The Forging of Musical Festivity in Baloch Muscat: From Arabian Sea Empire to Gulf Transurbanism to the Pan-Tropical Imaginary

Figure 1. Muscat.

Muscat is known internationally as a low-key, unassuming city with a faint aura of Indian Ocean mystique. Far less ostentatious or fast-paced than other Gulf capitals, Muscat's landscape is dominated by pools of blinding white villas densely collected amid the crags and shadows of a barren, rocky coastline. Owing to the legacy of the late Sultan Qaboos, Oman is one of the most peaceable and staunchly diplomatic nations in the world. Omanis often express pride in their ruler, their culture, and the respectful harmonious nature of Omani society. But also unique to Oman is its history as an empire in the Western Indian Ocean region whose holdings once extended from Zanzibar to the Gwadar peninsula, a history bound up with centuries of the Indian Ocean slave trade. One result of this transregional history today is an explicit acknowlegment of the diversity of Oman's citizenry, with Arabs, WaSwahili (or Zanjibaris), and Baloch the largest of the groups gathered together under a unified - but explicitly pluralistic - national identity.

Muscat bears the commonly overlooked distinction of being a major capital of Baloch culture, and home to the largest concentration of Baloch in the world outside of Balochistan and Karachi. In this article, drawing on my doctoral fieldwork conducted in Muscat and throughout the Gulf from 2014 to 2017, I contend that the contemporary popular music produced and consumed by Muscat's Baloch community refracts into multiple strains inscribed with specific geocultural orientations. No single current of cultural performance can comprehensively encapsulate this diverse community. It is necessary to understand Oman's Baloch communities variably as a long-entrenched part of the cultural landscape of this stretch of the coastal Arabian Peninsula; as possessing a cultural heritage closely linked to the various regions inside and adjacent to Balochistan; as descended from Baloch who represented a highly mobile presence in the greater Western Indian Ocean region; and as operating in close contact—through transnational circuits—with Baloch communities in Karachi, Stockholm, and elsewhere in the Gulf.

Baloch Communities in Oman

Oman and the Gulf coast of the Arabian Peninsula are among the core spaces inhabited by Baloch as a globally distributed collectivity. The proximity of the region to Balochistan, in particular the coastal Makran region, across the narrow Gulf of Oman (or Gulf of Makran) tempts one to think of these peninsular territories as annexes to Balochistan—they certainly function as such given the intensity of Baloch cultural and political activity sustained in these locales.

Centuries of migration from Makran—the portion of Balochistan that straddles the Iran-Pakistan border along the Arabian Sea coast—have created layers of Baloch community distinguishable in part through the extent to which Baloch language remains in use and familial ties to Balochistan are maintained. Recently naturalized and first-generation Omani Baloch citizens tend to be acutely attuned to the ongoing political crisis in Balochistan, constantly consuming news broadcasts in Baloch, Urdu, and English. Baloch have never accepted Iranian or Pakistani rule, as the territory in which they are concentrated is largely treated as a sparsely populated strategic buffer between geopolitical zones and a point of access to the Indian Ocean with little thought as to their local needs for economic development or political autonomy.

Figure 2. Map of Gulf of Oman (or Gulf of Makran).

The armed insurgency has peaked and receded over the years but since 2006 has flared again to a high level of intensity, while the Pakistani military and intelligence services, often with the aid of unspecifiable non-state actors, have been waging a violent campaign against Baloch activists and civilians with the apparent intent of breaking the spirit of this insurgency. One severe point of contention is ongoing Chinese investment in developing the coastal Makrani city of Gwadar into a major industrial port for the onward shipping of natural resources transported across Balochistan through a major pipeline project. The local view of this frenzy of investment and development is that it has completely bypassed Baloch as logical beneficiaries of the resulting revenue and employment opportunities. Ironically, where Baloch are excluded from paths to prosperity on their own turf, they have been consistently enticed by various windows of opportunity to relocate to the facing shores of the Arabian Peninsula.

One basis for significant waves of Baloch migration has been recruitment to Oman's armed services, which at times have been predominantly Baloch in their constitution (Peterson 2007:79). To this day, Baloch are well represented in the military, royal guard, and police force. Baloch are also well represented in the arts, the IT sector, education, and all manner of skilled technical labor and commercial enterprise. Muscat boasts a vast community of Baloch intellectuals actively engaged in literary forums that form part of a transnational network that extends to the other Gulf states and to Balochistan, Karachi, and Scandinavia.

Muscat's Baloch population is concentrated in multiple pockets dispersed throughout the city. Some Muscat Baloch communities are marked by an intensely transnational orientation binding Muscat to Makran and Karachi in heavily trafficked circuits. The more transnational Omani Baloch habitually sponsor fellow Baloch as resident guest workers—as servants, drivers, cooks, maids, nannies, musicians—for short term residencies. This pattern reifies an environment that is culturally, socially, and linguistically Baloch.[1]

Other communities are more confined in their outlook to their local Omani surroundings. Their consciousness of Balochistan is faint even as they hold on to Baloch language, custom, and identity. I will refer to the latter as Mashkatī Baloch,[2] as their spoken Baloch and social comportment have evolved into a localized variety, distinct from the culture of Makran. Recent arrivals are mainly from the eastern (Pakistani) side and speak Baloch with a noticeable Urdu inflection, while the much longer-established communities have come predominantly from the western (Iranian) side and have absorbed much from the local Arabic spoken in Muscat.

Delineations between and within the categories Arab, Swahili, and Baloch in Omani society are complex. A Swahili/Zanjibari identity, for instance, may equally bespeak slave ancestry or a lineage of repatriated Omani Arabs who had relocated to East Africa for generations, absorbing Swahili language and culture in the process even while retaining an Arab identity (al-Rasheed 2013:101). As Majid al-Harthy (2012:102) has found, Omanis in general have resisted confronting, openly and collectively, the history of Indian Ocean slavery and the role of Omanis in it.

Among Omani Baloch, places of origin in Balochistan vary widely, as do the points of entry and nodes integration into Omani society. It is the norm for Omani Baloch to marry Baloch—frequently non-Omani citizens—and for Omani Arabs to marry other Omani Arabs. However, there are many exceptions, such as one Omani Baloch I met who had married a Palestinian from Gaza. The intricacies are virtually endless, but I wish here to emphasize the social and cultural perspectives of Baloch communities. The worldview of these communities is frequently enlarged as though simultaneously sited in Muscat and in nearby Balochistan. For instance, the ideologies of the Baloch Students' Organization and other facets of Baloch struggle against state oppression are frequently espoused in everyday conversation by Muscat-based Baloch, including Omani citizens. These stances explicitly call for social egalitarianism (Dashti 2017:145) and directly challenge the same tendencies toward race-, class-, tribe-, and religion-based ta'assub (chauvinism) that tacitly foster social boundaries in Oman.[3] Baloch communities also operate against a vivid backdrop of transoceanic Omani empire in which they recognize continuous encounters between East Africans, Arabs, Persians, Indians, Europeans, and virtually everybody else.

The Intersection Between Makrani Baloch and East African Cultural Performance and Identity in Muscat

Muscat's past is enshrined in memories of an Omani empire that once extended to Zanzibar, Mombasa, and Kilwa in East Africa and Gwadar in Makran (now part of Pakistan). This was a period of wealth and military prestige but also the peak of the Oman-dominated Indian Ocean slave trade, which was smaller in scale but of longer duration than the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and no less brutal. Baloch traders and commanders were heavily involved in the Oman-dominated slave trade that bound the Arabian Peninsula to East Africa and mainland west and south Asia. For a period, Zanzibar functioned as the Omani capital.

The international abolition of slavery coincided with the height of the Indian Ocean trade in dates and pearls in the early twentieth century. Suddenly, in the Gulf region, East Africa was replaced by Balochistan as a source of labor (Hopper 2015:203–4), as the British navy aggressively patrolled the waters of the Arabian Sea, intercepting dhows bearing slaves from East Africa. Famine in Makran and adjacent coastal regions of South Iran (also largely Baloch populated) forced segments of these populations into slavery (ibid). The prior flows of migration (comprising farmers as well as slaves) from East Africa to Makran and the adjacent portion of southern Iran (Izady 2002:61) meant that many drawn into this early twentieth-century wave of slavery were themselves of at least partial East African heritage even if they arrived in Oman and elsewhere along the Gulf coast of the Arabian Peninsula as linguistically and culturally Baloch.

As Oman's power receded, the Sultanate entered a period of isolation marked by an insular, conservative society through much of the twentieth century until, in the midst of a series of secessionist uprisings, the late Sultan unseated his father and took over, initiating a period of rapid modernization. From the 1930’s until the accession of Sultan Qaboos, severe restraints had been placed on musical and ritual practices that did not conform to the moral vision of the Ibadi doctrine embraced by the ruler and much of the Omani population (Christensen and Castelo-Branco 2009:32–35; Sebiane 2014:58 and 58, n.17).

Today, Oman is resplendent with much-touted regional “arts” (funūn) that at times might be mistaken for music and dance. How the aforementioned restrictions were applied prior to 1970 would have varied. Oman's wide terrain of musical and ritual performance extends from manly dances such as the razhah to expressions of piety such as mālid and the recitation of the barzanjī to practices coded as categorically non-Arab in origin (whether Swahili, Baloch, or Ajam—Persian) to casual, modern—and morally fraught—types of popular entertainment (see Shawqi 1994:152–3, 109–10; 115; 134; 29–30; 183). Among the practices that were targeted by these restrictions was a ritual-festive dance called lēwa that was an emblem of Bantu African origin (Sebiane 2014:58). This dance, today, is understood throughout much of the Gulf as an expression of African heritage, but in Oman, UAE, and Karachi, its primary associations are dual: simultaneously Makrani Baloch and broadly African.

Lēwa is danced in a circle with repetitive figures played on a conical double reed aerophone (Ar. mizmār, Sw. zumari, Pers./Bal. sūrnāī) and rhythm patterns played on a combination of footed and double-headed skin drums and metallic idiophones, all of which have multiple names depending in part on whether Swahili, Baloch, or Arabic terminology is used. The melodic intonation does not recall other Persian, Arab, or Baloch dance melodies of the Gulf region. The layering of the drum and idiophone parts likewise has a distinctively polyrhythmic character, while the repetition of groupings of three beats recalls plenty of other dances of the region. The dance itself involves a group of dancers, sometimes all-male, but in Baloch settings often mixed, who process in a circle, pivoting their bodies to face inwards and outwards. At Baloch weddings in Muscat, the dohol and timbūk (Ar. rahmānī and kāsir, Sw. vumi and chapuo)—a pairing of respective larger and smaller varieties of double-headed skin drum played standing variably with hands and sticks—are a focal point of the dance. The musicians occupy a space in front of the circle formation and the dancers pause and direct their energies expressively towards the double-headed drums for a spell each time they pass closest to them. In lēwa performances that are not explicitly Baloch, the presence of an upright footed drum (sheh faraj, būm, mugurmān)—iconographically evocative of East African culture—is essential.

There has been much hypothesizing about the origins of the lēwa idiom (Sebiane 2007, 2014, 2017; Hopper 2015; Olsen 2002), the extent to which its African origins can be specified, and above all the extent to which its practitioners ought to be ascribed an African, slave-descendent identity. There is a core affinity between lēwa as a complex of ceremonial-festive idioms combining a circle dance with repetitive motifs and rhythm patterns played on the double reed shawm and a variety of drums and idiophones and a variety of similar genres found in the Zanzibar and Lamu archipelagos but in the view of researchers culturally tied to nearby inland regions of East Africa, in particular “the Mijikenda musical and ritual practices of the Mrima region” (Sebiane 2017). Mtoro bin Mwinyi Bakari (1903:159-60) mentions a dance/ceremony called pepo wa lewa among numerous dances that require an mpiga zumari (double-reed flute player) while the msewe dance still performed in Pemba bears a striking similarity—both musically and choreographically—to lēwa performnaces I have observed in person and via documentation (see Video 1).

Video 1. Ngoma ya Msewe

This latter domain of dance is most easily understood as practices of mainland interior cultures transplanted to the Swahili zone, while the prominence of the zumār (a term of Arabic etymology and an instrument organologically nearly identical to the Persian sūrnāi and Egyptian mizmār; see figure 3) certainly recalls sustained contact with Arab, Iranian, or Baloch musical spheres. Being of a notably large stature in comparison with the Persian sūrnāi or the Egyptian mizmār, perhaps the zumari (also called sūrnāi or mizmār in the Gulf) should be considered alongside the usage of the even larger conical double reed shawm known as karanay[4] at Baloch wedding festivities in cities to the west of Jask in coastal Hormozgan, southern Iran. The texts sung combine Arabic and Swahili (and likely other Bantu languages) and are not necessarily well understood by those singing them (or those writing about the genre).

My interpretation of the implicit narrative underlying this complex of idioms is that the East African dances were practices that evolved in response to the Swahili environment as experienced by people from the interior. Lēwa—as practiced in Yemen, Southern Iraq, Southern Iran, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE, Oman, Makran, and Karachi (to be clear on the full scope of its distribution)—further extends this same succession of encounters between communities of East African Bantu background and other cultural groups through onward journeys to settings specific to the coasts of the Arabian Peninsula, Southern Iran, and Balochistan.

Figure 3. Mizmār played during a lēwa performance by Firqat Almas at a celebration of maritime heritage in Kuwait City, 2014

The consistency among certain core characteristics (melodic themes, rhythm patterns, texts, sequences, terminology, dance) attests to the degree of sustained connectivity between these coastal regions. As Majid al-Harthy (2010:226) and Maho Sebiane (2014:63) spell out clearly, names of spirits that consistently figure into spirit possession ceremonies practiced in the Arabian Sea/Persian Gulf region (of which lēwa in certain instances is one variety) explicitly point to interior regions of East Africa and their populations.

In the early twentieth century, slaves in Oman found a portal to freedom through the influence and presence of the British and French, who—despite centuries as the most egregious proponents and enforcers of chattel slavery on a global scale—were obliged to observe the International Slave Trade Convention. This was a proclamation that assured freedom to whoever sought “refuge under the flags of the Signatory Powers, whether ashore or afloat” (Cox 1925:196). According to Percy Cox, former slaves were often found engaged in music-making in the form of different kinds of fanfare played on occasions commemorating the British sovereign (ibid.). Are we to infer from Cox's account that the British had proved worthy of musical adulation as a force of antislavery? Or should we consider the use of tributes to the powerful British empire to frame festive practices that bore deeper meanings and functions and historical narratives as a means of insulating these practices from administrative forces that would otherwise suppress and denounce them?

The ceremonies known as zār, in which men and women who have been identified as inhabited by a spirit are treated through ritual means, generally incorporating drumming, chanting, dance, and at times instruments such as a baritone lyre (tanbūra, tanbīra), have often been met with scorn and have occasionally been outlawed.[5] We know from Kaptijn and Spaulding (1994:10–19) that practitioners of ceremonies with a clear African association,[6] such as zār,[7] have had to strategize carefully from multiple angles in peninsular settings to be allowed to uphold these ceremonies that have long been viewed as being incommensurate with both Muslim piety and colonial European civilizing projects aimed in particular at Africans.

As Lindsey Doulton, discussing manifestations of gratitude shown the British navy and the Crown (Queen Victoria) by freed African slaves settled in the Seychelles, observes, “antislavery, however, no longer constituted merely an opposition to slavery; it was about ending slavery and planting what British officials called civilization in its place” (2013:102–3). Many of the available sources Doulton cites that reinforce the sense of gratitude expressed by freed slaves are autobiographical accounts by former slaves who had converted to Christianity, suggesting that it is mainly among slave-descended Muslim citizens of Arabian Sea/Persian Gulf nations that practices like lēwa and zār continue to be practiced.

The incorporation of venerated Muslim figures—Abdelqadir Jilani, Ahmed Rifa'i, Ahmed al-Bedawi, Aydarus, Farid ud-Din Ganjishekar, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, Hazrat Bilal, and the Prophet and his descendants—into ritual frameworks related to zār might on some level represent concessions to Islam as a confessional orientation imposed from above. But of more immediate consequence to the present moment, we should consider practices such as zār and lēwa as (a) being constantly evolved in response to shifts in circumstance and environment, (b) being inherently open to incorporating the powerful ideas about spiritual force represented by Abdelqadir Jilani, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, and other mashāyekh[8] of regional stature, and (c) possessing such value as expressive—ultimately unifying—spaces for communities that any strategic tailoring to the idiosyncrasies and constraints of a given environment would itself have been enacted in a spirit of reverence.

The extent to which Baloch retain a very clear sense of cultural distinction while also displaying enthusiasm for participating in the embodied worldviews of their neighbors and others with whom they have sustained contact is striking. Lēwa and dammāl—a vigorous devotional drumming and dance complex most acutely associated with the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalander in Sindh—are prime examples of ostensibly exogenous spheres of ceremonial performance that have become defining currents within segments of Makrani and Mashkatī Baloch society. In Karachi, and among Baloch transplated from Karachi to Muscat, the idioms of dammāl and lēwa often converge in festive contexts.

Baloch Musicians in Oman at the Threshold of Modernization

Because of the jumble of different practices and their cultural frames of reference and efforts from various quarters to suppress them, boundaries have become blurred between possession ritual, communal festivity, and Muslim observance. Baloch, culturally, have never had a reason to deny the musicality of their music (for which the generic Baloch term is sāz). I am unable at present to comment on the extent to which motions to discourage or suppress musical practices under Sultan Qaboo's father (Sa'id bin Taimur) impacted the wedding dances of Baloch in Batinah called daqqa Balūshiyya in Arabic and tamāsha in Baloch, which are still widely performed.

One Baloch informant in Muscat reported to me that his household looked mainly to zār and lēwa as their spheres of engagement as performers prior to the 1970s. In the early 1970s, he himself went to Karachi and bought a benjū[9] from the famous Makrani Baloch benjū maker and musician Joma Surizehi and became a wedding musician in Muscat. During this period, new strains of Mashkatī Baloch popular music were freely improvised, looking to all directions for inspiration. Musical wedding entertainment among Baloch, then concentrated in the historic port town center—Old Muscat, Matrah, Jibroo, and Sidab—combined popular Arab genres, contemporary urban Baloch trends, lēwa, vigorous dammāl-style drumming, and comedy and dance routines.

Musical Sojourns from Makran

Omani Baloch whose fathers were recruited during the conflicts from 1952 to 1975 and subsequently granted citizenship represent a relatively affluent segment of Muscat's Baloch population and have maintained social, cultural, and ideological ties with their homeland. This contingent represents a vital portion of the patron class who actively support Makrani Baloch singers and musicians, who are typically poor, low caste, hereditary musicians, in some cases affixed as clients to a specific tribal lineage.

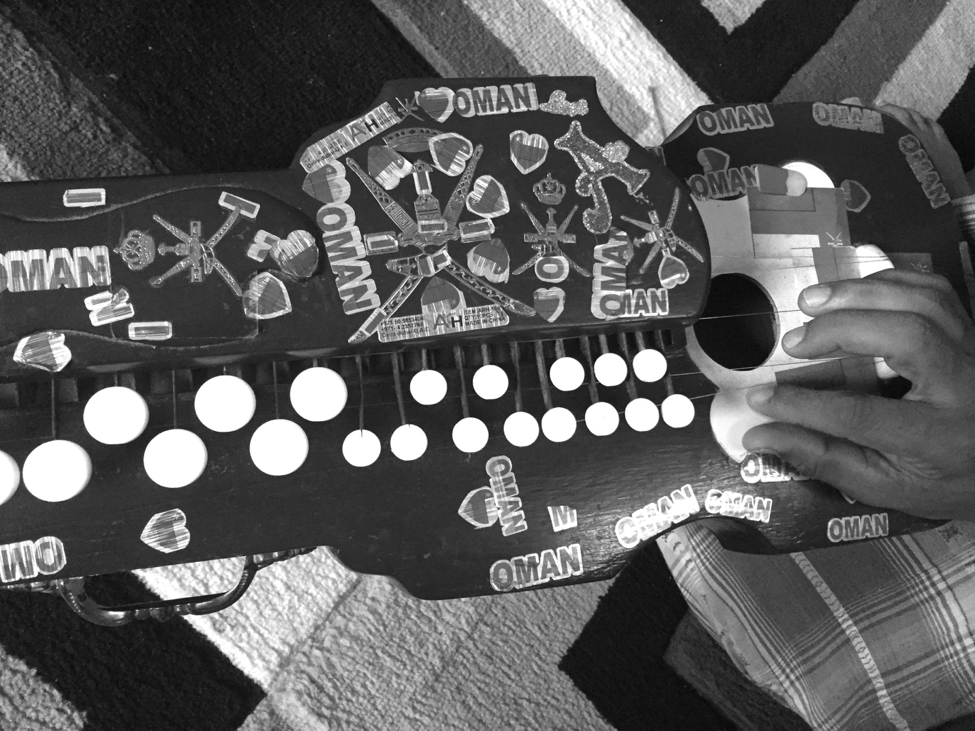

Figure 4. Benjū belonging to a retired soldier—a Dhofar war veteran—and Omani Baloch citizen.

In Makran, most professional instrumentalists and singers belong to a group known as lodi or domb, terms which connote hereditary artisans of non-Baloch origin who have assimilated to Baloch culture and language (Badalkhan 2000:781). They sing the poems composed by their wealthy patrons, perform famous epic poems at occasions of import, entertain both men and women (usually separately) at weddings, and provide music for spirit possession rituals, to list some of their primary vocational activities.

Today, wedding entertainment provided by such musicians represents a modern, urban current of music informed by Baloch politics and social concerns and by music and poetry styles associated with the Urdu ghazal as well as other strains of widely circulated South Asian popular music.

Wedding in Muscat featuring contemporary musicians from Makran

The process of patronage extends beyond supporting performers by sponsoring their visas, covering travel, housing them, and hiring them for performances. Baloch of means play a significant role in launching the careers of popular singers through creating a buzz around those they favor and paying for their studio recordings, which always wind up circulating so freely that the return for the investment of covering their production costs comes in fame for the artist rather than revenue from sales. To have such recordings widely listened to naturally means that the lyrical content—invariably the words of a contemporary Baloch poet, often the patron—also receives significant exposure.

Sponsoring and supporting musicians is also a gesture of magnanimity towards ones community, creating otherwise nonexistent spaces for cultural performances to be ennacted and experienced. There are different ways that audience members engage with musical performances, and varying degrees to which this engagement becomes externalized. A prominent subset of young men in Muscat is intensely drawn to expressive dancing (Bal./Urdu natch) at live musical performances. The majority of attendees exercise a certain amount of socially ingrained reserve and will not allow themselves to spontaneously erupt into prolonged fits of dancing. Those who have forsaken this code of reserve need very little prompting to get into the swing.

Dancing at wedding in Wadi Hattat, Muscat

The Lyari Connection

Lyari is a large, old town[10] district of Karachi with a reputation as a place of poverty, overcrowding, criminal activity, and social tensions. Lyari is also renowned for its cultural life, especially in the domains of music and sports (Paracha 2018:72). Lyari has long been a center of urban migration for Makrani Baloch—many from the Iranian side of the border, and this has helped build up Karachi from a small coastal fishing town to Pakistan's largest city (Slimbach 1996:139). A significant population of Lyari also identifies—or is identified—as possessing African heritage, giving rise to the use of terms such as Shidi, Afro-Baloch, and Afro-Sindhi, and locally imbuing the term Makrani with racial and class connotations (Paracha 70-71).[11] Lyari has its own Baloch and Urdu accents, its own pop and hip hop scenes, and boasts numerous football and boxing stars alongside notorious gangs and gangsters (ibid 72).

Khodabaksh Mewal is a long-time resident of Matrah who was part of the coterie of wedding performers who served as the vanguard of modern Baloch music that emerged in Muscat in the 1970s and 80s. He has retained close ties to Lyari through family connections and frequent visits. Today, he leads an ensemble featuring his own grown sons. Their sound might seem dated alongside other Muscat Baloch wedding bands, but it continues to be informed by new streams of music produced in Lyari, where a tinny, monophonic, slightly harsh keyboard timbre is integral to a prevalent musical aesthetic. A centerpiece of wedding performances is a festive lēwa dance that aligns both with Baloch lēwa as reimagined in Lyari recording studios and with the specters of old Muscat, where lēwa was a ritual expression of the transoceanic perambulations of human and spirit cultures.

Here is an open air lēwa performance in Lyari (Video 2), where costume and body paint worn by dancers, after the fashion encouraged by the Indian government among Sidi performing troupes in India (Meier 2004:90), overtly caraciturize African heritage in the spectacle:

Video 2. Open air lēwa in Lyari

A pop rendition of lēwa that is equally popular in Karachi and Muscat and often musically reproduced at weddings continues to uphold this same strain of exoticist pangeantry:

Video 3. Baloch pop lēwa video

Aspects of Khodabaksh Mewal's band's repertoire that directly point to Karachi include the feminized male dancers known as jenīnū and the distinctive keyboard sounds that are subtly abrasive and reverb-laden in some cases and in others clearly serve as a stand-in for the sound of an amplified benjū. It is important to bear in mind that it was in Karachi that the benjū was first absorbed into Baloch musical spheres.

Khodabaksh Mewal's band perform lēwa at wedding in Jibroo, Muscat

Khodabaksh Mewal's band perform at a wedding in Muscat

A Local Mashkatī Cosmopolitanism

Baloch acquaintances have often asserted to me that, despite a deep loyalty to Baloch culture and values, one unique quality that Baloch collectively possess is an extraordinary adaptability. Indeed, it is hard to think of another group in Muscat that is as at ease in their interactions with all the other fairly rigidly delineated contingents—South Asian guest laborers, the highly paid British and American white-collar ex-pat workforce, Omani Arabs and Zanjibaris—as Omani Baloch. Baloch are well represented in spheres of music-making as diverse as the Oud Hobbyists' Association, the Royal Oman Symphony Orchestra, and the top 40 cover bands that play New Year’s Eve parties and similar engagements at Muscat's luxury hotels.

If these contexts can easily be understood as catering to largely non-Baloch audiences, within Baloch circles one finds an embrace of certain globally circulating popular culture flows. This spirit is embodied above all in the legendary and now long disbanded group Los Balochos, who drew on the hits of the Gypsy Kings and various Latin America- and Iberia-themed aesthetic conventions, and who continue to inspire young Baloch musicians long after their dispersal.[12] I encountered one group of Los Balochos disciples who consisted of multiple acoustic guitars, tambourines, singers and clappers, and a virtuoso cajòn player who also played drums in a big wedding band. While songs emulating the Gypsy Kings formed the backbone of their repertoire, at an informal, convivial gathering I attended with them, they also veered into a rendition of Pakistani folk singer[13] Reshma's famous arrangement of the Qalandari chant Dama Dam Mast Qalandar and a succession of Baloch revolutionary songs.

Baloch band informally covering the Gypsy Kings

By far the most vibrant strain of Mashkatī Baloch musical culture is the proliferation of youth-driven wedding bands. These are large ensembles combining electric and electronic instruments (guitar, bass, keyboards) with large percussion sections that reveal the scope of currents intersecting in the unique fusion these bands have come to represent—dholak, tabla, rock drum kit, cow bells, roto toms, congas, double headed drums, and frame drums (tārāt).

The phenomenon of large, eclectic ensembles-for-hire combining local and global musical orientations is extremely commonplace virtually across the globe, whether we think of a modern Tachelhit band performing for migrant Ishelhīn in Casablanca or a state of the art orkes gambus in Jakarta. Nevertheless, a number of factors vividly differentiate the Mashkatī Baloch wedding band.

Songs are long and episodic, usually about 20 minutes long and largely revolve around responsorial chants and relentless drum-based grooves. Within these streams of live performance, a wide range of genres and stylistic vernaculars collide, recalling and at times reproducing contemporary Gulf Arab bands such as Miami Band, Iranian pop staples, Bollywood hits, Pink Floyd covers, and Makrani- and Lyari-style Baloch songs.

There is a lively scene surrounding these large, youth-driven, Baloch wedding bands in Muscat, with perhaps a dozen or so reigning at any given moment. Some of the most popular include al-Muna, Nawras, Ayla, and Mayasim. Singers such as Ali Alash and Nadim Shanan work with these bands but cultivate their own names through social media self-promotion and studio recordings. Within densely percussive extended dance sequences that are central to this repertoire, vocalists often lead chants and exhort the musicians and attendees to new heights of excitement (see Video 4).

Video 4. Nawras band with male youth audience

At the rare formal occasions that intersect with the greater Omani public sphere, such as a performance given by the Muna band at the inauguration of a new shopping mall in Muscat in 2019, it is almost jarring to see these groups adorned in pristine Omani national dress, although virtually all performers of music and related arts showcased at national festivals wear the characteristic white gown and turban on those occasions. The uniform for bands and male attendees at a open air wedding parties is street fashion, more along the lines of factory shredded denim, athletic gear, and tight-fitting, pastel-colored, t-shirts and pants. Apart from the group dynamic that drives these large ensembles, singers cultivate idiosyncratic, often highly emotive personas, chiefly foregrounded in the introductions to the extended dance-oriented sequences and in interludes between them.

Nadim Shanan and Nawras band at a wedding in Muscat

The singer featured in the above excerpt is Nadim Shanan, performing with the Nawras band. His late father, known simply as Shanan, was a very well known Mashkatī Baloch singer who projected a comic aura in his recordings and performances, especially through the use of wordplay and nonsequitous utterances. Some of his songs offer a unique portrait of street life in Baloch neighborhoods such as Khoudh, describing in one case characters whose guts have been eroded by habitual abuse of a common household cleaning product.[14] It is worth noting that Khoudh is the site of extensive social housing chiefly constructed for Baloch who had to be relocated to various outlying parts of Muscat when the walled Baloch quarter of Jibroo—one of the most densely populated sections of old Muscat—was carved up and partially razed to open up a centralized space for government buildings (Bream and Selle 2008:17).

The transition to a modern, post maritime Gulf cosmopolitanism is whimsically present in one of Shanan's studio-recorded songs, which bears the refrain se bai dihem ya se bai dihem, invoking a greeting in Thai. To a sing-song melody he sets the following lyrics:

Fī Arabi yagulu, “Kēf halak?”

Fī Baloch yagulu “Chī tōr ē?”

Hindī yagūlū, “kaisa hai?”

Fī Inglizī, “Hi how are you?”

Fī Swahīlī, “Jambo jet.”

Fī Thailandī, “Ka pom ka.”

Fī Somālī, “Kandā kap”

Wa al-bāqī, “eeyeeyeeyeeyee”

[In Arabic they say, “Kēf halak?”

In Baloch they say “Chī tōr ē?”

In Hindi they say, “kaisa hai?”

In English, “Hi how are you?”

In Swahili, “Jambo jet.”

In Thailandi, “Ka pom ka.”

In Somali, “Kandā kap”

and the rest say, “eeyeeyeeyeeyee”]

Each of these is more or less a legitimate greeting in the specified language with certain exceptions. In Swahili, he adds “jet” to the common greeting jambo thereby approximating “jumbo jet” —indeed these greetings are of the general register of things flight attendants say to welcome passengers on board and to assure them that there is a cultural link between the in-flight environment and the airline's national association (if not the actual destination). And by substituting for any actual Somali greeting a Baloch phrase meaning, “go fall in a hole,” he suggests for comedic effect a lack of knowledge of Somali (despite the fact that Shanan at the time I met him included Somali among the languages he worked with as a professional court translator, having retired from his career as a police officer). The other component of the song's text is a familiar song children sing on a night midway through Ramadan as they go collecting sweets, a tradition known locally in Muscat and Batinah as qaranqaşo. The song, in Arabic, varies from country to country and he sings a local version:

Qaranqaşo yo nās, 'atīnī shwāya l'halwa,

Dūs, dūs, fī'l-mendūs, Hārah hārah fistik hārah

“qaranqaşo”[15] people, would you give me some sweets...

toss them into the box, neighborhood to neighborhood, pistachio-neighborhood![16]

The song was devised around this children's rhyme, according to Shanan, who explains that someone had recognized him at a hotel in Delhi and knocked on his door holding a box of sweets, prompting Shanan to recall that Ramadan tradition in the context of an encounter between two Muscat Baloch strangers in India.

Audio example 1

Another well-known singer whose stature extends to earlier periods is Hosein Sapar, who led a popular Baloch wedding band in the 1980s and then withdrew, impelled by religiosity to give up music completely. Renowned for the syrupy, almost over-the-top sweetness of his voice, he has recently re-emerged, not as a professional singer but as a guest performer at weddings and on recordings. Here he sings an impromptu ditty from his seat to the side of a wedding hall, while a keyboard player on stage accompanies him. After he finished he proclaimed, “salonka wasta” (“for the groom”).

Hosein Sapar at a wedding in Muscat

The sound of the current wave of Baloch bands is meant to appeal directly to two specific social spheres whose separation is often guaranteed by a moral conservatism that pervades old Muscat Baloch communities—women in intimate seclusion and young men in eager aggregation. While these bands play at a range of wedding-related festivities, the rationale behind creating such an elaborate tapestry of dance music is really the desire of women to dance together at segregated female segments of wedding celebrations, such as henna parties (Baloch, henna bandān). In this audio example, recorded at a women's henna party in the Wadi Hattat section of Muscat, where video recording was out of the question, an upbeat, generically tropical dance tune, bearing no melodic relationship to any strain of Baloch folk music, is intertwined with contemporary interpretations of lēwa motifs that are asserted in passing before the song reverts to its upbeat pop textures:

Audio example 2

In intimate community settings, even in public environments such as an open-air gathering on a residential street, this segregation is more spatially expressed than fully realized. In such cases—and at mixed or all-male celebrations—young men, the second camp alluded to above, crowd in to listen to the band, whose style and sonic aesthetic is a focal point for their own sense of cultural belonging as young Baloch men who identify with specific neighborhoods in Muscat, especially Jibroo, Khoudh, Maabila, and Wadi Hattat. The overlap in material, setting, and social context between these bands and Khodabaksh Mewal's group is considerable. Only, Khodabaksh Mewal's group is closely linked in repertoire and aesthetic both to Lyari and Old Muscat while these bands cultivate a brand new, unmistakably Muscat Baloch sound that holds a magnetic draw for young men and teenagers in search of environments for sociality and personal expression. Here al-Muna band sustains a repetitive chant and groove, building to a characteristic dynamic swell:

Mona Band at a wedding in Muscat

Circles of music-making among Baloch in Muscat in 2014-2019 do not invite obvious parallels to other urban contexts, despite patterns common to many other milieus —the cultivation of “hybrid” genres, familiar strains of an acoustic sonic patrimony reimagined through electrified, often electronically enhanced arrangements, and above all, the intersection of “traditional” idioms with more commercial, globally disseminated styles of popular music. Big wedding bands of Baloch Muscat stand in proximity to circles of poets and intellectuals overtly concerned with the fate of a society amid obstructions in access to self-expression and self-knowledge, but ideological interchange between the literary and popular music wings of this artistic environment is rarely overt.

Muscat seeks to brand itself as a tourist destination and to reward its resident white-collar expatriate workforce with creature comforts and intimations of an Indian Ocean tropical paradise. Waterfront five-star hotels, yacht-filled marinas, and palm trees evoke a luxurious foreground to picturesque vistas dominated by dramatic mountain ridges, a rolling, blinding white cityscape, and the sea itself. The musical answer to these ideations is an indistinct pan-tropical mélange recalling in turns a Disneyfied soca, Bollywood ballads, Tehrangeles sentimentality, reggae, rock, and Afro-Latin jazz. This repurposing of the innocuous pop-culture flows coursing through the viaducts of an air-conditioned mall culture also reflects back to the movement from Balochistan to a wider world of Oman and East Africa and the acquisition of a deterritorialized worldliness, an oddly valuable commodity in Muscat and the Gulf more broadly as far as social capital is concerned.

Conclusion

Muscat's Baloch population, with its many-chambered historical and geographic consciousness, is simply too varied to find representation in a unified current of contemporary music practice, even within neatly circumscribed contexts such as wedding celebrations. Interminglings between Baloch communities settled in Muscat's historic neighborhoods and expanding urban sprawl contribute to complex patternings. There is Lyari in Jibroo and Makran in Maabila. Khoudh has been narrated by Shanan, its backstreet mītags[17] sonically embroidered with lēwa and dammāl, sounds that—like bukhūr[18] at a fairground—sometimes billow forth dramatically, a sudden presence but never unexpected.

References

Abbas, Shemeem Burney. 2002. The Female Voice in Sufi Ritual: Devotional Practices of Pakistan and India. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Aksoy, Ozan. 2018. “Kurdish Popular Music in Turkey.” In Made in Turkey: Studies in Popular Music, edited by Ali C. Gedik. London: Routledge: 149–166.

al-Harthy, Majid. 2010. “Performing History, Creating Tradition: The Making of Afro-Omani Musics in Umm Ligrumten, Sur Li’fiyyah.” Ph.D. Diss., University of Indiana, Bloomington.

———. 2012. “African Identities, Afro-Omani Music, and the Official Construction of a Musical Past.” The World of Music 1/2: 97–129.

al-Rasheed, Madawi. 2013. “Transnational Connections and National Identities: Zanzibari Omanis in Muscat.” In Monarchies and Nations: Globalisation and Identity in the Arab States of the Gulf, edited by Paul Dresch and James P. Piscatori, 96–113. London: I.B. Tauris.

ash-Shidi, Jum'a Khamis. 2008. Anmat al-Ma'athur al-Musiqi al-'Omani: Darasat Tawthiqiyyah Wasfiyyah. Muscat: Markez 'Oman lil-Musiqa at-Taqlidiyya.

Badalkhan, Sabir. 2000. “Balochistan” in The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent. New York: Garland Publishing.

––––––. 2008. “On the Presence of African Musical Culture in Coastal Baluchistan.” In Journeys and Dwellings: Indian Ocean Themes in South Asia, edited by Helene Basu, 276–287. Hyderabad: Orient Longman.

Bakari, Mtoro bin Mwinyi. 1903. Desturi Za Wasua-heli Na Khabari Za Desturi Za Sheri'a Za Wasua-heli. Gottingen: Vandenhoed & Ruprecht.

Battain, Tiziana. 1995. “Osservazioni Sul Rito Zār di Possessione Degli Spiriti in Yemen.” Quaderni di Studi Arabi 13: 117–130.

Boddy, Janice. 1989. Wombs and Alien Spirits: Women, Men and the Zār Cult in Northern Sudan. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Bream, Allison and Samira Selle. 2008. “An Assessment of Housing Decisions among Shabia Residents.” SIT Oman. Independent Study Project.

Christensen, Dieter and Salwa el-Shawan Castelo-Branco. 2009. Traditional Arts in Southern Arabia Music and Society in Sohar, Sultanate of Oman. Berlin: Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung.

Cox, Percy. 1925. “Some Excursions in Oman.” The Geographic Journal 66(3): 193–221.

Dashti, Naseer. 2017. The Baloch Conflict in Iran and Pakistan: Aspects of a National Liberation Struggle. Trafford.

Doulton, Lindsey. 2013. “'The Flag That Sets Us Free': Antislavery, Africans, and the Royal Navy in the Western Indian Ocean.” In Indian Ocean Slavery in the Age of Abolition, edited by Robert Harms, Bernard K. Freamon, and David W. Blight, 101–119. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Drieskens, Barbara. 2008. Living With Djinns: Understanding and Dealing with the Invisible in Cairo. London: Saqi Books.

Gharasu, Maryam. 2008. “Mūsighi, Khalseh, va Darmān: Nemūneh-i morāsem zār dar suvāhel-e jonūb-e Irān.” Mahoor Music Quarterly 10/40: 115–138.

Hopper, Matthew S. 2015. Slaves of One Master: Globalization and Slavery in Arabia in the Age of Empire. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Izady, M.R. 2002. “The Gulf's Ethnic Diversity: An Evolutionary History.” In Security in the Persian Gulf: Origins, Obstacles, and the Search for Consensus, edited by Lawrence G. Potter and Gary G. Sick. Palgrave.

Kapteijns, Lidwein and Jay Spaulding. 1994. “Women of the Zar and Middle Class Sensibilities in Colonial Aden, 1923-1932.” Sudanica Africa 5: 7–38.

Khalifa, Aisha Bilkhair. 2006. “Spirit Possession and its practices in Dubai.” Musiké 1/2: 43–64.

Meier, Prita Sandy. 2004. “Per/forming African Identity: Sidi Communities in the Transnational Moment.” In Sidis and Scholars: Essays on African Indians, edited by Edward A. Alpers and Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy, 86–99. Dehli: Rainbow Publishers.

Natvig, Richard Johann. 1987. “Oromos, Slaves, and the Zar Spirits: A Contribution to the History of the Zar Cult.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 20(4): 669–689.

Paracha, Nadeem F. 2018. Points of Entry: Encounters at the Origin-Sites of Pakistan. Chennai: Tranquebar.

Peterson, J.E. 2007. Historical Muscat: An Illustrated Guide and Gazetteer. Leiden: Brill.

Rovsing Olsen, Poul. 2002. Music of Bahrain. Aarhus University Press

Sebiane, Maho M. 2007. “Le statut socio-économique de la pratique musicale aux Émirats arabes unis: la tradition du leiwah à Dubai.” Chroniques Yéménites 14: 117–135.

———. 2014. “Entre l'Afrique et l'Arabie: les esprits de possession sawahili et leurs frontières.” Journal des africanistes 84(2): 48–79.

———. 2017. “Beyond the Leiwah of Eastern Arabia: Structure of a Possession Rite in the LongueDdurrée.” Música em Comtexto Ano XI, vol. 1: 13–43.

Shawqi, Yusuf. 1994. Dictionary of Traditional Music in Oman. Wilhelmshaven: Florien Noetzel Verlag.

Slimbach, Richard. 1996. “Ethnic Binds and Pedagogies of Resistance: Baloch Nationalism and Educational Innovation in Karachi.” In Marginality and Modernity: Ethnicity and Change in Post-Colonial Balochistan, edited by Paul Titus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tiilikainen, Marja. 2010. “Somali Saar in the Era of Social and Religious Change.” In Huskinson, Lucy and Bettina E. Schmidt, Eds. Spirit Possession and Trance: New Interdisciplinary Perspectives. 117–133.

[1] It is not uncommon for Omani Baloch households to employ servants who are not Baloch, but come rather from Ethiopia or Indonesia for instance.

[2] Muscat is rendered as Mashkat in Baloch.

[3] I cannot include gender in this formulation without extensive qualification.

[4] The karanāi often consists of a sūrnāi with a large extension enlarging it and deepening its sound.

[5] There is an enormous body of anthropological and ethnographic literature concerned with zār ceremonies as cultivated across a vast geography centered around the Red Sea, Arabian Sea, and Persian Gulf regions. As a selective set of readings, one finds descriptions of zār in community contexts in northern Sudan, see Boddy (1994); in Southern Iran see Gharasou (2008); in Yemen see Battain (1995); in Dubai see Khalifa (2006); in Cairo see Dreiskens (2008); and within transnational Somali communities see Tiilikainen (2101). For a historical perspective focused on the Horn of Africa, see Natvig (1987).

[6] The use of “African” as a catchall is difficult to avoid when speaking of practices that weave together elements that can be understood as being of cultural origins—Somali, Amhara, Oromo, Nyasa, Yao...—as diverse and difficult to specify as the communities of practitioners, which ultimately expanded to include peninsular Arabs, Baloch, and Persians.

[7] Among Baloch in Makran and Oman, zār is less likely to be practiced than rituals such as guātī, dammāl, and mālid that combine aspects of zār with Baloch, Sindhi, and Arab ceremonial and instrumental/vocal performance.

[8] Venerated masters in the context of Sufism.

[9] A strummed zither fretted using keys that resemble typewriter keys.

[10] Old within the historical time frame of Karachi, which isn't a very old city at all.

[11] A Karachi-born acquaintance of neither African nor Baloch heritage once told me that, growing up, his family finances took a downward turn and suddenly he was no longer welcomed into his customary circle of kids who'd play football with in the afternoons and thus he turned to a lower class location and cohort to play, becoming “Makrani” in the process.

[12] For discussion of a parallel iteration of the global appeal of this musical flavoring, see Aksoy (2018:154).

[13] Reshma is widely considered a Pakistani folk singer in Pakistan, but she migrated to Sindh with her family—who represent a hereditary musicians' caste—from Rajastan and cultivated her singing practice through engagement with devotional idioms at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalander in Sehwan, Sindh (Abbas 2002: 25-30).

[14] Inhaling fumes from glue and various chemical agents is a globally widespread form of substance use, but is not generally openly acknowledged in Oman, UAE, or the other peninsular Gulf states, while in the other countries surrounding the Gulf—Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan—the presence of street drugs and patterns of addiction, crime, and social malaise are much more conspicuous.

[15] Qaranqashu is an onomatopoeia approximating the sound of seashells being clapped together by the children noisily making their rounds. [ash-Shidi 2008 222]

[16] In the absence of direct input from Shanan, who has recently passed away, I have discussed this last line, which is slightly ambiguous, with another Mashkatī Baloch musician who confidently heard it as “hara hara fistik hara” as indicated. What I hear is “hara hara fi as-Sahara,” which would be a play on hara meaning “neighborhood” and har (feminine form: harah) meaning “hot,” and then “in the Sahara” which would have very little logical import but would be entirely consistent with Shanan's charactieristic free associative word play.

[17] A communally cohesive Baloch residential space such as a village or neighborhood, not unlike the Indonesian kampung.

[18] Incense widely used in Oman, especially in ritual settings. Known in Baloch as suchkī.