The Culture-Bearers vs. The National Institute of Culture: (Mis)Representations of Panamanian Folklore

In the community of Bugabita, Panamá, the townspeople preserve and guard a tradition of moros y cristianos known locally as la danza Bugabita. Recent separation from the Catholic Church contributed to the disappearance of social contexts and conditions for the performance of this traditional dance-drama. Its productions now rely on community funding and support. Largely unknown to communities outside of Bugabita due to its guarded protection, and faced with temporary discontinuation due to financial burdens, cultural promoters looked for ways to share, stimulate, and revitalize the legacy of this tradition. Governmental institutions, particularly The National Institute of Culture known by its acronym INAC, stepped in with a mission of preservation in order to overcome the possible abandonment of this particular tradition.

INAC’s presentations of la danza Bugabita emphasize the performative as opposed to the textual, much to the dismay of the community of Bugabita. The processes of folklorization used to adapt this local practice to cosmopolitan aesthetics reworked moros y cristianos into a new presentational context. Such rifts and exploitation have further separated the two factions, resulting in the community having even less control over their own cultural property. Based on interviews and participant observation obtained during my fieldwork in Panamá, this paper will focus on two case studies, a 2008 performance at the University of Costa Rica and a 2013 regional performance in Volcan, Panamá, in order to describe the departures of characterization and meaning between institutional sponsorship and non-governmental initiatives. These case studies illuminate ethical issues of reclaiming, resignifying, and performing tradition.

Academics from various disciplinary backgrounds have observed, documented, and analyzed festivals in very different geographical and historical contexts. From these particular contexts, a set of formal characteristics have emerged across these varying disciplinary perspectives and are now commonly used in the study of festivals within the humanities. Anthropologists, ethnomusicologists, folklorists, and performance scholars, among others, often investigate the interaction of ritual genres such as festivals, with diverse discourses including identity, gender, history, religion, commodification, globalization, tourism, political economies and power exchanges, as well as other numerous perspectives of festival practices observed in varying societies. While these two case studies touch on each of these discourses, due to the nature of this short presentation, I am limiting my theoretical framework to the ethical concerns that the community of Bugabita has experienced with national governmental intervention from their own perspective. According to Kay Shelemay, “[m]ost discussions of ethics have tended to focus on interpersonal relations during and after fieldwork, and only incidentally to address the impact on the musical tradition itself.”[1] Let me lead you chronologically through my experiences in Panamá that made this ethical consideration so plainly evident.

After a series of extremely serendipitous events, I procured an invitation to be hosted by Don Ray Williams, the Warden of David, Panamá, an ambassador position of the U.S. embassy, and his Panamanian family including his wife, Lilliam, and her daughter, Natalie. After arriving, they all expressed how eager they were to help in any way that they could with my research project. So what exactly was my project?, they wanted to know. I explained that I was going to be writing my dissertation on la danza Bugabita. After explaining the little that I then knew about it, they all just sort of stared at me. None of them had heard of such a thing. I then showed my host family a recent, local newspaper article I had found on the dance, the first line of which reads, “Have you heard about the dance of the Moors and Christians?”[2] It looked like we were all going to be introduced to something new.

Figure 1: Newspaper article by Cristhian Pérez, “Mensaje de cristiandad: Así es la ‘Danza Bugabita’”

My host family had already proven that “[m]any people in Chiriqui don’t even know [la danza Bugabita] exists; the people [of the community of Bugabita] close the doors,”[3] as I learned from Lilia, the matriarch of Bugabita, later that week.

The very next day I went to INAC’s regional headquarters in David, had a short interview with its director Mr. Gregorio Gonzalez who admittedly gave me a superficial explanation of the dance, and was given a long list of names of people who knew about la danza Bugabita. Mr. Gonzalez had passingly said that I might have a hard time getting anybody to talk about it. While following his leads, the name Ángela Requena kept surfacing. I was eventually able to contact her, and she offered to have me come meet her at work during her break. So my host family and I drove to the elementary school where she works, and she began by asking us about ourselves. Seemingly satisfied with our answers, she proceeded to tell us about the dance-drama, pausing only when her husband arrived with their camera that contained pictures and videos of their most recent production of la danza Bugabita. They were co-directors of the troupe, and the husband one of the performers. Before we left she gave me a copy of her thesis in folklore about the dance-drama that she had just finished in 2011, and invited all of us to her house for a longer, more thorough interview on Sunday afternoon.

After our interview on Sunday, she accompanied me to the homes of several members of the group, the musicians’ homes, and other important community members. With her present, and her vouching for me as someone “who is truly interested in the tradition and its meaning,”[4] all but one agreed to talk with me. Through these interactions, although greatly simplified here for time’s sake, I learned that la danza Bugabita represents a struggle between two factions: the Moors and the Christians, both battling for relics of Jesus Christ. The Moorish soldiers, led by Almirante Balan, the Moorish king, steal the relics from the Christians and deface them. The Christians are then led in battle by Carlos Magno (Carlomagno), commonly known to us as the historic figure Charlemagne, who try to recover the relics. Eighteen males participate, as females are prohibited from formally participating onstage, and include a Christian king, a Moorish king, six soldiers each of Christians and Moors, one angel, the devil, and two musicians (an accordionist and percussionist).

Figure 2: La Danza Bugabita. Photo by Heather Paudler.

The dance-drama incorporates five songs, line dancing, spoken dialogue, a ritualized baptism, a zapateo, and musically accompanied mock sword battles divided into three acts comprised of thirteen choreographed scenes. While religious expressions of folk Catholicism are traditions that are themselves historically changing and reinvented over time, even severed from its ties with the Catholic Church, la danza Bugabita maintains the same choreographic scenes, music, costumes, and text that have been in place for over 100 years of its existence in Bugabita. Any changes that are proposed are discussed by the group members and then brought before the community. Concerning change, Ms. Requena states, “I can’t say yes if the group doesn’t accept it. It’s no, no, no; it’s not okay if the community says no.”[5]

A word that came up with great frequency, both in the thesis and in the interviews, was receloso, a word that means suspicious or mistrustful. That night I asked Ms. Requena, “In your opinion, why are the residents of this town so guarded and a little suspicious and mistrustful of their manners and traditions?”[6] She responded,

Well, according to my opinion – based on an investigation I’ve made for years with the help of my husband and [members of the community of Bugabita] – they are suspicious because in this country, specifically in this country, there are people who don’t share our point of view. They take something beautiful and they want to benefit from it, be it personally or economically. That is to say, to lift their own success. Many people have arrived here and have deceived the community. They have offered their help, that they’re going to do this or that, but don’t. … It’s a taboo. That’s why [our community] began to guard this tradition, to the point that now this same tradition could be lost.[7]

Surprised, I pressed for a little more information and Ms. Requena explained:

Some years ago, I forget, I think in El Salvador or Honduras, I don’t know what country it was, where Martín Serrano put together an event that resulted in the presentation of the tradition at the Central American level. La danza de Bugabita went to that place, but none of us went because nobody ever advised us that it was going![8]

After an audible sigh, she continued, “Imagine that it was taken to the level of a Central American presentation and they didn’t care how they performed this tradition. That’s why the town guards it so much.”[9] With a name and a general Central American location, over the next few months as a tangential interest, I pieced together what had happened at this event.

Professor Martín Serrano of Centro Superior de Bellas Artes y Folklore de David, an institution of higher education under the control of INAC, used money from a governmentally funded folklore project to present la danza Bugabita at the University of Costa Rica in 2008 as part of an event that brought together several Central American folkloric traditions. Serrano did not consult the community about his venture, nor did he study the tradition in depth before taking his personal troupe, not that of the community, to Costa Rica. Instead of conducting research himself, he paid one community member and former participant of la danza Bugabita to take part in his production and train the rest of INAC’s dancers. Three of the thirteen scenes were chosen to be presented, none of which included singing, and all of which focused on the mock sword fighting, reducing the nearly two hour performance to a mere 15 minutes. Serrano’s production utilized only eight male characters, including only the two kings; two Christian soldiers and two Moorish soldiers; and, not one, but two, devils. It is important to note that the devil is the only character without any speaking parts, and the only character that interacts with the audience.

Figure 3: The Devil in La Danza Bugabita. Photo by Heather Paudler.

After learning about this presentation, during another interview last fall with Ms. Requena, I casually inquired a little more about this event and how it affected the community. She said,

In this presentation in Costa Rica: two devils!? It wasn’t a presentation of the dance, it was madness! It was of a totally different color. The community was upset. … The community shut up and didn’t give out any information [regarding the tradition] because Bugabita completely closed down.[10]

We also learned Ms. Requena’s perspective on the community member who went to Costa Rica, which Don summarized on his blog by writing, “One of the Bugabita residents, that has participated in past events, no longer supports the group and prefers to sell his knowledge to groups in Costa Rica.”[11] I believed this is where this line of inquiry was going to stop for me. I had no interest in researching or writing about the one production in Costa Rica, and I had learned why a community that loved and lived this tradition so much had ambivalent feelings toward sharing it.

In mid-September I had already set up another interview with Professor Requena on a Saturday morning, and had warned her that I might rob her of her whole day with the amount of questions that I had. In the meantime, I was trying to locate a book and an article without any luck at the public library in David. Since the publisher of the book was INAC and the journal, while now out of print, had been funded and published by the government, I thought I might see if anybody at INAC could help me find these sources. When we walked in, I was immediately recognized as the girl who studies la danza Bugabita. While they did not have the book, they called a museum and another library in order to locate it, and were able to provide me with a digital copy of the journal article.

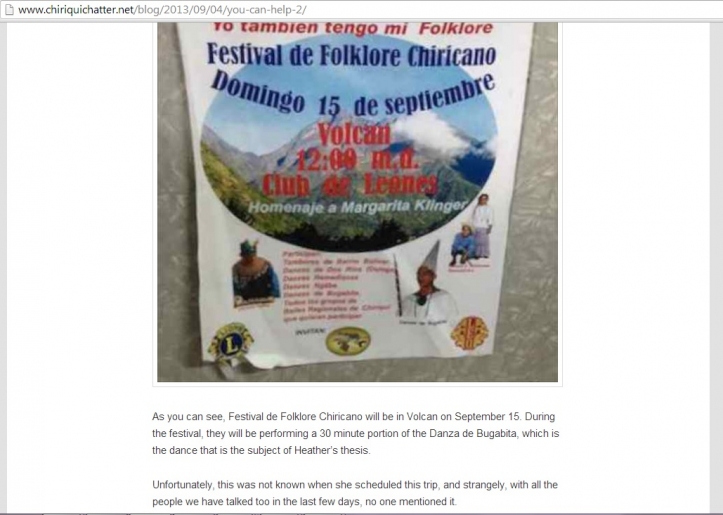

After the employees started leaving the main office and I was preparing to leave, Don, Natalie, and I noticed a poster on one of the classroom doors. Both Don and I took a picture of it, and the woman at the front desk said they were planning on performing a 30 minute segment of la danza Bugabita. As we walked back to the car, the three of us talked about our confusion as to why nobody in INAC had mentioned it to us. In a post on Don’s blog he uploaded the picture and wrote,

As you can see, Festival de Folklore Chiricano will be in Volcan on September 15. During the festival, they will be performing a 30 minute portion of the Danza de Bugabita, which is the dance that is the subject of Heather’s thesis. Unfortunately, this was not known when she scheduled this trip, and strangely, with all the people we have talked to in the last few days, no one mentioned it.[12]

Figure 4: Poster at INAC. Don Ray Williams, www.chiriquichatter.net/blog/

Peculiar as we thought it was, I quickly added a few questions to the ones I had already planned out for Ms. Requena regarding this presentation and started seriously thinking about extending my trip so I could stay and catch it on camera. Maybe now I’d be able to see an actual performance and not just rehearsals or short portions that I had questions about. Perhaps now I’d see a live presentation, even if it wasn’t in its entirety.

I prepared the following questions for the interview: “Can you talk about the preparation of the presentation of the dance in Volcan on September 15th , 2013? Will they be realized with 18 members (both musicians and dancers)? The duration of the dance in this presentation is only 30 minutes. What parts of the dance are you going to perform? Why these parts of the dance?” On Saturday, about two and a half hours into our discussion of the dance-drama, I got to this section of questions, and this is what unfolded:

HP: [I was only able to get out...] Can you talk about the preparation of the presentation of the dance in Volcan on September 15th…? [...before I looked up and noticed the confusion on her face and said] We saw the poster in INAC.

ÁR: The National Institute of Culture? [she responded impudently]

HP: Here, I have it for you to see. [After discussing it for a while, just to be clear, I asked] So, then, you had no idea?

ÁR: No, I didn’t have the slightest idea. I had no idea at all about this presentation.

HP: Ay... Are you going?

ÁR: [laughter][13]

In a post on Don’s blog, he wrote,

Saturday, we went to Bugabita so that Heather could continue her interviews with the custodians and experts of the Bugabita Dance…We did learn that the event in Volcan was not sanctioned and the event was not even known to the custodians of the dance in Bugabita. They had not been consulted and had not been requested to assist in the event.[14]

This poster revealed a more recent case of governmental intervention, and one that I learned was ongoing. While Ms. Requena did not know about this particular presentation, she did inform us that INAC, under Professor Gregorio Gonzalez, (the same man that had helped me find Ms. Requena, helped me find sources through INAC, and had neglected to tell me of his performance while I was at INAC), frequently directs la danza Bugibita at small regional festivals. In his versions, the performers are a group of children that includes girls, and often these children are paid, whether reimbursement or incentive is open for debate. These performances are not condoned by the community of Bugabita, save the parents of the few Bugabeña children that participate, which begs the question, what is INAC’s purpose of presenting this tradition in this manner?

The National Institute of Culture was created when the National Council on Legislation passed Law #63 of June 6, 1974. Its mission statement claims that

The National Institute of Culture is an official agency, created by legal mandate in order to guide, promote, coordinate, manage, and promote cultural activities throughout the country, and to protect, rescue, disseminate, and preserve the cultural heritage and history of our country.[15]

Their vision statement claims

[t]o gather all of our cultural heritage and disseminate our identity, the values of the people, the Panamanian art and traditions, like our folklore, so that future generations know the cultural background and the historical development of our national republic [and] to provide mechanisms for cultural integration, plans designed in favor of socio-cultural development; thus contributing to forge a solid foundation for a dynamic and thriving society in a modern and globalized world.[16]

INAC’s objective is “[t]o guide, encourage, coordinate, and direct the cultural activities in the country.”[17]

Particularly lacking from any of its objectives and mission statements is how the institute intends to realize their vision. According to the matriarch of Bugabita, Lilia, this equates to smoke in mirrors, or in her words, “grand gestures without backbone.”[18] Moreover, as an important adjunct to INAC’s scholarly mission of the (re)discovery, interpretation, and perpetuation of musics, dances, art, festivals, and all other Panamian folklore, the institution manages 23 centers for teaching various art forms; organizes competitions; offers limited literary and artistic scholarships for scholars; manages three theaters, including the National Theatre; coordinates the National Symphony Orchestra and the National Ballet; and also maintains 18 museums. INAC has 13 regional offices, including one in the city of David, province of Chiriquí, about 40 minutes from Bugabita.[19]

As understood from INAC’s philosophy, a basic tenant of their platform is the preservation of tradition. Shelemay draws attention to the process of preservation stating,

If any aspect of the ethnomusicologist’s entry into the transmission process is generally acknowledged, it is the presumption that ethnomusicological activity works on one level to preserve. While the ethic of preservation was long an unquestioned part of the ethnographic process, and older paradigms led earlier scholars to seek out and study certain traditions since they would otherwise “be lost,” it seems clear that the very process of studying any musical tradition is tantamount to participating in an act of preservation.[20]

It is precisely this process of studying the tradition of la danza Bugabita that the culture-bearers claim INAC has neglected to do, subsequently perverting the tradition rather than preserving it.

La danza Bugabita is intrinsically tied to the identity of Bugabeñas. According to Ms. Requena, “It’s our way of being. Whenever the group presents, the first thing that they say is ‘this is the town of Bugabita.’”[21] From various interviews and discussions with the residents of Bugabita, I’ve learned that the central polemic among residents regarding performance and INAC’s role in transmitting tradition hinges largely on issues of authenticity. The culture-bearers do not question whether INAC should be active in preserving the tradition, but rather how closely they should adhere to historical precedent. Ms. Requena laments,

Sadly, the government has something bad: that if you don’t advertise, if you don’t sell it … [long pause]. It’s good to sell – but they want to sell an image that isn’t it. With respect to the dance, they want to make a dance that is to say “beautiful” in front of the audience. And the town doesn’t want that. The town wants a dance that is beautiful in its love and in its tradition. It’s not about what they wear… They want to sell something that is really a lie. It’s a lie.[22]

As such, Bugabeñas do not view INAC’s presentations as a context for nurturing their tradition.

These perceived breaches in authenticity have led to INAC’s reinvention of the tradition, one that is loosely adapted from local practices to be put on the stage in a presentational context, formally creating two separate factions of la danza Bugabita that do not communicate with one another, and that represent two completely different pictures. Rather than INAC’s interventions supporting continuity in the tradition, they have engendered great changes. The only form that can be seen by outsiders is actually the performance genre that emerged in the wake of INAC’s initiatives, which raises Shelemay’s “slippery issues in the ethics of ethnographic research”[23] and the fundamental issues related to the production, interpretation, ownership, and remuneration of festival as a commodified product.

Many culture-bearers view the misrepresentations of national government and institutional initiatives as imposing neo-colonial policies through their exploitations of la danza Bugabita, resulting in an uneven power dynamic that renders even less control for the community over their own cultural property. Community members interpret INAC’s irresponsible preservation and transmission of tradition as an ethical problem created through a lack of mediation and active relationship to the tradition itself. Cut off from any communication with the culture-bearers of Bugabita, INAC’s festivals hardly function as platforms for gaining back social spaces for the musical tradition, nor does it serve to create new contexts to share, experience, nurture, promote, and revitalize the legacy of this musical tradition and culture. Thus, INAC’s versions do not instill the tradition’s ascribed values into society. To add further insult to injury, the national government does financially support la danza Bugabita, sponsoring festivals and paying participants, but it is not the Bugabeñas that receive the support, but rather those without a contract with the carriers of the tradition itself who participate in the perceived inauthentic governmental initiatives.

As a musicology student, I am aware of a certain code of ethical behavior that urges us as scholars to aspire to responsible behavior, to stimulate active cooperation between scholars and performers, to abide by social responsibility, and even the relatively new concept regarding appropriate reciprocity. Immersed in the tradition of la danza Bugabita, I also learned that not all initiatives adhere to such guidelines. So rather than serve as a warning, by discussing the community’s problems and concerns, I am now keenly aware of my role in the process of preservation and transmission. These conversations acknowledge the reality of the transmission process within the community and within the realm of governmental sponsorship, providing ethical guidelines for how I, personally, should navigate this tradition and for how I use the information I gather, both underlining my own responsibility in this tradition.

References

Castiellero Calvo, Alfredo, ed. Historia General de Panama, 3 vols. Panama City: Comité Nacional del Centenario de la República de Panamá, 2004.

Cheville, Lila R. and Richard A. Cheville. Festivals and Dances of Panama. Panama: s.n., 1977.

Fonseca, Lilia. Interview with Heather Paudler. Personal interview. Bugabita, 14 April, 2013.

Gonzalez, Gregorio. Interview with Heather Paudler. Personal interview. David, 4 September, 2013.

Mantilla Tascón, Antonio. “Los viajes de Julián Gutiérrez al Golfo de Urabá.” Anuario de Estudios Americanos de la Universidad de Sevilla 16, 1/10 (1945): 181-263.

Miró, Rodrigo. “Noticias sobre el Teatro en Panamá.” Revista Lotería 50 (1971): 28-36.

Murillo, I. “Teatro Religioso en el Distrito de Pesé con Antecedentes en el Teatro Medieval Español.” Tesis para la obtención del Título de Licenciado en Español. Universidad de Panamá, Panamá, 1995.

Osorio Osorio, Alberto. -1903. vols. Panamá, Rep. de Panamá: [s.n.], 1988.

Oviero, Ramón, and Héctor Rodríguez C. . [Panamá]: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Dirección Nacional del Patrimonio Histórico, 1 .

Pérez, Christhian. “Mensaje de cristiandad: Así es la ‘Danza Bugabita.’” Mi Diario. 19 April 2012. Accessed 30 March 2013. bloga.prensa.com/proyecto-folclore/de-moros-y-cristianos/

Requena Otero, Ángela Maria. “Las danzas de moros y cristianos del poblado de Bugabita Arriba, corregimiento de la Concepcion, distrito de Bugaba, provincial de Chiriquí.” Thesis, Insituto Nacional de Cultura Centro de Estudios Superiores de Bella Artes y Folklore de David, Seccion de Folklore, David, 2011.

_____. Interview with Heather Paudler. Personal interview. Bugabita, 14 April, 2013 and 6 and 8 September, 2013.

Shelemay, Kay Kaufman. “Crossing Boundaries in Music and Musical Scholarship: A Perspective from Ethnomusicology.” The Musical Quarterly 80/1 (Spring 1996): 13-30.

_____. “The Ethnomusicologist and the Transmission of Tradition.” The Journal of Musicology 14/1 (Winter 1996): 35-51.

Williams, Don Ray. Chiriquí Chatter Blog. www.chiriquichatter.net/blog/

[1] Kay Kaufman Shelemay, “The Ethnomusicologist and the Transmission of Tradition,” The Journal of Musicology 14/1 (Winter 1996): 39.

[2] Cristhian Pérez, “Mensaje de cristiandad: Así es la ‘Danza Bugabita,’” Mi Diario, 19 April 2012, accessed 30 March 2013, bloga.prensa.com/proyecto-folclore/de-moros-y-cristianos/

[3] Lilia Fonseca, personal interview with Heather Paudler, Bugabita, April 14, 2013.

[4] Ángela Maria Requena Otero, in personal interview between Lilia Fonseca and Heather Paudler, Bugabita, 14 April, 2013.

[5] Ángela Maria Requena Otero, personal interview with Heather Paudler, Bugabita, 8 September, 2013.

[6] Requena, personal interview with Heather Paudler, Bugabita, 14 April, 2013.

[7] Requena, personal interview with Heather Paudler, Bugabita, 14 April, 2013.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Requena, personal interview with Heather Paudler, Bugabita, 8 September, 2013.

[11] Don Ray Williams, Chiriqui Chatter Blog, www.chiriquichatter.net/blog/

[12] Williams, Chiriqui Chatter Blog, www.chiriquichatter.net/blog/

[13] Requena, personal interview with Heather Paudler, Bugabita, 8 September, 2013.

[14] Williams, Chiriqui Chatter Blog, www.chiriquichatter.net/blog/

[15] See www.inac.gob.pa/

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Fonseca, personal interview with Heather Paudler, Bugabita, 14 April 2013.

[19] See www.inac.gob.pa/

[20] Shelemay, “The Ethnomusicologist and the Transmission of Tradition,” 46-47.

[21] Requena, personal interview with Heather Paudler, Bugabita, 8 September 2013.

[22] Requena, personal interview with Heather Paudler, Bugabita, 8 September 2013.

[23] Shelemay, “The Ethnomusicologist and the Transmission of Tradition,” 39.