Delineations of the Invisible: Notes on Max Neuhaus’ Drawing Practice

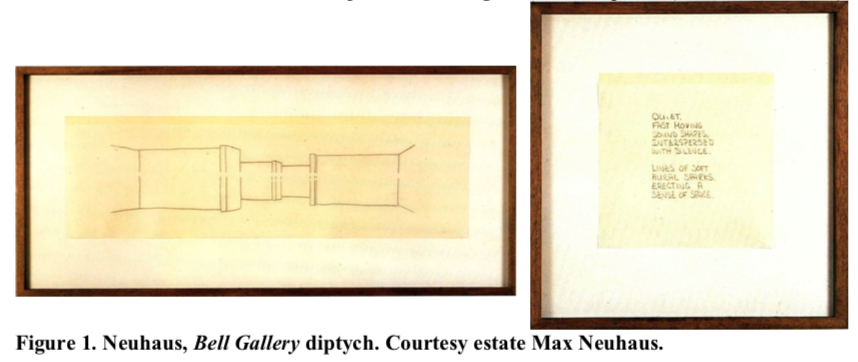

Straight lines are arranged on a page in landscape format, marking themselves out from each other at their junction point: vertical and horizontal lines, some obliques. They're organized according to a perspective that, while approximate, is sufficient for the spatial illusion of a series of open rooms to operate. Because of this approximation however, we can also see the industrial drawing of a cylindrically shaped spare part from an unknown mechanism, a cog in an apparatus. The pencil line is slightly febrile, showing execution by hand, not with a ruler, in spite of the technical aspect of the work overall. Each vertical line is segmented a little above its center by one or, for some, two blank spaces, perhaps erased after the line was drwan, the emptiness tracing just so many horizontal lines that run, invisible, across the entire width of the page. Arranged to the right of the drawing, a second frame, square this time, contains a page on which a few handwritten lines have been inscribed in capital letters, like a poem: "Quiet / fast moving / sound shapes, / interspersed / with silence. / Lines of soft / aural sparks, / erecting a / sense of space" (Neuhaus 1995:59).

This diptych produced by Max Neuhaus in 1993 refers back to a sound installation presented by the artist at the David Winton Bell Gallery in 1983 (Figure 1).[2] According to the precept that guides his work, the starting point for this installation is to be found in the space itself: “the sound which already exists there, the nature of its acoustic and its social context” (Neuhaus 1989:236). The installation here consisted of a set of sixteen speakers connected to a computer system and placed around the exhibition space, invisible to the eye, disguised as electrical equipment around the edge of the ceiling. Each loudspeaker was located in reference to an angle of the room so as to emit an intermittent electronic pulse, a dry clicking sound,[3] towards the angle to give the impression that the sound was coming from the “corners themselves, with their complex patterns of reflection and acoustic shadows” (ibid.). This series of clicks produced an effect of movement, like a phrasing circulating in space. Writing about the work, Neuhaus stated: “When people spoke, it couldn't be heard; but when people were silent, the ear could see this something crossing the room. It constructed its space by articulating it. It exhibited it by moving through it” (1995:115).

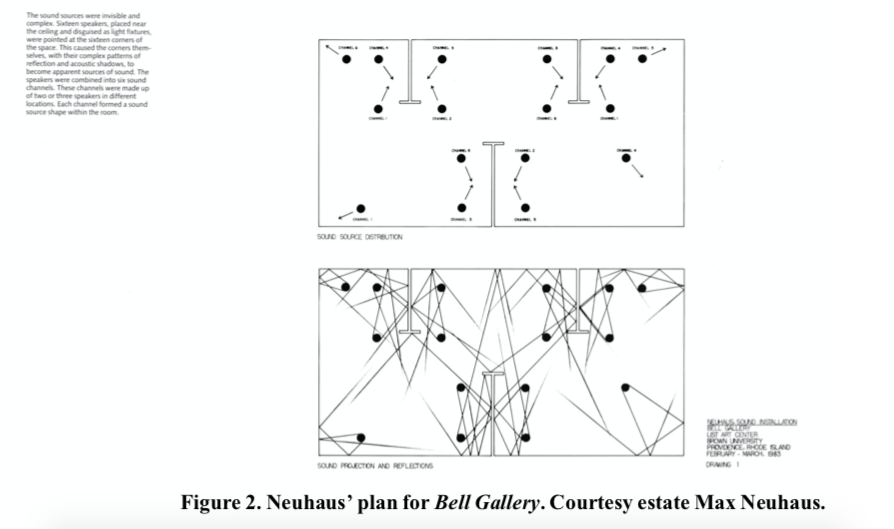

This drawing is not the only imagery documenting this installation. Other drawings, prior to the diptych and this time resolutely technical, show, for example, the plan of the locations and orientations of the loudspeakers, establish an analysis of the reflections produced by each sound projection or provide a breakdown of the sequencing (the turning on and off) of the different sources to highlight the illusion of the perceived journey (these drawings are notably published in Neuhaus [1989:237, 245]). These other drawings indicate directions, trace vectors, and, by adopting a two-dimensional representation, portray propagations in a space consisting here of the acoustic relationships between a sound emission and a site (Figure 2).

Whether of a technical or allusive nature, the drawings that Neuhaus creates for each installation all attest, according to their own modalities, to a situation functioning as an apparatus - both constituted by the installation itself and that defined by the site housing it and the relationships the installation establishes there. In doing so, they probe the experience created: “The listener entering the Bell Gallery was confronted with an empty space – he began to find his place when he noticed the sound” (Neuhaus 1989:244, my emphasis).

Typology of drawings

Before detailing the reports of the apparatuses inscribed in these drawings and how they give us a broader idea of what is going on in the artist's sound installations, it is worth briefly considering their status in Max Neuhaus’ body of work. As we have seen, these drawings fall into different categories, explicitly inventoried as such by the artist. A first set consists of the project drawings, produced while the work was still in the design phase and therefore prior to the installation itself. These are studies created for sponsors and institutions issuing authorizations and budgets necessary for the production of works that were often large in scale and/or that occupied public spaces. The work to be created being fundamentally in situ and sound being only the means and not the end, Max Neuhaus refused to present his projects by means of sound samples, favoring rather a medium conducive to a problematization that would not misrepresent them: “Rather than the vehicle for reducing a three dimensional reality to two, the drawing here can become a means of stating an idea in an open medium, without the fixative of verbal language, a medium outside that of the sound work which does not impinge on it” (Neuhaus 1994b:9).

A second category brings together the technical drawings often undertaken after the installation had been set up, like those mentioned above for the installation at the Bell Gallery. These are working drawings, aimed at illustrating the acoustic properties of a space on paper; they map the phenomena that are deployed in the space. They constitute a sort of explanation for Neuhaus himself, helping to clarify the functioning of complex psychoacoustic relationships, such as the network of reflections generated by the multiplicity of the sound sources mobilized and their effects on perception: “A few weeks after finishing a work, I execute a few drawings to explain what I have produced to myself” (Neuhaus 1992:150).[4] In his interviews, lectures and writings on his drawings, Neuhaus repeatedly insists that these first two categories are radically different from the work, in the sense that “they are not part of the process of perceiving a sound work; they are reflections upon it”(Neuhaus 1994b:11).

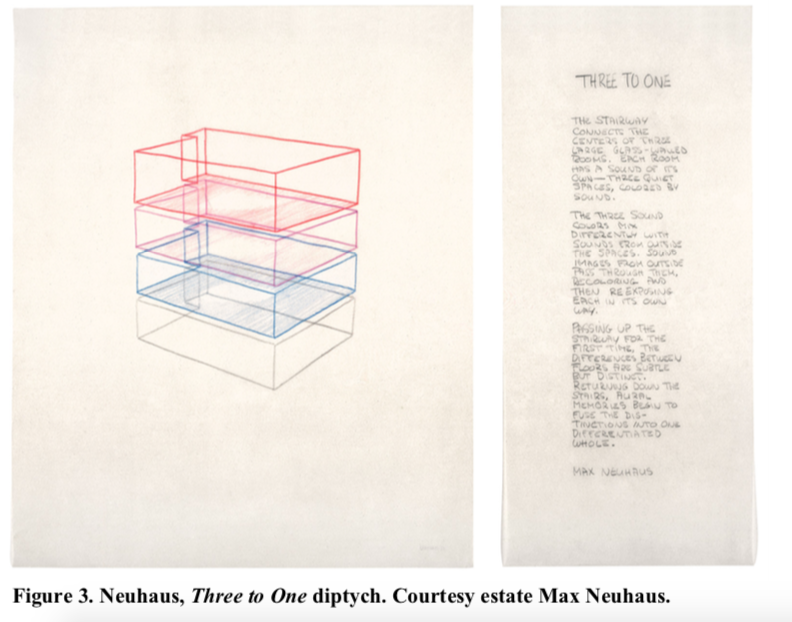

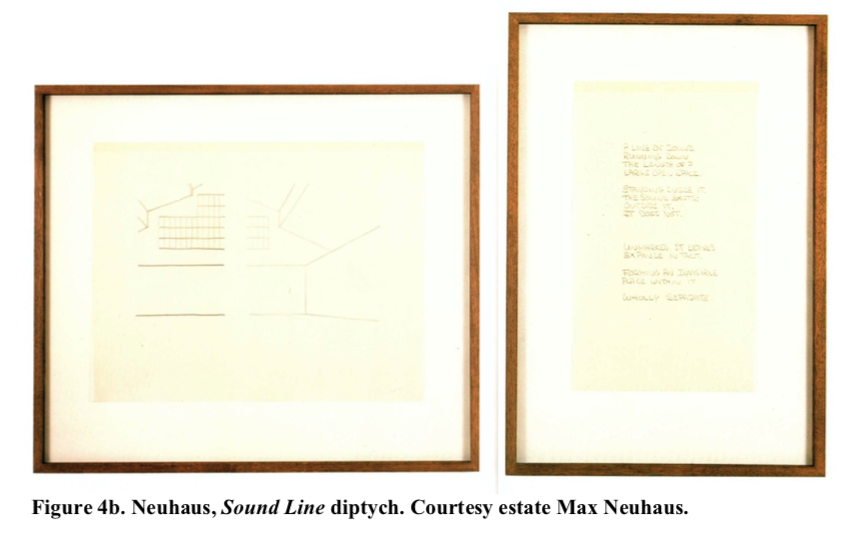

A final category corresponds to that of the diptychs, produced as of the early 1990s, initially for his place-works, namely almost 25 years after the first installations in relation to which they were devised. Although, as Patrick Javault points out, the fact that the drawings were produced such a long time later was undoubtedly motivated by an attempt to “standardize his activity to some extent, as [the drawings] by Christo or Dan Graham [had been able to do] before him” (2018: 51),[5] and, thus, to meet the demands of the art market, Neuhaus himself stated that this relatively long period was due to the time it took “to figure out how to do them without compromising the sound work” (Neuhaus 2003) at the same time as producing a form that constituted both an imprint and a prologue. Unlike the two previous categories, the diptychs do have a close relationship with the work associated with them. On one hand they are presented in the form of imprints in the sense that some refer to works that no longer exist, but, on the other hand, the artist alternately uses the terms “preamble,” “preface,” or “introduction” to the installations in reference to them, even though these drawings were systematically executed after the installations. Through them he in fact aimed to provide an approach to the work in the paradoxical form of feedback that would serve rather as an introduction and that alone would be capable of “pushing presumptions aside to some extent and generating new expectations in order to return . . . the spectator to their initial starting point” (Neuhaus 1992:235),[6] as happens with a loop. As summarized by Ulrich Loock, while the installations belong to a first level, that of the experience, the drawings can be seen as feedback on the experience (Neuhaus 1990:132). Each diptych thus includes “two drawings, one visual and one verbal – a drawn image and a handwritten text hung side by side” (Neuhaus 1994b:10). The text-image association is fundamental here in that it involves two mediums foreign to the installation medium, but also, in the first place, through the incessant toing and froing from one to the other that it triggers, recreating between them, to a certain extent, the same relationship that the diptych itself maintains with its reference installation:

The image and the text that I write are framed in separate frames. Neither is complete. What I mean to say is they can’t stand alone, they only function together, they function very deliberately together. If you start to look at the drawing, there’s too much missing which means you turn to the text. And when you start reading the text you come to a point where there’s also something missing, so you start to turn to the drawing. (Neuhaus 2003)

Evocation versus representation

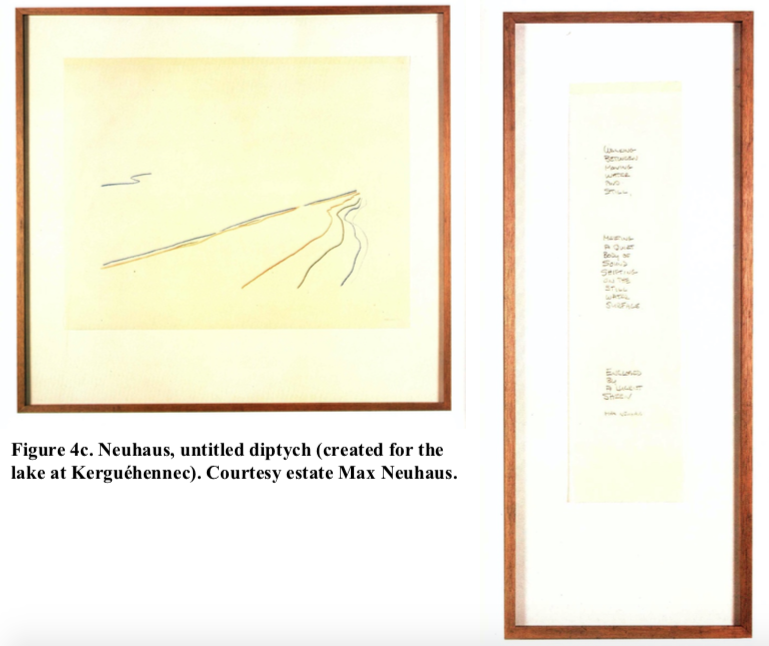

The reciprocal incompleteness of the image and the text allows Max Neuhaus to avoid the risk of representation, calling instead on evocation. In reference to his first exhibition of drawings, presented at Villa Arson (Nice, France) in 1995, he explained that the title chosen, Evoking the aural,[7] was a very exact definition of his approach to drawing in the sense that this medium was about “establishing the form of the idea without placing limits on it” (Neuhaus 2003). Despite their proximity to the works, the diptychs should not be confused with them. They are not a reproduction or a description or even an adaptation of the installations by means of other techniques but are a way of “forming catalysts for individual trains of thought” (Neuhaus 1994a:5). This specificity, sometimes ambiguously formulated in the artist's writings, may have led to misunderstandings about their status. Thus, Greg Desjardins, in spite of being a connoisseur of Neuhaus’ work, is inclined to see “a pictorial presence of the work, a kind of representation” in them. The artist refuted this during his public discussion with Desjardins in 2003 at the symposium ‘Écrire, décrire le son’ at the Domaine de Kerguéhennec in France, conceding that the images “representing the site may be” (Neuhaus 2003), but in no case were the diptychs a representation as a work overall.

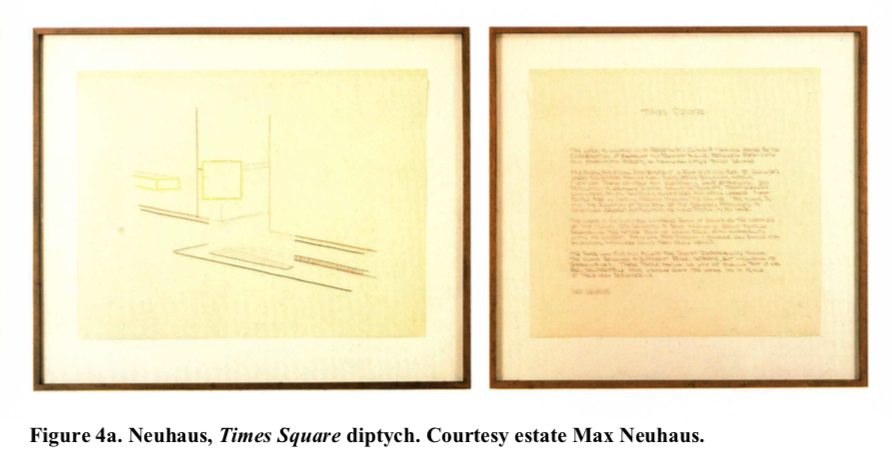

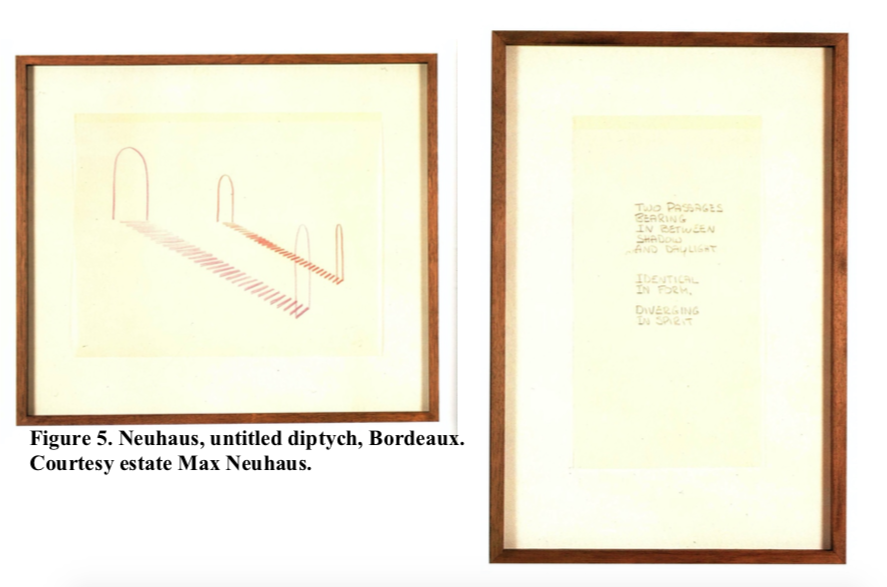

This critique of the diptychs as representations is also there in the refusal to associate colors with pitches or qualities, Neuhaus clearly distancing himself from synesthetically motivated approaches (Neuhaus 2000). While colors are used in some of the diptychs, they only serve to signify different spaces, such as in the drawing of Three to one (Figure 3), the installation created in the AOK Building in Kassel for documenta IX: “I took these three colours to represent the sounds and made drawings that showed what happened, how they spread between [the floors]. But the colour never relates literally to the sound” (Neuhaus 2003). Thus the solution he adopted to nevertheless provide an introduction to the experience offered by his installations consisted quite simply in not seeking to represent their sound component graphically. Sound itself is not drawn, but rather “appears in the drawing as an un-drawn space” (Neuhaus 2003), like in the drawing in the Bell Gallery, but also the diptychs of the works Times square (1977-1992; 2002-; figure 4a), Sound line (1988; figure 4b) or that created for the lake at Kerguéhennec (1986-1988; figure 4c) (Figure 4). While sound is invisible, at least when it is perceived in its usual medium of propagation (the air), Neuhaus’ “construction of places” through his sound installations in fact creates invisible spaces, as evidenced by the poem for the Sound Line diptych.[8]

This non-representation through emptiness was not, however, sufficient for Max Neuhaus, confining the invisible within a register of visibility, even if only through negation, as aesthetically his works go beyond the separation of the senses, a concept that is always problematic by the way. Invisibility requires recourse to a dual medium in order to better disappear. As he told Greg Desjardins, “the problem of drawing something invisible makes this tradition somewhat hard to apply. So I decided to add the written word” (Neuhaus 2003). He went into further detail later in their conversation: “In fact, I rarely draw the sound. I usually leave that to the text part of the drawing. . . .Often the text and the image work so well that you don’t notice the space is not drawn. It leaves space for your imagination” (Neuhaus 2003). Moreover, it is also noticeable that the emptiness of the drawings does not only concern the sound part of the works. Objects, furniture, and even certain architectural elements of the sites are excluded from the drawings, revealing strangely decontextualized spaces, such as the two floating staircases in the diptych produced for the work produced at the CAPC, the Bordeaux museum of contemporary art (Figure 5). It is however above all the individuals themselves, those who frequent these sites, confer a social life on them and who are at the heart of the subject matter the works concern themselves with that prove to be the great absence in these drawings, although we may suppose that such an absence is deliberately arranged so as to leave room for the imaginative presence of those who look at them. With regard to Eugène Atget’s photographs inventorying the streets of Paris, and from which all human presence seems to have disappeared, Walter Benjamin noted: “Not for nothing have Atget’s shots been compared with those of a crime scene. But is not every spot of our cities a crime scene? Every passer-by a perpetrator? Should not every photographer – descendant of the augurs and the haruspices – expose guilt on his pictures and identify the guilty?” (Benjamin 2015:93). Does the fact that Neuhaus gives emptiness such an important place in his diptychs make him a draughtsman of crime scenes? And if so, what crime?

Delineating the apparatuses

The choice of drawing therefore appears to be strategic, opening up a field of possibilities that, according to Max Neuhaus, were prohibited to the other mediums usually used to capture or document a site-specific work. Recording would, for example, result in the loss of a “sense of space” (Neuhaus 1992:152). Similarly, a photograph could not “evoke” the singular experience of these “constructions of places”, namely the perceptual renewal of a space produced by means of the inaudible and the invisible. From this point of view, the artist wrote: “the photograph is useless in describing them; in fact it is a distortion as it overemphasizes the absence of a visual component” (Neuhaus 1994b:10). Conversely, recourse to drawing helped us to grasp this invisible part in itself, to determine the imperceptible presence of these works that call for contextual attention to be redeployed. In a text devoted to Max Neuhaus’ drawings, Yehuda Safran wrote: “We draw to circumscribe that which is invisible, that which we cannot circumscribe – where there is nothing” (1994:8). And in fact, in Neuhaus’ practice, drawing is used as the only medium able to provide what he calls “indicators and tracings of these invisible sound works,” (Neuhaus 1994a:5) or in other words delineations.

In geometry, delineation is none other than the art of displaying contours, of marking boundaries with a single line. It is “the action of tracing out something by lines; the drawing of a diagram, geometrical figure, etc.” (Oxford English Dictionary). Whatever category these drawings belong to, they are similar to map-like forms: technical diagrams of equipment, maps showing the placement of loudspeakers or other sources, architectural cut-outs, drawings of spatial organization, frequency register diagrams, or topographies of sound propagations.

It remains for us to answer the question previously raised, that of the “crime” that these lines draw a map of and, through this crime, to try to define what this invisible criminal element connects to, the sound of which is simply revelatory of it. During the aforementioned Kerguéhennec symposium, a member of the public asked Max Neuhaus a question, which may give a clue: “You erase the drawing in the place where the sound is to be found. Do you do this to evoke the spectator's experience or is it to show the effect of the sound on the space, a kind of breaking down of the space by means of sound?” (Neuhaus 2003).[9] The artist did not really answer this question, or rather did so by avoiding it by means of a digression on the relationship between text and image within the diptychs. By following the intuition of this anonymous attendee, we could argue that the empty spaces and lines of the drawings refer to both the spectator’s experience and the transformation of the space at the same time, but only if we understand them in terms of their relationship to the other lines which connect them and give them their negative presence, in other words in terms of the apparatus to which they belong.

The emptiness is inseparable from the lines that surround it, just as the installations are from the social and acoustic spaces in which they are created.

Notes

[1] Previously published in French in Roven, n°15, May 2020: 34–39.

[2] Sound Installation, David Winton Bell Gallery, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, from February 11 to March 10, 1983.

[3] Neuhaus spoke of these sounds as “like finger snapping”. (Neuhaus 1989: 242)

[4] Our translation of “Quelques semaines après avoir terminé une œuvre, je commence à exécuter quelques dessins pour m’expliquer à moi-même ce que j’ai produit.”

[5] Our translation of “de normaliser un peu son activité, comme avant lui [avaient pu le faire les dessins] de Christo ou de Dan Graham.”

[6] Our translation of “de balayer un peu les préjugés et d’engendrer de nouvelles attentes pour ramener […] le spectateur à son propre point de départ.”

[7] Evoking the Aural/Évoquer l'auditif, Galeries du musée, Villa Arson, Nice, from July 8 to October 1, 1995.

[8] “A Line of sound / running down / the length of a / large open space. / Standing inside it, / the sound exists; / outside it, / it does not. / Unmarked it leaves / expanse in tact. / Forming an invisible place within it / wholly separate.” (Neuhaus 1995:73)

[9] Our translation of “Vous effacez le dessin à l’endroit où se trouve le son. Est-ce pour évoquer l’expérience du spectateur ou est-ce pour montrer l’effet du son sur l’espace, comme une sorte de désintégration de l’espace par le son ?”

References

Benjamin, Walter. 2015. “Small History of Photography.” In On Photography, edited and translated by Esther Leslie, 59–108. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

Javault, Patrick. 2018. “La cloche d’ombre.” D’Ailleurs, hors-série « Max Feed. Œuvre et héritage de Max Neuhaus » 2018: 51–54.

Neuhaus, Max. 1989. “Sound Installations, Techniques and Processes. The Work For The Bell Gallery At Brown University With Asides and Allusions.” In Words and Spaces. An Anthology of Twentieth Century Musical Experiments in Language and Sonic Environments, edited by Thomas DeLio, 233–245. Lanham: University Press of America.

––––––. 1990. “Conversation with Ulrich Loock.” In Elusive Sources and “Like” Spaces, catalogue, 122–135. Turin: Giorgio Persano Gallery.

––––––. 1992. “Entretien par Jean-Yves Bosseur.” In Le sonore et le visuel, edited by Jean-Yves Bosseur, 147–153. Paris: Dis Voir.

––––––. 1994a. “Introduction.” In Max Neuhaus, Drawings. Sound works volume II, edited by Max Neuhaus & Greg Desjardins, 9–11. Ostfildern: Cantz.

––––––. 1994b. “Notes on the Drawings.” In Max Neuhaus, Drawings. Sound works volume II, edited by Max Neuhaus & Greg Desjardins, 9–11. Ostfildern: Cantz.

––––––. 1995. Evoquer l’auditif. Milan/Nice/Rivoli: Charta/Villa Arson/Castello di Rivoli.

––––––. 2000. “Conversation with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev.” Max Neuhaus archives.

––––––. 2003. “Conversation with Max Neuhaus. Greg Desjardins.” Max Neuhaus archives.

Safran, Yehuda. 1994. “Drawing by Ear.” In Max Neuhaus, Drawings. Sound works volume II, edited by Max Neuhaus & Greg Desjardins, 7–8. Ostfildern: Cantz.