Parallels of Psycho-Physiological and Musical Affect in Trance Ritual and Butoh Performance

Biography

Michael Sakamoto is an interdisciplinary artist active in dance, theater, performance, and media art. His work has been performed and exhibited in Thailand, Mexico, and throughout Europe and the USA. He is the recipient of numerous grants, including from Meet the Composer, Asian Cultural Council, Japan Foundation, California Community Foundation, Arts International, and DanceUSA. He is currently pursuing an MFA and Ph.D. in the UCLA Department of World Arts and Cultures. For more information, go to www.michaelsakamoto.com.

From ancient times to the present, religious and cultural rituals involving trance, ecstatic states, spirit possession, shamanic journeying, and myriad forms of music and sound have gripped societies large and small the world over. Millions of participants throughout history have directly experienced the affects and effects of such practices. However, due to the inherently ineffable nature of what we might refer to as the realm of spirit or universal energies, there has remained from time immemorial a tenuous relationship between these pursuits and intellectual analysis and understanding of them. In the 20th Century, however, with the advent of interdisciplinary approaches to scholarship as well as participatory ethnographic methods of research, there has developed something akin to a groundswell of deeper examination and comprehension in the academic, scientific, and aesthetic arenas. No longer generally considered the purview of religion and religious studies, the study of trance and ecstatic rituals relates directly and indirectly to traditional and contemporary mythologies and social narratives in a way that can both enlighten minds and elicit controversy.

In order to examine how such rituals might symbiotically relate to and reflect upon secular performance practices and how significant music is within both, I will draw comparative parallels between a number of fundamental concepts and practices in trance and ecstatic rituals from around the world and the contemporary performance form known as Butoh dance. In both form and character, Butoh shares many commonalities with various structures of ritual affliction, possession, and journeying, and the use and purpose of music in Butoh is also highly similar to that within various rituals.1 Additionally, I will attempt to highlight sociological concepts active within both spirit-based rituals and Butoh in order to draw active conclusions about the relevance of both to the “real world,” regardless of how the latter is defined or who defines it.

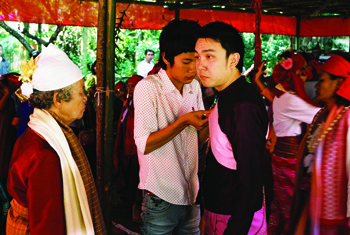

Michael Sakamoto and Amy Knoles perform "Sacred Cow," a dance-theater exploration of sacred and profane embodiments, at REDCAT, Los Angeles, 2006.

Butoh Performance and Practice

The dance performance form known as Butoh has, since its inception 50 years ago, been subject to gross generalizations and stereotyping in regards to its metaphysical and spiritual core. Despite decades of increasing notoriety within its root Japanese culture, it continues to exist there in a largely marginalized status, a somewhat unclassifiable medium, a dance usually without strict choreography and an aestheticized ritual without any underlying religion or defined spiritual practice. In the West, it is looked upon generally as a fascinating Orientalist conundrum and largely untransferrable to rationalist academic forms of performance pedagogy. Notwithstanding the audience and critical success of Butoh artists on Western concert stages, very few scholarly analyses have been published.2

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, A young choreographer-dancer, Tatsumi Hijikata, in loose partnership with an older counterpart, Kazuo Ohno, methodically fashioned an alternative form of dance theater entitled, Ankoku Butoh, or “dance of darkness,” later shortened to simply Butoh. Throughout his career, Hijikata developed methodical and ritualistic dance and performance techniques for accessing psycho-physiological states aligned with bodily and metaphorical concepts of a human and spiritual nature concealed underneath a mind/body hyper-socialized by rapid modernization. Hijikata came to refer to this a “body in crisis,” and Butoh artists came to portray a contemporary psychic crisis in Japanese society via deconstruction, absurdity, and darkness.

Butoh practitioners were forced to develop methods for maintaining cultural and spiritual memory through means alternate to Western culture’s emphasis on the directly-descriptive, written word, which marginalized nonverbal modes of remembering and knowing. They accomplished this challenge largely by retreating to the core of human being, i.e. centering memory and identity within an active body highly self-conscious of its socialized habits.

Butoh artists then and now largely promote an off-balance, asymmetrical, and methodical form in an almost primal or “un-learned” mode, aimed at exposing, struggling through, and resolving deeply embodied societal ills and unearthing and clarifying a kind of root intuitive self, pre-verbal, experiential, and unpredictable. A core intent of Butoh practice is to reintegrate a mind/body functionally divorced by socio-cultural forces and realize a state of total awareness where one’s moment by moment perspective reaches deep within as well as far outside to the reality of the surrounding world as directly experienced. Artists attempt in each fleeting moment to peel away at psycho-physiological tendencies rooted in social structures, spontaneous perception unmasking preconception.

One way in which Hijikata came to create such a method was by taking inspiration from his own perspective on the traditional agrarian Japanese body and its physicality to inspire his original concept of Butoh. In speaking of the core of Japanese folkloric dance, he stated:

If in fact one were to remove from their dance both the hardship and the cruelty they endured, very little would remain. The origins of Japanese dance are to be found in this very cruel life that the peasants endured. I have always danced in a manner where I grope within myself for the roots of suffering by tearing at the superficial harmony…thinking about the strangeness of our bodies or manipulating them through various training techniques is not enough. (cited in Viala and Masson-Sekine 1988:185)3

Thus, like contact improvisation and many forms of postmodern dance since the 1960s and unlike forms of dance previous to that era, Butoh does not strictly adhere to any specific movements, postures, steps, or images. There is no set physical or aural vocabulary universal to all or even the majority of Butoh artists. Rather, Butoh is at root about the relationship of one’s body to society, the world around it, and to itself. Essentially, Butoh movement, choreography, staging, soundscores, and other performative elements are for the most part drawn from how a specific artist or group relates their mind/body instrument in any given moment or time period to the specific themes or content of a performance. Therefore, over the course of multiple performances, often day by day, how a dancer performs a work changes regularly, and sometimes drastically.

Butoh form is therefore practically impossible to define. Despite the fact that the classic image of the Butoh dancer has become one of a body painted white, crouched low and off-balance, moving painfully slow or methodical in painful fits and starts, this is simply a stereotype and an image that has caused many younger dancers to adopt the Butoh label as a style as much as a form of dance. In reality, there are as many Butoh dancers creating work without white makeup, with a high center of gravity, and with movement akin to many other forms of eastern and western dance. What they all have in common, however, is an approach to the body, which acknowledges and follows the mind/body’s constantly evolving existential circumstances.

Though Hijikata did come to notate a general system of image and poetic language-based training in his later years, he specifically rejected the systematization of specific movement to define his form of performance: “In the Stanislavski system or in the techniques of other national dances, it is to a certain degree that such and such an effect can be produced, that the articulation can be categorized…thus man finds himself in a narrow and constricted world” (cited in Viala and Masson-Sekine 1988:185).

As a teacher, Kazuo Ohno would often encourage his students to forego premeditation when creating movement and trust their instincts to discover the logical course their body should follow in order to integrate within itself and to the realm outside: “Rather than analyzing your movements…push yourself right to the very edge of sanity…Our dance becomes godlike once the ghosts of the universe surge forth from the depths of our consciousness” (Ohno and Ohno 2004:291).

In relation to ritual and trance studies, Butoh is an aesthetic form of embodiment situated between and sharing aspects of both the identificatory state of possession and the window-opening/journeying state of shamanism. How it accomplishes this, how music at times plays a major role in its process of embodiment, and how it functions socio-culturally are the main areas of discussion in this article.

Between Character and Possession

Butoh resembles possession through its utilization in training and performance of magical, spirit-like imagery and imagining of metaphorical and symbolic possession by animist-oriented entities based in archetypal character, spirit, or animal forms and held in a crisis state (e.g. angst-ridden salaryman, tree monkey unable to climb, hungry ghost, etc.). Hijikata’s techniques were all directed towards a greater connection and understanding between, not only performer and audience, but “the self” itself and the world around us: “Butoh…plays with perspective, if we, humans, learn to see things from the perspective of an animal, an insect, or even inanimate objects. The road trodden everyday is alive…we should value everything” (cited in Viala and Masson-Sekine 1988:65).

Parallels also exist between Butoh and shamanism in that both forms function as energetic focal points, or windows, onto a realm of nature, shadow, and impermanence. Both shamanic initiation and Butoh training attempt to move their participants past normative usage of sets of acquired behaviors, i.e. to a “post-socialized” mode of action as agents of personal and social healing and change.

Butoh’s use of possession and shamanic-like states stands in a direct lineage with myriad popular forms of drama and performance, such as classical Chinese drama, Greek old drama, and comedies of Restoration England to name but a few (Kirby 1976:147). These and other modes of performative expression employ a dialogic structure between comedy and grotesquerie that is parallel to disease spirits in numerous shamanic practices as well as the use of behavioral sets of socialized mind/body aspects in Butoh:

The physically grotesque distortion that derives from the representation of disease and abnormality then becomes transposed into caricature of social types… Comedy represents the antagonist in social and psychological terms, but it is a pattern based on the shaman’s antagonism to disease spirits, that which is to be driven away or eliminated. (Kirby 1976:147)

This relates directly to character development in Butoh performance, where artists often search for facial expressions and ways of handicapping their movement and seeming ability onstage to convey an absurdity of tragic proportions. As Hijikata states: “I’m convinced that a pre-made dance…is of no interest. The dance should be caressed and fondled; here I’m not talking about a humorous dance but rather an absurd dance…it is a mirror which thaws fear” (cited in Viala and Masson-Sekine 1988:185).

Sinking into a self-contradictory, dialectic state between an absurd, tragicomic surface full of recognizable details and an interior “soul” dusting itself off after years of neglect, these characters then typically transform into painfully engaging and often entertaining double images, seeking resolution in a situation where the only possibility is to dance one’s way out of this double knot. Kirby cites a similar case with Ceylonese clowns, who:

Express bizarre, psychotic thinking and sense confusion” because these are aspects of the diseases they are representing and treating…The awesome, violent, and horrible aspects of the demon are first emphasized, but when he appears in the performance his behavior is comic. Obeyeskere observes that “these inversions not only ease the interaction situation, but prevent the attitudes one has towards demons in ordinary life from being generalized into the ritual situation. (Kirby 1976:147-148)

The aspects of possession and shamanic trance ritual most relevant to a comparison with Butoh are 1.) shamanic initiation as a curative process for personal affliction and 2.) shamanic and possession ritual as either preventative or curative of social affliction.

In Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstacy, Mircea Eliade enumerates a long roll call of tribal shamanic practices from across multiple continents, all of which possess highly similar initiatory states for individuals “destined” to become shamans: “Usually sicknesses, dreams, and ecstasies in themselves constitute an initiation; that is, they transform the profane, pre-‘choice’ individual into a technician of the sacred” (Eliade 1964:33).4 Citing phases of affliction, journeying, death, empowerment, and rebirth, Eliade draws direct concrete parallels in a wide range of initiatory rites from around the globe, all rooted in distinct populations separated by language, custom, culture, and geography. From the Yakut, Samoyed, Tungus, and Buryat of Siberia to Australian Aborigines to the Yamana and Cobeno of South America, Eliade finds the same narrative principle at work, “the central theme of an initiation ceremony: dismemberment of the neophyte’s body and renewal of his organs; ritual death followed by resurrection,” (Eliade 1964:38) and breaks it down thusly:

Certain physical sufferings find their exact counterparts in terms of a (symbolic) initiatory death…the dismemberment of the candidate’s (the sick man’s) body, an ecstatic experience that can…be brought on by the sufferings of a “sickness-vocation” or by certain ritual ceremonies or…dreams…followed by a renewal of the internal organs and viscera; ascent to the sky and dialogue with the gods or spirits; descent to the underworld and conversations with spirits and the souls of dead shamans; various revelations, both religious and shamanic. (Eliade 1964:34)

In my own fieldwork on Northern Thai spirit mediums, I have found a similar tendency. In interviews, numerous mediums have alleged that they first became aware of a connection to the spirit realm via an initial chronic state of sickness, even to the point of hospitalization. Seemingly only after ceremonial acts of ancestor worship and appeasement were they able to return to and maintain a healthy state.5

Moreover, what is perhaps just as fascinating is that the basic process at the root of Butoh training and/or performance is structured in a similar manner. Hijikata spoke repeatedly throughout his career of the schizophrenic nature of the socialized body:

This cast-off skin is our land and home… totally different from that other skin that our body has lost… One skin is that of the body approved by society. The other skin is that which has lost its identity. So, they need to be sewn together, but this sewing together only forms a shadow. (cited in Hoffman and Holborn 1987:121)

Butoh training employs complex methods of unearthing culturally-learned states of mind-body-spirit dissociation and dis-unity that underlie the recursive processes in Butoh that feed into resituation and empowerment. This may begin, for example, with exposure to fantastic imagery and intense, visceral, emotional experience. Metaphorically and literally, Hijikata made grenade-like pronouncements such as “Butoh is a corpse standing straight up in a desperate bid for life,” (Hijikata 1993:58) or, “When I begin to wish I were crippled – even though I am perfectly healthy – or rather that I would have been better off crippled, that is the first step towards Butoh” (cited in Viala and Masson-Sekine 1988:75). At times, he even employed a writing style for program notes and published articles that employed abstract, transgressive language to get his point across and inspire his students to find their inner, hidden spirits untouched by a technologized urban modernization:

Wearing an apron, I go into service in the classification of fat that must be shaved away. To slaughterhouses, to schools, to public squares. The dismantling ceremony must be quickly carried out…bodies that have maintained the crisis of the primal experience celebrate their mutually dizzying encounter…Under a vivid sign the material and I take our first step to the treatment site for movement while anticipating various things in giving up our lives to a sweaty “engagement.” (Hijikata 2000:41)

Butoh artists at root engage in psycho-physiologically dissociative states highly similar to the locus of mental imaging in initiatory shamanic journeying, i.e. a place of affliction, dismemberment, psychic death of the crisis body and rebirth into a newly empowered state of being able to resist all manner of personal and social ills. A direct parallel structure between shamanic initiation and Butoh training and performance might be listed as follows:

Shamanic Initiation |

Butoh Training/Performance Process |

Like any person who has seen much in the ways of life, the newly-endowed shaman, having experienced the spiritual plane, has come to incarnate the connection between worlds and the awareness that comes with such ability: “Like the sick man, the religious man is projected onto a vital plane that shows him the fundamental data of human existence, that is, solitude, danger, hostility of the surrounding world” (Eliade 1964:27).

Hijikata makes similar observations early in his formation of Butoh philosophy:

Within shelves exposed to view where the body lies in state, eyes intervene in the current generation whose soul too is unable to live merely through the succession of property. I eventually arrive at my material by carefully walking around Tokyo where the generation whose hands made eyes has not altogether died out. (Hijikata 2000:40)

In other words, Hijikata is searching for those “pre-modern” individuals with eyes that can see, i.e. those from a generation of non-mechanized bodies, just as a shaman or medium might search out or embody ancestor spirits with whom they can communicate about communally-shared afflictions.

Moreover, the ancestor spirits typically involved in shamanic initiations are not only involved in the curative aspect of the ritual, but then remain in an ongoing relationship with former neophytes as their guardian spirits:

The future shaman is cured in the end, with the help of the same spirits that will later become his tutelaries and helpers. Sometimes these are ancestors who wish to pass on to him their now unemployed helping spirits. In these cases there is a sort of hereditary transmission; the illness is only a sign of election, and proves to be temporary. (Eliade 1964:28)

This may also be compared with the tradition in Butoh practice established by Hijikata of energetically, mentally, or literally communing on some level with one’s ancestor spirits:

I would like to make the dead…dead again…to have a person who has already died die over and over inside my body…I often say that I have a sister living inside my body. When I am…creating a butoh work, she plucks the darkness from my body and eats more than is needed…She’s my teacher. (Hijikata 2000:77)

Kazuo Ohno also took primary inspiration from the dead: “The spirits of the dead have taken refuge in my body…I am who I am thanks to all those who paved the way for me…On slipping into the sleep of the dead, I penetrate their dreams of the past and the future” (Ohno and Ohno 2004:267-269).

Hijikata often spoke of maintaining this active relationship with, not only the dead, but also the outcasts of society, those left for dead, and of approaching each performance, each movement, as if dying and being reborn: “Today I am no longer a dog. Albeit clumsily, extremely clumsily, I am definitely recovering. What, however, does my recovery signify?...Haven’t I already recovered? Don’t I continue to recover in order to be sick?” (Hijikata 2000:43).

Like a shaman, Hijikata created image-based training methods for working with psycho-physiological connections to animals, nature, and spirits. He developed clearly delineated, ritual-like structures for accessing spirit-like, mind-body states, improvised moment to moment. For example, Natsu Nakajima, one of Hijikata’s first students, states, “Hijikata would tell us: ‘Make the face of an old devil woman, with the right hand in the shape of a horn, and the left hand holding her long hair…then comes the light of the sun, and the eyes become smaller; then comes the wind, and the eyelids quiver; then you must feel like a stone’” (cited in Viala and Masson-Sekine 1988:135).

The initiatory journey to the spirit realm for shaman neophytes is a journey of death. From the incipient moment of their initial affliction, their old self begins to die and walk the path towards a new existential state, a being capable of repeating this journey of their very own death whenever necessary, when called to by nature or society. Likewise, Hijikata called for Butoh dancers to take the same journey, to occupy the stage as a shaman might occupy a ritual drum circle, disappearing within and without his body in a state of crisis seeking resolution:

A person not walking but made to walk…not living but made to live…not dead but made to be dead…Sartre wrote: “A criminal with bound hands now standing on the scaffold is not yet dead. One moment is lacking for death, that moment of life which intensely desires death.” This very condition is the original form of dance and it is my task to create just such a condition on the stage. (Hijikata 2000:46)

Both implicit and explicit in much of the theoretical literature on trance, possession, and shamanism is the idea that music and dance can be performed either mixed/integrated or parallel/unintegrated. Gilbert Rouget, for example, makes a comparison between numerous practices, including Araucan tribal shamans, Candomble neophytes, Tungu apprentices, and Ammasalik Eskimos, just to name a few, pointing out that each of these contains very different degrees of integration between music on the one hand and either dance or ritualized behaviors on the other. The latter may or may not include direct participation in the playing of music or song (Rouget 1985:125-126).

This principle holds true as well for Butoh, as it does for almost any performance medium. However, Butoh performers are also capable of acting in concert with music and music-making in whatever form and to whatever degree the lead artist of a performance wishes them to. Possession ceremonies tend to relegate mediums to a fairly passive, reactive role in relation to music, whereas shamans generally assume an active role as musicants (Rouget 1985:126). Those involved in Butoh, on the other hand, since they are usually artists at least as much as they are trance practitioners, are generally free to ply these musical waters as they see fit according to the performative or ritualized needs of a given dance, performance location, or audience configuration.

Sound, Structure, and Curative Aspects

Within these differences, the use of music in Butoh does have some basic elements in common with traditional ritual forms. One is its ability to structure ritual aspects of a performance event. A seminal example of this is Admiring la Argentina, a full-length solo performance by Kazuo Ohno, the co-founding artist of Butoh with Hijikata.6

Butoh performances typically begin with music or sound at a very low volume or even in silence. Generally speaking, this allows for the performers, who have already begun to sink into a meditative or trance-like state before appearing in front of an audience, to continue to deepen this condition and connect with some personal or societal ill that will inspire the tension and contradiction inherent in their dance.7 Similarly, in speaking of the Bushmen shamanic rituals, Rouget states that there must be music, dance, and serious illness all present for trance to genuinely occur:

One might perhaps take the view that the long preparation provided by the dance, which “warms up” the healer’s power and brings it to a boil, creates an emotional state within him that is equivalent, as far as disturbance of his consciousness is concerned, to that resulting from the critical situation with which he is suddenly faced when he must heal a seriously ill patient. (Rouget 1985:144-145)

In the introductory section of Ohno’s performance, Ohno begins seated in the audience costumed in an ornate dress and large hat, evoking the diva-like persona of a tranvestite male prostitute. Slowly, out of the silence, the sound of Maria Callas singing an aria from Puccini’s Manon Lescaut is heard faintly in the distance. Ohno slowly rises up and makes his way methodically to the stage, where he lays his cape and hat down in preparation for the rest of the first half of the piece, which includes a figurative death and rebirth (as an innocent young girl) to Bach’s iconic Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. Ohno then returns dressed simply in dancer shorts and shoes, covered in white, ashen, ghost-like makeup. He dances in front of a grand piano in a symbolic rebirth as a pure spirit, himself as an energized, spiritualized blank slate, first in silence and then to excerpts from the Well-Tempered Clavier.

In the second half of the show, Ohno returns carrying the spirit of Antonia Merce, known as La Argentina, a Spanish-Argentinian dancer active in the early 20th Century who was the inspiration for the performance. He dances to tango music in a succession of both severe-looking and ornate costumes, overtly blending the mixed-heritage dance influences of both La Argentina (tango and flamenco) as well as his own (pre-World War II German Expressionist and post-war Butoh). The piece ends with Ohno depicting both age and decay (he premiered the work in his early seventies and performed it until his mid-eighties), dressed in a white ruffled gown, as well as youthful innocence and desire, dancing to Puccini’s “O Mio Babbino Caro,” written dramatically from the point of view of a teenage girl but sung on the recording used by Ohno by that most iconic and deep-throated of grown woman sopranos, Maria Callas.

Thus, we see the structure of this performance allowing for an increasingly trance-like state. Ohno’s movements and gestures are heavy, methodical, asymmetrical, and halting, yet somehow graceful and transcendent. The increasingly dramatic but contained music of the first half onstage (Bach) supports his attempt to deepen his communion with the spirits of both the male prostitute and the young girl that emerges from inside the former character. As we then see him dancing in silence in front of the piano and stripped of all costuming but still with the artifice of full-body, ashen makeup, the simultaneous absence and potentiality of the incipient live music-making supports the cyclic, regenerative aspect of the performance that is directly parallel to the symbolic (if not literal) rebirthing elements in shamanic ritual. As the live music is then introduced, first as a single instrument (piano) and then in full, frenetic tango ensemble, Ohno’s dance becomes increasingly disjointed and frenzied as he attempts to reconcile the myriad influences of both the character he is trying to embody (La Argentina) as well as his own real self. The final dual image and sound of Ohno dancing a girl and old woman and Callas singing Puccini’s teenage paean to lust and love rounds off this dramatic cycle that contains, in principle, the basic structural and sound elements of a shamanic journeying ritual.

This last aspect alludes to another commonality between music in Butoh with possession and shamanism, namely the use of music to contextualize affliction and curative ritual elements. This is typically accomplished through a symbiotic relationship between the Butoh artist’s characterization and choreography and the music’s content and structure. Creating characters that are somehow unresolved or schizophrenically-structured (such as Ohno’s dead woman/lustful teen or male prostitute/young girl) manifests a psychic equivalent to the music’s thematic, historical, linguistic, or other context (like Ohno’s use of Italian opera and Argentine tango or German church fugue and silence). Ohno’s dancing in an off-kilter, grotesque, and broken manner in Admiring La Argentina to an alternating, contrapuntal progression of different forms of music structures an experience for the viewer that simultaneously communicates a sense of illness, disintegration, reconstitution, and, ultimately, transcendence.8

Butoh performance is fixated on the destruction and reconstruction of the mind, body, spirit, and identity; on the fact that cells are dying and being born throughout our bodies in every moment. The reality of this constant manifestation of life and death within the overall arc of a lifespan provides essential inspiration. Ohno himself states:

In life there is…something between life and death…like the wreck of an abandoned car; if we fix it, it could start up again…Butoh’s best moment is the moment of extreme weariness when we make a supreme effort to overcome exhaustion. That reminds me of my show in Caracas…My body had grown old and I was working like a rickety old car, but I was happy. Is that what we call wearing oneself out for glory? The dead begin to run. (cited in Viala and Masson-Sekine 1987:36)

Generative and Integrative Aspects

Butoh also allows for the use of music as being existentially creative and generative of states of mind and being itself. In quoting Rousseau, Rouget states that this may occur as simply as a prodding of memory: “’The music then is not acting precisely as music, but as a mnemonic sign’” (Rouget 1985:168). However, as Judith Becker describes when citing research on Thai trance dance, this process of affect may be much deeper and broader than mere emotional recollection:

Music provides a link…by enveloping the trancer in a soundscape that suggests, invokes, or represents other times and distant spaces, the transition out of quotidian time and space comes easier. Imagination becomes experience. One is moved from the mundane to the supra-normal: another realm, another time, with other kinds of knowing. (Becker 2004:27)

In other words, the composition and arrangement of music has the potential to stand in for the actuality of worlds that generate or supplement possession or shamanic states. Becker goes on to explain that another aspect essential to the effectiveness of such a process and the very ability to trance is the requirement of an engaged self in concert with all ritual elements, including music:

To feel oneself at one with the music and the religious narrative enacted there must be no distance at all between event and personhood: no aesthetic distance, no outside perspective, no objectivity, no irony. Later perhaps, the trancer may reflect…but to do so at the moment of trancing is to introduce the very disengaged subject that will break the enchantment. (Becker 2004:92)

In discussing the narrative aspects of Bissu ritual, she describes: “To become possessed by the deities, there must be no ironic distance between bissu selves and the origin myth they enact. Music, story, bissu, and deities become one” (Becker 2004:105).

In other words, music is most effective when integrated with self and narrative, not just parallel. Like a talented actor might do with a play or dialogue, Ohno becomes a present energetic manifestation of both himself and La Argentina when music is played in his performance, especially by the live tango group.

Begging the reader’s indulgence, I would like to cite another example of this process from my own performance work, a contemporary dance and theater piece entitled, “The Crook: A Revival.” The play was structured somewhat along the lines of a ritual, assisted suicide of the theatrical medium itself as a metanarrative commentary about Western narrative conventions and the hegemonic control factors embedded within them. However, having established this ironic distanciation within the overall structure of the work itself, the actors, all of whom were trained during the rehearsal period in Butoh-based performance techniques, were then allowed in actual performances to go as far as they were able to emotionally, physically, and psychically.

The climax of the play takes place in a Revival tent atmosphere with a Jim Jones-like, preacher figure exhorting both the cast and audience to cast off the bounds of their socialized, artificially-separate roles as “actors” and “viewers.” An old American Pentecostal field recording plays, giving this theatrical but reconstituted environment, full of increasingly tense and screaming participants speaking nearly in tongues or nonsense language, an air of authentic experience. Additionally, a sound artist sits to the side of the playing area, amplifying and manipulating both the recorded and live sound of the music and dialogue as a soundscore “played” live and within which the dancers and actors are let loose to try and perform their way out of a black hole-like, energetic and narrative void.9

For the dancers and actors in The Crook, this is akin to what Becker describes as, borrowing a term from Bourdieu, the habitus of listening, wherein “a trancer and the self who is listening are indivisible: one includes the other. The listening self at a spirit possession ceremony is a self who waits and listens for clear signs of intervening holy spirits, signs that he/she is about to become a different self” (Becker 2004:106).

Rouget points out that Bushmen healers participate just enough with the musicians to make the music part of his directly internalized experience and psycho-physiological state but not so much that he cannot fall out of the music-making process deeper into trance as needed while the other musicians keep playing, enabling him to continue “trancing,” regardless of his moment by moment musical role (Rouget 1985:142). In other words, the shaman’s listening self as highlighted by Becker is able to participate directly in music-making while the deeper trance state beyond that level may be supported as necessary by the non-trancing musicians, just as the dancers and actors in The Crook were supported by the non-trancing, soundscore performer.

Trance rituals are often spoken of as having a feeling of extreme slowness, timelessness, or an ability to “stop time.” Butoh artists are also considered, especially to those unfamiliar with actual Butoh-based practice, to generally move very slowly in performance, rehearsal, and workshops. There are many stereotypes that have propogated about every form of performance, and the one most often stated about Butoh is that it occurs in slow motion. However, this is not quite correct. Slow motion is an actual or symbolic alteration of the speed itself of time. In other words, the actual movement underlying slow motion is not as slow as one observes. Instead of altering the speed of time itself, however, Butoh performance reframes real time as is, both actually and symbolically.10 Butoh performers do not move in slow motion so much as they move within a more gradual, methodical, patient, or focused structure of time.

We might apply this idea to trance rituals as well, especially within the context of music. Becker herself cites Rouget in discussing music’s ability to reframe time in this manner and largely determine our experience of time itself: “The slower the processing of mental images becomes, the more removed one feels from the ‘time’ of living bodies progressing from sunrise to sunset in a nonstop succession of activities and mental images. Slowing the mind is…a by-product of trance consciousness as well,” (Becker 2004:133) and “music modifies our consciousness of being… It is an architecture in time. It gives time a density different from its everyday density. It lends it a materiality it does not ordinarily have and that is of another order” (Rouget 1985:121).

In relation to Butoh’s functional ability to achieve and maintain a trance state, Becker’s hypotheses based on Damasio’s theory of core self/core consciousness and autobiographical self/extended consciousness may shed some light. As she describes:“Core consciousness…is the sensation of knowing one’s body-state in relation to a self. Extended consciousness builds upon core consciousness but includes the memory of our bodily interactions with our world and the sense of the continuity of our being throughout our life histories” (Becker 2004:135).

In either mental disease patients, shamans, mediums, or Butoh dancers, a split or divided function may occur between these two sides of the same mind, allowing for temporary replacement of the autobiographical self, the one concretely active on the conscious level in our day to day lives, by another mode of awareness.

Trancers are fully conscious; they respond appropriately to their milieu, moment by moment. But they may not always attribute their trancing experience to their autobiographical selves. The trancing experience may belong to the trance persona and not to the autobiographical self. (Becker 2004:141)

The act of a shaman or possessed medium replacing his or her autobiographical self with a spirit identity, i.e. a temporary trancing self, is comparable to what Butoh performers do via identificatory processes when “becoming one” with a character or other entity. For example, decades ago, Kazuo Ohno developed a dead body container concept for Butoh training, a technique now used by performers worldwide. As Jean Viala describes:

The dancer must separate himself from his physical and social identity. Ono says that Butoh revolves around the idea of the “dead body,” into which the dancer places an emotion, which can then freely express itself. Without this technique, the “living body” would divert the emotion, drawing us into its own logic. (Viala and Masson-Sekine 1988:22)

In terms of the interaction of this temporary self with music in Butoh performance, a symbiotic, ritually functional relationship accretes over a span of time (either the creative/rehearsal period or during the dance itself) between the trancing self that temporarily replaces the autobiographical self and the repeatable music designated to instigate, accompany, and/or maintain the trance state and ritual performance process.

I would like to extend the above ideas into a final theory surrounding the experiential core or Butoh and trance rituals and where they might sit on a greater societal level.

Our ideas of our selves, at root as well as the socialized bodies/selves that we acquire, are considered to be largely resident in preexistent cultural narratives: “Notions of personhood…are imagined as situated within a situation, acting in a particular way, responding verbally and gesturally to specific events and particular people. The imaginary narratives are, in broad outline, already present in the society into which we are born” (Becker 2004:88).

The specific cultural narrative of a Western-oriented, overwhelming rationality that purposely seeps into every facet of active daily being was the one that Hijikata rejected along with text-based processes of social legitimization that valued verbal over non-verbal forms of truth, authenticity, and authority. As discussed above, trancing does not allow for highly verbal interaction with self as verbal activity causes experiential distanciation from self. Becker furthermore notes Damasio’s highlighting of the potential for separation between core consciousness and inner languaging, the latter of which is central to our normative sense of self: “Damasio…believes that inner languaging is a function of extended or biographical consciousness but not of core consciousness. Core consciousness does not need language and needs only the briefest time span of memory” (Becker 2004:145).11

Thus, trancing selves are not considered, in Western normative terms, as legitimate forms of expression or, frankly, being. If they indeed replace the autobiographical self in the mental realm, then they are also replacing the essence of one’s culturally-inscribed and socially-acceptable identity, not just who one normally thinks one is, but perhaps more importantly, who everyone else thinks one is and, therefore, the standard by which one is measured, valued, judged, and used in the social realm. This may lead to an overall effect of trance as social crisis.

This is not, in principle, a new idea. Rouget enumerates many studies of possession, initiation, and therapeutic ritual in which “trance” and “crisis” become nearly identical references (Rouget 1985:39). Trance is a form of crisis in that it represents a break from the normative social order. In this sense, it fits within the crisis phase of Victor Turner’s social drama theory of breach, crisis, redress, and reintegration (Schechner 2006:211). Trance is therefore also a liminal state, not only due to its place in social drama, but also because of its temporary and impermanent form, i.e. the trancing self is temporary and represents a break with the normative bonds of “personhood.”

Butoh practice follows from and through liminality, aiming to release the mind/body from a purely logical structure to achieve a transcendent wholeness. Japanese critic Nario Goda states: “In Hijikata’s Butoh, half of the self is not conceived, so it is very dynamic. It is theatrical because it is alive and unfinished. In this way, the audience can read it freely. Total art is totalizing (totalitarian). We can learn to be happy with what is finished and imperfect” (Horton Fraleigh 1999:176).

Moreover, if each practice purposely engages in schismogenetic cycles, maintaining crisis states in order to keep in touch with their respective realities, then repeatable, curative procedures are essential components of their overall processes as well. These may come in the form of aestheticized sickness and healing cycles, much in the way of what Turner refers to as “rituals of affliction,” wherein there exists:

…a strong element of reflexivity, for through confession, invocation, symbolic reenactment and other means, the group bends back upon itself...not merely cognitively, but with the ardor of its whole being, in order…to remember its basic relationships and moral imperatives, which have become dismembered by internal conflicts. (Turner 1985:233)

In other words, practitioners aspire to maintain their social nature by embodying both poison and cure within their liminal state. As Turner writes, that which is fluid and indeterminate may become integrated and potentialized:

Indeterminacy is…that which is not yet settled, concluded, and known…It is that which terrifies the breach and crisis phases of social drama…Indeterminacy should not be regarded as the absence of social being; it is not negation, emptiness, privation. Rather it is potentiality, the possibility of becoming. (Turner 1982:77)

As shamanic and possession rituals typically involve initial and initiatory phases of affliction as well as often being propitiatory to appease ancestor and controlling spirits, trance rituals are also typically rituals of affliction. They are also inherently recursive against hegemonic order. They take their delegitimized, i.e. afflicted, states and embody both poison and cure with the result of self-inscription and empowerment.

Further, such liminal states and rituals also lead to what Turner labels communitas, i.e. a communal liminal state that, due to the benevolent potentiality of liminality, is capable of producing a heightened sense of comradeship, togetherness, and shared experience or purpose. Thus, just as Butoh was designed as a social oppositional strategy, so shamanic and possession ritual can act as or represent a manifestation of cultural or national identity (Racy 2008). In the midst of ritual and performance forms structured around music, dance, and embodiment of the ineffable and dedicated to recursive forms of mind/body/spirit healing and reintegration, the broader nature of a group’s humanity or even social status may intuitively take hold: “A trance/music event is not just in the minds of the participants, it is in their bodies; like a language accent, trancing and playing music are personally manifested but exist supra-individually…the event as a whole plays itself out in a supra-individual domain” (Becker 2004:129).

Such a domain may take the form of a social structure out of the past that a social group’s participants treat as a qualitative reflection on the present. This is the case, for example, in Northern Thailand, where spirit mediums participating in faun pii, communal spirit dance ceremonies that take place every year in the weeks leading up to Buddhist Lent, are possessed by and embody local historical figures from centuries past. These may include former royalty, military conquerors, and folk heroes that “return” to the present, dispensing wisdom from beyond the corporeal realm and simultaneously paying tribute to themselves within the physical world in a public display of nostalgia for a pre-colonial and pre-modern era, before the subjugation of Northern Thai, post-feudal, city-states to a centralized Siamese government in cooperation with British logging and agricultural concessions (Morris 2000).12

Spirit mediums at Faun Pii ancestor worship ritual, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2008.

As examined above, shamanic journeying, possession, and Butoh all sit at an existential nexus of social affliction, psychic energy, and desire for resolution in mind, body, and spirit. Moreover, while all three categories utilize music-based, ritual practices to embody corporeal, energetic, or spiritual entities, each does so in different levels of status as musicants, with Butoh artists as the most variable and in a way that allows them to take on a wide range of presence and expression. Finally, these forms of social performance in their own way possess a transformative knowledge gained from literal or figurative life and death experience and the will to transcend darkness into light based on a fundamentally benevolent worldview that attempts to provide some form of hope or at least inspiration to their participants and audiences.

1. For the purposes of this article, I employ my own generalized definition of Butoh based on the writings and practices of numerous first and second-generation artists, most notably, Tatsumi Hijikata, Kazuo Ohno, Yoko Ashikawa, Akaji Maro, Min Tanaka, and Ushio Amagatsu and writers such as Nario Goda and Yukio Mishima. It should also be noted that there is very little agreement whatsoever on a definition of Butoh within the Butoh community itself.

2. For the most in-depth, English-language texts, I refer the reader to Viala and Masson-Sekine (1987), Klein (1988), Kurihara (1996), and Ohno and Ohno (2004).

3. The extent to which various notions of “Japaneseness” affected the creation of Butoh as well as its subsequent practice within and without Japan remains a worthwhile topic outside the focus of this article, which concentrates instead on theorizing more universal aspects of the form after nearly 50 years in existence and, at this point, practiced by artists on every continent.

4. While Eliade has received a great deal of criticism in relation to his fundamental use of archetypes for vast theoretical claims, a general lack of first-hand fieldwork, and somewhat authoritarian socio-political tendencies, my use of his ideas here are focused on his collection and basic analysis of a great deal of fieldwork observations from around the world and over many decades.

5. Field research on Northern Thai spirit mediums, Chiang Mai and Lampang Provinces, Thailand, 2008-09.

6. This description and analysis of Admiring La Argentina is based on published descriptions of the piece, Ohno’s own recollections (Hoffman and Holborn 1987; Viala and Masson-Sekine 1988; Ohno and Ohno 2004), as well as my own viewing of the performance live in Los Angeles in 1993.

7. Without requiring one’s self to perform on this sort of “knife edge” of contradictory impulses between socialized and acculturated habits and root, intuitive actions, the performance is generally not considered as authentic and, therefore, not Butoh.

8. This sense of ultimate spiritual transcendence in Ohno’s work may or may not relate directly to shamanic or possession ritual so much as to Ohno’s own religious belief and practice as a devout Christian.

9. “The Crook: A Revival,” workshop version at Los Angeles Theatre Center, July 2005, and premiered at Track 16 Gallery, Santa Monica, CA in April-May, 2006. Co-written and co-directed with Rochelle Fabb. Music and soundscore by Bob Bellerue. Reviews in the Los Angeles Times, LA Weekly, and Socal.Com.

10. An analogy may be that windows of different shape and size looking out onto the same landscape do not inherently change or alter the latter but rather the perspective on and experience of it.

11. A simple illustration of this phenomenon might be the visceral difference between a spontaneous memory instigated in the moment by an external factor as opposed to the premeditative act of remembering (re-member-ing, i.e. the conscious act of putting something(s) back together) something.

12. This research is from a conference paper entitled “Ladyboys and Good Sons: Contemporary Gender Identity in Northern Thai Trance Dance” presented at Cornell University Southeast Asian Studies Conference on October 25 in Ithaca, NY.

Becker, Judith. 2004. Deep Listeners: Music, Emotion, and Trancing. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Eliade, Mircea. 1964. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstacy, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Hijikata, Tatsumi 1993. Hijikata Tatsumi: Three Decades of Butoh Experiment. Tokyo:

Hijikata Tatsumi Memorial Archive, Asbestos-Kan.

_____. 2000. “Inner Material/Material.” The Drama Review 44(3):36-42.

_____. 2000. “To Prison.” The Drama Review 44(3):43-48.

_____. 2000. “Wind Daruma.” The Drama Review 44(3):71-79.

Hoffman, Ethan and Holborn, Mark. 1987. Butoh: Dance of the Dark Soul. New York: Aperture.

Horton-Fraleigh, Sondra. 1999. Dancing into Darkness: Butoh, Zen, and Japan.

Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Kirby, E.T. 1976. “The Shamanistic Origins of Popular Entertainment,” in Ritual, Play, and Performance, edited by Richard Schechner and Mady Schuman, 139-149. New York, NY: The Seabury Press.

Morris, Rosalind C. 2000. In the Place of Origins: Modernity and Its Mediums in

Northern Thailand. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ohno, Kazuo, and Ohno, Yoshito. 2004. Kazuo Ohno’s World from Without and Within. Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.

Racy, A. J. 2008. Class lecture, Ethnomusicology 267: Music and Ecstacy, October 7, Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Ethnomusicology.

Rouget, Gilbert. 1985. Music and Trance. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Schechner, Richard. 2006. Performance Theory. New York: Routledge.

Turner, Victor W. 1982. From Ritual to Theater: The Human Seriousness of Play. New York: PAJ Publications.

_____. 1985. On the Edge of the Bush: Anthropology as Experience. Edited by Edith L. B. Turner. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press.

Viala, Jean and Masson-Sekine, Nourit. 1988. Butoh: Shades of Darkness. Tokyo: Shufunotomo Co., Ltd.