Reimagining the Poetic and Musical Translation of “Sensemayá”

To assume that every recombination of elements is necessarily inferior to its original form is to assume that draft nine is necessarily inferior to draft H—for there can only be drafts. The concept of the “definitive text” corresponds only to religion or exhaustion.

Jorge Luis Borges, “The Homeric Versions” (1932)

In this article, I aim to analyze in detail the cross-comparative relationship between the poem “Sensemayá” from the 1934 West Indies, Ltd. publication by Afro-Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén, and the 1938 orchestral piece Sensemayá by Mexican composer Silvestre Revueltas. Stemming from extensive studies on this subject as posited by Charles K. Hoag, Peter Garland, and Ricardo Zohn-Muldoon (1987; 1991; 1998), I would like to propose an alternative theoretical mode of conceptualizing and reconfiguring this musico-literary comparative analysis by drawing from a theory of translation posited by Jorge Luis Borges (Kristal 2002). More specifically, this theory of translation dissolves the linear historicity or the sacredness of the “original work” that the translator is beholden to as faithfully or unfaithfully translating the work at hand.1 Instead, Borges conceptualizes the act of translation, and the translation itself, as a process of recreation that holistically takes into account the translator’s creative license in light of the work he or she is translating. Rather than reducing this process linearly, translation studies within a Borges theoretical framework opens the possibility of examining processes of translation as a constellating continuum of several components such as the historical, aesthetic, and linguistic pieces that contextualize this process. The studies conducted by Hoag, Garland, and Zohn-Muldoon operate under this more traditional mode of linear historicity that I intend to dissolve in my case study.

Drawing from Borges and considering Revueltas’s piece as a translation of Guillén’s poem, the domains of music and poetry as manifested in these two works demonstrate overlaps that need to be carefully discussed. In order to determine the aesthetic decisions made by Guillén and Revueltas, I will compare specific rhythmic variations, stress accents, meter, and linguistic tonal devices operating within the poem of “Sensemayá.” Then I will determine how these devices are transformed in Sensemayá. To open this in-depth analysis, I will lead with a recording by Nicolás Guillén reciting “Sensemayá” and argue the methodological and historical importance of listening to the recited poem in addition to reading the poem as a critical first-step to this poetic and musical process of translation. This approach will shift the critical studies of Revueltas’s Sensemayá as it relates to Revueltas’s handwritten manuscript (Garland 1991), the bass ostinato (Hoag 1987), and other rhythmic elements in the piece. This literary and audio analysis of the poem, not conducted in such depth in the previous studies, is paramount to understanding why a composer would value Guillén’s poem as an integral point of departure for Sensemayá. I suggest that the tonal and metric variations that operate in Sensemayá more clearly inform our understanding of the inherent musical and tonal characteristics in the poem. Additionally, I will discuss the specific ideological, racial, and social issues Guillén raises when poeticizing this Afro-Cuban religious ritual, as well as how these raised issues connect to Revueltas’s and Guillen’s shared political and intellectual sympathies particular to Cuba and Mexico in the 1930s.

By conducting a micro-analysis of one instance where a poem is set to music, I propose a more detailed methodological approach to examining the cross-comparative aesthetic, musical, and poetic particularities in both works. Consequently, I would like to dissolve the discursive mechanisms that have positioned Guillén and Revueltas as isolated figures quarantined in their specific national, artistic, political, and public identities and affiliations. Reevaluating this comparative study illustrates a more complex matrix of sociological, religious, poetic, and musical values that relationally position Guillén and Revueltas as artists, intellectuals, political activists, and friends.

Borges: Theory of Translation as a Lens for Comparison

Ricardo Zohn-Muldoon provides an extensive study that “attempts to precisely ascertain how Revueltas based his symphonic work on Guillén’s poem” (Muldoon 1998:155). He concludes that this process of integrating poetic form into music form constitutes part of the “wonderful cycle of transliteration begun by Guillén’s reenactment of an Afro-Cuban snake rite in his poem, and brilliantly continued by Revueltas’s reenactment of Guillen’s poem in his symphonic work” (155). Zohn-Muldoon’s choice of “transliteration”—the rendering of the letters or characters of one alphabet system into those of another alphabet system—is the very concept that I wish to examine. By extension, I will consider “translation,” as theoretically framed by Borges, to reconceptualize the bridge between poetic and musical form. I argue that Zohn-Muldoon falls short in suggesting that Guillén’s poem begins this cycle of transliteration through reenacting the Afro-Cuban snake rite, which is continued in Revueltas’s reenactment of Guillén’s poem. What Zohn-Muldoon does not recognize is that the process of transliteration of Guillén’s poem to Revueltas’s piece does not begin and end there—they are both part of a greater continuum. To suggest that Revueltas bases his symphonic work on Guillén’s poem is to ignore the notion that Revueltas had the creative license to transform and recreate the poem in musical form.

Efraín Kristal positions Jorge Luis Borges’s short stories as doctrines of translation that provide an alternative theoretical basis for how to critically challenge and eradicate linear historicity within the process of translation (2002).2 Zohn-Muldoon’s study upholds this linearity between Guillén’s and Revueltas’s works that I would like to reconfigure. Although Borges is concerned with literature, I would like to expand this theoretical framework to critique the translation between two different media, poetry and music. One of the recurring themes in Borges’s writings centers on the process of translation as subjected to the judgment of linear historicity (Kristal 2002). Nevertheless, Borges argues that all literature exists in a greater continuum of translations of translations: “His bias is in favor of bracketing those considerations in the hope that translations may attain the same status as original works of literature” (Kristal 2002:33). Removing the historicity or the sacredness of the original work, where the translator is beholden and evaluated against the spirit of the author, a specific ideal, or essence of the original work, Borges opens the possibility of conceptualizing the act of translation—and the translation itself—as a process of recreation rather than a literal translation or copy of the original (32). A literal translation attempts to maintain all the details of the original, but changes the emphasis, or understood meanings, connotations, associations, and effects of the work. Contrastingly, a recreation omits the many details in order to conserve the emphasis of the work, with added interpolations (32). Kristal notes that Borges believes a faithful translation is one that can retain the meanings and effects of the work, whereas an unfaithful translation changes them.

Translation as a theoretical concept allows for the negotiation and dissolution of differences and boundaries between two linguistic forms of expression and, in this particular case, two artistic media. Translation paradoxically renders the possibility and impossibility of fusing these different worlds. It is possible because these different linguistic, idiomatic, or musical modes of expression subtend a kind of sameness in the forces that drive them; it is impossible because of the nuanced residues of expressive modes that cannot be fully conveyed across linguistic and musical divides. Guillén and Revueltas shared in the same spirit of political activism of La Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (LEAR) (League of Writers and Revolutionary Artists)—resisting fascism and sharing a deep friendship. They also shared in the effort not only to respect each other’s artistic endeavors, but to translate them into their own work.

Guillén and Revueltas: Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios

Nicolás Guillén and Silvestre Revueltas were brought into acquaintance with one another in 1937 when Guillén received an invitation to participate in El Congreso de Escritores y Artistas convened by LEAR, (Augier 1965:200). LEAR was an organization of artists and intellectuals whose political and social ideals aligned with the Mexican Communist Party during the 1934-1940 administration of Lázaro Cárdenas government (Azuela 1993). Before meeting Revueltas, Guillén had already published three collections of poetry—Motivos de Son (1930), Sóngoro Cosongo (1931), and West Indies Ltd. (1934)—all in a time period that marked a dramatic political turn in Cuba after the fall of the dictator Gerardo Machado and the takeover of the Communist Party. In addition to low labor wages, mass poverty, and the struggle against the Machado dictatorship and their imperialist sympathies, Guillén also concerned himself with racial and social injustices. He contributed significantly to the literary movement of black poetry in his poetic works, newspapers, and magazines (Augier 1965:158-159). Guillén shared the same political sentiments with LEAR and, by extension, the Spanish Republic battling against Franco’s fascist party.

LEAR defined itself as a proletarian organization seeking to restore diplomatic relations between Mexico and Soviet Russia, promote true culture for the productive masses, legalize the Communist Party, and raise class-consciousness of the revolutionary proletariat (Azuela 1993:85-86). From 1934-1938, LEAR built an alliance of poets, painters, musicians, playwrights, educators, scientists, architects, and filmmakers who published in LEAR’s journal Frente a Frente (Head to Head), fulfilling their social function as revolutionary intellectuals and pointing out the dangers of cultural production at this time (Hess 1997). In addition to Revueltas and Guillén, LEAR members included poet Juan Marinello, Mexican poets Carlos Pellicer and Octavio Paz, the Republic’s ambassador to Mexico Félix Gordón Ordás, the Mexican composer Luis Sandi, the painter Fernando Gamboa, Gamboa’s wife and journalist Susana Steele de Gamboa, the poet and writer María Luisa Vera, the author of children’s literature Blanca Trejo, and Revueltas’s brother José Revueltas (Hess 1997:297). The editorial policies, declarations, and illustrations of each publication expressed the artists’ commitment to contemporary social issues, employing culture as a weapon against fascism, Nazism, and imperialism.

Revueltas served as LEAR president from May 1936 until February 1937 (Revueltas 2002). In 1936 the Spanish Civil War broke out and ignited LEAR’s active support. In response, Revueltas and LEAR organized the 1937 Congreso de Guadalajara (Congress of Guadalajara) in Mexico, whose attendees included Nicolás Guillén, José Chávez Morado, Octavio Paz, María Luisa Vera, Elena Garro, and José Mancisidor. Collectively, they formed part of a delegation that traveled to Spain and attended the Congress of Valencia to demonstrate solidarity with the Spanish Republic (Revueltas 2002).

Consequenctly, Revueltas and Guillén solidified their friendship as political compatriots, fellow intellectuals, and artists during the Congress of Guadalajara and their subsequent visit to Spain. During the social gatherings in the course of their stay in Guadalajara, many of the writers and artists shared their work with one another. According to Eugenia Revueltas, daughter of Silvestre Revueltas, the members would gather at La Casa Kostakowski—a social space where Revueltas would gain the inspiration to compose Sensemayá after listening to Guillén recite “Sensemayá” (2002:180).

In addition to Guillén, Revueltas established friendships with other poets that shared his political and aesthetic values, including Mexican modernist poet Ramón López Velarde, Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, and Mexican poet Carlos Pellicer. According to an account given by Pellicer, the poet and composer solidified their friendship during their 1937 visit to Spain (1973:25). On their ship ride from Spain to Mexico, Revueltas personally requested a copy of Pellicer’s collection of poems, Hora de Junio (1937). Shortly thereafter, Revueltas telephoned Pellicer informing him that he had composed a small orchestral piece for woodwinds, piano, and percussion entitled Tres Sonetos—a piece inspired by three sonnets from Pellicer’s Hora de Junio (Pellicer 1973:25). This is yet another musico-literary moment with Revueltas worth studying in more depth.

Folklore and Ideology in Guillén’s “Sensemayá”

The word sensemayá is a combination of sensa (Providence) and Yemaya (Afro-Cuban Goddess of the Seas and Queen Mother of Earth). The poem poeticizes an Afro-Caribbean snake dance rite conducted by the practitioners of the Palo Monte Mayombe religion. Palo Monte Mayombe derives originally from the Central African Bakongo and other Bantu cultures (primarily in the Congo, Cameroon, and Angola), and it is one of the leading Afro-Caribbean creole religions of the largest Spanish-speaking Antilles (Murrell 2010). The religion operates in concordance with nature, and it places strong emphasis on the individual’s relationship to ancestral and nature spirits and its practitioners. The Palo mayombero specialize in infusing natural objects with spiritual entities to aid or empower humans to negotiate the problems and challenges of life (Murrell 2010:136). Palo Monte is often referred to as Reglas Congas (Kongo religions) and has accrued more symbolic names than one wishes to count; however, these locutions share a common historical creole African-Spanish signification of an African spirituality.3 Palo and monte are creole-Cuban creations that have a distinct connection to the religious import of trees for the Bakongo people. Palo is a Portuguese and Spanish word for tree, while Mayombe is forest area in the Central African Kongo region. The Mayombe forest serves as a sacred space where courts, debates, marriages, and initiations are held; thus, Palo practitioners augur the religion’s dual Kongo and Cuban spiritual reality (136).

In the poem, the snake is portrayed not only as the snake on earth to be killed, but as the sacred Infinite represented by the Snake itself—a spiritual entity with which the mayombero or Palo infuses the snake. The killing of the snake, a sacred creature, symbolizes renewal, fertility, growth, and wisdom. This is because snakes shed their skin annually, linking them to the rainbow, heavens, gods, and the earth for African and pre-Christian civilizations (Kubayanda 1990:105). Because it is a dance ritual, the bàtá drums are usually deployed, with the iyá (mama drum) playing the dominant role (105).

Another interpretation by Keith Ellis discusses the poem’s heightened feelings and emotions, as manifested primarily by the rhythmic refrains, finding them to be excessively serious for folklore about killing a snake. The snake acquires a status of symbolizing imperialism and the need for definitive liberation (1983:83-84). Additionally, the title of the collection of poems, West Indies Ltd., suggests the geographical unity of the territories that form the imperialist enterprise conveyed by Ltd. (85). Ltd. alludes to several islands of the West Indies, including Cuba, Haiti, and Jamaica, which had sugar estate work forces of primarily black African descent and managed by North American commercial industries.

Kubayanda finds that Ellis’s conclusions reduce the poem’s significance to merely social and political ends (1990; 1983); in so doing, Ellis ignores the ritual and Afro-Cuban creole specificities of this snake dance. According to Kubayanda’s interpretation, the snake-spirits are common among Bantu cultures in Zaire and East Africa. The death of the snake represents not a silence of extinction, but a silence that stands in harmony with Creation and the Absolute (Kubayanda 1990:107). Taking both Ellis and Kubayanda’s interpretations into account, this poem brings sociological, historical, and ethnographic value to the greater social consciousness of Cuba that Guillén raises.

Upon the publication of West Indies Ltd., Guillén conducted readings and lectures of his poems at the conference “Cuba: Pueblo y Poesía” (“Cuba: Popular and Poetry”) at the Institución Hispanocubana de Cultura in 1937 (Augier 1965:198). His lectures discussed the historical importance of creating an African-Spanish reawakening of national consciousness in Cuba, a reawakening that would include the African languages, music, religions, and rituals that contributed to the historic and economic development of Cuba as a nation (Ellis 1983:83-84). Guillen’s commitment to the social injustices the African black criollo community faced would weave itself through “Sensemayá,” through the integration of Spanish verse with Central African Bakongo vernacular and rituals.

Sensemayá Canto para matar una culebra | Sensemayá Chant to kill a snake |

|---|---|

¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé!

La culebra tiene los ojos de vidrio; la culebra viene y se enreda en un palo; con sus ojos de vidrio, en un palo, con sus ojos de vidrio.

La culebra camina sin patas; la culebra se esconde en la yerba; caminando se esconde en la yerba, caminando sin patas.

¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé!

Tú le das con el hacha, y se muere: ¡dale ya! ¡No le des con el pie, que te muerde, no le des con el pie, que se va!

Sensemayá, la culebra, sensemayá. Sensemayá, con sus ojos, sensemayá. Sensemayá con su lengua, sensemayá. Sensemayá con su boca, sensemayá . . .

La culebra muerta no puede comer; la culebra muerta no puede silbar; no puede caminar, no puede correr. La culebra muerta no puede mirar; la culebra muerta no puede beber; no puede respirar, ¡no puede morder!

¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, la culebra . . . ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, no se mueve . . . ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, la culebra . . . ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Sensemayá, se murió! | Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé!

The serpent has eyes made of glass; The serpent comes, wraps itself round a stick; with its eyes made of glass, round a stick, with its eyes of glass.

The serpent walks without any legs; The serpent hides in the grass; walking hides in the grass, walking without any legs.

¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé!

Hit it with the ax, and it dies: hit it now! Don’t hit it with your foot, it will bite you, Don’t hit it with your foot, it will flee!

Sensemayá, the serpent, sensemayá. Sensemayá, with his eyes, sensemayá. Sensemayá, with his tongue, sensemayá. Sensemayá, with his mouth, sensemayá . . .

The dead serpent cannot eat; the dead serpent cannot hiss; cannot walk, cannot run. The dead serpent cannot see; the dead serpent cannot drink; cannot breathe, cannot bite!

¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, the serpent . . . ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, is not moving . . . ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, the serpent . . . ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, he is dead! |

Figure 1. Guillen’s “Sensemayá.” English translation by Roberto Márquez (The Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry: A Bilingual Anthology 2009:221-222).

Musico-Literary Analysis of “Sensemayá” and Sensemayá

Borges’s theory of translation provides a fruitful approach for placing Revueltas’s Sensemayá and Guillén’s “Sensemayá” in comparative dialogue with one another. Revueltas’s work represents a process of transforming and recreating Guillén’s poem while remaining faithful in conserving the emphasis of Guillén’s work; however, the current scholarship on this subject, as initiated by musicologist Peter Garland and further developed by Zohn-Muldoon (1991; 1998), construe this process to be more of what Borges discourages—that of interpreting Sensemayá as a literal translation of “Sensemayá.” Both musicologists argue that Revueltas maintains all the details of the original while taking some liberty to transform the poem into an orchestral piece.

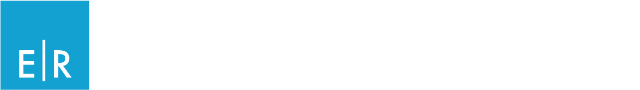

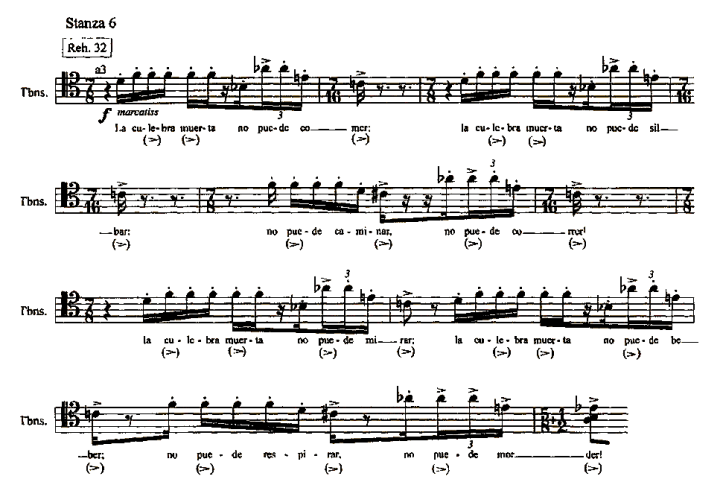

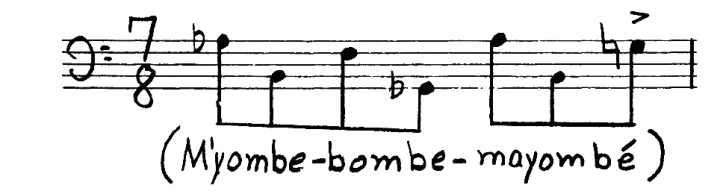

The basis of this argument stems from Peter Garland’s 1991 research, which draws on the fact that two versions of Sensemayá were originally written: the first score, composed in May 1937, is scored for chamber orchestra and is more sparse and open-textured; the second score, completed in March 1938, is for a much larger ensemble (Garland 1991:181). Referencing the original handwritten manuscript of the first version, Garland points out the two places in the score where Revueltas himself penciled in the text of the poem underneath the musical themes that correspond to them. The first example (Figure 2) shows the handwritten notation reflecting the syllabic characteristics of the poem’s refrain, “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé!” In the second example (Figure 3) Garland shows a similar case with the poem’s line “La culebra tiene los ojos de vidrio” (“The snake has eyes of glass”) handwritten below the equivalent musical notation.

Figure 2. Sensemayá, “Mayombe” theme from version one (manuscript) starting at rehearsal no. 6, measure 5; and from published score, rehearsal no. 11, measure 2, strings (Garland 1991:182)

Figure 3. Sensemayá, theme/section corresponding to stanza from version one, starting at rehearsal no. 7, measure 5 in the trumpets; and from the published score, starting at rehearsal no. 13, measure 2 (brass) (Garland 1991:184)

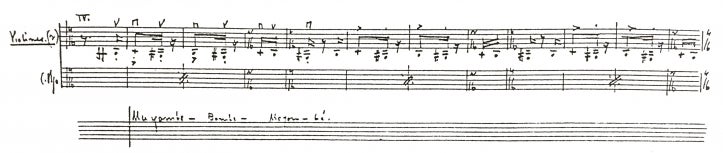

In both examples, Garland compares the unpublished version scored for chamber orchestra with the published final version scored for a larger orchestra. From these findings, Garland concludes that “the whole structure of Sensemayá falls into place quickly, and with surprising similarities and structural affinities with the poem. The text-music relationship is indeed more literal than simply an ‘evocation’” (1991:132). Garland interprets the literal text-music relationship as the equivalence of syllables and rhythmic notation. He discusses a third instance where the title word “Sensemayá” can be rhythmically identified in the tom-tom and bass drum, which, played in the first measures, provides one of the keys to the entire rhythmic identity of the piece.

Figure 4. Sensemayá, opening measures: “sensemayá” theme articulated in tom-tom part (Garland 1991:184)

Similar to the other two cases, Garland highlights a syllabic relationship with rhythmic notation to show how Revueltas may have applied this concept in Sensemayá. As played by the tom-tom and bass drum, each syllable of “sensemayá” is represented by single eighth notes.

Although Garland makes a convincing case about these two specific instances where Revueltas’s may have conducted a more literal translation from text to musical notation, Garland is too quick to argue that the rest of the orchestral piece follows this mimesis. Garland does not provide evidence of any additional handwritten notes, which leads me to surmise that Revueltas perhaps was not as concerned with this literal text-music relationship as Garland suggests. Revueltas may have taken these specific poetic motifs as points of departure for recreating the poem according to his creative preferences and skill. His translation is one that does not concern itself with maintaining all the details of the original, but rather exercises his compositional techniques to produce a recreation of the poem.

Similarly, Zohn-Muldoon also takes Garland’s literal text-music relationship, but he expands the interpretation of the orchestral piece to suggest that it also projects the stanzaic structure, dramatic and symbolic meaning, and atmosphere of the text. He suggests that Sensemayá was designed as a song:

In fact, it seems to me almost inconceivable that a composer of Revueltas’ stature would have gone through so much trouble in faithfully setting every word of the text had his compositional intent been solely to obtain and justify a melodic contour and sectional divisions. It is a far more congruous proposition to assume that both the compositional process and the musical material in Sensemayá are designed, as in a song, to forcefully project and expand the meaning of the text. (1998:143–144)

To an extent, Zohn-Muldoon embraces the notion that Revueltas takes the musical and artistic license to recreate and expand the meaning of the poem. He goes through a series of interpretations discussing how Revueltas renders the performance of the snake rite musically: the opposing forces of man (embodying good) and the snake (embodying evil) represented by the woodwinds and low brass instruments; the agonizing climax of killing the snake as manifested through the inclusion of loud noise (gongs and cymbals); the pitch continuum (the glissando in the strings); and its general harmonic stasis and repetitive melodic fragments (Zohn Muldoon 1998:146). In short, Zohn-Muldoon believes the orchestral piece tells the story of the snake rite, where the music instruments “sing” the text of the poem underlined with “cinematic procedures in order to comment or depict events narrated in adjacent stanzaic passages or events implied between the stanzas that precede it and follow it” (1998:144). But his interpretation of how Revueltas expands the meaning of the poem fundamentally relies on this literal text-music translation. Zohn-Muldoon attempts to finish the work that Garland initiated, assigning every word to notation in order to support his argument that the poem can be construed as a song form.

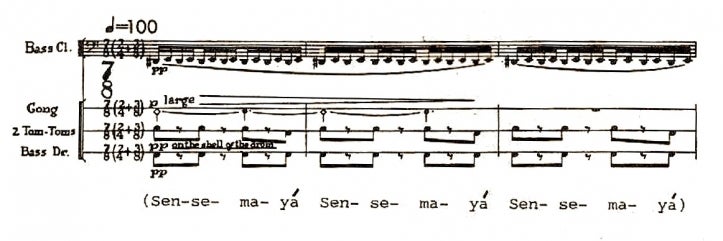

Figure 5. Stanza 6, rehearsal no. 32 (Zohn-Muldoon 1998:142)

Zohn-Muldoon assigns the text to sixteenth notes with the implication that the trombones “sing” the verses; however it remains questionable whether Revueltas would have composed such a simulacrum of text to music. Because the tempo of the piece is marked at one hundred beats per minute, these words would be recited and sung at an inconceivably fast rate. The final syllable of the words “sil-bar,” “co-mer,” “mi-rar,” be-ber,” and “mor-der” are delayed and implanted in the next measure, creating awkward and choppy phrasing. It construes a musical inconceivability and unsoundness of assigning the text to these notations, and singing this text aloud could sound awkward and choppy.4

Zohn-Muldoon attempts to be highly exact in matching syllables to notes. When considering the musical conceivability of this, it leads to the conclusion that Revueltas was inevitably subsumed and swallowed by the text’s functions. Zohn-Muldoon’s analysis upholds the historicity and sacredness of the original that he construes Revueltas to also remain beholden to.

Garland and Zohn-Muldoon’s analyses suggest an exact text-music relationship that could recall Borges’s short story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” (1944). Borges shares Novalis’s idea that a translator is allowed to transform the original, but he remains indifferent to Novalis’s view that the translator should act in the writer’s spirit (Kristal 2002). For Borges, the translator should not be held to the demand that they should merge with the original writer’s spirit. Borges’s indifference to Novalis’s view is illustrated in the short story when Menard considers becoming one with Cervantes; however, he soon rejects the idea and continues with his project of producing a work that becomes identical to pages found in Don Quixote. Ultimately, Menard continues as himself and not as Cervantes (Kristal 2002:31). The literal text-music analysis that Garland and Zohn-Muldoon conduct implicitly positions Revueltas as beholden to the spirit and essence of the author Guillén. With this interpretation, Revueltas appears to have little or no creative license to change and transform the poem in new ways.

But the question still remains: Why would Revueltas choose to conduct this literal syllabic-musical note translation with the moments “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé” and “La culebra tiene ojos de vidrio,” as evident in the original manuscript? Garland and Zohn-Muldoon’s literal text-musical note analysis provides little speculation as to why this is so, primarily because their scholarship misses the careful attention and analysis that the poem itself merits. Both musicologists take the text and content literally without recognizing the fundamental ideophonic, musical, and rhythmic forms of the poem that are crucial in the understanding of it and the Afro-Cuban snake rite that it poeticizes. To argue that Revueltas saw the poem as mere “text,” as Garland and Zohn-Muldoon posit (1991; 1998), is to ignore the poetic devices that enliven a musical experience in the poem; these provide a new layer of understanding to the translation process. This recreation also needs to take into account the aesthetics of the poem itself—aesthetics that Revueltas translates and recreates in his orchestral piece. I attempt to deepen the analysis of the poem and focus more closely on the poem’s musicality and the poetic devices with which it is imbued. My hypothesis reconfigures the two moments illustrated in the original manuscript to determine how and why Revueltas translates this in his orchestral piece.

Listening to “Sensemayá”

Returning to Eugenia Revueltas’s article, let us revisit the moment in 1937 when Guillén recited “Sensemayá” aloud in La Casa Kostakowski. As Eugenia Revueltas states, Revueltas “no perdía una palabra y estaba atento a su lectura” (“Revueltas did not miss a word and was attentive to his reading”) (2002:180). What is key is that Revueltas heard this poem recited, suggesting that Revueltas may have also identified the rhythmic, metric, and accentual characteristics of the poem. In the recording of Guillén reciting “Sensemayá,” there are more clues as to what this experience may have been like for Revueltas.

In the 1960s Nicolás Guillén recorded a vinyl record, El son entero en la voz de Nicolás Guillén, where he recited “Sensemayá” and twenty-two other poems from his various published works.5 Published in Buenos Aires by Collección Poetas, this album is part of a series that also recorded the Spanish poets Federíco García Lorca’s and Juan Ramón Jiménez’s poetry. Spanish poet Rafael Alberti Morello, a personal friend and political compatriot of Guillén, served as the author of the album’s back cover.6 He describes Guillén’s published works, highlighting Guillén’s commitment to voice the social and political struggles in Cuba and of the greater Caribbean through poetry and song. Additionally, Alberti sheds light on the musicality of Guillén’s voice:

Canta Nicolás Guillén con milagrosa facilidad. En todas las épocas de su poesía la universalidad de su voz alcanza a representar todolos hombres, pues puede oírse de diferentes maneras: atendiéndose a su profundidad o su gracia, bailando o doliéndose. Cuando es la propia voz del poeta la que dice sus hermosos versos pocas veces alcanzara la poesía tan alto nivel de belleza. (Alberti, El son entero en la voz de Nicolás Guillén)

Nicolás Guillén sings with miraculous ease. Throughout the eras of his poetry, the universality of his voice has come to represent all men that can be heard in different forms: speaking to its profundity or its grace, dancing, or in pain. When it is the poet’s own voice who recites his beautiful verses, poetry shares in the rare moment of reaching a higher level of beauty.7

Guillén recites the entire poem in a consistent and precise tonal, rhythmic, and metric form. This can be most explicitly heard in the “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé!” and “Sensemayá” poetic motifs. Guillén consistently and precisely recites the accented stresses of these lines, which are underlined by the 8-meter count.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Meter: 8 | |

| May | OM | be— | BOM | be— | / | May | om | BÉ | Accent Stress: 2, 4 / 3 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Meter: 8 | |

| Sen | se | ma | YA! | / | la | cul | EB | ra, | Accent Stress: 4 / 3 |

| Sen | se | ma | YA! | Accent Stress: 4 | |||||

| Sen | se | ma | YA! | / | con | sus | OJ | os, | Accent Stress: 4 / 3 |

| Sen | se | ma | YA! | Accent Stress: 4 | |||||

| Sen | se | ma | YA! | / | con | sus | LEN | gua, | Accent Stress: 4 / 3 |

| Sen | se | ma | YA! | Accent Stress: 4 | |||||

| Sen | se | ma | YA! | / | con | su | BO | ca, | Accent Stress: 4 / 3 |

| Sen | se | ma | YA! | Accent Stress: 4 |

Figure 6. Accent stress: Guillén’s “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé!” and “Sensemayá”

As Guillén recites the “Mayombe— . . .” motif, he also maintains a consistent variation in tone that rises in pitch in correspondence with the stressed accents on the word. Moreover, for “Sensemayá . . .” Guillén’s pitch rises and falls in alternating lines: in the line, “Sensemayá la culebra,” he rises in pitch with the “yá” syllable and falls with “la culebra.” In the following line, “Sensemayá,” he maintains a single pitch for the “sen-se-” and then falls in pitch for the “yá.” This is repeated for the remaining six lines of this stanza. The poem maintains this rhythmic and pitch pattern that Revueltas could have recognized and may have led him to handwrite these particular motifs in the manuscript.8 Listening to the poem recited by Guillén allows for the analysis of the musical, rhythmic, ideophonic, and tonal facets that are necessary for a critical evaluation of why this particular poem is set to music. Listening to Guillén’s recording is a critical first step towards understanding the musical and rhythmic intricacies of this poem.

The son rhythm specifically is one of the driving aesthetic principles in Guillén’s poetry. In a 1930 interview, Guillén correlates rhythm to the formation and understanding of the black Afro-Cuban:

El negro cubano—para constreñir más nuestro pensamiento—vive al margen de su propia belleza. Siempre que tenga quien lo oiga, abomina del son, que hoy tanto tiene de negro; denigra la rumba, en cuyo ritmo cálido bosteza el mediodía africano. . . . El ritmo africano nos envuelve con su aliento cálido, ancho, que ondula igual que una boa. Es nuestra música y esa es nuestra alma. (Augier 1965:94-97)

The black Cuban—to compel our thinking more—lives at the margins of his own beauty. Always when someone has to listen to him, he detests the son, which today carries so much blackness; he denigrates the rumba, in whose warm rhythm the African yawns at noon. . . . The African rhythm wraps us up in its warm, extensive breath that undulates like a boa. It is our music and it is our soul.

For Guillén, rhythmic communication represents the embodiment of a persecuted but resilient civilization, which defines Cuba socially, politically, and historically. In addition to this aesthetic principle, Guillén also incorporates the five-beat clave rhythm into several of his poems through five-syllabic lines. Poems such as “Son número 6,” “La guitarra,” and “Tú no sabe inglé” (Figure 7) incorporate this five-beat accentuated son pattern in particular stanzas of each poem.

“Son número 6” Adivinanza de la esperanza: lo mío es tuyo lo tuyo es mío; toda la sangre formando un río.

“Guitarra” El son del querer maduro, tu son entero; el del abierto futuro, tu son entero; el del pie por sobre el muro, tu son entero . . .

“Tú no sabe inglé” Vito Manué, tú ni sabe inglé, tú no sabe inglé, tú no sabe inglé. No te enamore má nunca, Vito Manué, si nos abe inglé, si no sabe inglé. | “Son number 6” Riddle of hope: what’s mine is yours what’s yours is mine; all blood forming a river.

“Guitar” The son of mature desire, your complete son; that of the open future, your complete son; that of one foot over the wall, your complete son . . .

“You don’t know English” Vito Manué, you don’t even know English, you don’t know English, you don’t know English. Don’t ever fall in love again. Vito Manué, if you don’t know English if you don’t know English. |

Figure 7. All three poem excerpts are found in an anthology of Guillén’s works: El son entero: suma poética 1929–1946 (1947/1982). “Guitarra” and “Son numero 6” are found in El son entero (inédito) (127-128, 134). “Tú no sabe inglé” is found in Motivos de Son (1930:23). English translations from Spanish are my own.

In “Son número 6” the entire stanza strongly accentuates this five-syllable rhythm, while in “Guitarra” the repeating alternating line “tu son entero” accents this five-syllable rhythm. In the third poem, the repeating line “tú no sabe inglé” carries this recurring rhythmic motif.

Guillén’s commitment to the social injustices faced by the Afro-Cuban community contributes significantly to the aesthetic decisions he undertakes to revive and reimagine the subjectivity of the black community; the most prominent means to channel this subjectivity is through “African rhythm.” Kubayanda pulls from Guillén’s own proclamations and interprets the “Sensemayá” rhythmic structure as the artistic cross-fertilization of language, polymeter, polyrhythm, and cross-rhythmic patterns. The African-Caribbean drum serves as myth, metaphor, and the aesthetic principle of Guillen’s Spanish-Yorùbá poem (Kubayanda 1993:90-91).

It is important to note, however, that Kubayanda and Guillén himself fall into the trap of essentializing the concept of African rhythm and suggesting a positive myth of what “blackness” and “African” constitutes. Since the 1990s, ethnomusicological scholarship has shifted to critically challenge the theories and conjectures made about African rhythm—a form of study that has not produced a common analytical practice or metalanguage so far (Agawu 2003). Kubayanda’s conjectures draw primarily from ethnomusicologist Arthur Morris Jones’s theories and terminologies to describe rhythm and related phenomena, which have often overcomplicated African rhythm in unproductive ways (Agawi 2003). According to Agawu, the lack of productive engagement in producing a core of organizing principles regarding African rhythm and music has “in turn facilitated the propagation of certain myths, including notions such as polymeter, additive rhythm, and cross rhythm, among others” (2003:72).8 As a result, these concepts have proven unsupportable as models in the repertoires they have been applied to, while perpetuating myths that have persisted in popular imagination and scholarly writing (72). It is more fruitful to analyze the exact rhythmic and metric devices Guillén employs in his poem that resist blanketing over-statements of “African rhythm” or “drum poetry,” and at the same time to reconfigure our understanding of Revueltas’s musical translation of an already inherently musical and rhythmic poem.

The poem’s aesthetic principles play with the classic Spanish meter and rhyme schemes in such a way that it would be false to categorize it as a poem of verso libre, or free verse (verses with different numbers of metric syllables and irregular rhyme) as Kubayanda proposes (1993). Guillén’s poem instead simultaneously conserves and resists the classic meter and rhyme schemes in Spanish poetry in an attempt to create a new poetic principle—that of stressed accents in a consistent pattern throughout each stanza. The poem calls for an examination of the rhythmic and accentual devices that constitute the main organizing principles of the poem. The poem carries out four-, six-, eight-, ten-, twelve-, and even seven-syllabic meters that are organized irregularly in the poem; the rhyme scheme upholds rima abrazada (enclosed rhyme [ABBA]), and rima cruzada (alternating rhyme [ABAB]) that are organized within each stanza. Nevertheless, the alternating forms of rhyme and meter manage to maintain the consistent accentual rhythmic form that unify the poem. Figure 8 demonstrates the breakdown of the consistent accentual and rhythmic characteristics in Spanish, Yorùbá, and the ideophonic language—despite the varying forms of meter and rhyme.

| Rhyme | Stanza | Accent Stress | Meter |

- - -

A B B A

C D D C

- - -

E F E F

- - - - - - - -

G H H G H G H G

- - - - - - - - | ¡Mayombe—bombe— / mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe— / mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—/ mayombé!

La culebra tiene / los ojos de vidrio; la culebra viene_y / se_enreda en un palo; con sus ojos de vidrio, en / un palo, con sus ojos de vidrio.

La culebra / camina sin patas; la culebra / se esconde en la yerba; caminando / se esconde en la yerba, caminando / sin patas.

¡Mayombe—bombe— / mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—/ mayombé! ¡Mayombe—bombe—/ mayombé!

Tú le das con el hacha, / y se muere: ¡dale ya! ¡No le des con el pie, / que te muerde, no le des con el pie, / que se va!

Sensemayá, / la culebra, sensemayá. Sensemayá, / con sus ojos, sensemayá. Sensemayá / con su lengua, sensemayá. Sensemayá / con su boca, sensemayá . . .

La culebra muerta / no puede comer; la culebra muerta / no puede silbar; no puede caminar / no puede correr. La culebra muerta / no puede mirar; la culebra muerta / no puede beber; no puede respirar, ¡no puede morder!

¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, la culebra . . . ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, no se mueve . . . ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! Sensemayá, la culebra . . . ¡Mayombe—bombe—mayombé! ¡Sensemayá, se murió! | 2, 4 /3 2, 4 /3 2, 4 /3

3, 5 / 2, 5 3, 5 / 2, 5 3, 6 / 2 3, 6

3 / 2, 5 3 / 2, 5 3 / 2, 5 3 / 2

2, 4 / 3 2, 4 / 3 2, 4 / 3

3, 6 /3 3 3, 6 /3 3, 6 /3

4 /3 4 4 / 3 4 4 / 3 4 4 /3 4

3, 5 / 2, 6 3, 5 / 2, 6 2, 6 2, 6 3, 5 / 2, 6 3, 5 / 2, 6 2, 6 2, 6

2, 4 / 3 4 /3 2, 4 / 3 4 /3 2, 4 / 3 4 /3 2, 4 / 3 4 /3 | 8 8 8

12 12 10 7

10 10 10 7

8 8 8

10 3 10 10 (9+1 agudo)

8 4 8 4 8 4 8 4

12 (11+1 agudo) 12 (11+1 agudo) 6 6 ( 5+1 agudo) 12 (11+1 agudo) 12 (11+1 agudo) 6 6 (5+1 agudo)

8 8 8 8 8 8 8 8 (7+1 agudo) |

Figure 8. Breakdown of consistent accentual and rhythmic characteristics

The two main and repeating rhythmic motifs in the poem that Revueltas actively translates in Sensemayá are the repeating Yorùbá “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé” stanzas and the ideophonic “Sensemayá” stanzas. Their constructed accentual stresses on 2, 4 / 3 and 4 / 3 create a consistent rhythmic pattern that Revueltas could have recognized when listening to Guillén’s recitation. The final stanza of the poem represents the unification of these two repeating motifs. It simultaneously creates a perfect metric and rhythmic unity—the stanza’s meter remains in eight, while the rhythm has an alternating pattern of 2, 4 / 3 and 4 / 3. The final stanza represents the ultimate unity and harmony at various levels: the unity of languages (Spanish, Yorùbá, and ideophony); the unity of rhythmic and accentual form; the unity of meter; and as Kubayanda suggests, the ideological unity of Creation and the Absolute as manifested through the snake itself (1993). When placing the poem in the Afro-Cuban consciousness that Guillén adamantly commits to in the 1930s, the poem would render a constellation of the histories, poetic traditions, and languages. The poem’s hemistiches are positioned according to the natural pauses and tempo of reciting the poem out loud, an essential device that serves as the basis for the placement of accentual stresses in each verse. Traditionally, hemistiches are utilized in verses of nine or more syllables per verse to create a natural pause for breath and to divide the verse in two parts of equal syllabic counts. Guillén’s verses also call for a hemistich in each verse, although they do not create the equal set of syllabic counts as in a classic Spanish poem. When looking at the poem in its entirety, “Sensemayá” appears to have an irregular placement of hemistiches; however, when considering each stanza individually, the placement of the hemistiches serves a logical function in the recitation of each stanza. For example, in stanza three the hemistich falls after “La culebra” and “caminando.” It preserves the consistent four-syllabic unit in the decameter verse that is countered in the following six-syllable unit. But as mentioned before, the hemistiches are positioned so as to keep the unifying rhythmic patterns of each stanza.

Moreover, the ideophone employed in the word “sensemayá” is a vivid representation of the stress placed on the accentual and syllabic characteristic of the poem. The ideophone is an idea in sound specified as an onomatopoeic word. It is used not only to express or describe a sound, but also a motion or action, a condition or state, or even an abstract idea (Kubayanda 1993). Phonological ideophones are usually monosyllabic or disyllabic words with duplicated identical sounds; due to their rising and falling glides or tones, and their rhythmic repeats, they can be effective for musical reproduction and poetic communication (Kubayanda 1993). The sound symbol of “sensemayá” echoed before and after the death of the snake poetically represents this phenomenon of sound and rhythm, creating the hissing ideophonic sound of the snake.

The predominant rhythmic characteristic in “Sensemayá” as demonstrated above leads to a clearer understanding of why Revueltas would be inspired to include the two motifs “sensemayá” and “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé” as integral and driving components in his piece. As I will demonstrate in the next section, Revueltas’s specific decisions related to meter and rhythm, such as setting the piece in 7/8 time with other overlapping time signatures, will have more parallel resonance with the rhythmic structure of the poem—a telling point of recreation and transformation from poetry to music than has not been previously examined.

Variations of Rhythm in Sensemayá

In the comparative study of aesthetic values between Stravinsky and Revueltas, Charles K. Hoag (1987) examines the form of ostinato and static repetition as the viable compositional devices that both Stravinsky and Revueltas, a knowledgeable follower of Stravinsky’s work, employ. In Stravinsky’s attempt to break from the European art music of linear progression and logical development as was characteristically known in Germanic and other western genres of music (Bartlett 2003), he became increasingly interested in other viable alternatives of non-European music—including jazz—that ultimately leads to his experiments in meter, rhythm, tonality, stress, and dissonance most poignantly observed The Rite of Spring (Gloag 2003). This trend carried forward in Revueltas’s interest in non-European forms, as seen in Sensemayá (Hoag 1987).

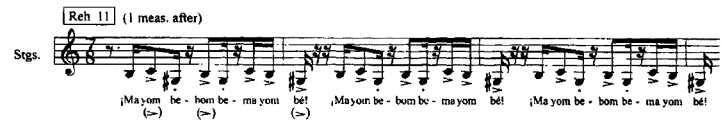

As Hoag examines, one of the two main motifs, “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé,” is primarily carried out by the all-pervading 7/8 bass ostinato, complete with the final accent on the seventh beat and reinforced by claves.

Figure 9. Sensemayá, main motif (Hoag 1987:174)

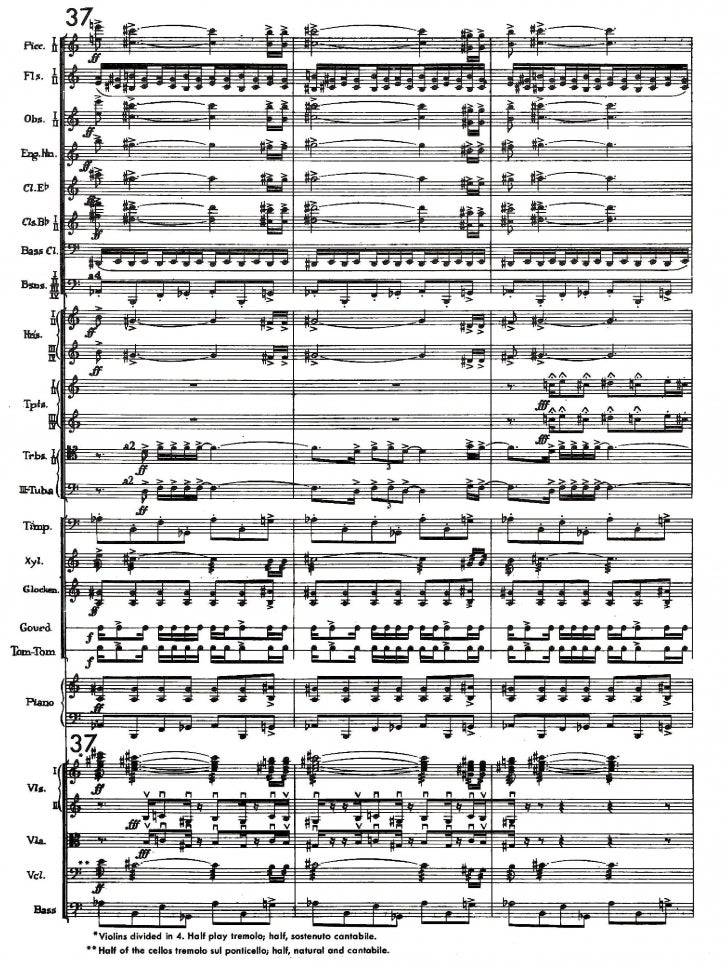

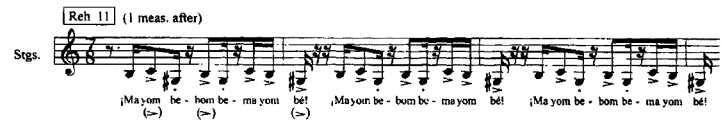

Hoag continues that the second rhythmic pattern based on the same phrase of “Mayombe . . . ” is heard over the bass ostinato one measure after rehearsal number 11 in the upper strings, and heard once again after number 12, this time two beats earlier in the measure (174).

Figure 10. Sensemayá, rehearsal no. 11 (Hoag 1987:174)

Hoag concludes that these two juxtaposing rhythmic patterns are heard throughout the work. He continues to examine the other comparative moments in Sensemayá with Rite of Spring, including octatonic and pentatonic melodies, trichords, harmonic rhythm, and chromatic sonorities. But I would like to meditate on one moment in Hoag’s article relevant to this poetic and musical analysis.

Hoag is too quick to presume that “what was a regular, common octosyllabic line in the poem has now become a 7/8 bass ostinato in music” (174). As examined before, this motif, although octosyllabic, is more accurately analyzed in its stressed accents. “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé” carries a 2, 4 / 3 accent scheme that could very well omit the first syllabic value of “May” in the first “Mayombe”—making it a seven-syllabic line. Again, Revueltas heard this poem recited out loud, which suggests that the accentual stress on the second syllable in this line would have prominently outshined the first syllable, creating a possible diphthong effect. Revueltas’s hand-written notation of this motif in the manuscript and the ongoing repetition of this motif as rendered as the pervading bass ostinato suggest that Revueltas was more aware of this rhythmic component in the poem than previous scholarship suggests.

Eduardo Contreras Soto (2000) discusses Revueltas’s formation of rhythm as it relates to the closing section of Sensemayá, noting a characteristic pattern of Revueltas’s compositions that is particular to Sensemayá. Revueltas groups rhythmic patterns by first introducing them in the piece one after the other—without melodic or harmonic development—only to then reintroduce them later in the piece to create sonorous density and contrapuntal spontaneity. This spontaneity can be attributed to the accumulation and buildup of these rhythmic patterns throughout the piece (Soto 2000:74). The culmination of contrapuntal rhythmic textures and sounds is observed in Sensemayá, where each section of the orchestra interprets a different rhythmic pattern at the same time in the final section of the piece (Soto 2000).

Additionally, Revueltas plays with time signatures more explicitly from rehearsal number 28 to rehearsal number 35 (Revueltas 1949/1938). The time signatures 7/16 and 7/8 alternate between rehearsal number 28 to rehearsal number 33, where different instruments are assigned to play in either one or the other time signature. This creates a rhythmic alternation that echoes the accentual structures in the poem’s stanzas. To create even more dramatic contrasting variations between meters, the section from rehearsal numbers 33 to 35 convulses between 5/8 and 9/8, offseting the rhythmic patterns. The strings, brass, and woodwinds play equal sixteenth note phrases, which are then followed by glissandos from the strings and the gongs. By creating these irregular meters, the downbeat of each measure strays away from a sustainable and consistent beat; this harkens back to the unstressed beats, the differences of stanzas, the visually and audibly uneven lines, and the repeats of the poem.

The end of the orchestral piece (Figure 11) also speaks to this final dramatic trajectory of music, dance, and rhythm all operating simultaneously. Revueltas expands on this culmination beyond the two rhythmic patterns presented in the poem (“Mayombe—bombe—mayombé” and “sensemayá”). He recreates this in six different rhythmic patterns, presented separately in the beginning of the piece and grouped together in the final measures. The piccolos, oboes, English horns, French horns, clarinets, and first violins are grouped to play long tones in the upper register while the trombones also carry long tones with more varied syncopation. The flutes and bass clarinets play trill-like sixteenth notes; the bassoons, bass, timpani, glockenspiel, and piano play consistent eighth notes; the gourd and tom-tom play sixteenth notes interspersed with eighth notes; and finally, the second violins, violas, and trumpets play the main theme that ties the poem to the orchestral piece: the rhythmic translation of “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé.” In creating these six rhythmic patterns, Revueltas presents a process of translation as recreation that omits many details to conserve the emphasis of the work with added interpolations. The rhythmic complexities herald back to the accentual characteristics of “Sensemayá”—most specifically the “mayombé” meter—but expand and transform this to embed similar and divergent overlapping rhythmic patterns that are also unified in the poem.

Figure 11. Rehearsal no. 37 from Sensemayá musical score (1949)

The Tonalities of Yorùbá

The final section will speak specifically to the pitch and tone in the “Mayombe—bombe—mayombé” motif that Guillén renders in his poem. A critical approach suggested by Agawu considers the tonal and accentual dimensions of language as another point of musico-literary comparison (2003:108). In this case, this approach can be applied to the Yorùbá language incorporated in the poem. An array of scholars including Klaus Wachsmann, David Locke, John Miller Chernoff, and Gerhard Kubik have argued for the direct link between African music studies and the language map of Africa; however, this was an assertion that has led to little active study of these languages (Agawu 2003:107). Agawu underlines the importance of studying African languages for any serious study of African music (most fundamentally for songs). For Agawu, scholars also ought to consider language study as a gateway to understanding the tonal, accentual, acoustic, and phonological levels inherent in the language.

The refrain of “mayombe—bombe—mayombé” derives from Yorùbá, the liturgical language of the religion Palo Monte Mayombe. Notwithstanding many variables affecting African religions in the Caribbean, the Yorùbá language provided the central structural text within which various ethnic and cultural messages could be retained (Murrell 2010:9). Revueltas’s handwritten notation of this very motif, which assigns specific tonal and musical notations to the words, suggests that he could have recognized—and therefore translated—the cultural significance of the mayombero, as well as the literary significance of the mayombero as the primary protagonist in the poem to kill the snake. Just as important, Revueltas translates the musicality of this phrase as it is inherent to Yorùbá language.

The pronunciation of words in Yorùbá language depends on tonal and pitch differences where a different pitch conveys a different word meaning or grammatical distinction. This pitch differentiation is marked by Àmì ohùn tone marks that are applied to the top of the vowel within each syllable of a word or phrase in a primarily tri-tonal mark variation, do-re-mi. Do represents a low falling tone depicted by a grave accent; re represents mid range with a flat tone, depicted by an absence of any accent; and mi is high with a rising tone, depicted by an acute accent. An example would be “Bàtà” (dò dò), defined as “shoe,” and Bàtá (dò mí), a type of drum (the drum performed in the snake rite). Understanding tone marks is essential to properly reading, writing and speaking Yorùbá—although some words may have similar spelling, they may have very different meanings based on the tone marks.

“Mayombe—bombe—mayombé” would be pronounced in a primarily mid-range and flat tone (given the lack of accents) until the acute accent on the final “mayombé,” which creates a higher-pitched tone at the end. Additionally, the assonant repetition of “ombe” in all three words creates a consistent musical and rhythmic pattern—a pattern that is inherent in the language. This phrase alone carries a melodic, tonal, and rhythmic quality—a musical phrase that Revueltas must have also recognized.

Figure 12. Sensemayá, rehearsal no. 11 (Hoag 1987:174)

This musical notation enlivens and strengthens the musicality of the phrase where the “yombe” is stressed more explicitly. This is achieved not only by the accent marks, but also by the longer tonal emphasis on this assonant sound, as exhibited in the longer eighth note form in contrast to the shorter sixteenth note forms. The final “mayombé” is rendered in a more quickened pace—in accented sixteenth notes—that accelerates the syncopation and rhythm of the phrase. By reimagining and recreating this into actual musical notation form, I would suggest that Revueltas goes so far as to enhance the original text form. Because of the inherent musical quality of the tonal language of Yorùbá, this can be even better understood when expressed musically. Thus, the recurring musical theme—introduced by the violins in the beginning measures and played throughout the piece by the violins and trumpets—suggests that Revueltas remained faithful to the original while transforming it according to his musical intuition.

Conclusion

Thinking through these focused examples of both Guillén’s poem and Reveultas’s piece through the framework of translation theory, I have attempted to create more fluidity between these two works. Considering translation as recreation and transformation allows us to conceptualize and analyze this moment of intuitive inspiration that artists of different media experience when sharing their work. When Guillén read “Sensemayá” aloud to Revueltas, it is of little doubt that the musician was inspired by this powerful poem. But by moving beyond the moment of inspiration and considering Revueltas as a translator of Guillén’s poem—and considering Guillén a translator of the snake rite—we begin to shed light on operative aesthetic, social, and political contexts in which a composer and a poet work when translating from one system to the other. Looking at the details of the poem and orchestral piece reflects my aim to dissolve the walls that isolate these art forms, instead building the bridges that are necessary to better understand how these two art forms carry more aesthetic and formulaic overlaps. Guillén and Revueltas are both poets and musicians, and their collaborations make these emerging channels visible.

References

Agawu, Kofi. 2003. Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions. New York: Routledge.

Arnold, Matthew. 1861. On Translating Homer: Three Lectures Given at Oxford (with F.W. Newman’s Reply). London: Milford Oxford University Press.

Augier, Angel. 1965. Nicolas Guillén Estudio Biográfico-Crítico. Ciudad de La Habana: Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba.

Azuela, Alicia. 1993. “El Machete and Frente a Frente: Art Committed to Social Justice in Mexico.” Art Journal 52(1):82–87.

Bartlett, Rosamund. 2003. “Stravinsky’s Russian Origins.” In Cambridge Companion to Stravinsky, edited by Jonathan Cross, 3-18. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Borges, Jorge Luis. 2010. “The Homeric Versions.” In On Writing, translated by Suzanne Jill Levine. New York: Penguin Books. Originally published in 1932.

———. 1964. Labyrinths: Selected Short Stories and Other Writings, edited by Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby. New York: New Directions.

Ellis, Keith. 1983. Cuba’s Nicolas Guillén: Poetry and Ideology. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Garland, Peter. 1991. Sensemayá: In Search of Silvestre Revueltas. Santa Fe: Soundings Press.

Gloag, Kenneth. 2003. “Russian Rites: Petrushka, The Rite of Spring and Les Noces.” In Cambridge Companion to Stravinsky, edited by Jonathan Cross, 79-97. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Guillén, Nicolás. 1967. “Sensemayá.” Sóngoro Cosongo, Motivos de Son, West Indies Ltd., España. Buenos Aires: Editorial Losada, S.A. Originally published in 1934.

———. 1934. “Sensemayá.” In West Indies Ltd. La Habana: Imprenta Ucar, García & Cía.

———. c. 1960. “Sensemayá.” [Recorded by Nicolás Guillén]. El son entero en la voz de Nicolás Guillén. Edited by Jacobo Muchnik. Album text by Rafael Alberti. Buenos Aires: Collección Los Poetas No. 4. Vinyl recording.

———. 1982 [1947]. El son entero: suma poética 1929–1946. Buenos Aires: Editorial Pleamar.

———. 2009. “Sensemayá.” Translated by Roberto Márquez. In The Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry: A Bilingual Anthology, edited by Cecilia Vicuña and Ernesto Livon-Grosman, 221-222. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hess, Carol A. 1997. “Silvestre Revueltas in Republican Spain: Music as Political Utterance.” Latin American Music Review 18(2):278-298.

Hoag, Charles K. 1987. “A Chant for Killing a Snake.” Latin American Music Review 8(2):172–184.

Kristal, Efraín. 2002. Invisible Work. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Kubayanda, Josaphat. 1990. The Poet’s Africa: Africanness in the Poetry of Nicolás Guillén and Aimé Césaire. Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Murrell, Nathaniel Samuel. 2010. Afro-Caribbean Religions. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Pellicer, Carlos. 1973. Recordando al Maestro. Collección testimonios de Fondo: Silvestre Revueltas. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Revueltas, Eugenia. 2002. “La Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios y Silvestre Revueltas.” In Diálogo de Resplandores: Carlos Chavez y Silvestre Revueltas, edited by Yael Bitrán and Ricardo Miranda, 172-181. Mexico City: Conaculta.

Revueltas, Silvestre. 1949 [1938]. Sensemayá. New York: G. Schirmer, Inc.

Soto, Eduardo Contreras. 2002. Silvestre Revueltas: Baile, Duelo y Son. Mexico: Conaculto.

Stevenson, Robert. 1980. “Revueltas, Silvestre.” In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. London: Macmillan Publishers.

Zohn-Muldoon, Ricardo. 1998. “The Song of the Snake: Silvestre Revueltas’ Sensemayá.” Latin American Music Review 19(2):133–159.

- 1. See the Matthew Arnold v. Francis W. Newman debate on theory and practice of translating Homer in Matthew Arnold’s On Translating Homer: Three Lectures Given at Oxford (with F.W. Newman’s Reply), (London: Millford Oxford University Press, 1861).

- 2. Although not an inclusive list, the primary short stories and essays that suggest these issues of translation include “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” “Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote,” “The Circular Ruins,” “Averroes’ Search,” and “The Immortal” (Labyrinths 1964).

- 3. Murrell enumerates more common symbolic names such as: Palo Monte Mayombe, Congas Reglas, Reglas de Palo, Regla de Conga, Regla de Palo Monte, Las Reglas de Conga, Palo Kimbisa, and Santo Cristo Buen Viaje (2010:136).

- 4. This analysis came out of a discussion with Steven Loza, UCLA Department of Ethnomusicology, in May 2013.

- 5. This vinyl recording, El son entero en la voz de Nicolás Guillén, should not be confused with El son entero (1947), a collection of poems that Guillén published in Buenos Aires.

- 6. For a more intimate understanding of the friendship Guillén and Alberti shared, Centro Virtual Cervantes has posted online personal epistolary correspondences between the two poets (1959–1964): http://cvc.cervantes.es/actcult/alberti/sobre_poeta/sobre08.htm. Epistolario de Nicolás Guillén (2002) by Alexander Pérez Heredia and Rafael Alberti en Cuba (1990) by Angel Augier study this relationship between the poets in more detail.

- 7. All translations from citations in Spanish are my own.

- 8. a. b. As discussed in Peter Garland’s 1991 article.