As It Was In The Beginning, Is Now, and Ever Shall Be?: Church Organists, Community, and Musical Continuity

Biography

Deborah Justice is an ethnomusicologist, hammered dulcimer player, and old-time guitarist. She has presented her research at conferences for the Mid-Western and Middle Atlantic Chapters of the Society for Ethnomusicology and has been published in Journal of Folklore Research Reviews and Dirty Linen. Her research interests include music and religion, American roots music, and musics of the Middle East. Ms. Justice is currently conducting research on mainline Protestant music in the United States, with a focus on music as a manifestation of social reconfiguration. She holds a Master’s degree from Wesleyan University and is currently a doctoral candidate at Indiana University.

Abstract

Do local church organists form communities? As ritual specialists, church organists have long played an indispensible role in facilitating North American and European Christian worship. Despite the diverse musical practices of Christianity, most mainline Protestant Sunday morning organ music falls within a relatively narrow range of repertoire and performance practice. Such musical continuity implies a level of communication between organists. Yet, since most organists work similar hours on Sunday mornings, they only infrequently observe each other during services. What explains the musical similarities? Do organists share educational backgrounds and sources of repertoire? How does musical information travel between organists? How does the contemporary reconfiguration of mainline Christianity impact organists’ sense of community? In this paper, I explore these issues through one basic question: do local organists form a musical community?

A shared profession often provides a touch point for community. Such a community may be as informal as coworkers bonding over a coffee break, or it may take more organized forms. Workers in the same field create vocationally-focused communities through unions, guilds, and professional societies. They also often form socially-focused communities through volunteer groups, sports teams, and happy hour outings. Musicians who perform similar genres also tend to form types of communities. From Irish pub sessions and local bluegrass jams to the slate of BMI artists and symphony orchestras, musicians create communities based on a variety of interconnected reasons including shared musical aesthetics, social enjoyment, and professional concerns.

Proceeding from the assumption that community rests on communication, church organists offer a particularly valuable instance for the study of musical communities.

"Love Divine, All Loves Excelling"

Performed at Hillsboro Presbyterian Second Service, July 13, 2008.

Few small and medium sized churches hire more than one organist, and this individual is often visually obscured by a large console or hidden away in a choir loft or balcony. Nonetheless, the former Dean of Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music echoes an opinion commonly held by many Christians: organists “are completely necessary,” (Webb 2006). Many Western Christian traditions have long relied on church organists to provide the sonic threads that weave together ceremonial elements of worship (Etherington 1962). As ritual specialists, organists use music to propel ritual actions of communal worship. For example, on Sunday mornings across the United States, organists signal a shift from congregational thanksgiving to praising by transitioning from the Offertory music into the Doxology; they bring a well-trained congregation to its feet simply by sounding the opening notes of the Gloria Patri. Throughout mainline Protestantism, organists perform similar functions and similar repertoire.1 Indeed, the traditional predominance of the pipe organ in mainline Protestantism’s “joyful noise unto the Lord” stands as one of the strongest points of ecumenical common practice between these various denominations.

Such high levels of similarity suggest equally high levels of communication and community. Yet, church organists work in relative professional isolation. Many towns have multiple church organists, but very few churches support more than one organist. Since church organists work overlapping Sunday-morning hours, they are not often able hear each other play for services. Nevertheless, the similarities between their professional responsibilities, repertoires, and musical aesthetics remain. Do organists form communities despite their inherent Sunday-morning isolation? If so, which forms do such communities take?

These questions of community take on new significance when considering organists as ritual specialists within the current reconfiguration of American religious practice.2 American and Western European churches find that organized religion has increasingly become an optional, affinity-based activity. Previously, churches could rely to a greater extent upon people’s sense of civic and religious duty, social pressures, and geographic proximity to fill their pews (Wind and Lewis 1994). However, the current religious landscape is much more consumer-driven, with church-goers selectively “church shopping” for a congregation that offers their ideal blend of worship and social elements. Many evangelical churches, non-denominational megachurches, and mainline Protestant denominations use music as a primary way to attract and retain parishioners.3 In keeping with their centuries-long historical and cultural traditions, mainline Protestants have been comparatively slower than Evangelicals and megachurches to incorporate popular media, musical styles, and instrumentation (Turner 2008:6).4 Controversy over Sunday-morning musical styles grew so heated during the 1990s that the disagreements were dubbed “the worship wars.” Nonetheless, steadily declining mainline membership roles – in comparison with Evangelical and megachurch growth – have convinced many mainline churches to literally change their tunes. Mainline Protestants have been slowly, but surely, diversifying their offerings of pipe organs, choirs, and hymnody to incorporate multiple musical genres.

In growing numbers of mainline Protestant congregations, organ-based worship has gone from being thestyle of service to one of many styles. Musical ritual specialists continue to play a central role in mainline Protestant religious practice, but these musicians are no longer necessarily organists. Organ players may have been “completely necessary” in many mainline Protestant churches, but their indispensability only extends to “traditional” worship today.5 For many Christians in Europe and North America, guitar-driven “contemporary” worship has become a viable alternative to organ-based “traditional” worship.

Organists, Community, and Change

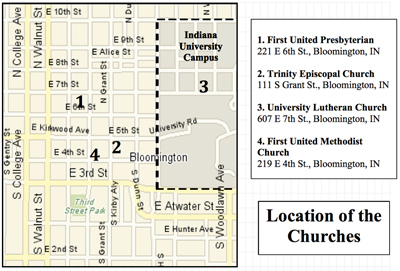

“The ethnomusicologist, by thinking about the musician first, can easily make a significant contribution to any given area of ethnography, history, or sociology that has ignored the performer” (Slobin 1989: xvi-xvii). Much scholarship on American Christianity addresses the worship wars, “traditional” versus “contemporary” genres, and overarching social, cultural, and theological issues. Analyzing individual organists provides a unique point of entry into the everyday embodiment of American religious reconfiguration. The following brief analysis of four organists based in Bloomington: Lidetta Matthen, Chris Wilson, Marilyn Keiser, and Charles Webb, opens doors to further exploration of many complex issues, including networks of musical distribution, methods of musical transmission, pedagogical systems, the impact of childhood musical exposure, genre, codification, aesthetics, and truth claims of inherent religious value in certain musical genres. In this article, however, these broader issues remain as substructure informing the more concrete questions posed to the organists. During this period of musical diversification organists, through mainline Protestantism, render comparatively similar “traditional” worship services each Sunday. How do they come to understand and share the values of this musical genre? To what extent do these relatively professionally-isolated ritual specialists communicate and commune with each other? In short, do they form communities? I address these questions through comparative ethnography of four organists serving mainline Protestant churches adjacent to Indiana University – Bloomington.

At the time of my research, the four churches closest to the western edge of campus were mainline Protestant churches. These four churches employed organists of varying backgrounds: one Indiana University graduate without continued ties to the university; the former dean of the School of Music; the current head of the Indiana University organ program; and an Indiana University mathematics graduate student.6 In the following section, I offer brief biographical sketches of each organist that illustrates many of the abovementioned musical, cultural, and social issues. I then build upon this descriptive foundation with analysis of the organists’ perceptions of and attitudes towards the notion of an organ community in Bloomington, Indiana.

Lidetta Matthen, Organist and Choirmaster, First United Presbyterian Church

Lidetta Matthen came to her position as the organist and choir master at First Presbyterian Church following a combination of informal and institutionalized musical training. Matthen was raised in a family that attended church on a regular basis. Like her two sisters, she began to play piano around the age of eight. Her parents encouraged her, particularly her father who had studied violin at the Cincinnati Conservatory. When she turned eleven, Matthen began to play piano for children’s Sunday School classes at her church. Three years later, when the family moved to Richmond, Virginia, Matthen began to sing in the choir and play for the children’s Sunday School classes in her family’s new Baptist church. Upon the urging of her family and new friends, she attended a church camp class on music ministry. The experience opened a door for Matthen, revealing a musical path that she had never considered.

The following year, Matthen’s growing interest in sacred music intensified when her church purchased an organ. She had previously been fascinated by her maternal grandmother’s small pump organ. The full-size version proved even more captivating. “Every day,” she recalls, “I would take the bus from school to church to practice organ” (Matthen 2006). Matthen found a helpful role model in her choir director, who soon became her organ teacher.

Matthen’s first paid organ position came when a local Episcopalian church from across town called her in desperate need of an organist. Following many more temporary positions, she decided to pursue a career in sacred music. She explains, “I loved people, and I loved music. I found my place, my nitch” (ibid). Matthen designed her formal education to further her goal of becoming a church musician. Due to strong family ties to Westhampton College at University of Richmond, Matthen chose to study music there. Despite the school’s lack of an organ, she graduated with her bachelor’s degree in music, a concentration in piano, and “a cracking good education” (ibid.).7

Her pianistic skill and studies notwithstanding, Matthen realized that organ would provide her more steady employment. She clarifies, “I needed to be able to make a living, so I’d rather be a church organist” (ibid.). Matthen enrolled in Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music where she received her Master’s concentration in organ after an accelerated year of concentrated coursework and recitals. Supplementing her university studies, Matthen received practical training by assisting Ozzie Regatz, the organist at First United Presbyterian Church in Bloomington. In 1973, Regatz retired and Matthen became the full-time organist and choir master at First Presbyterian Church. In addition to her primary position at First Presbyterian Church, Matthen also taught keyboard classes for twenty-eight years at Indiana State University.

What began for Matthen as informal tutorials with a small town organist progressed to study at a prestigious music school and finally to professional employment. Matthen’s combination of classroom instruction, practical training, and personal experience in worshipping with a variety of Christian denominations prepared her for work in a mid-sized church. Her current position at First Presbyterian covers a wide range of interrelated functions. Officially, First Presbyterian has no music minister, but Matthen covers most of the duties traditionally held by someone in such a position. She holds responsibility for directing the choir and for coordinating the music in the service: preludes, postludes, anthems, calls to worship, introits, and responses. The pastor selects the hymns, but often consults Matthen for advice or suggestions. She participates in rendering almost all of the music on piano or organ. In sum, Matthen strongly influences the repertoire and aesthetic flow of the entire service.

Chris Wilson, Organist, University Lutheran Church

Chris Wilson came to his position as the organist of University Lutheran Church largely through informal organ training. Similarly to Matthen, Chris Wilson traces his interest in the instrument to childhood. Raised in a family that attended church regularly, he worshiped with organ music most Sunday mornings. Matthen has additional family connections to the organ as well; both his maternal and paternal grandmothers were church organists.

Wilson began to play the organ in junior high school. Having taken piano lessons throughout elementary school, he was already familiar with one keyboard instrument. Prior to taking the occasional lesson with his church’s organist, Wilson practiced on his own with the church’s instrument. Although he did not have much guidance, his playing skill improved. He became accomplished enough through these informal methods that he was asked to substitute for his church’s organist on occasion. By high school, Wilson had improved enough to take on his first paying organ job, playing part-time for a neighboring Catholic congregation.

Although Wilson pursued formal musical education, organ continued to be a secondary interest for him. He earned his bachelor’s degree in music education with a concentration in piano, but he had still taken only “a smattering” of organ lessons (Wilson 2006). During these occasional sessions, he learned mostly from a few local South Bend, Indiana, organists. He notes that the organist at Faith Lutheran Church, Indiana University graduate Julie Grindell, was particularly influential on his playing.

Wilson moved to Bloomington, Indiana, for graduate study. However, he chose to pursue higher education in mathematics rather than in music. Nevertheless, continuing his informal organ training, Wilson has availed himself of the university’s organ opportunities. He has attended some functions of the university chapter of the American Guild of Organists (AGO) and has taken occasional improvisation classes with the organ-department-chair, Dr. Marilyn Keiser.

Wilson began worshipping at University Lutheran when he moved to Bloomington. For five years, he occasionally substituted on organ when the church’s regular organist was unavailable. When he learned that the church’s regular organist would soon be leaving, Wilson promptly applied, and was accepted, for the position.

Despite Wilson’s lack of formal organ instruction or institutionalized training in liturgical music, he has become responsible for almost all of the music performed at University Lutheran Church. Similar to Matthen’s position with First Presbyterian that combines organ playing and choral direction, Wilson’s duties include leading and maintaining University Lutheran’s choir.8 Between selecting choir repertoire and organ selections, Wilson is responsible for planning nearly all of the music in the service. He picks the hymns for the service in consultation with the pastor, but these selections are somewhat limited as they base their choices on the lectionary.9 “Some parts [of the service] are fixed,” he says,” like the liturgy. But everything else [is up to me]” (Wilson 2006). Through years of informal organ training and church attendance, Wilson has garnered the experience to successfully fulfill his duties as University Lutheran’s organist.

Marilyn Keiser, Director of Music, Trinity Episcopal Church

Marilyn Keiser pursued a course of formal organ education on her way to becoming the organist at Trinity Episcopal Church. Similarly to Matthen and Wilson, Keiser was first exposed to the piano, but soon switched her focus to the organ. She began taking piano lessons when she was four years old, but by age eight, she announced to her parents that she wanted to be an organist. Her father, a minister, encouraged her. By the age of twelve, she was taking lessons on her uncle’s Hammond organ. Four years later, her aunt arranged pipe organ lessons for Keiser with a local Methodist organist. This “excellent teacher” (Keiser 2006) and Union Theological Seminary graduate gave Keiser a firm grounding in pipe organ. While continuing these formal lessons, Keiser began to play for her own church’s Sunday morning services.

Like Matthen, Keiser pursued a higher education in sacred music and organ. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Sacred Music from Illinois Wesleyan University in 1963, a master’s degree in Sacred Music from Union Theological Seminary in 1965, and a doctorate in Sacred Music from Union Theological Seminary in 1977. This formal training built on her personal history of church attendance and childhood organ lessons.

Following her own education, Keiser pursued positions that combined teaching and playing organ. She served as choirmaster and associate organist at Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York; organist/choirmaster at All Souls Parish in Asheville, North Carolina, and taught on the faculty at University of North Carolina at Asheville and at Brevard College. While in North Carolina, she was hired by the Episcopal diocese to study musical learning in small parishes, which resulted in the publication of her 1986 book, “Teaching Music in Small Churches.”

In keeping with this pattern of teaching and playing, Keiser works in Bloomington as both an organist and a professor. Keiser is currently the Chancellor's Professor of Music in the Organ Department of the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University. She has also been Director of Music at Trinity Episcopal Church for twenty years, playing organ for two services nearly every Sunday. She combines these facets of her life by mentoring an Indiana University organ student at Trinity.

Keiser holds most of the responsibility for music at Trinity Episcopal. She collaborates with the minister and intern primarily in choosing hymns. Keiser selects the special music, preludes, and postludes herself. Like Matthen and Wilson, she also directs the choir and recruits singers and instrumentalists. Keiser’s position at Trinity Episcopal allows her to enact, and hone, the discipline that she teaches at the university.

Charles Webb, Organist, First United Methodist Church

In contrast to the organists previously discussed, First United Methodist’s Charles Webb has maintained an equal focus on both piano and organ. Formal musical education has constituted the core of his training. Webb’s parents were not musicians, but the family attended church regularly. His mother was so impressed to hear him picking out Sunday school tunes on the piano by ear at age four that she quickly arranged for high-quality lessons. Between the ages of eight and twenty-two, Webb studied piano with Paul Van Katwijk, the Dean of Music at Southern Methodist University and conductor of the Dallas Symphony.

Webb’s familial connections continued to facilitate his keyboard studies. While learning piano, Webb became interested in playing organ. His family did not have an organ in their Dallas home, but his church’s organist allowed him to work with the church’s instrument after the Sunday morning postlude. Around this time, Webb’s next-door-neighbor, the conductor of the First Methodist Church in Dallas, introduced him to that congregation’s renowned organist. The woman took Webb on as an apprentice of sorts, taking him to rehearsals and services as a learning experience. Like many organists, Webb found his entrée into church service by substituting for one Sunday service. He was soon called upon to be the weekly Sunday morning organist. Word of his considerable skill spread, and he left this first position when another Methodist church with a higher quality organ offered him regular employment.

Webb’s formal education, however, focused on his career as a pianist. Webb claims that although most people who play both piano and organ prefer one instrument over the other, he has always liked both instruments equally. He completed a bachelor’s degree in English and a master of music degree in piano from Southern Methodist University. Webb went on to earn his doctorate in piano from Indiana University. He was appointed Assistant Dean of the School of Music in the same year and continued there until retiring as the Dean of the School of Music in 1997.

Like Keiser, Webb has sustained regular Sunday morning organ playing in conjunction with his academic work. In 1959, he took a position as choir director at First United Methodist in Bloomington as the choir conductor. However, he explains that when he and the man then serving as organist “closely evaluated their spiritual gifts,” they switched positions. Webb has served as organist at First United Methodist for the forty-eight years since. He describes his organ playing as “a constant musical discovery and a contribution to the service” that he gladly offers as “a devoted church person” (ibid). That First United Methodist has “a wonderful instrument and they keep it up well” is also not unimportant to the professional keyboardist. In addition to playing two services most Sunday mornings at First United Methodist, Webb actively tours as a concert pianist.

Webb’s position at First United Methodist situates him within a clearly delineated system of delegated musical responsibilities. Three staff members—the director of chancel choir, the organist, and the youth choir conductor—work in conjunction with the minister to plan services. Webb selects the hymns, prelude, and postlude, while the choir director selects the choral anthem and any additional music. Webb’s relatively confined position in terms of agency in structuring the service contrasts with that of the other Bloomington organists. Nonetheless, Webb describes this system positively. He reports, “It’s a combined effort, really. In the Methodist Church, the minister is in charge, but we all have a good working relationship” (Webb 2006).

Each of the four organists came to the instrument from similar musical backgrounds and their families played significant roles in bringing the future organists to the organ. Through regular Sunday morning church attendance, the families exposed the young children to organ music. When the would-be organists expressed initial interest in learning the instrument, their families encouraged and nurtured that interest. All of the organists went on to study music on the university level, with three of the four pursuing keyboard training on the doctoral level. They have all worked for churches in a variety of mainline Protestant denominations, as well as occasional work in Catholic churches. Although they are passionate about playing organ, working Sunday-morning services only affords them part-time employment. While their professional duties and responsibilities vary slightly, they fulfill similar expectations: to select and perform pieces of previously-composed “traditional” sacred music.

In many music cultures, such similarities in background, musical duties, and geographic proximity combine with appreciation of musical performance to form musicians’ professional and social communities. Yet, Bloomington’s organists, like so many of their organ-playing colleagues, rarely get to hear each other play as they are simultaneously working on Sunday mornings. Given this inherent relative isolation of individual organists in their own churches, do the Bloomington organists form a community? How do organists describe their relations and communications with their musical peers? How do they maintain the complimentary repertoire and musical aesthetics to fulfill their token roles as “traditional” organists?

To explore these questions, I asked Matthen, Wilson, Keiser, and Webb if they felt as though they were part of an organ community in Bloomington.

Wilson: “There is an IU organ community…, but there are definitely others. And IU organists play in other towns, too—Bedford, Columbus” (2006).

Matthen: “Well, there’s the AGO, The American Guild of Organists. They are over at IU…” (italics added to reflect vocal emphasis, 2006).

Keiser: “No! <pauses> Um, well, there is the AGO” (2006).

Webb: “Hmm. Well, I suppose that depends on how you define ‘community.’ There are many organists. It would depend on if you meant people actually seeing each other frequently, knowing each other talking about organs, being social, etc… I try to converse with other organists, to talk to the organ faculty here at IU, and organists from other churches occasionally” (2006).

Webb’s reply—that the answer depends upon the meaning of the question—accounts for the varying responses. The existence of an organ community in Bloomington rests very much in the experience and expectations of the beholder. While the four organists who I interviewed claimed not to know every organist in Bloomington, they did all reference each other. Given that the interviewed organists work within a half-mile of each other and have served in their respective positions for an average of twenty-six years, one could reasonably expect this these organists to have a degree of knowledge about each other. Yet, Keiser, for example, commented that although organists in other communities go out to lunch as a group periodically, this social collegiality did not happen in Bloomington (2006).10 Knowing of each other creates one form of community, but it does not constitute a reciprocal, interactive community.

Organized Community: The American Guild of Organists

All four organists mentioned the American Guild of Organists (AGO) as one of their first responses to the question of an organ community in Bloomington. Historically, unions and guilds have long facilitated social and professional communities. As a nationally organized, locally embodied group for organists, the AGO would seem to be a likely potential source for fostering an organ community in Bloomington. However, while the organists were unanimous in referencing the AGO, they had varying positions in relation to the organization.

Since its foundation in 1896, the AGO has grown considerably, with a current membership of twenty-thousand members in 348 chapters throughout the United States, Europe, South Korea and Argentina. The AGO is a primarily professional and secondarily social organization. As an educational and service association the Guild, “seeks to set and maintain high musical standards and to promote understanding and appreciation of all aspects of organ and choral music” (“Official Documents” 2006). By emphasizing codification and evaluation—and doing so through particular repertoire—the AGO positions organists within an empirically-valued musical hierarchy that gives deference to sacred European classical music performed on the pipe organ. The AGO website describes the group’s purposes as following:

i. To advance the cause of organ and choral music, to increase their contributions to aesthetic and religious experiences, and to promote their understanding, appreciation, and enjoyment.

ii. To improve the proficiency of organists and choral conductors.

iii. To evaluate, by examination, attainments in organ playing, choral techniques, conducting, and the theory and general knowledge of music, and to grant certificates to those who pass such examinations at specified levels of attainment.

iv. To provide members with opportunities to meet for discussion of professional topics, and to pursue such other activities as contribute to the fulfillment of the purposes of the Guild (ibid).

In pursuit of these goals, the AGO provides a variety of ways for organists to interact with each other. The central organization sponsors local and national professional conferences, while individual chapters often bring guest artists for master classes or brief residencies. In another forum of face-to-face interaction, the AGO holds competitions for young organists and improvisers. On an even more serious level of skill evaluation, the AGO offers variety of multi-level proficiency examinations covering a range of liturgical and performance subject areas.

The national AGO publishes a variety of materials that provide its members with a communal forum to abreast of current trends in organ music and worship. The most widely-read of their periodicals is the monthly magazine, The American Organist. The AGO claims their magazine as “the most widely read journal devoted to organ and choral music in the world” (“The American Organist Magazine” 2006).

This statement and the magazine’s circulation figures help to position the AGO relation to working church organists. The American Organist has a circulation of 23,000 which includes “all members of the American Guild of Organists, the Royal Canadian College of Organists, music schools, libraries, and related arts organizations” (“Advertising Rates” 2006). As these numbers demonstrate, the AGO plays an important role in the North American organ scene. However, while 23,000 subscribers is indeed a substantial figure, there are far more actively-employed church organists in North America. Within American mainline Protestant denominations alone there are 75,800 congregations. Exact figures on the percentage of mainline Protestant congregations that use organs do not exist, but 63% of congregations surveyed in the 2001 U.S. Congregational Life Survey reported using an organ in worship (“U.S. Congregations” 2009). Admittedly, projecting this percentage to claim that 47,800 mainline congregations employ organists would be inexact. This resultant figure would also only speak to organ use within mainline Protestantism, which is just in a fraction of Christian denominations and other religions that use organs. Nonetheless, such projections taken with a grain of salt demonstrate the concurrent significance and limited influence of the AGO.

While the above describes the AGO largely from the group’s own materials, individual organists have varied responses to the realistic enacting of the organization’s ideals. The Bloomington organists speak about the AGO primarily in relation to its local Bloomington chapter. None of the four organists report their local AGO branch as significantly contributing to their experience of a local organ community. Rather, their comments reveal that a divide between university music school students and local town organists strongly impacts the Bloomington organ scene. The Bloomington chapter of the AGO is based in the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University. Even though many of the Jacobs School of Music organ students work part-time in local churches, the students’ social and professional needs drive the Bloomington AGO chapter far more strongly than do the concerns of the students’ more mature local organ peers.

Each of the four organists interviewed had a different response to the AGO as a form of organ community.

Matthen: (Matthen used an upbeat tone of voice when initially describing the AGO).

Well, there is the American Guild of Organists, the AGO, although it’s really organists and choir directors. There are student chapters. You have to pay dues, but there is a spousal discount. They have monthly meetings, take trips to look at new instruments. They sometimes do “organ crawls,” <chuckles> where you get to go inside the instrument to see the pipes. There are also social events, talking about common problems, etc. And they publish a professional magazine, “The American Organist.” And there is an annual meeting of AGO held somewhere in the US for three or four days. (2006)

However, when I asked her if she was an active member of the organization, her tone changed. “I haven’t been to one in a long time,” she says (ibid.). Matthen cites a number of reasons for not keeping up a current membership in the AGO, citing a number of reasons: insufficient notice of meetings, inconsistent meetings and communications, and meeting content. “Most of the members there are students [in the music school at Indiana University],” she explains. “I doubt that many local organists go, unless they are related to IU somehow” (ibid.). While she describes members of the local AGO with whom she interacted as being very friendly, the organization does not meet Matthen’s professional or social needs.

Wilson: As an Indiana University graduate student, Wilson would seem to have potentially strong ties to the many student members of the Bloomington AGO. However, while Wilson is both an Indiana University graduate student and an organist, his graduate work is in the mathematics department. He describes the AGO as:

mostly students in the music school, but some other people, although they are mostly former students. They usually meet once or twice a month. They have choral and organ programs, like the last one on French Catholic Romantic music. And sometimes we will all travel for a show, or they’ll have a concert in honor of something, or hold master classes. The organ faculty is quite active in it, especially in terms of the workshops. (2006)

Wilson tends to enjoy his interactions with the Bloomington chapter of the AGO, although he reports that the group might inadvertently seem somewhat closed to non-university people. “The group just isn’t so connected to the older generation, even when they might take advantage of a mentoring opportunity,” he explains (ibid).

Webb: Like Matthen, Webb does not maintain a current involvement with the Bloomington AGO. While he mentions them promptly when asked about an organ community in Bloomington, his feelings about the group range from generally positive to ambivalent.

The AGO in Bloomington is primarily students working on their degrees, most of them working in regional or local churches. Because of my own busyness, I don’t go to meetings. I’m not sure how they interact with local organists—I would say ‘well,’ but the current organ faculty could address that better. (Webb 2006)

Having retired from his position as Dean of the Jacobs School of Music, Webb has moved outside of the Indiana University organ scene. His description of the AGO positions it securely within that social and professional scene.

Keiser: As both the faculty advisor to the Blooming chapter of the AGO and an active local church organist, Keiser is uniquely positioned to comment upon the organization as a whole. The very fact that the Bloomington AGO chapter has a faculty advisor conveys information about its composition and function. Keiser reports that when group has its monthly meetings an average of twenty people attend. Of those twenty, eighteen are typically students. Keiser is aware of the group’s imbalance remarking that, “We would like more town organists, for their experience and to give the students a chance to interact with the real world” (2006). She is quick to describe numerous social functions of the Bloomington AGO: a fall picnic, spring picnic, socials, and a Christmas party. But, Keiser insists, the organization’s main role is to provide resources for members by sponsoring recitals and bringing in outside experts for workshops and master classes.

Thus, while the Bloomington AGO forms an organ community for Indiana University organ students, the organization does not play as central a role in forming a community for many local organists. The Bloomington AGO is an example of a structured affinity organization (Slobin 1993:56), run as a subsidiary of a national group. Members pay dues for the privilege of their organized interaction with other members and for the opportunity to attend professional development events. As a national organization, the AGO is structured with a general focus on professional development and advancing “the organ.” However, branch chapters interpret these goals in service of local members’ needs. In having such localized focus, the AGO demonstrates that specific group dynamics and social demographics may eclipse general shared interest in the instrument in relation to organ community formation.

If the Bloomington organists do not rely on organized professional associations for community, do they experience community through other forms? The interviewed organists may not come together for regular, organized meetings, but they do report mediated encounters with other organists as creating forms of community. Live concerts, recorded music, and printed materials provide organists with forums of communication. Attending live concerts and organ events provides a face-to-face encounter with other organists, as well as supporting “the organ” as an instrument and institution. While the interviewed organists did not describe the AGO’s American Organist as a primary source of information, they do use other periodical literature, organ recordings, and publishing house mailings to participate in mass mediated organist interactions.

Community through Publications

Matthen, Keiser, and Wilson report that publications from major sacred music publishing houses and from their own religious denominations influence their choice of repertoire. Sacred music publishing houses periodically send organists catalogs with their company’s latest offerings. These may be new pieces, new settings of old compositions, or classic repertoire revisited. While such publishing houses may have ties to a specific denomination, economic viability dictates that their music have ecumenical appeal. Complimenting these publications, all of the mainline Protestant denominations offer musical resources tailored to their congregations’ needs. This music often has considerable over-lap with materials from sacred publishing houses, in fact, much of it originates there. Significantly, however, in contrast to the sacred publishing houses’ purposefully ecumenical, mass-market appeal, music promoted by denominational offices is generally expected to support more specific theological and cultural systems.

Each of the three interviewed organists who report using published materials related to these resources slightly differently.

Matthen: Well-versed in established organ repertoire, Matthen also likes to incorporate new pieces and settings into her playing. Matthen selects her music based on “a lifetime of having done a lot of things and knowing where to look” (Matthen 2006). As such, musical publications form one of Matthen’s most important sources of interaction with the broader community of organists. Her preferred major sacred publishing houses, such as Augsburg Fortress, regularly send her catalogs of their new musical publications.12 While many of these publishing houses represent specific denominations, their materials rarely reflect prohibitively particular theological differences between mainline Protestant denominations. Designed to appeal to relatively broad ecumenical use in worship, these publications reflect a generalized mainline Protestant theology and an equally nonspecific Western classical musical aesthetic. Matthen considers these catalogs’ selections and frequently orders new music from them for use in Sunday services.

In addition to publishing house catalogs, Matthen uses various organ magazines to stay current regarding developments in repertoire and the instrument itself. She explains, “There are many magazines on organs, all of them very good. They have instrument specs and reviews of organ and church music, which are really quite helpful” (Matthen 2006). Matthen looks to organ periodicals for both reviews and new repertoire.

Wilson: Rather than ordering or responding to catalogs from specific publishing houses, Wilson relies almost solely on Lutheran denominational materials for his Sunday morning music. The Lutheran hymnal and Lutheran supplemental materials form the core of his sacred repertory at University Lutheran. These materials include lectionary-appropriate suggestions, liturgical settings, and other musical materials. “I’m not sure if other denominations have these things, but I sure am glad we do!” Wilson says (2006). He describes the Lutheran musical resources in terms of their high quality, ease of use, and congregational accessibility. Without years of graduate organ training to familiarize him with the breadth of classical Christian repertoire, Wilson appreciates the convenience of the denominational materials.

Keiser: Keiser describes sacred publishing houses and denominational materials as very important in her experience of a broader organ community. For congregational song, she utilizes the Episcopalian denominational hymnal from 1982 and the two current Episcopalian hymnal supplements. The first, Wonder, Love, and Praise, includes some Taize materials and contemporary songs, while the second supplement focuses on sacred music from African American Christian traditions.

Given her positions both at Trinity Episcopal and in the Jacobs School of Music organ department, Keiser receives “substantial” attention from sacred publishing houses. From Morningstar to Augsburg Fortress to Concordia, quite a number of these companies send her catalogs. Keiser holds these during the academic year and then reviews them during the summer in order to purchase new material.

Webb: While Webb acknowledges that high quality music is currently composed for the organ, he remains content with firm, familiar favorites. He relies upon his years of experience in selecting First Methodist’s traditional Sunday morning repertoire. Webb receives catalogs from some sacred music publishing houses, but he does not find them central to his selecting repertoire. He prefers to preview music in its entirety before ordering it, which he regrets that sacred music publishing house catalogs do not facilitate. In the main, Webb reports being quite content playing Bach, Mendelssohn, Brahms, the French Impressionists and “their slightly less impressive imitators” (Webb 2006). He is unaware of any specifically Methodist musical publications, and does not express any interest in discovering or developing such resources. Webb does not find a strong sense of community through organ publications.

In the end, the four organists’ responsibilities, training, and experience combine to influence their interactions with musical publications. Former Jacobs School of Music dean Webb prefers to play previously-experienced classics, while informally-trained Wilson enjoys receiving and performing new materials from the Lutheran denomination. Keiser reports using a balance of denominational and ecumenical materials, although this reflects her agency in selecting service music. She bears responsibility for selecting both anthems and congregational song. Keiser looks beyond specifically Episcopalian materials for anthems, preludes, and postludes, but Trinity Episcopal has chosen to rely on denominational hymnals and supplements for their congregational singing. Similarly, at First Presbyterian, while Matthen relies on publishing house materials and her own experience in selecting non-congregational repertoire. Matthen does not report using Presbyterian denominational materials for selecting anthems and instrumental music, but congregational song comes from the Presbyterian hymnal. Matthen performs, but does not choose, the hymns; Presbyterian polity dictates that the pastor selects the hymns.

The organists’ interactions with published musical sources position them within two overlapping communities. First, the published organ scores allow individual organists to indirectly interact with the broader organ community. These interactions are not highly interpersonal or dialogic, but by staying abreast of and enacting current musical publications, the organists take part in a form of community. The existence of these print media testifies to the presence of other organists with similar musical needs to their own.

In a related second point, the organists’ cross-denominational reliance upon a relatively narrow range of published repertoire reaffirms the genre of “traditional” worship music. Within the ritual of worship, individual organists are tokens embodying an ideal type. As the organists fulfill musical, theological, and aesthetic expectation of their congregations, they in turn reaffirm these expectations as reality. As ritual specialists within the “tradition” of mainline Protestant worship, organists do not frequently improvise or compose new music for each Sunday service. Rather, they are expected to perform existing pieces of sacred music in a classical style. Denominational materials and publishing house sacred repertoire work within, and reinforce, this system of musical transmission and performance. This continuity of “traditional” church music, in turn, reinforces an implicit community of organists.

Community through Organ Events

Attending live organ events—conferences, concerts, or competitions—provides opportunity for face-to-face organist interaction. While publishing house catalogs create an abstract, cerebral forum for community, live events provide concrete, experiential communication. Attending organ events played different roles in building community for each of the four Bloomington organists.

Webb: Webb’s comments on organists attending each others’ performances reflect a problem inherent in organists observing organists: most of them work similar hours on Sunday mornings. Webb notes that, “It is difficult to visit other churches because I am always sitting on my own organ bench on Sunday mornings” (Web 2006). However, Webb does find it important to build community with other organists though hearing them play and conversing with them. He explains, “If I am ever in New York on a Sunday, I do try to go to St. Thomas [Episcopal]” (ibid.). Attending worship at such a flagship congregation provides Webb with an ideal example of organ music in “traditional” mainline Protestant worship.

Wilson: Wilson feels connected to other organists through face-to-face encounters. As mentioned previously, although he does not site the AGO itself as central to his experience of organ community, he does find some of the group’s offerings helpful in connecting to the broader organ community. He occasionally attends live performances and workshops sponsored by the Bloomington AGO chapter. Additionally, he independently attends concerts and visits other churches whenever possible. Given his Sunday morning duties, however, such church visitation is infrequent.

Keiser: As the organist for Trinity Episcopal, Keiser works within the Anglican Communion.13 While there are no other Episcopalian churches in Bloomington, Keiser does participate in the national Association of Anglican Musicians. In addition to taking part in this sacred music group, Keiser finds attending organ-specific events to be extremely important in community building. She also described such collegial activity as being a general professional courtesy. “We really need to work on this; a lot of organists don’t go to things that their colleagues do. But it’s so important, this kind of reciprocal support” (Keiser 2006).

Matthen: Matthen is alone among her colleagues in mentioning former students as a source of musical connection and inspiration. She reports maintaining beneficial connections via concert attendance and correspondence with a number of former students who are now established organists. These students form overlapping personal and professional community for Matthen.

The four organists interviewed feel that attending live organ performances significantly impacts their experience of an organ community. They express a general desire to support live organ events. The organists believe that attending these events fostered positive relationships with their fellow organists, as well as being potentially beneficial to their own playing. Although regular Sunday morning play schedules keep most organists “tied to the bench,” occasional Sundays off and organ concerts provide opportunity for community building.

Webb is the only surveyed organist to mention this outlet for musical communication. Webb lists “Pipe Dreams,” a nationally syndicated radio show from American Public Media, as one of his primary influences in terms of hearing new repertoire and styles. The show’s website reveals a community of listeners, many of whom are organists. None of the organists interviewed speak of listening to recorded organ music on records, cassette tapes, compact discs, or MP3s. Despite the inherent difficulties of hearing other organists’ Sunday morning performances, recorded music does not seem to be central to transmitting organ music or building a sense of organ community.

The strongest sense of community articulated by the Bloomington organists hinges upon their collective identity as ritual specialists during the contemporary religious restructuring of the United States. This sense of community came across most strongly when I asked the organists what sort of considerations they took into account when selecting Sunday morning repertoire. Even considering only open transcripts, the organists’ comments reveal interestingly similar aesthetic and theological values driving their musical choices. However, when considering their responses—and especially their word choices—within the specific synchronic context of current mainline Protestant worship, the hidden transcripts of their responses bespeak a specific shared ideological position that is often articulated in direct response to “contemporary” worship music.

Focusing on organists provides a unique analytical angle for understanding perceived threat and community formation. While ethnomusicologists often talk about marginally surviving music cultures or vanishing musical traditions, Western classical music has not so frequently been the music culture on the decline. The rise of praise and worship music, however, has brought a historically unprecedented challenge to the hegemony of mainline Protestant organ music in worship. The worship wars of the late 1990s have settled from an openly-antagonistic rolling boil to an unresolved simmer. For many mainline Protestants, guitars and electronic keyboards now form a viable – if not preferable – alternative to pipe organ music. Although very few prognosticators predict the imminent demise of “traditional” organ-based Sunday-morning church music, “traditional” organ-based services have indeed lost their historical hold over mainline Protestant religious practice.

This shift in musical hegemony and the perceived aesthetic and theological contrasts between “traditional” and “contemporary” worship form a point of ideological community for the Bloomington organists. All four of the organists interviewed expressed similar personal values that support the “traditional” style of mainline Protestant worship. While voicing this support, they employed subtle emic linguistic indicators to establish a hidden transcript of opposition between their value system and that of “contemporary” church music.

Matthen: As we were talking about the organ music that she typically plays at First Presbyterian on Sunday mornings, I questioned Matthen about her preferences for musical genre in worship. “What genres of music do you tend to use?” I asked. I purposefully posed the question vaguely to give her freedom to answer. Nevertheless, given the course of our discussion, I was expecting a somewhat technical reply about Bach versus Brahms or other sub-genres of organ music. However, given the broader context of the worship wars, my use of the term “genre” elicited a differently calibrated reply. She replied,

I am not trained in, or interested in, “contemporary” music. But I push the envelope as much as I can, for my personal aesthetics and those of the congregation… I want a unified service, a musically coherent service. I was never a blended service14 type of person. (Matthen 2006)

Matthen’s reply speaks directly to both abstract and concrete issues embedded in the contentious contemporary versus traditional dichotomy. In terms of aesthetics and theology, blended worship elicits a continuum of responses. On one end, proponents of blended worship claim that musical eclecticism positively reflects the long history of Christianity, which theologically depicts an active, multi-faceted deity able to reveal various dimensions of being over time through different musical genres. Those on the other end of the continuum, however, prefer worship within a narrower range of aesthetic options. For them, the range of genres detracts from, rather than intensifies, the profundity of worship. For Matthen, while a degree of aesthetic flexibility “pushes the envelope” in a good way, too much leads to incoherence.

Beyond such abstract issues, Matthen’s comments about her lack of musical training in contemporary music reference practical aspects of the contemporary-traditional dichotomy that directly impact organists as a community. Like other church organists who have dedicated decades of their lives to mastering Western classical church music, Matthen recognizes “contemporary” music as a distinct musical genre for which her years of training did not prepare her.15

The lack of desire or ability to musically code-switch between “contemporary” and “traditional” music present a problem to Matthen and other organists. Church music budgets typically compensate organists as part-time employees. In Bloomington Keiser reports knowing of no full-time organists (2006).16 With many mainline churches accommodating the additional expense of a praise band-driven contemporary service, music budgets are stretched further. The musical diversification of mainline Protestantism’s restructuring has made organists more aware of their stylistic abilities and related aesthetic values.

Now that “traditional” music has lost its monopoly over mainline Protestantism, organists form an ideological community that defines their identity through negation. It may be difficult to describe what “traditional” church music is, but its supporters use the language of the worship wars to clarify what it is not. Communities often coalesce in response to perceived threat, and Wilson’s comments demonstrate that organists are no exception.

Wilson: During our interview, Wilson reacted strongly to many “contemporary” church music proponents’ complaints that organ music does not allow them to “feel” God’s presence. Wilson counters this argument with the “traditional” rhetorical opposition of temporary feelings of excitement versus genuine lasting contentment.

Traditional music is the best vehicle for carrying both doctrine and carrying God’s word and supporting teaching of God’s presence in the sacraments and not how religious we feel in church. Traditional music and contemporary liturgical music can sustain these things over long periods of time, centuries, otherwise people are mistaking excitement for faith… People might not be used to it [the music] when they get here, but they find it beautiful, because we do a good job with lots of substance. (Wilson 2006)

Wilson asserts the affective quality of his music by countering criticism with truth claims of his own about the empirical superiority of “traditional” worship music.

Wilson’s seemingly-contradictory reference to “traditional music and contemporary liturgical music” reinforces the syntactic complexities of the worship wars. The labels “traditional” and “contemporary” imply chronological distinction, but instead, they refer to stylistic difference. As mentioned previously, all of the organists report incorporating new pieces of music into their Sunday morning repertoire. The liturgical musical supplements that Wilson receives from the Lutheran Church also offer recently-composed musical works. These pieces are, however, composed in the “traditional” style. Wilson’s comments reveal that he does not dismiss contemporary worship music, but rather “contemporary” worship music.

In lamenting the lack of substance in “contemporary” music, Wilson introduces another theme prevalent in “traditional” worship music discourse: perfection. Speaking of musical execution, form, and genre, Webb and Keiser echo his sentiments.

Wilson: “Explanations might differ, but it is important to give God your best on Sunday morning. People have put some much thought into perfecting this music that we should preserve and pass it on” (2006).

Webb: “It is sad that some people haven’t embraced the traditional musical literature as much as they could. It is absolutely important that we give our best to God on Sundays” (2006).

Keiser: “I have all the hymns memorized, but every week I practice the ones for the upcoming Sunday for three or four days. It is important to have them perfect” (2006).

For these organists, perfection is a pervasive value that influences many aspects of their musical worldview. Keiser comments directly on technique and quality of performance, while Webb and Wilson reiterate the theme of perfection in a broader sense. Webb and Wilson equate “giving their best to God” on Sunday with “traditional” music. Musical perfection involves theological truth claims, definitions of quality, and choices of musical genre. While they do not directly reference “contemporary” music as less than perfect, their language ties into broader worship wars rhetoric that positions “contemporary” praise and worship music as accessible and participatory while positioning “traditional” music as perfect and professionalized. In contrast to the worship wars’ rhetoric, the organists’ comments affirm their music as both perfect and accessible to worshipers.

The perfection-participation dichotomy is not new to the study of sacred music, from Gregorian codification to Vatican II’s vernacular masses and from shape note schools to Lowell Mason’s arrangements, scholars, theologians, and laypeople have long debated the merits of music reflecting divine glory and perfection or divine mercy and participation. This current language of “giving one’s best to God” both stems from and gives fodder to the fire of the worship wars. It is clear that the Bloomington organists assign added value to sacred music within the “traditional” genre. By more highly valuing this genre, they in turn affirm their own professional necessity and personal contributions to mainline Protestant worship.

This article began by posing simple questions: Do church organists create musical communities? If so, what forms and functions do such communities have? These questions take on heightened significance in light of contemporary developments in mainline Protestantism. The so-called religious restructuring of American Christianity in general, and of mainline Protestantism in particular, has resulted in classical organ music’s displacement from its centuries-long hegemonic hold over Sunday morning worship. Organists are increasingly aware that they are ritual specialists representing one small branch of Christianity in a mass-mediated global religious marketplace.

The four mainline Protestant organists interviewed come from slightly different educational backgrounds, but they share similar musical responsibilities, aesthetics, and repertories. Western classical music training that is the culmination of years of study, or at least functional fluency within this system, provides a formative characteristic of their professional identities. They perform similar duties each Sunday morning within about a four-block radius from each other. But, do these musicians, who perform such similar functions, interact with each other in social or professional communities?

Although the organists feel it is generally important to hear their colleagues play, they report very little face-to-face personal interaction with each other. As Webb explains, “Church organists have an inherent difficulty” in that their presence is completely necessary on Sunday mornings (ibid). Moving beyond the confines of individual experience in their own worship services presents a problem for gainfully employed organists. They do not report perceiving a particular sense of a Bloomington organ community.

Yet, the organists do feel as though they are part of a larger organ community. This sense of belonging comes indirectly; it is only tangentially related to organized professional societies, publications, or denominations. Rather, in the current American religious climate of “traditional” versus “contemporary,” organists form an ideological community in response to alternate worship musics. If collective ideology can form a community, then there is at the very least an ideological organ community in Bloomington. Faced with substantial change during the contemporary reconstruction on mainline Protestantism, organists navigate a new professional landscape. Christianity’s ongoing ebb and flow of participation versus perfection has shifted again. The shifting tides both reveal the Bloomington organists’ shared beliefs and reinvigorate these values. As the organists see who they are not, they more strongly define who they are.

1. A thorough analysis of organists’ similar function throughout much of Christianity lies beyond the scope of this paper. Thus, I limit my analysis to mainline, and predominantly white, Protestantism. “Mainline” is an informally assigned adjective denoting the theological moderation and former social prominence of many Protestant denominations. Precise origins for the term remain elusive; coming into dictionary usage in the 1941 (“mainline”), the term means “being part of an established group” or “being in the mainstream.” In religious usage, the term refers to a specific subset of is generally understood to include (at least) American Baptists, Disciples of Christ, Congregationalists /United Church of Christ, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Methodists, and Presbyterians.

2. The so-called “restructuring of American religion” has bred considerable sociological scholarship. See, among others, Ellingson 2007; Robert Wuthnow, The Restructuring of American Religion (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988); Wade Clark Roof and William McKinney, American Mainline Religion (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987); David A. Roozen and C. Kirk Hadaway, eds., Church and Denominational Growth (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993).

3. My use of the term “Evangelical” references William Bebbington’s oft-cited four point definition of Evangelicals as Protestant Christians who emphasize conversionism, activism, Biblicism, and crucicentrism (1989).

4. Such theological conservatism coupled with musical liberalism is not unique to Christianity. Jeffery Summit’s 2000 analysis of five Jewish congregations found that those who (like mainline Protestants) fell into the middle of the liberal-conservative theological spectrum were the most conflicted over musical style, often using the least expressive behavior in worship.

5. I enclose the terms “traditional” and “contemporary” in quotation marks to clarify their usage as labels for worship genres. Although it is tempting to conflate the colloquial meanings of contemporary and traditional with the so-named genres, as styles of worship “contemporary” and “traditional” take on specialized meanings. See Hustad 2000; Langford 1999; Makujina 2000.

6. The field research for this article was conducted in 2006. Since that time, substantial organizational changes have taken place in some of the church music programs addressed in this study. At the time of publication, only two of the organists, Charles Webb and Marilyn Keiser, continue in the same positions. For the sake of clarity, however, I have written the article with the ethnographic present set in 2006.

7. Westhampton College was the female counterpart to all-male University of Richmond prior to the school’s gender integration.

8. Since many of University Lutheran’s congregants are university students, the congregation has considerable annual turnover. It falls to Wilson to consistently recruit new singers.

9. The lectionary is a liturgical calendar.

10. Wilson’s short term of service, five years, considerably lowers the average between the others’ thirty-three, forty-eight, and twenty year terms of service.

11. Mainline Protestant denominations self-report their numbers as: 10,000 Lutheran (ELCA) (“Quick Facts.” 2009); 10,000 Presbyterian (U.S.A.) (“Who We Are.” 2009); 7,000 Episcopal (“Fast Facts.” 2009); 5,500 American Baptist (“Home.” 2009); 3,700 Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) (“Congregations.” 2009); 5,600 United Church of Christ (“About Us.” 2009); and 34,000 Methodist congregations (“Quick Facts: U.S. Data.” 2009).

12. Augsburg Fortress is the publishing house of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA). “Funded through sales revenue, Augsburg Fortress is called to provide products and services that communicate the Gospel, enhance faith, and enrich the life of the Christian community from a Lutheran perspective” (“About Us,” 2006).

13. The Episcopalian Church in the United States retains ties to its British progenitor, the Anglican Church. The Anglican Communion comprises numerous churches around the world with historical and continuing ties to the Anglican Church.

14. A “blended” service incorporates both “traditional” (i.e. Western classical music and hymns) with “contemporary” (guitar and/or keyboard based popular music) sacred music genres.

15. Matthen was keenly aware of these dynamics at the time of our interview. First Presbyterian was working towards the implementation of a “non-traditional” second Sunday morning service with different musical staff.

16. Keiser defines full-time to mean that an organist has only one sustaining source of employment.

“About Us.” Augsburg Fortress. http://www.augsburgfortress.org/company/ (accessed April 25, 2006).

“About Us.” United Church of Christ. http://www.ucc.org/about-us/ (accessed July 16, 2009).

“Advertising Rates.” TAO Magazine. http://www.agohq.org/tao/indexadv.html (accessed July 28, 2009).

Bebbington, D. W. 1989. Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s. London: Unwin Hyman.

“Congregations.” Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). http://www.disciples.org/Congregations/tabid/54/Default.aspx (accessed July 16, 2009).

Ellingson, Stephen. 2007. The Megachurch and the Mainline: Remaking Religious Tradition in the Twenty-first Century. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

—––. 1962. Protestant Worship: Its History and Practice. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

“FAQ.” Presbyterian Research Services, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). http://www.pcusa.org/research/statistics_faq.htm#2 (accessed February 23, 2009).

“Fast Facts.” The Episcopal Church. http://www.episcopalchurch.org/documents/Domestic_FAST_FACTS_2007.pdf (accessed July 16, 2009).

“Home.” The American Baptist Church. http://www.abc-usa.org/ (accessed July 15, 2009).

Hustad, Donald P. 2000. True Worship: Reclaiming The Wonder and Majesty. Colorado Springs: Shaw Books.

Keane, Webb. 2007. Christian Moderns. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Keiser, Marilyn. Interview with Deborah Justice. April 25, 2006.

—––. 1986. Teaching Music in Small Churches. Nashville: Church Publishing Inc.

“mainline.” Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2009. Merriam-Webster Online.

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mainline (accessed July 15, 2009).

Makujina, John. 2000. Measuring the Music: Another Look at the Contemporary Christian Music Debate. Salem, OH: Schmul Publishing Company.

Matthen, Lidetta. Interview with Deborah Justice. February 28, 2006.

Langford, Andy. 1999. Transitions in Worship: Moving from Traditional to Contemporary. Nashville: Abington Press.

“Official Documents.” American Guild of Organists. http://www.agohq.org/about/index.html (accessed April 23, 2006).

“Pipe Dreams.” Pipe Dreams. http://pipedreams.publicradio.org/ (accessed April 26, 2006).

“Quick Facts.” Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. http://www.elca.org/Who-We-Are/Welcome-to-the-ELCA/Quick-Facts.aspx (accessed July 15, 2009).

“Quick Facts: U.S. Data” The United Methodist Church. http://archives.umc.org/interior.asp?ptid=6&mid=2119 (accessed July 16, 2009).

“Religious and Demographic Survey of Presbyterians, 2005.” 2008. The Presbyterian Panel. Research Services, Presbyterian Church, USA.

Slobin, Mark. 1993. Subcultural Sounds: Micromusics of the West. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

—––. 1989. Chosen Voices: The Story of the American Cantorate Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

“The American Organist Magazine.” TAO Magazine. http://www.agohq.org/tao/index.html (accessed April 23, 2006).

Turner, John G. 2008. Bill Bright and Campus Crusade for Christ: The Renewal of Evangelicalism in Postwar America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

“U.S. Congregations.” The U.S. Congregational Life Survey. http://www.uscongregations.org/index.htm (accessed July 29, 2009).

Webb, Charles. Interview with Deborah Justice. April 25, 2006.

“Who We Are.” Presbyterian Church U.S.A. http://www.pcusa.org/navigation/whoweare.htm (accessed July 15, 2009).

Wilson, Chris. Interview with Deborah Justice. March 21, 2006.

Wind, James P. and James W. Lewis, eds. 1994. American Congregations: Volume 2: New Perspectives in the Study of Congregations. Chicago: University of Chicago.