NEVA AGAIN: Hip Hop Art, Activism and Education in Post-Apartheid South Africa (Book Introduction)

This book is the culmination of decades of work on Hip Hop culture and Hip Hop activism in South Africa. It speaks to the emergence and development of a unique style of Hip Hop on the Cape Flats – the outlying township areas located within a 25-kilometre range of the city of Cape Town and housing largely working-class black[1] and coloured residents – and, in the case of one chapter, in the Eastern Cape. A distinctive feature of this book is that it weaves together the many varied and rich voices of this dynamic Hip Hop scene to present a powerful vision for the potential of youth art, culture, music, language and identities to shape our politics. These voices have never been read together before, often featured separately in newspapers, opinion pieces and academic essays.

As a challenge to the constraining, colonial nature of academic research and writing, this volume presents academic analyses side by side with, and sometimes privileging, the brilliant insights from the creative minds behind this transformative cultural movement. Throughout the book, we share original artist interviews, panel discussions, and essays written by both the pioneers of Hip Hop in South Africa and the next generation of Hip Hop heads who are active in the culture today. Within these pages, and given the multi-genre, polyvocal nature of this text, we are particularly concerned with understanding how activism comes to shape and define Hip Hop culture in post-apartheid South Africa. Some of the questions we asked as we launched this project were:

» What is the history of Hip Hop activism in South Africa?

» What are some of the strategies that Hip Hop heads employ to sustain their art and activism?

» How do Hip Hop artists rethink the relationship between language, education and power? And how do they transform those relations through their sociolinguistic and educational engagements?

» What are the race, class, gender and sexuality politics of South African Hip Hop? And how do Hip Hop heads deal with the intersectional and transformational politics of the present?

Hip Hop activism can be understood as a form of activism that employs Hip Hop to engage communities critically and creatively with regard to their respective social, economic and political contexts, either through live performance and artistic production (e.g. graffiti, poetry, lyricism, turntablism or breaking) or through educational practices within and beyond conventional schooling (e.g. conducting workshops or developing curricula for alternative forms of education). In a recent work, we contend that ‘hip hop has become a meaningful way for diverse sets of artists, activists and a range of other types of hip hop participants to seize agency in the ways in which they are represented and to make sense of their respective contexts’ (Haupt, Williams & Alim 2018:13). It is a form of practice that challenges the oppression and homogenisation of individuals, groups and communities. It embraces the concept Each One, Teach One – a motto that was taken to heart by young activists during the struggle against apartheid, particularly during the apartheid state’s repression of freedom of movement during the states of emergency. During that historical moment, youth themselves took responsibility for their education in modes of engagement that dispensed with the traditional teacher–pupil hierarchy that was associated with regressive, apartheid-era education. It was during this time that some young activists first realised that ‘conscious’ Hip Hop could be used as a vehicle for them to express their political beliefs. At the same time, young people who were not necessarily politically engaged came to be politically active via the music as well as through their interactions with more politically aware Hip Hop heads, in meeting places such as The Base, which used to run Saturday Hip Hop matinees during the final years of legislated apartheid. The focus was on how to raise the critical consciousness of the Hip Hop community and facilitate ways for artists to exercise agency in the face of social, economic and political restrictions. For South African heads, Hip Hop activism involved translating the culture locally, but also teaching aspects of Black Consciousness, the principles of the Nation of Islam and the fundamentals of the Zulu Nation, among other influential ideologies.

In many respects, this book speaks to how Hip Hop artists, activists and educators have built upon the work of earlier heads to make sense of life in post-apartheid South Africa, a context that continues to struggle with racialised and gendered class inequalities as well as with various forms of interpersonal prejudice – be it gendered, racialised or class-based.

NEVA AGAIN

The book takes its title from Prophets of da City’s (POC’s) song ‘Neva Again’, which was a single on Phunk Phlow (1995), the album released after their third album, Age of Truth, was banned in 1993. The song references the first democratically elected president of South Africa, Nelson Mandela, in his 1994 inaugural speech, by sampling the most famous portion of this speech at the outset of the track. The music video opens with grainy footage of the crew walking the city and then moves into a small lounge where they are watching TV. The camera pans from the TV set to the crew as they watch Mandela intently while he delivers the lines: ‘Never, never and never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another.’[2]

Unlike tracks from Age of Truth, ‘Neva Again’ was aired repeatedly on SABC TV (at the time, the South African Broadcasting Corporation acted as a mouthpiece for the apartheid regime, but made the transition to being a public service broadcaster with the advent of democracy), no doubt in celebration of the nation’s first democratic elections and the victory of the African National Congress (ANC). Shaheen Ariefdien’s opening lines in the song suggest that what is at stake is leadership that truly represents the interests of citizens:

Excellent!

Finally a black president!

To represent

The notions of representation and authenticity are key themes in Hip Hop; artists are expected to authentically represent their experiences and the communities from which they come. Often, the kind of authenticity that is celebrated is linked to representations of working-class black neighbourhoods, or ‘the hood’ (Jeffries 2011). Ariefdien celebrates the authenticity of the president because he represents the interests of black citizens after a hard-fought struggle by youth to both free Nelson Mandela from imprisonment and to secure a democratic state that will serve the interests of civil society – in other words, leadership that is representative. In Hip Hop terms, the president represents. In this regard, DJ Ready D raps that the process of securing and maintaining the gains of the struggle is one that requires constant vigilance and continual revision:

Books and pens are great, Now knowledge awaits Seeka the believer and the believer will become the achiever and the achiever needs to pass it on, knowledge of self is gonna make us strong You made a choice you took the vote Madiba spoke and said ‘NEVER AGAIN’ yes yes sure, we should help the man to make sure that the future stays secure or...REVOLUTION

Ready D’s reference to books and pens alludes to the return to school after years of school protests, boycotts, the detention of youth and skirmishes with riot police and intelligence operatives, as well as to the concept of Knowledge of Self – education is essential to pursuing freedom.

What is worth noting here is that, despite the celebratory nature of this song, Ready D’s verse – which precedes the outgoing chorus’s reference to R&B/funk/disco band Skyy’s celebratory song ‘Here’s to You’ – contains not-so-thinly veiled undertones of the defiance that characterised Age of Truth, which was unyielding in its refusal to accept both the ANC’s and the National Party’s calls to ‘forgive and forget’ in the build-up to the elections (Haupt 1996, 2001). While Ready D raps that citizens should assist the president in securing the nation’s future, he invokes the threat of revolution. This aligns with Age of Truth’s call for revolution as a means of rejecting calls for reconciliation that are not accompanied with a clear plan for distributive and restorative justice in post-apartheid South Africa. When the elections produced a victory for Nelson Mandela and the ANC, they celebrated this victory but also indicated that if the ruling party were to falter, they would not hesitate to engage them critically. The invocation of revolution in the event that citizens do not play an active part in democratic processes could thus be read as a healthy measure of scepticism on their part.

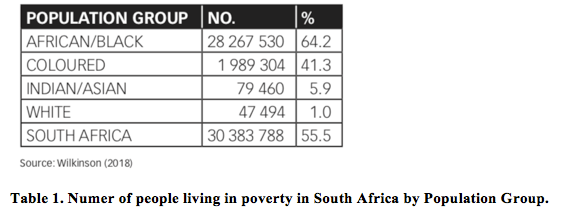

The scepticism in this song as well as on Age of Truth was justified, in retrospect. Mandela’s statement that ‘this beautiful land should [never] again experience oppression of one by another’ is ironic in light of the fact that the ruling party proceeded to embrace neoliberal economic policies. These policies have done very little to reverse the racialised class inequalities that legislated apartheid, produced largely because they place a low premium on public spending and adopt a laissez-faire approach to state regulation of markets (Haupt 2008, 2012). In fact, Africa Check reports that white South Africans are least affected by poverty by a very large margin, while a very large percentage of black and coloured South Africans live in poverty (Table 1).

These statistics challenge the claims made by white right-wing interest groups, such as Solidarity, that white South Africans are living in poverty and that they are being marginalised by a black-led government. They also challenge claims by coloured nationalist interest groups, such as Gatvol Capetonians, that African/black South Africans are being afforded more opportunities than coloured South Africans and that coloured communities are therefore being marginalised.

It is ironic that Africa Check uses apartheid-era racial classifications to demonstrate that inequalities that were produced by apartheid continue to operate along the same racialised lines well after apartheid. For this reason, those apartheid racial categories are useful as indicators of the progress South Africa has made since the fall of legislated apartheid. However, we contend that we should always be wary of using these racial categories without thoughtful consideration of the ways in which race continues to be culturally, politically, socially, legally and economically constructed. It is also ironic that white and coloured nationalist interest groups employ the same categories used to reinforce the apartheid state’s logic of racial segregation to assert that they are being marginalised, while the empirical data clearly undermine their claims. Citizens in the African/black category make up 64.2 per cent of people living in poverty, coloured citizens make up 41.3 per cent, while Indian/Asian make up 5.9 per cent and white South Africans account for just 1 per cent. The figures for African/black citizens are dismal, while the figures for citizens in the coloured category are also cause for concern. While the disparity between coloured subjects and those in the African/black category is significant, it is also apparent that citizens who fall in both categories have a great deal more in common when it comes to class struggles – this has not changed since the decline of legislated apartheid. In effect, the commonalities along class lines make Steve Biko’s (1978:48) definition of Black Consciousness compelling:

We have defined blacks as those who are by law or tradition politically, economically and socially discriminated against as a group in the South African society and identifying themselves as a unit in the struggle towards the realisation of their aspirations.

This definition illustrates to us a number of things:

» Being black is not a matter of pigmentation – being black is a reflection of a mental attitude.

» Merely by describing yourself as black you have started on a road towards emancipation, you have committed yourself to fight against all forces that seek to use your blackness as a stamp that marks you out as a subservient being.

Biko rejected biologically essentialist conceptions of race; instead, he recognised that race serves political and economic functions in a capitalist economy and that it is shaped by these factors. The assertion of blackness is therefore a political one that rejects the internalisation of racist interpellation and dehumanisation, as theorised by Frantz Fanon in Black Skins, White Masks (1967). Biko therefore calls for solidarity between diverse black communities in efforts to oppose racism and systemic processes of marginalisation. His work is thus essential in a context where racial divisions endure and where racialised class inequalities continue to shape the spaces that citizens occupy as well as relationships between communities that still view each other along apartheid-defined racial lines. Further, Biko contends that blackness reflects one’s mental attitude and that one’s emancipation comes from within. This resonates with Hip Hop’s conception of Knowledge of Self – freedom and creativity come from critical introspection and self-affirmation before engaging any given context critically or creatively.

Returning to POC’s sample of Mandela’s historic speech, it is clearly ironic. Their album was banned for advancing a revolutionary message that rejected calls for reconciliation when they rapped lines such as ‘Forgive and forget?/Naa! It’s easier said than done ’cause you stole the land from the black man’. The issue of the land and restorative and distributive justice, along with critical reflections on state violence and repression, are key themes that run throughout the album – and this book. These themes prefigure current debates about gentrification, land reclamation, the assassination of social movement activists, political activists’ so-called ‘land invasions’, state repression of protests in places like Marikana, various township service delivery protests and university protests, the latter having been the site of movements like Fees Must Fall in recent years. A quarter of a century after making it, Mandela’s statement, ‘Never again’, serves to highlight these failures of the state. The oppression of one by another is being experienced again. It is happening again in service of white global capital privilege at the hands of the black elite, ‘whose mission has nothing to do with transforming the nation; it consists, prosaically of being the transmission line between the nation and a capitalism, rampant though camouflaged’ (Fanon 1968:122).

Despite these challenges, Hip Hop artists and activists are exercising their creative and political agency on stage, in the studio, on social media, in workshops, classrooms, panel discussions and in any other available learning space, much like they did in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As we witness throughout the pages of this book, Hip Hop plays a key role in assisting them to redefine themselves on their own terms as well as to renegotiate their relationship with spaces, institutions and hierarchies that position them in ways that potentially limit their agency. Perhaps it is in this regard that the appellation ‘never again’ rings true on an aspirational level. Thanks to transgressive countercultures such as Hip Hop, black subjects (in the inclusive Biko sense of the term) should never again be silenced by repressive practices.

OUTLINE OF THE BOOK

This book includes photographic work by Ference Isaacs to present examples of the visual and performative modalities of Hip Hop. It also includes images supplied by Emile Jansen and Heal the Hood, given their intimate relationship with artists and activists over the years. In this regard, the book is also associated with music produced by a collective of Hip Hop and jazz musicians who call themselves #IntheKeyofB. The recording project began as a community event that was produced by former Brasse Vannie Kaap (BVK) b-boy, Bradley Lodewyk (aka King Voue), to lay claim to his neighbourhood, Bonteheuwel, as a creative space in the face of ongoing gang violence and negative press coverage that largely associated it exclusively with violent crime. The recording project led to the production of an extended play (EP), co-produced by Gary Erfort (aka Arsenic), Lodewyk and Adam Haupt, and explores themes such as gun violence, toxic masculinity, racialised poverty, racism, gentrification, government corruption, and language and identity politics. Many of these themes speak to aspects of the book and feature a range of MCs as well as instrumentalists who perform jazz and R&B. The project is unique because it brings Hip Hop artists both into the studio with and onto the same stage as instrumentalists and singers from other genres. Despite the key artistic differences in this collective, all artists have one thing in common: they are from the Cape Flats, a space that has hegemonically been represented in racially stereotypic ways. In many respects, this creative collaboration defies those stereotypes.

The other parts of the book are introduced below.

PART ONE: bring that beat back: Sampling early narratives

The chapters in Part One provide a decolonial perspective on our present times. Hip Hop is intricately bound up with the story of enslavement and colonisation and is profoundly political. It has been politicised from its inception and its precursors, the cultural practices that preceded Hip Hop, are signifyin(g), as Henry Louis Gates Jr theorises it in his books The Signifying Monkey (1988) and Figures in Black (1987). Signifying and playing the dozens. Verbal insults, verbal duelling, wordplay, the punchline – all of these things are not actually specifically Hip Hop cultural practices; they precede Hip Hop. They come from playing the dozens.

In this section, there is a strand of Hip Hop activism that is closely tied to the black nationalist narrative associated with places like the South Bronx, narratives that played an important role in uniting people across a range of boundaries in South Africa. Blackness became a unifying signifier that brought together people who were undermined, who were exploited and marginalised by colonialism. Black nationalism unified diverse groups under a broad, inclusive banner of blackness. Thus, if in Cape Town, for example, the apartheid state positioned people as either coloured or black (Zulu, Xhosa or Sotho), black nationalist narratives rejected what they viewed as ‘divide-and-conquer’ strategies by, as Public Enemy’s Chuck D famously rapped, ‘the powers that be’. For many Hip Hop heads at the time, even if they self-identified as coloured, they also recognised themselves as being part of the broader black experience – that is, colouredness was viewed within the spectrum of blackness, not separate from or superior to blackness.

In reading the chapters in Part One, it becomes evident how groups like Prophets of da City, Black Noise and Godessa were able to tap into the concept of Knowledge of Self as they developed their various Hip Hop artistic practices. The chapters not only inform the reader about the importance of Knowledge of Self, and Hip Hop art and activism, but they do so while exploring the role of the DJ, MC, dancer and graffiti writer. The aesthetics of Hip Hop are not separate from its politics. In fact, as Tricia Rose argues (ironically, in 1994), the aesthetic is political in Hip Hop because Hip Hop privileges black cultural priorities where whiteness insists on hearing only ‘black noise’.

The insightful interviews conducted by Adam Haupt with the pioneering artists of South African Hip Hop open up a range of conversations about life under apartheid, and the role Hip Hop played in the development of a distinctly local style that served to celebrate life under, as well as resist, those oppressive conditions. Interviews with POC, and pioneering DJs Azuhl and Eazy, demonstrate that while often DJs are the most underrated standard-bearers of Hip Hop, they nevertheless push the culture to sample new ways of art(ing) and engaging in activism. From developing a new performance of ‘baby scratch’, ‘landing a toe’ and ‘nose on vinyl’, to new ways of sampling, the DJ is, as DJ Ready D explains, invested in the advancement of Knowledge of Self and focused on dispelling ignorance through performance. While the MC’s job is to advance Hip Hop through the word, what is clear from the interviews is that DJs are also known for their lyrical ingenuity and linguistic creativity. This interplay between the DJ and the MC – both functioning as ethnographers of Hip Hop culture, if you will – is produced through various artistic genres and modes that both archive and evolve particular politics and knowledges. A prime example of this kind of artistic work – this aesthetic activism of sorts – is Godessa’s pioneering music and lyricism. As an all-woman Hip Hop crew, they not only contested the sexual politics of Hip Hop, but also challenged sexism, racism and classism in the broader society.

Today, breakdancing is a dominant element of South African Hip Hop. This is in no small part due to the exhaustive efforts of Heal the Hood, and its pioneer Emile YX?. In a trailblazing chapter about the history and future of breakdancing as a Hip Hop element, Emile YX? demonstrates vividly that South African Hip Hop developed into a versatile culture during apartheid, producing new genres of breakdance pops, locks, top rocks, and contemporaneously krumping or jerking, while uniting diverse participants into inclusive dance circles, and conceiving of this circular arrangement as a metaphor for social inclusion. The future of Hip Hop culture in South Africa, as Emile YX? points out, will require the next generations to redouble their activism by putting thought into action.

The photographic work about Mak1One’s graffiti, compiled by Ference Isaacs (with assistance from Heal the Hood) and interspersed throughout the book, reintroduces the reader to the multimodality of graffiti, the one element of Hip Hop that through pictures has always conscientised the larger South African public. Graffiti artists provide a stylistic image comprising icons and figures, guiding the viewing public toward the stylistic repertoires and political messages of Hip Hop art and activism. And nowhere is this made clearer than in the ALKEMY interviews that Haupt conducted with Nazli Abrahams and Shaheen Ariefdien.

The graffiti artist is, like every participant in Hip Hop, self-critical and self-reflexive about the objects in their ‘throw-ups’ and ‘pieces’, focusing always on stylistic clarity but subtly (or explicitly) underwritten by challenging symbolic power. Graffiti artists are concerned with a Hip Hop ethnography of ocular aesthetics: how to conduct research from an empty canvas to producing a beautiful graffiti piece that stimulates our visual repertoires. And through this process, graffiti artists paint the diversity of our urban landscapes and provide the air to Hip Hop art and activism as a novelist would.

PART TWO: Awêh(ness): hip hop language activism and pedagogy

In an interview with Marlon Burgess (Ariefdien & Burgess 2011:235), Shaheen Ariefdien said the following in relation to Hip Hop language style and politics:

[Cape Town] Hip Hop took the language of the ‘less thans’ and embraced it, paraded it, and made it sexy to the point that there is an open pride about what constituted ‘our’ style...to express local reworkings of hip-hop.

These words provide a cogent and concise definition of South Africa’s Hip Hop art, activism and education with respect to language. For decades, Hip Hop artists have honed, through individual effort and community gatherings, a South African style of Hip Hop based on ‘the language of the “less thans”’. This was an important phase in the localisation of the culture. Once the local scene found its voice, the artists who then became activists both interrogated and embraced the marginality of that voice, and they began to remix and amplify that voice.

But what happens when you really take on the plight of voiceless people, the language of the less thans, and make it form part of the principles and values of your art, activism and education? The chapters in this section, a rich collection of interviews, essays and panel discussions, dig into the linguistic, pedagogical and meaning-making systems of South African Hip Hop culture – not only in various distinctive styles but also reaching across cultural and racial borders to connect with other voiceless people. Contributors open up debates about supporting the culture’s multilingual speakers, South African Hip Hop rhyming for a global stage, and methods of developing the agency and voice of the marginalised via transformative language education and policies. Take for example the reflections on South African Hip Hop’s multilingual activism, that is, the process of establishing and identifying translingual means to produce new voices. The first few chapters demonstrate that various ways of speaking, used across a variety of languages, spaces and places, can be meaningful tools for empowering people of colour in contemporary South Africa, and for counteracting the raciolinguistic profiling and discrimination faced by many of the nation’s citizens in educational and other institutions.

As artists explain in these chapters, historically multilingual activism has always been a feature of South African Hip Hop. It has increased the mobility of Hip Hop artists, and allowed them to transcend borders and boundaries. Often, artists had to move across geographical locations to share in the inter-/cross-cultural voices and speech varieties of their neighbours and other communities. As Alim, Ibrahim and Pennycook (2009) argue in Global Linguistic Flows: Hip Hop Cultures, Youth Identities, and the Politics of Language, this kind of linguistic sharing, combined with Hip Hop’s demand for linguistic innovation, creativity and a broader ‘rule-breaking’ ethos that eschews tradition, has made for some unique challenges to education and language policy-makers. Just as artists have and continue to ‘remix multilingualism’ (Williams 2017), educators will have to develop new, innovative pedagogies that allow communities to sustain these rich, globally influential language practices. Contributors in this part argue for a break from the eradicationist pedagogies of the past (those that erased our language varieties in the name of upward mobility) and a move towards the sustaining pedagogies of the future.

PART THREE: Remixing race and gender politics

What happens when you speak out on racial and gender discrimination through Hip Hop art, activism and education? This question is answered by a number of sharp and critical intersectional reflections by some of South Africa’s Hip Hop artists, activists and pedagogues. The chapters provide strategies on how to counter the hegemonic forces of racism, sexism and homophobia and how to challenge discrimination across society. Contributors demonstrate in detail how Knowledge of Self helps keep the oppressive politics of race, class and gender in check. However, as with all cultural practices, inward reflection on race and gender is sometimes overlooked, which is often the case when it comes to gender and sexuality in the male-dominated domains of Hip Hop. Within these pages, however, artists move beyond characterisations of Hip Hop culture as inherently sexist and misogynistic. Artists and activists have begun to take the intersections of race, gender and sexuality seriously and are arguing for a Hip Hop that is inclusive of all bodies: straight, queer, dis/abled and non-binary.

With the success of artists like Andy Mkosi and Dope Saint Jude, along with community- organising efforts by Natasha C Tafari (all featured in this part), among many others, Hip Hop culture continues Godessa’s earlier efforts to remix gender mindsets, reframe the way we talk about gender and sexuality, and the way we represent the body. As we witness throughout these pages, a new generation of Hip Hop artists has emerged and is committed to taking an intersectional approach to race, class, gender and sexuality through a re-engagement with the histories and legacies of Hip Hop culture and our broader communities. This powerful, transformative work within Hip Hop has the potential to influence social transformation beyond Hip Hop, for, as Andy Mkosi warns in her interview with H Samy Alim: ‘Everywhere you go, all these spaces, they’re problematic. We all problematic.’

PART FOUR: Reality check: The business of music

Part Four of the book provides participants’ views on the ways in which aspiring artists can navigate careers in a music industry that, historically, has been shaped by unequal relations of power along the lines of race, gender and class, both during and after the colonial era. It ends with a scholarly reflection on the ways in which the challenges in the music industry resonate with those faced by scholars in the academy. Ultimately, foundational changes need to be made on a macroeconomic level to address inequities in both the music industry and the academy. Provocatively, the final chapter in this section argues that the problem of corporate monopolisation in the music industry is similar to the problem of corporate monopolisation of scholarly publishing, to the extent that democratic rights to free speech and academic freedom are undermined. Ultimately, it argues that if calls for the decolonisation of knowledge are to be heeded, knowledge needs to be decommodified.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it is important to note that this book is unique precisely because it decentres the voices of the scholars who have long been writing about Hip Hop. This is a first for South African Hip Hop scholarship. The book’s multi-genre approach, which arranges writing by theme and not by genre, is intended to decentralise the authority of the scholars in this edited volume – to place academics alongside the contributions of the artists and activists who have cut, mixed and remixed Hip Hop politics, activism and aesthetics to speak to their specific respective locations and agendas. We recognise, as Alim – influenced by Spady’s (1991) ‘hiphopography’ – wrote, that Hip Hop artists are not merely cultural producers and consumers. They ‘are “cultural critics” and “cultural theorists” whose thoughts and ideas help us to make sense of one of the most important cultural movements of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries’ (Alim 2006:11). This is why we insist on direct engagement with the cultural creators of Hip Hop.

Multiple voices, which appear as authors and co-authors, feature here in the tradition of Hip Hop’s polyphonic approach to music production – from the lyricist dropping 16 bars of verse, which feature multisyllabic rhymes that are often intertextual and layered, and who may share a track with other MCs and singers (itself polyphonic); to the producer who samples music and media from a range of sources to create new music and media forms (more polyphony); to the DJ whose turntablism cuts, mixes and scratches a range of sounds and voices to move the crowd (yet more polyphony); to the graff artist whose textual and iconic styles of production often reference a range of media and texts (polyphony of a visual and textual kind, cutting across modalities); and to the breakdancer interpreting and remixing a range of cultural references, histories and dance styles (polyphony in yet another modality).

This volume is therefore like a park jam or block party, bringing together many voices, styles and modalities in ways that can be both celebratory and unpredictable. We have designed it this way in an intentional effort to claim public spaces that appear to be hostile to black, working-class subjects, the academy included. Or better still, as is the case with the #IntheKeyofB EP associated with this book, we present a polyphony of voices and styles in order to sample, cut and remix what counts as scholarship in a context where scholars are debating what it means to decolonise the academy and challenge hegemonic approaches to knowledge production, distribution, teaching and learning. Like the block party and the park jam, this edited volume is meant to produce scholarship that claims hegemonic spaces that are historically hostile to black modes of thought and articulation in an effort to rethink and remix our understanding of scholarship.

Notes

[1] In this book, we define the racial categories of black and coloured as colonial and apartheid constructs created to design an unequal South African society. As with Haupt’s book, Static, the editors of the volume view race as socially and politically constructed. We take our cue from Zimitri Erasmus, the editor of the seminal work Coloured by History, Shaped by Place: New Perspectives on Coloured Identities in Cape Town. In an editor’s note prior to the introduction of the book, Erasmus frames the work’s exploration of ‘coloured’ identity politics in the following way: There is no such thing as the Black ‘race’. Blackness, whiteness and colouredness exist, but they are cultural, historical and political identities. To talk about ‘race mixture’, ‘miscegenation’, ‘inter-racial’ sex and ‘mixed descent’ is to use terms and habits of thought inherited from the very ‘rare science’ that was used to justify oppression, brutality and the marginalisation of ‘bastard peoples’. To remind us of their ignoble origins, these terms have been used in quotation marks throughout. (Erasmus 2001: 12) Erasmus refutes biologically essentialist thinking on race that was employed to justify racist oppression during the colonial occupation of Africa as well as during 48 years of apartheid in South Africa. In order to make her position clear, she elects to include the editor’s note as well as to use a number of contested terms in quotation marks throughout the edited volume. Neva Again does not employ the use of quotation marks throughout, but the editors hope that this note suffices to signal its position they view racial identities as culturally, historically and politically constructed.

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vhN_GzCbH0I

References

Alim, H. Samy. 2006. Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip Hop Culture. New York: Routledge.

Alim, H. Samy, Awad Ibrahim and Alastair Pennycook, eds. 2009. Global Linguistic Flows: Hip Hop Cultures, Youth Identities, and the Politics of Language. New York: Routledge.

Ariefdien, Shaheen and Marlone Burgess. 2011. “A Cross-generational Conversation about Hip Hop in a Changing South Africa.” In Native Tongue: An African Hip Hop Reader, edited by Paul K. Saucier, 219-252. New Jersey: Africa World Press.

Biko, Steve. 1978. I Write what I Like. Gaborone: Heinemann.

Fanon, Frantz. 1967. Black Skins, White Masks. New York: Grove Press.

Fanon, Frantz. 1968. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press.

Gates, HL Jr (1987) Figures in black: Words, signs, and the “racial” self. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gates, Henry Louis Jr. 1988. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Haupt, Adam. 1996. “Stifled Noise in the South African Music Box: Prophets of da City and the Struggle for Public Space.” South African Theatre Journal 10(2):51-61.

Haupt, Adam. 2001. “Black Thing: Hip-Hop Nationalism, ‘Race’ and Gender in Prophets of da City and Brasse vannie Kaap.” In Coloured by History, Shaped by Place, edited by Zimitri Erasmus, 173-191. Cape Town: Kwela Books & SA History Online.

Haupt, Adam. 2008. Stealing Empire: P2P, Intellectual Property and Hip-Hop Subversion. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Haupt, Adam. 2012. Static: Race and Representation in Post-Apartheid Music, Media and Film. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Haupt, Adam, Quentin E. Williams and H. Samy Alim. 2018. “It’s Bigger than Hip Hop.” Journal of World Popular Music 5(1):9–14.

Jeffries, Michael P. 2011. Thug Life: Race, Gender, and the Meaning of Hip-Hop. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rose, Tricia. 1994. Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Spady, James G. 1991. “Grandmaster Caz and a hiphopography of the Bronx.” In Nation Conscious Rap: The Hip Hop Vision, edited by James G. Spady and Joseph Eure. Philadelphia: Black History Museum Press.

Wilkinson, Kate. 2018. “FACTSHEET: South Africa’s Official Poverty Numbers.” Africa Check, 15 February. Accessed September 2018, https://africacheck.org/factsheets/factsheet-south-africas-official-poverty-numbers/

Williams, Quentin E. 2017. Remix Multilingualism: Hip Hop, Ethnography, and Performing Marginalized Voices. London: Bloomsbury.