Woody Guthrie: American Radical

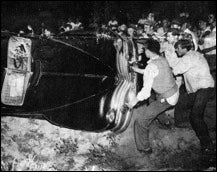

In Peekskill, New York, in the summer of 1949, Woody Guthrie led a group of terrified folksingers in a desperate rendition of “We Shall Not Be Moved” as their car crawled down a bumpy country lane. They were coming from an outdoor concert benefitting the Civil Rights Congress, with Guthrie, Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger, and others performing in spite of thinly veiled threats from the local police and a blockade of protests by American Legionnaires and plainclothes Klansmen. The concert, attended by tens of thousands of Civil Rights supporters, proceeded with minimal disruption despite the constant presence of a noisy police helicopter trying to drown out the music. It was on the way home that the trouble began. The local police deliberately directed a convoy of musicians and concert-goers into an ambush: the long, lonely country lane was lined with Klansmen and youths fired with anti-communist enthusiasm who pummeled the passing cars with stones, breaking windows and injuring hundreds. Enduring this violent gauntlet, Guthrie’s car resounded with song and fear thinly masked in bravado. Guthrie told jokes to keep up morale: “Anybody got a rock? There’s a window back here that needs to be opened!” (160). Passengers pinned clothing over the windows to protect themselves from shards of shattered glass; Guthrie pinned up, in the midst of the anti-communist riot, a red shirt.

In Peekskill, New York, in the summer of 1949, Woody Guthrie led a group of terrified folksingers in a desperate rendition of “We Shall Not Be Moved” as their car crawled down a bumpy country lane. They were coming from an outdoor concert benefitting the Civil Rights Congress, with Guthrie, Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger, and others performing in spite of thinly veiled threats from the local police and a blockade of protests by American Legionnaires and plainclothes Klansmen. The concert, attended by tens of thousands of Civil Rights supporters, proceeded with minimal disruption despite the constant presence of a noisy police helicopter trying to drown out the music. It was on the way home that the trouble began. The local police deliberately directed a convoy of musicians and concert-goers into an ambush: the long, lonely country lane was lined with Klansmen and youths fired with anti-communist enthusiasm who pummeled the passing cars with stones, breaking windows and injuring hundreds. Enduring this violent gauntlet, Guthrie’s car resounded with song and fear thinly masked in bravado. Guthrie told jokes to keep up morale: “Anybody got a rock? There’s a window back here that needs to be opened!” (160). Passengers pinned clothing over the windows to protect themselves from shards of shattered glass; Guthrie pinned up, in the midst of the anti-communist riot, a red shirt.

The Peekskill riots demonstrate the politically fraught atmosphere of Guthrie’s time and the multivalent role that music played in cultural combat. To the local police, Guthrie and Robeson’s music was a loud symbol of communism and racial equality, a sonic threat so potent it had to be countered by the sound of helicopters. To the violent protesters, it was an anti-American insult that inspired hatred. To the concert-goers, it was a locus of solidarity worth risking bodily harm to hear and, later, in the embattled cars and buses, a font of collective courage and a defense against flung stone. The incident also crystallized typical aspects of Guthrie’s character in a time of crisis: his fierce commitment to the radical cause and the plucky folksiness he employed strategically in its support.

Figures 1 and 2: 1949 benefit concert for the Civil Rights Congress in Peekskill, NY, and the ensuing riots.

In the weeks following the Peekskill riots, Guthrie wrote some of the angriest, most defiant songs of his career, railing against the bigotry of his assailants. His song “Peekskill Golfing Grounds” vividly recalls the violence of their rhetoric:

I’ve never heard such cusswords as they spit from off their lips,

I just stood and watched their eyes blare as they walked a dozen trips.

Jew bastard. Wop. Hey nigger. Kike and Commy. And, their lungs

Sounded like a boiling snake den with a million poison tongues.

(163)

But on the manuscript of another song, written from the point of view of an impressionable youth who participates in the attack against the folksingers before recanting his prejudice in jail, Guthrie wrote beneath his signature, “I was that kid” (164). Will Kaufman’s book Woody Guthrie: American Radical recounts Guthrie’s remarkable process of transformation from a middle-class, casually racist Oklahoma youth to the vehemently antiracist, politically engaged class warrior of his latter years. Kaufman’s meticulously researched, highly readable text is a biography of sorts, one that stays focused on Guthrie’s political life as a songwriter, poet, novelist, newspaper columnist, radio personality, and prolific correspondent. This subject makes for an engaging story full of twists and turns, comical and poignant anecdotes, and a colorful supporting cast of musicians, activists, and folklorists. Kaufman is writing against the popular, institutionalized memory of Guthrie as the benevolent Okie who wrote the patriotic anthem “This Land is Your Land” as well as the image of the roguish man-of-the-road free from personal responsibility embraced by the nascent folk music revival. Instead, he posits Guthrie as a thoughtful, mischievous artist who slyly mobilized folk music and a folksy persona in support of his subtly shifting political ideology. In Kaufman’s words, American Radical is “an entire book devoted to the radical Guthrie […]: a book about a political awakening and its aftermath; a book that would uncover and reclaim the obsessive thinker and fitful strategist practically buried in the romantic celebrations of the Dust Bowl Troubadour” (xxi). Far from a leftwing hagiography, though, Kaufman pulls no punches in describing Guthrie’s personal and political contradictions:

He could be selfish, petulant, bitchy, and snide—and insufferably self-righteous. He climbed on the backs of women, using them and deserting them, pregnant or otherwise; he climbed on the backs of friends. He borrowed guitars and never gave them back. He was a racist into his young adulthood; he neglected his first wife and their children; he could be violent; he never retracted his fondness for Stalin. (xxi)

What emerges is a fascinatingly human portrait of a musician and activist searching for political footing in the sweeping tides of the mid-20th century, pushed and pulled by the changing currents of his time and struggling to be heard above the waves.

Guthrie empathized with the plight of the working poor from a young age, a sentiment that jelled into socialism after witnessing the mistreatment and harsh living conditions of Oklahoma Dust Bowlers who migrated to California in search of work. This commitment to socialist ideology would last his lifetime. What carries Kaufman’s narrative is his examination of Guthrie’s development in this and a number of other social issues. For example, Guthrie’s early broadcasts on KFVD Radio in California included several songs and jokes that were quite plainly racist. After singing Uncle Dave Macon’s patently offensive “Run, Nigger, Run” on his show, he received a letter of polite protest from a local African-American college student. Guthrie read the letter on air the following day and dramatically tore up the offending songsheet in front of the microphone, swearing never to utter that racist epithet ever again. From this epiphanic moment, he developed deeply held feelings of solidarity with people of color based on his own liminally white status as an Okie migrant, the same solidarity that led him to stand proudly by Paul Robeson at the Peekskill benefit for the Civil Rights Congress.

A somewhat subtler political development concerns Guthrie’s stance on American intervention in WWII. Despite Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s apparently populist platform, Guthrie (and the Communist Party of the USA) opposed his initial candidacy. With shrewd analysis couched in typically folksy grammar and wordplay, he mocked FDR’s New Deal relief program in his weekly column “Woody Sez” for People’s World, the West Coast’s communist daily:

Here’s a Definition for Relief:

Relief (noun): It is 2 people and one of them has accumulated the property of both; and then poses as some sort of a “giver”—when in reality he is only giving back a little at a time, the Life that he took at a single grab or two…

Most like a poker game where the cards is marked—and set and shuffled and “dealt,” and timed, and framed, and organized and arranged to “relieve” you of what you got—and then turned around and gives you a mess of beans in exchange for your Freedom—and then make a big speech or two about it and call if “Relief.”

They first relieve you of what you got, then “Relief” you for what you get. (22)

As Adolph Hitler began annexations in Europe, Guthrie was more concerned with the fight against fascism at home in the form of police brutality. His stance on the war in Europe was further complicated by Hitler’s infamous non-aggression pact with Joseph Stalin, a figure who for Guthrie would never lose his sheen of idealism. According to Kaufman, Guthrie’s hopes for the communist Soviet Union influenced this 1941 anti-interventionist songbook scribbling:

And underneath their noses

Their life is lent and leased

To wars across the ocean

To murder o’er the sea –

To fight and die on foreign soil

To save – democracy (?) (53)

It was at this time that Guthrie first attracted negative attention from the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Kaufman characterizes Guthrie’s political stance as one shivering with untenability: he hated fascism at home and in Germany, but his idealistic hopes for the Soviet Union forced him to reject US intervention. Ultimately, Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union erased this paradox. Guthrie joined the Merchant Marines and quickly began writing pro-war anthems, including these rather bloodthirsty lines from his collection “War Songs are Work Songs”:

I’ll bomb their towns and bomb their cities

Sink their ships beneath the tides

I’ll win this war, but till I do, babe,

I could not be satisfied. (xxi)

Kaufman repeatedly cites Guthrie’s unwavering support of Stalin as an ugly blemish on his political record; it is unsurprising, then, that after WWII he returned to a pro-peace, anti-interventionist stance during the Cold War and its proxies. It is exactly these contradictions and complications that make Guthrie such an enthralling subject under Kaufman’s pen.

Of particular interest to ethnomusicologists will be Kaufman’s description of the discussion between Charles Seeger, Alan Lomax, Henry Cowell, and others regarding what type of music would make an appropriate soundtrack to the communist movement in America. Loyal to Karl Marx’s aspersion of the countryside and his edict that “the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living” (Marx 1852), Charles Seeger initially favored experimental modernism. He wrote that folk songs were not “suitable to the revolutionary movement. Many of them are complacent, melancholy, defeatist--originally intended to make slaves endure their lot--pretty, but not the stuff for a militant proletariat to feed upon” (35). Reflecting on a particularly complicated and un-catchy piece of revolutionary music, Seeger would later recall drolly, “There’s one on Chiang Kai-shek in the five tone scale in five-four time with five-measure phrases, in which I call Chiang Kai-shek a tyrant and a murderer and everything else. We really did sing away, but it didn’t catch on very much” (36).

Seeger quickly abandoned this position to join John and Alan Lomax in embracing the potential of country folk music to be a “weapon in the class struggle” (37). Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt’s fondness for traditional music aided their quest to document American folk music practices. Alan Lomax set about recording Woody Guthrie with characteristic enthusiasm, seeing in him an authentic representative of the American folk and a voice of genuine working class advocacy. For his part, Guthrie did his best to negotiate the rural persona expected of him with his own increasingly sophisticated political radicalism. Moses Asch, himself a prolific recorder of Guthrie’s music, described the early Lomax-Guthrie recordings: “If you listen to those Library of Congress recordings, you can hear all the put-on [Guthrie] wanted to give Alan Lomax. This is the actor acting out the role of the folksinger from Oklahoma” (41). Lomax wrote frequently to the politicized Almanac Singers, a collaboration of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger among many others, telling them: “What you are doing is one of the most important things that could possibly be done in the field of American music. You are introducing folk songs from the countryside to a new city audience, and you are learning how to do it” (66). History has confirmed the efficacy of folk and gospel music in supporting American social movements, illuminating the negotiation of country and urban, old and new, art and folk music that is often involved in political music-making around the world.

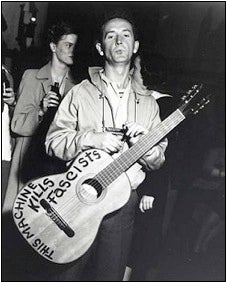

Figure 3: Guthrie’s guitar was an ally in his political fight.

Although Kaufman is himself a musician and apparently a frequent performer of Guthrie’s music, his book includes unfortunately little discussion of how the musical qualities of Guthrie’s oeuvre interacted with his radical politics. Where did Guthrie’s melodies come from, and why did he write them the way he did? Why did he play guitar when he was also a proficient player of the fiddle and banjo? Guthrie often borrowed melodies from existing folk, gospel, and popular songs. In addition to ensuring instant audience familiarity, this tactic sometimes also allowed for intertextual musical commentary on the original song he borrowed from, as either parody or tribute. Guthrie’s famous “This Land is Your Land,” for example, borrowed the melody of an existing gospel song recorded by the Carter family and its text responded to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” which Guthrie deemed politically complacent. Guthrie’s guitar-playing was deliberately rough and he often stuck stubbornly to a maximum of three chords per song even when the melody obviously demanded a dominant second in addition to diatonic I, IV, and V chords. This approach served to enhance his aura of folk authenticity and cement the authority of his working-class message. The straightforward combination of bass notes with open chords (that old ‘boom chuck’ rhythm) provided a simple and open canvas on which to write his political message. By Guthrie’s time, the guitar had eclipsed the banjo in popularity and was significantly cheaper and easier to find in mail order catalogues. The highly accessible, mass-manufactured nature of the guitar would have appealed to Guthrie’s populist sentiments, managing to combine countryside rusticity with technological modernity. For Guthrie, the guitar was a ‘machine;’ a weapon against fascism. Kaufman succeeds in convincing the reader that Guthrie was an exceptionally thoughtful, considered songwriter; it only stands to reason that his musical choices were equally strategic.

In spite of this oversight, Kaufman roundly succeeds in his task of unearthing the radical Woody Guthrie. At times, he is a great storyteller, vividly relating incidents such as the Peekskill riots and poignantly illustrating the way Guthrie channeled his grief over a lost daughter into political energy. At other times, he is an eloquent guide to Guthrie’s writings, many of which had not been previously presented to the public. Kaufman spent a year in the Woody Guthrie archives, poring over manuscripts, song drafts, and unrecorded lyrics in addition to published material. His impressive bibliography contributes to the ample historical context informing Guthrie’s political positions, though occasionally the book reads almost a little too much like a stringing together of Guthrie’s vast output. Kaufman follows Guthrie’s radical development from his youth to his death in 1967, and briefly examines Guthrie’s ambivalent legacy from a radical perspective. Bob Dylan is Guthrie’s best known torchbearer, but Guthrie himself may not have been interested in Dylan’s deeply introspective and obscure approach to political songwriting. “This Land is Your Land” never fails to inspire a certain American sentiment and it has been adapted many times around the world, but contemporary performances all too often omit the verses that best express Guthrie’s radicalism:

As I went walking I saw a sign there

And on the sign it said "No Trespassing."

But on the other side it didn't say nothing,

That side was made for you and me.In the shadow of the steeple I saw my people;

By the relief office I seen my people.

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking,

Is this land made for you and me?Nobody living can ever stop me,

As I go walking that freedom highway

Nobody living can ever make me turn back

This land was made for you and me.

(Guthrie 1956)

Kaufman’s book will be accessible to laymen readers of all stripes as well as scholars from many fields; it speaks to history, radical studies, ethnomusicology, and American studies among others. It stands as the authoritative source on Guthrie’s political life and should also serve as a model for narrating the lives of radical artists. Public voices of dissent and radicalism are needed now as ever; in Woody Guthrie, we have one that will endure.

Video 1: Woody Guthrie: "Two Good Men"

Video 2: Woody Guthrie: "All You Fascists Bound to Lose"

References:

Guthrie, Woody. 2011 [1956]. “This Land is Your Land.” Woody Guthrie Archives. Retrieved 9/28/11. http://www.woodyguthrie.org/Lyrics/This_Land.htm

Kaufman, Will. 2011. Woody Guthrie: American Radical. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Marx, Karl. 1999 [1852]. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Marxists.org. Retrieved 9/28/11. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/

Images:

Figure 1: Uncredited. Bencourtney.com. Retrieved 9/28/11. http://www.bencourtney.com/peekskillriots/

Figure 2: Alexanderson, George. The New York Times. Retrieved 9/28/11. http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2009/09/03/nyregion/20090903-TOWNS_4.html

Figure 3: Balog, Lester. Woody Guthrie Archives. Retrieved 9/28/11. http://www.woodyguthrie.org/biography/biography9.htm