blue Book and Shirei Ha-T’fillot feature a significant amount of music intended for group harmony singing. Much of this music is by British composers. David M. Davis either composed or arranged many of the selections in the Blue Book. Several composers whose music shaped the sonic space of British synagogues are represented in the Blue Book as well. Among them are Julius Israel Lazarus Mombach (1813 – 1880), the choirmaster of the Great Synagogue in London from 1840 until his death, the pianist and composer Charles Salaman (1814 – 1901), and Abraham Saqui (c. 1824 – 1893), the first choirmaster of the Liverpool Old Hebrew Congregation on Princes Road.

Similarly, Shirei Ha-T’fillot features contemporary British composers of Jewish music, including the singer-songwriter Judith Silver, professor of composition at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London, Malcolm Singer, composer Julian Dawes, and composer Joseph Finlay, the former musical director of Hendon Reform Synagogue in London, and current director of the London Jewish Male Choir. The book includes a range of opportunities for harmony singing. For congregations with choirs, or performance groups, the editors sought out a variety of choral music. There are also several canons that allow non-choral congregations to sing in harmony as well. The ethos behind the collection of Shirei Ha-T’fillot is one of inclusivity. In her introduction to the compilation, Rabbi Sybil Sheridan writes that

The focus has shifted from passive appreciation to full participation. Spirituality is perceived less in the beauty of words and melody performed than in the beauty of words and melody recited and sung in community and with gusto. (Sheridan 2012:1)

It is in the spirit of encouraging the widest range of participation possible that Shirei Ha-T’fillot includes multiple settings of texts. Some settings are simple unison lines that can be sung as congregational chants, or in canon. Some settings are more complicated, in order to offer a greater musical challenge (Sheridan 2012:3). There are melodies with short call-and-response sections, and melodies in which a cantor or a songleader involves the congregation in a longer dialogue. Throughout the book, Sheridan and her co-compilers emphasize group song and provide several options so that both highly musical and less musically confident congregations may have the opportunity to sing.

Group Song in the United Kingdom

This emphasis on group song in the British Reform tradition stems partly from the fact that full-time cantors are relatively rare in this movement. At present, only a few Reform congregations in the UK employ full-time cantors. Cantor Zöe Jacobs has worked at Finchley Reform Synagogue since 2009, and Radlett Reform Synagogue hired Cantor Sarah Grabiner in 2019. Cantor Cheryl Wunch worked at Alyth, also in London, in 2014 and 2015. And most recently, Cantor Tamara Wolfson joined Alyth in 2020. All four are graduates of what is now the Debbie Friedman School of Sacred Music at Hebrew Union College in New York City. This relative scarcity of full-time, professionally trained cantors is a situation that is likely to continue, as there is no accredited cantorial school in the UK. Although informal training networks exist, especially through the Masorti movement’s Skype-based European Academy for Jewish Liturgy, accredited, professional cantorial training must still be undertaken overseas, in the United States or in Israel, and thus remains a difficult undertaking for aspiring British Reform cantors. Other synagogues may employ part-time lay cantors, many of whom may have trained informally or via apprenticeship.

In the absence of cantors, a congregation’s music director, sometimes assisted by a choir, has often assumed the role of leading the liturgy in British Reform congregations. As Jewish Reform movements sprang up in Western and Central Europe and in the United States, the Reformers attempted to modernize Jewish worship and bring religious practices into line with the aesthetics and social rhythms of the local community. In a post-Emancipation society, this type of worship reform might help congregants integrate into society beyond a ghetto. Most of the Reform movements shortened the liturgy, adjusted the start time of services, allowed certain prayers to be said in the vernacular rather than in Hebrew, and introduced a sermon into the Sabbath morning service (Endelman 2002:95). In Britain, both Orthodox and Reform synagogues adopted a set of ritual reforms that borrowed both form and vocabulary from the Church of England. Michael Myer observes that, by the middle of the nineteenth century, both British Reform and Orthodox synagogues used words such as “vestry” and “wardens” to describe the architecture and functionaries of synagogues, the latter wearing clerical gowns along with rabbis (Myer 1988:178). Sharman Kadish describes this aesthetic, especially in Orthodox synagogues, as “traditional Jewish content dressed up in English packaging,” drawing particular attention to top hats and dog collars worn by clergy (Kadish 2002:393). At the West London Synagogue today, the wardens still wear top hats as a symbol of their role in ensuring that the service runs smoothly.

During the middle of the nineteenth century, British synagogues adopted the choir at roughly the same time as the Anglican Church revived the institution. Nicholas Temperley describes the institution of the modern Anglican church choir, featuring choirboys set apart from the rest of the congregation, wearing robes and singing in harmony as the congregation listens, as the result of an Anglican revival that began in the 1830s. Church leaders debated the form that worship music should take, eventually instituting robed choirs around 1850. Temperley cites the rise of the middle class and the allure of elegance and grandeur as motivations, observing that

In a period of great social mobility, the new and growing middle-class public was anxiously looking for symbols of its new status. It turned its back on both rural traditions and the industrial society that supported it. Hence there was great appeal in the paid, semi-professional, robed parish church choir, singing cultivated liturgical music which was in sharp contrast with the congregational hymnody of dissenting chapels, and which approached the aristocratic dignity of cathedrals. (Temperley 1979:277)

The most famous of these choirs is the all-male King’s College Choir from Cambridge. The soprano and alto lines are sung by boys, most of whom attend the nearby King’s College School, and who give the choir what Leo Samama describes as “a crystal-clear, slightly sharp, but extremely well-projected choral sound” (Samama 2012:99). These institutions are the model for a choral infrastructure that encompasses both religious and educational choirs, very few of them permanent professional organizations (Samama 2012:98). In addition to the ancient universities, roughly fifty other Anglican cathedral schools provide selected students with choral scholarships, which can pay up to £1,500 per year, in exchange for singing in the choir. While some single-sex choirs remain in university colleges and cathedrals, many churches employ mixed-voice, SATB choirs made up of men and women.

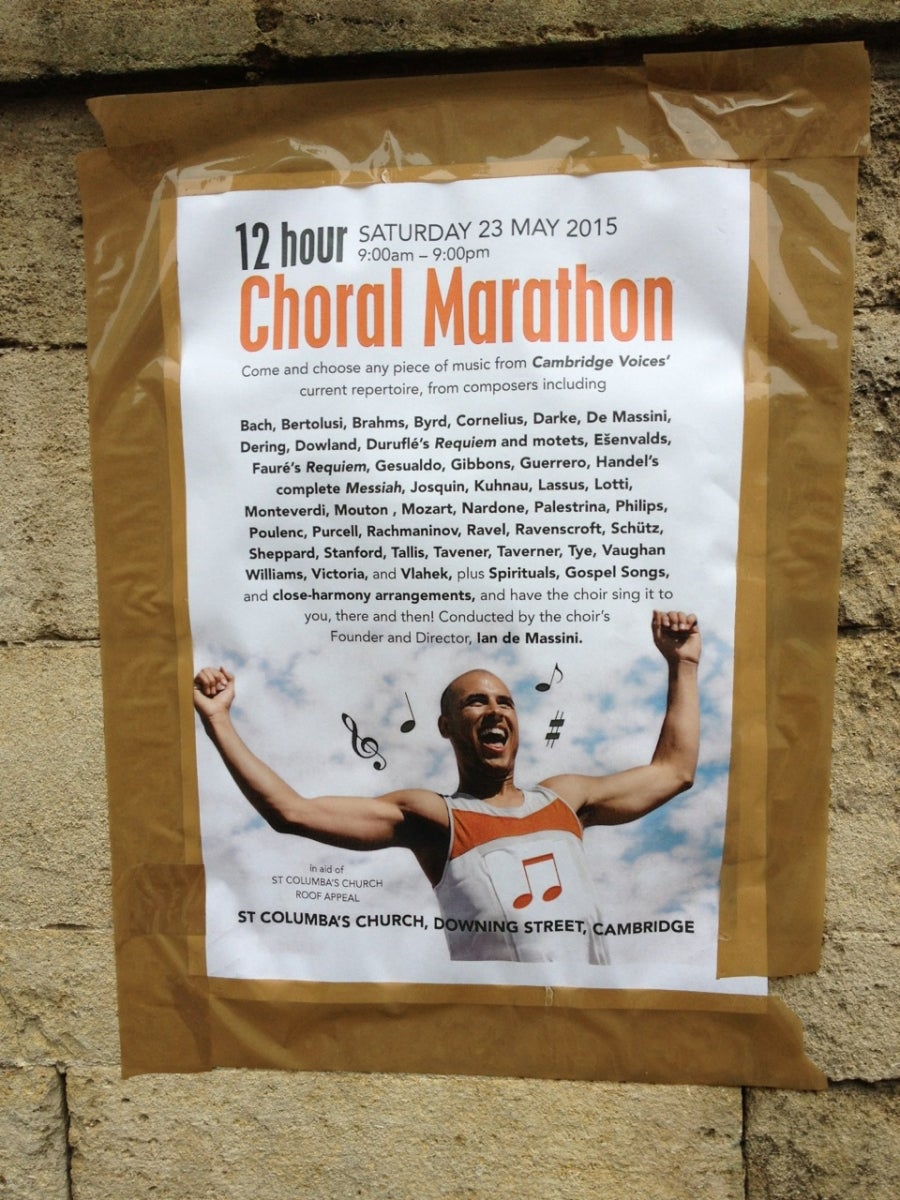

Figure 3. A poster advertising the twelve-hour choral marathon to raise money to repair the roof of St. Columba’s church in Cambridge. Photo by author.

Even largely independent concert choirs can maintain intimate relationships with churches and their congregations, as their directors may also hold jobs as church musicians. The choir Cambridge Voices performs under the baton of its founder, Ian de Massini, who is also the Director of Music at St. Columba’s United Reform Church in Cambridge. On May 23, 2015, Cambridge Voices held a twelve-hour choral marathon to help raise funds for the repair of the church’s roof (see Figure 3). The choir invited passersby to stop in and select any piece of music from the choir’s significant classical and sacred repertoire, which the choir would sing. Donation boxes placed near the repertoire lists encouraged listeners to support the church’s appeal for roof repair. A church might also host choirs performing for charity. On December 12, 2016, Little St. Mary’s Church in Cambridge invited local choirs to raise money for Red Balloon, a charity that helps children who cannot attend school because of bullying. Some choirs were associated with local churches, while others came from Cambridge colleges and local schools. The Jewish choir Kol Echad also received an invitation and contributed two pieces to the concert.

Communal singing plays a significant part in British popular culture as well. Outside of religious and academic institutions, choral and other group singing remains a popular leisure activity in the UK. Although the organized choral movements of the 1840s intensified and codified British choral activity, the tradition of working-class choral singing was established long before then, especially in Yorkshire and Lancashire in England (Russell 1987:23). The tradition of popular choral singing is especially powerful in Wales. Following the 1966 Aberfan Mine Disaster, members of the coal tip removal committee found themselves in need of social and emotional support. They formed the Ynysowen Male Voice Choir, which continues to meet and perform into the present day. The choir’s website explains that the original mandate of the choir was to “perform for charity, to give thanks to everybody who had contributed to the disaster fund that had been set up during the time of the Aberfan tragedy” (Ynysowen Male Voice Choir 2018). In less emotionally charged circumstances, a charity might decide to sponsor a singalong performance of a large choral work from the Western classical canon, and booklets of Christmas carols might be passed around at an informal holiday gathering. Denise Neapolitan, a fiddler living in Cambridge, describes pub music sessions she has attended in the UK and in Ireland.

The singer will usually start it off, often accompanying himself on guitar, sometimes a cappella. And then, gradually, other musicians will join in, either with the musical instruments or harmonizing. A lot of folk songs have a certain kind of call and response to them, too. So you’ll have people joining in on that or joining in on the choruses mostly. (Neapolitan 2015)

Choirs also maintain a visible and audible presence in sports and reality television programming. Since 1927, the FA Cup Final has included a rendition of the hymn “Abide With Me.” This tradition has proved popular enough that, at the 2015 Final, the hymn was led by a choir made up of sixty-four fans of the teams that progressed to the third round of competition. A BBC television program called Songs of Praise sponsored the choir and hosted a competition for the privilege of participating (Stone 2015). A similar fan choir sang the hymn to open the competition in 2018 as well (Standard Sport 2018). In 2006, the BBC engaged choir director Gareth Malone to host a reality show called “The Choir.” Several variations of the show aired between 2006 and 2016. In each variation, Malone teaches the art of choral singing to a group of people who have never had the opportunity to participate, including the pupils of a comprehensive school in Middlesex, the residents of a working-class housing estate in Watford, and a group of military wives and girlfriends living on two British Army bases in Devon. Malone himself has received royal recognition for his services to music, and the BBC supplies lists of choirs and resources for workplaces and organizations wishing to institute their own choirs similar to those that have appeared on Malone’s show (BBC 2020). Similarly, in 2008, the BBC aired a second choral-themed reality show, “Last Choir Standing.” This show functioned as a competition among amateur choirs, of whom roughly one thousand entered the initial, pre-taping rounds of competition (BBC 2020B). And when the political action group Citizens UK held a pre-election rally on May 4, 2015, nearly half of the total program was devoted to performances by a school orchestra and local singing groups, including one group made up of singers from FRS, led by Cantor Jacobs.

In the world of community and leisure choirs, a singer’s ability to read music does not necessarily present a barrier to participation. While the ability to read musical notation is an advantage if one wishes to sing in either a religious or a leisure choir, it is not a requirement for participating in many such groups in the UK, much as the tonic sol-fa movement had hoped. Those singers who do not read musical notation at all learn their parts by ear from the singers around them. Some singers who learned to read tonic sol-fa, but who are not necessarily adept at reading staff notation find ways to translate their parts into tonic sol-fa in order to learn them. Ruth Bender Atik of Leeds recalls singing in a synagogue choir as a teenager in the 1960s:

Quite a lot of the choristers, even at that time, apart from knowing tonic sol-fa, also couldn’t read music. So a lot of it was by ear. For example, I went to sing alto after a while, and I moved from the sopranos to the altos. And you just had to sing what the person next to you was singing. (Bender Atik 2015)

One notable side effect of this oral transmission of polyphony is that a single piece of music may develop many variations in its harmony, according to the vagaries of the singers’ memories. It is notable that many British leisure choirs, as well as the choirs of some minority religious traditions, such as Reform Judaism, place more value on the presence of harmony than on the strict adherence to the specific harmony of the printed page.

Although it was born in the nineteenth century, when the West London Synagogue officially declared itself Reform shortly after its consecration in 1842, the British Reform movement came into its own in the middle of the twentieth century. Synagogues were founded in an environment where the predominant local worship tradition involved choirs and congregational hymn singing. Outside of the synagogue, choral societies, pub singing, and other group vocal events formed an integral part of local social life. In a culture where school children could earn money for choral singing, community choirs offered opportunities to get out of the house and socialize with the neighbors, and hymn singing formed part of the pageantry of sports. Overall, British Reform Jews encountered and participated in group song from an early age. In the absence of the charismatic, operatic cantors who drew crowds to American synagogues, the music of British Reform took on a communal, multi-voiced character.

Harmony singing is an important part of this worship aesthetic. It does require some form of leadership, and as a result, the line between choral music and congregational music has become blurred, with both forms of synagogue song existing on a spectrum rather than as separate entities. Some synagogues have formal choirs, seated apart from the congregation, that sing in harmony as the congregation listens; this is the role of the choir at the West London Synagogue. There are also synagogues in which the congregation sings entirely on its own, as is the case with Beth Shalom in Cambridge. However, the division has never been absolute. Danielle Padley observes that organist and choir director Charles Garland Verrinder (1839 – 1904) hosted rehearsals at WLS for interested congregants as well as for the choir, “a measure to ensure decorum during services whilst promoting congregational participation” (Padley and Wollenberg 2020:179). Some contemporary synagogue choirs, such as the choir of Edgware and Hendon Reform Synagogue, wear ordinary clothing, and may sit very close to the congregation, thus encouraging congregants to sing with them for parts of the service. At other synagogues, such as Bromley Reform Synagogue, the “choir” consists of a small number of congregants (roughly six to eight) who get together to practice the music of the liturgy and sit together to take on an informal leadership role during the service. Finally, as I discuss later in this essay, Cantor Zöe Jacobs of Finchley Reform Synagogue prepares interested congregants to sing the music she has chosen for that week and scatters them throughout the congregation, providing musical support without the formality of a choir. This practice is similar to one that Marsha Bryan Edelman describes in synagogues in the United States, “creating the illusion that these singers are just ‘regular members of the congregation,’ extemporaneously harmonizing, rather than devoted amateurs who have spent hours to master their parts” (Edelman 2021:41). While the organization of the dispersed singers at FRS is less formal than what Edelman describes, the effect is similar.

Even if not all British Reform congregants are musically literate or members of an official choir, they appreciate and value harmony singing as a part of worship. The harmony may take the form of a round or canon structure, or there may be an accepted descant to accompany a melody, or there may be enough congregants who are familiar with a work to sing harmony parts as a composer or an arranger wrote them down. Ruth Bender Atik recalled absorbing harmony from a young age listening to the choir at the Liverpool Old Hebrew Congregation.

The clergy had accepted a mixed choir from sometime around wartime, when a lot of men were called up. Women and small boys, I guess, did most of the singing. So I used to listen to it. I used to love harmony, and I used to hum along. And then when I was about fourteen, I met somebody through my parents. And I said I’d love to sing in the choir, and they said okay. (Bender Atik 2015)

Even if congregants do not know the “official” harmony of a piece, they may improvise. Many British Reform congregants are familiar with Louis Lewandowski’s setting of the last verses of Psalm 92, “Tzaddik Katamar.”[1] Whether or not a given congregation knows the exact harmony lines that Lewandowski composed, congregants will often add their own harmonies to the familiar melody, approximating both Lewandowski’s harmonic structure and a two-part canon passage that appears in the second half of the piece. Other congregants may have learned harmony parts from service in other choirs, allowing younger congregants to pick up the harmonies by sitting next to them and listening. Some congregations may choose an even simpler form of harmony, singing in parallel thirds. Bender Atik explained how her current Reform congregation, Sinai Synagogue in Leeds, approaches harmony singing.

There was always a feeling that as long as you were within the chord, you were okay. And that’s still the case, because if you don’t have a tenor that week, and you don’t happen to have the music, well, you’ll fill in what you think would pretty much be the tenor line. (Bender Atik 2015)

Bender Atik also stated that the minimum requirements for harmony, as she sees them, consist of a melody line and the third. “It has to be the third.” Even in congregations that are less musically inclined than others, there is a sense that group singing is important, whether it comes from a choir or from the congregation, and that some form of harmony is preferable to unison song.

Case Studies

I now describe some of the ways in which this aesthetic of communal song might appear in worship services. I take as my examples Beth Shalom, the Reform community in Cambridge, and Finchley Reform Synagogue in London. Although they are both part of the Movement for Reform Judaism, these two congregations are quite different in character, in size, and in their approach to ritual and leadership. Their similarities lie in the realm of music. Both congregations are highly musical, and both place great value on group song.

Beth Shalom Reform Synagogue in Cambridge is the only Reform congregation in East Anglia. It began in 1976 as an offshoot of the Cambridge Jewish Residents’ Association. By 1981, the synagogue was officially constituted, according to its Articles of Association, as Beth Shalom Reform Synagogue. The Articles state that “The ritual to be used at services shall conform to the practices of the Movement for Reform Judaism of Great Britain.”[2] As the congregation grew, it occupied a series of spaces in local churches and schools. On June 11, 2015, it moved into its own building. The congregation has never had a full-time rabbi or cantor, although founding member Michael Gait told me about occasional services led over the years by a series of students and student rabbis, including Rabbi Sybil Sheridan–then a student at Girton College. Beth Shalom continues its lay-led tradition today, with congregants taking turns to lead services.

Music, and specifically group song, have been part of Beth Shalom’s tradition since its founding. The congregation chooses not to use instruments in worship services. All of the music in worship is sung a cappella by the congregation. In its early years, Beth Shalom had a music director named May Daniels, who attempted to organize a formal choir. The records of the synagogue’s Ritual Committee from the 1980s include an ongoing series of reports from Daniels in which she details her efforts to establish and improve Beth Shalom’s music. She writes in 1982 that “I have been visiting Reform and Liberal Synagogues in London to observe their liturgy and music with a view to learning what might help to enrich our own practice,” and observes that “The singing at the first HH [High Holy Days – RA] services of Beth Shalom was spontaneously praised by many of the congregants.”[3]

Daniels’s formal synagogue choir was not popular enough to survive and was disbanded in the early 1990s. In its place, the congregation at Beth Shalom carries the entirety of the music of the service. Members support each other vocally, and those who have joined Beth Shalom from other communities bring new melodies and new harmonies to Beth Shalom. A typical Shabbat morning service at Beth Shalom includes well-known melodies by Mombach, Lewandowski, Salomon Sulzer, and Shlomo Carlebach, some nusach–the ancient musical formulas for Jewish prayer, in the Western Ashkenazi tradition–and perhaps a tune or two that is a particular favorite of the congregant leading services that week. Because many of Beth Shalom’s congregants originally came from other communities, and because so many of them have contributed favorite tunes to Beth Shalom, the congregation’s repertoire is surprisingly large. Lay service leaders do not hesitate to demonstrate new melodies, confident that there are enough strong singers present at most Shabbat services that the congregation as a whole can learn new music within a few months, as happened when a lay leader introduced Meir Finkelstein’s setting of “L’Dor Vador” (“From Generation to Generation”) in 2016. Musically confident congregants provide harmony lines, and newcomers learn Beth Shalom’s repertoire by ear.

Although Beth Shalom does not have a formal synagogue choir, it maintains a relationship with Kol Echad, Cambridge’s Jewish community choir. The current incarnation of Kol Echad was formed around the year 2000 (Levy 2015). It is open to anyone who wishes to join, regardless of religious affiliation; not all of its members are Jewish. It functions as a concert choir for the Jewish community of Cambridge and the surrounding area, and appears regularly at events sponsored by the pan-denominational Cambridge Jewish Residents’ Association, including annual Chanukah and Yom Ha-Atzma’ut (Israeli Independence Day) parties. Many of the members of Kol Echad also attend services at Beth Shalom, and the choir has rehearsal space in Beth Shalom’s building. For several years prior to and during the building’s construction, Beth Shalom engaged Kol Echad to sing at fundraising concerts for the building project. In addition, Kol Echad has visited Beth Shalom to sing on special occasions. The choir is often present at the annual service on Yom Ha-Shoah, the Jewish day of remembering the Holocaust, and it made a special appearance in 2017 leading the morning service on Shabbat Shirah–the “Sabbath of Song–when the Torah portion containing the Song of the Sea (Exodus 15:1 – 18) is read. However, a majority of members of both of these groups do not want to make their relationship any closer. Michael Gait told me that Kol Echad “should never be thought of as the choir of the synagogue, ever!” adding that “the tradition of everybody singing should be kept up” (Gait 2015, emphasis added). Sheila Levy concurred, recalling her childhood in a synagogue with a choir and very little congregational participation, saying “I don’t want that for Beth Shalom. I think the participation is very important for it” (Levy 2015).

Music is similarly important in the life of Finchley Reform Synagogue (FRS) in London, although the character of the services and the music is rather different. FRS was founded in 1960 as the Woodside Park and District Reform Synagogue, and has been formally affiliated with the Reform movement since 1962. Its repertoire encompasses contemporary American folk-style worship music and contemporary choral composition as well as older melodies by Mombach, Sulzer, and Lewandowski and a small amount of Western Ashkenazi nusach. In 2009, FRS hired Zöe Jacobs to serve as the first Reform cantor in the UK. In collaboration with Rabbi Miriam Berger and choir director Mich Sampson, Jacobs has overseen the development of a strong and varied musical life at FRS. Having a full-time professional cantor is unusual for a British Reform synagogue, and Jacobs functions as a musical leader rather than a solo representative; worship at FRS still focuses on the sound of group song.

In addition to congregational song and Jacobs’s cantorial work, FRS maintains a small formal choir under the direction of Mich Sampson. Like many British Reform synagogues, FRS disbanded an earlier version of its choir in the 1980s. Jacobs recalls that, at the time, the congregants of FRS “were falling out of love a little bit with the music of the liturgy.” Because of this, the choir became less popular at FRS. “They were not doing what the community wanted them to be doing, and so after a while, they were sort of almost ruled out. They were allowed to sing on the High Holy Days, and even that sort of felt like a bit of the challenge for the community” (Jacobs 2015). However, since Jacobs received her ordination in 2009, she and Sampson have worked to return the choir to FRS, although in a different format that recognizes the congregation’s desire to participate in worship as well.

Sampson began to lead the High Holy Days choir in 2012, and under her leadership, its sound improved, and FRS congregants rekindled their interest in hearing it. Following the High Holy Days in 2014, Sampson and Jacobs decided to bring back a modified Shabbat choir as well. Jacobs notes that the choir does not sing for every Shabbat, “because we decided the community might have quite a strong feeling about that.” Instead, they sing as a full choir only rarely, but spend the rest of the time enhancing worship in other ways. Jacobs says, “what that means is, there’s a gorgeous group of people who sing beautifully, who contribute to the congregational voice, and just build the sound. And that sounds really quite amazing” (Jacobs 2015). As a result, the congregants of FRS come to the worship service far more musically confident than they might have been without Sampson and Jacobs’s curated coaching.

As at Beth Shalom, the congregation of FRS participates fully in creating the music of worship. Even if Cantor Jacobs and Rabbi Berger are playing guitars and using microphones, congregants join in with great enthusiasm, singing in harmony, and often joining in on parts of the liturgy traditionally reserved for the service leader. At one Friday evening service, a portion of the congregants sang the call to prayer along with Jacobs, an act that is not part of the formal order of service, in which the service leader sings the call to prayer alone, followed by a congregational response; the next morning, one woman observed, half-jokingly, that Jacobs had tacitly encouraged them to do so by saying “Let’s call each other to prayer.”

Indeed, Jacobs works deliberately to cultivate and nurture a culture of group song at FRS. Once a month, she holds a music session called Shira, the Hebrew word for “song.” Shira takes place in the hour before the normal Shabbat morning service begins. It is a time when interested members of the congregation can come together with Jacobs to sing, and to learn new music and new harmonies, some of which may appear later that morning in the service. Shira is an entirely voluntary event, and does not necessarily draw all of the same people for each session. The congregants who do attend Shira support and strengthen the rest of the congregation during the regular Shabbat service, and they also serve as support for Jacobs when she chooses to introduce a new composition into worship.

Conclusions

Although their worship services differ greatly from each other in style, Beth Shalom and Finchley Reform Synagogue share both a reverence for music and a sense of what the music of worship should sound like. Beth Shalom combines a conservative approach to ritual and extensive use of Hebrew in its prayers with a strong appreciation for do-it-yourself (DIY) music-making. Worship at FRS is much more contemporary and liberal in style. Here, we hear the use of shorter prayers and more English than one would find at Beth Shalom, and its music is made with a certain amount of formal leadership. However, both of these synagogues demonstrate a commitment to group song, and specifically to multi-voiced group song, that marks them as part of British as well as Jewish culture. When congregants are not singing in the synagogue, they may be singing in a leisure choir, joining in a folk music session or another team activity, or they may simply participate as appreciative audience members.

Both formal choirs and congregational song contribute to the translation of this aesthetic into worship, an aesthetic that resonates and finds parallels in the larger culture of which British Reform is a part. Jacobs observes that “if you’re singing with people, and you’re facing them, and they’re singing one harmony and you’re singing another, that develops community” (Jacobs 2015). Musically, British Reform worship emphasizes the value of that communal ideal and the collaborative production of beauty. Even in congregations that do not specialize in highly musical worship, I have seen congregants make at least a small effort to join their voices, if not in song, then at least in a collaborative attempt at melodic prayer. Whether the collaboration comes from a formally trained choir representing the voices of the congregation or the congregation themselves, singing in harmony to become their own choir, congregants in British Reform synagogues find both religious propriety and a sense of Britishness in calling each other to prayer.

Acknowledgements

An early version of this essay was presented at the conference “Magnified and Sanctified: The Music of Jewish Prayer” in June 2015 in Leeds. I would like to thank the following people and institutions for their generous support of my work and their assistance in shaping and refining the ideas in this article: Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge; Stephen Muir and the Performing the Jewish Archive project; Cambridge University Jewish Society, Beth Shalom Reform Synagogue, Finchley Reform Synagogue, Sinai Synagogue; Benjamin Wolf, Danielle Padley, Barbara Borts, Jeffrey Summit, Nicholas Danks, Chloe Alaghband-Zadeh, and Ruth Davis.

References

BBC. 2020. “BBC Two – The Choir.” Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b008y125. Accessed 9 March, 2020.

–––––. 2020B. “BBC One – Last Choir Standing.” Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00cktt1. Accessed 9 March, 2020.

Bender Atik, Ruth. 2015. Interview by author, 21 June. Leeds, England. Digital recording. Private collection.

Bennett, Peggy D. 1984. “Sarah Glover: A Forgotten Pioneer in Music Education.” Journal of Research in Music Education 32(1): 49–64.

Borts, Barbara. 2020. “The Changing Music of British Reform Judaism.” The Journal of Synagogue Music 45(1): 40–75).

Chernett, Jaclyn. 2010. Interview by author, 30 July. London, England. Digital recording. Private collection.

Cohen, Rabbi Francis L., and David M. Davis. 1899. The Voice of Prayer and Praise: A Handbook of Synagogue Music for Congregational Singing. Reprinted 1933. London: Office of the United Synagogue.

Edelman, Marsha Bryan. 2021. “At the Intersection of Music, Judaism and Community: Jewish Choral Singing in America.” Journal of Synagogue Music 46(1): 40–43.

Endelman, Todd M. 2002. Jews in Britain 1656 –2000. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Finlay, Joseph. 2015. “Shirim chadashim – new music for synagogue services.” Workshop presented at Limmud Conference, 30 December. Digital recording. Private collection.

Friedmann, Jonathan. 2012. Social Functions of Synagogue Song: A Durkheimian Approach. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Gait, Michael. 2015. Interview by author, 12 March. Cambridge, England. Digital recording. Private collection.

Jacobs, Cantor Zöe. 2015. Interview by author. 1 May. London, England. Digital recording. Private collection.

Kadish, Sharman. 2003. “Constructing Identity: Anglo-Jewry and Synagogue Architecture.” Architectural History 45: 386–408.

Knapp, Alexander. 1996 – 1998. “The influence of German music on United Kingdom synagogue practice.” Jewish Historical Studies 35: 167–197.

Levy, Sheila. 2015. Interview by author. 17 April. Cambridge, England. Digital recording. Private collection.

McGuire, Charles Edward. 2009. Music and Victorian Philanthropy: The Tonic Sol-Fa Movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Myer, Michael A. 1988. Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Neapolitan, Denise. 2015. Interview by author. 30 April. Cambridge, England. Digital recording. Private collection.

Padley, Danielle. 2015. Interview by author, 28 January. Cambridge, England. Digital recording. Private collection.

–––––. 2019. “Tracing Jewish Music beyond the synagogue: Charles Garland Verrinder’s Hear my cry O God.” Nineteenth-Century Music Review 17(2): 1–43.

Padley, Danielle, and Susan Wollenberg. 2020. “Charles Garland Verrinder: London’s First Synagogue Organist.” In Jewishness, Jewish Identity and Music Culture in 19th-Century Europe, ed. Luca Lévi Sala. Bologna: UT Orpheus. 167–184.

Rubinstein, William D., Michael A Jolles, and Hilary L. Rubinstein. 2011. The Palgrave Dictionary of Anglo-Jewish History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Russell, Dave. 1987. Popular Music in England, 1840–1914. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Samama, Leo. 2012. “Choral music and tradition in Europe and Israel.” In The Cambridge Companion to Choral Music, ed. André de Quadros. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 79–103.

Standard Sport. 2018. “FA Cup Final 2018: Fan choir to sing ‘Abide With Me’ before Chelsea vs Manchester United.” Evening Standard, 19 May. Available at https://www.standard.co.uk/sport/football/fa-cup-final-2018-fan-choir-to-sing-abide-with-me-before-chelsea-vs-manchester-united-a3843361.html. Accessed 29 February, 2020.

Stone, Jon. 2015. “Fan choir singing ‘Abide With Me’ to open FA Cup Final this year.” The Independent, 17 January. Available at https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/football/fa-league-cups/fan-choir-singing-abide-with-me-to-open-fa-cup-final-this-year-9985054.html. Accessed 29 February, 2020.

Temperley, Nicholas. 1979. The Music of the English Parish Church, Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wright, David. 2012. “The Music Exams of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce, 1859–1919.” In Music and Institutions in Nineteenth-Century Britain, ed. Paul Rodmell. Farnham, Ashgate. 161–180.

Ynysowen Male Voice Choir. 2018. “Ynysowen Male Voice choir.” Available at https://ynysowenmalevoicechoir.webs.com/. Accessed 29 February, 2020.

[1] Louis Lewandowski’s setting of Psalm 92, “Tzaddik Katamar,” sung by the Kol Echad choir, Cambridge. Recording courtesy of Kol Echad and Danielle Padley.

[2] I thank Michael Gait for permission to consult Beth Shalom’s records from the 1980s; private collection.

[3] Beth Shalom congregational records; private collection.