From the Inside Out(er): Issues in Ethnomusicology - The 1995 Seeger Lecture

Professor Jairazbhoy's lecture, originally published in PRE Vol. 7 (1997), is presented here in honor of his recent passing. We are thrilled to bring to the reader the original audio and video, as well as the text, which was not possible in its original publication in print. More information about Professor Jairazbhoy can be found in the links below.

Obituary (by Helen Rees and Donna Armstrong)

Comments and Condolences

The Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy

Scholarship Fund

Apsara Media for Intercultural Education

*From the original 1997 publication:

The original lecture presented by Professor Emeritus

Jairazbhoy was a multimedia experience. What is presented here does its best to capture the spirit of the original, and may well have virtues of its own, but cannot truly represent what was heard at UCLA. The original biographical video, "An Alphabetical Autobiography of Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy: From A to F," was created by Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy. Visual images from the video represented in the text are marked with the symbol below. Hopefully you should be able to follow the text,

the video narrative and the stories.

![]()

Some of you may remember that I was president of this society twenty years ago. Whether or not I was the worst president we have ever had may be debatable, but there is no question that with my curious background and my unusual academic experience, of all our presidents I was the least prepared for the task. Without hesitation I can say that those were the most traumatic two years of my life, when our Executive Board disagreed with me on virtually every issue culminating in the 1976 annual conference in Philadelphia when the membership put me on the spot in a heated open meeting and I finally felt lucky to be spirited away without being lynched. The issue was one of discrimination and a resolution was unanimously approved by the membership that the Society reject advertisements from South Africa on the grounds that they practised segregation and racial discrimination. I felt then, as I still do, that since our society states that we do not discriminate against anyone and accept as members "all persons, regardless of race, creed, color or national origin," we could not refuse to give equal service to our South African members because of their beliefs or practices. The only way I could reconcile my beliefs with those of the membership was to terminate all advertisements, which we did, at least during the remainder of my term.

Not a conventional opening to a Seeger lecture, but then the committee that nominated me can only have done so in the knowledge that I have in recent years been exploring the world of invention and non-convention and would expect nothing less of me even on this hallowed occasion.

For many years now I have felt that one cannot understand the real significance of any statement without knowing a great deal about the person making that statement. If, for instance, it was made by an advertiser trying to promote a product, we would know better than to take it at its face value. The same goes for anyone who has a personal involvement because of nationality, race, color or creed in the subject of his research—and that, I think, includes most of us—not, by any means, excluding myself. On a rather simplistic level we recognize the different attitudes and approaches of insiders and outsiders, but it is a matter of some concern when one reads in a recent anthropological publication, "it is now generally accepted that only the members of each ethnic group can most effectively study, teach about, discuss and generally speak for their fellow group members,"1 as though mere birth into an ethnic group necessarily bestows knowledge and understanding of that group. On the contrary, I would be tempted to argue the opposite, that membership in an ethnic group will very likely incline an individual to present a biased view not unlike that of an advertiser, were it not for the fact that this too would be an oversimplification. No two members of an ethnic group share quite the same background or life experiences and it should be obvious that they will not share exactly the same views.

Since I have been variously described as an insider, outsider and most recently, as an inside-outer, I feel it beholden upon me to give you a brief resumé of my formative years so that you will be aware of the origins of my perspective. I leave it to you to decide which elements and views on scholarship derive from Nature and which from Nurture, or which from culture and which from individual personality and accident.

My grandfather.

My ancestors came from Kutch in Western India where many generations ago they had been converted from Hinduism to the Khoja sect of Islam. The menfolk were traders and merchants and accumulated a considerable fortune in the timber trade with China.

Since they had made lucrative investments in properties in Bombay, they decided to migrate there before the turn of this century. They were also philanthropists and were held in high regard by the community in Kutch as well as Bombay, as was my father who inherited inordinate wealth and devoted much of his life to propagating Islam, writing religious books and practicing philanthropy. He was one of the founders of the Mosque in Woking, England and also donated large sums towards the establishment and support of educational institutions in India for both sexes.

My mother who was also of Kutchi origin, was brought up in Rangoon, and like her mother was a powerful woman with religious as well as artistic inclinations. Kutch is famous for its embroidery and they both inherited this skill, creating representational pieces as well abstract patchworks.

My parents travelled widely in the Middle East and went on the Haj pilgrimage to Mecca and Madina in 1932. My mother being quite progressive, was the first lady to film the event, while my maternal grandmother created a series of embroideries depicting her own memories of the Haj. My father did much of his proselytizing in Europe, USA and Canada where the film received critical acclaim in 1933, but unfortunately, this historical document has since been lost.

The family Daimler.

My father also had another side to his character: he was quite a sportsman, he loved cars and occasionally adopted the attire of an impeccable English gentleman. He also loved to entertain on a lavish scale and I can remember grand occasions with dinner for as many as 500 guests. There were also receptions when, for instance, a European family adopted Islam. Unfortunately, I had little opportunity to get to know my father as he died when I was ten, soon after hosting a major international conference on Islam in our palatial family home…

What on earth happened here?

I guess I blew it.

I can't believe that you'd let me down on such an important occasion.

It's all those rehearsals and looking at your face endlessly.

I can sympathize--but with all those rehearsals you ought to be more efficient.

I got mesmerized and must have dozed off.

I suppose its understandable, but what a time you picked!

I promise to make up for it. While I cue up to the next part. why don't you do something you're really good at: Tell them a story!

Alright, I suppose I have no alternative. Well I just happen to have one which might amuse you. This story is in the vein of my book, Hi-Tech Shiva and Other Apochryphal Stories, but much shorter (Jairazbhoy 1992). For those of you who are not familiar with it, I offer a few words of explanation. Stories told by Indian storytellers frequently depict the Hindu Gods as having human fallibilities and have no qualms about drawing these to the attention of their listeners, as I do in my Shiva stories. In these the setting is Mount Kailash, abode of the Hindu Gods, which is not unlike some of the elite residential areas in this city and others in the world. The Gods finally have acknowledged that their creation, the human world, has once again failed and must be destroyed. But Shiva, the King of Gods, is convinced that before he destroys the earthworld, the Gods must carry out fieldwork in order to understand why their creation failed, and in the process they face problems and issues, both on heaven and earth, that many of us have encountered in our university environments and in the field. This is a kind of "serious fun" which I hope you can enjoy with me.

Now the story, entitled,

As Shiva's term of King of the Gods was approaching its end, the CNN—that is, the Celestial News Network—organized a debate involving the leading candidates: the incumbent Shiva, Vishnu, leader of the opposition and an unlikely-looking Independent candidate with big ears—very like an opossum from Okefenokee swamp—by the name of Peroswami.

Mount Kailash, the home of the Gods, which has more than a superficial resemblance to the Hills and Aires of Beverly and Bel, was agog with excitement. They knew that Vishnu was out to get Shiva and prove that he was not worthy of being at the helm of the Gods. During the course of the debate, Vishnu, so to speak, 'steered' Shiva into a confrontation on ethics and violating something of the code of debating behavior, he addressed Shiva directly:

"Ever since the threat of the universal cataclysm, you have been carrying out fieldwork on earth and documenting human traditions with your Hi and Super fancy video and audio recorders, not to mention their digital mutants. We all know that you have a lofty purpose in mind—namely your concern that the designers of the universe don't make the same mistakes they made last time. But what about the fact that you are also recording mankind's best songs and dances and exposing them to everyone on Mount Kailash. How do you justify that?"

This question didn't bother Shiva and he replied confidently:

"Well, I'm not exactly a commercial recording company, you know. Anyone will tell you that I am not out to make money and I think you'll agree that I don't need to be more famous, right? But seriously, my main concern is to find why we've failed again and human music and dance traditions are only incidental. I can't say that I don't enjoy them—and I wish we Gods could come up with such a fascinating variety of traditions, but we evidently don't have either the artistic genius or the patience of mankind."

"That's all very well," Vishnu said, "but you can't deny that many of the Gods and Goddesses only attend your soirées for the music and dance and not to play ping pong or to discuss intellectual issues. And now some of us have actually begun to play exotic instruments, like that long string instrument from India and a gong-playing group has just started up on Skyline Drive. Who owns the music, anyway? And what right do the Gods have to appropriate mankind's cultural traditions?"

Shiva was thoroughly riled by this and responded with some heat.

"Now wait a minute. We created humans, so everything they create really belongs to us. Just like when we conquer demons, we loot and pillage and take whatever we want. What's wrong with colonialism? In any case, how can they stop us? Let Mount Kailash ring with alien gongs and bells—if that's what our Godlings want."

"I happen to be concerned about ethics," Vishnu replied sternly, "and I'm very concerned about the ethics of what you're doing under the pretext of advancing knowledge about this creation. Maybe you don't charge admission for your video and audio shows, but you can't deny that you don't exactly discourage voluntary contributions to support your next campaign. It's common knowledge that you're using the shows to advance your personal popularity and pick up some of the swing votes. All good scholars follow the guideline that their first obligation is to their subjects and not to advance their own ends. The least you could do is to pay the performers royalties for each vote you pick up."

Peroswamy was feeling left out and finally broke in, in his thin, reedy voice.

''Let's talk about taxes or social security or the national debt, instead of trying to pin each other down on a matter of ethics. Even the OJ non-conviction is more interesting than all this 'holier than thou' stuff about ethics. Now we all know that there is going to be no next creation if we don't get rid of our massive entropy deficit. Why don't we talk about that? And Shiva should stop coming up with zany ideas, like Hi-Definition TV for his White House research projects as we keep going deeper and deeper in debt. So let's tackle the real issues."

Shiva didn't hear a word Peroswamy said. He was too busy trying to think up a response to Vishnu's comment about royalties and spoke out almost before Peroswamy had ended:

"Now why in heaven should I have to pay royalties? I have classified all earth creations as folklore, and as such, they all fall in the public domain. Copyrights only apply to individuals living in superior societies, like ours, so there is no question of royalties to be paid to humans. If anything, they should pay me for making their traditions known on Kailash. Perhaps my son Ganesh who's always talking about starting a new business will invite the best of them here to give live performances so that they can add the initials KR after their names—you know, 'Kailash Returned.' That will give their careers a big boost. And all because I took the trouble to record them in the first place."

"Maybe," Vishnu replied, quite unconvinced. "But you're avoiding the main issue. Your primary purpose is to enhance your own goals, whether in the interests of creating a perfect future universe or picking up swing votes. You are not concerned, in the first place, with the well-being of your subjects as our Ancestral Astrological Association has laid down."

"With all due respect," responded Shiva with exaggerated humility. "You have the wrong end of the stick, if I say so myself. Even though I knew I was doing them a favor—not the reverse—I paid them all and they were happy to sign release forms giving me full rights over the recordings. So you see, I have no further obligations to them."

"But did they really understand what rights they were conferring on you?" Vishnu responded heatedly. "And you say you paid them but by whose standards? Theirs or ours? If you're showing the tapes here on Kailash, don't you think they deserve to be paid at our union rates?"

Peroswamy was obviously getting exasperated and broke in with a voice that was nearly cracking.

"Stop! Stop! This is going nowhere, and besides, you're only trying to jack up our deficit, Vishnu. We have to stop paying out so much and cut down on the fat, I keep saying, and yet no one wants to look at the real issues. Focus on the real issues, or I'm OUT."

But there was no restraining Shiva.

"You forget one thing, my friend Vishnu," he said, ignoring Peroswamy again. "We don't have unions on Mount Kailash. If we did, Gods forbid, their rates would no doubt be high, at least by earth standards. Paying musicians at that level would ruin the economies of their countries. Before long inflation would set in, currency devalued and everyone would blame the musicians. Soon they'd be back at the bottom of the totem pole. No, my friend, our standards are not for

developing earth worlds."

Vishnu was not about to concede and Peroswamy like a terrier was not about to relinquish his monopoly on the issue of issues. And so the debate coiled on into the night with the Gods and Goddesses nodding off one by one and blankening their screens.

Which reminds me, hoping that our trusty assistant has cued up the display by now, we can turn on our screen.

The family home.

It was on one of their travels to England that I was born, but a few weeks later we boarded an ocean liner for India in time for a seafaring Christmas party. Our family home in Bombay was a wondrous mansion situated on about six acres of fabulous garden overlooking the ocean. Being the youngest of four boys and five half siblings, I was naturally doted upon and thoroughly spoiled. I thought that I could get away with virtually anything and took great pride in feigning innocence while pulling off my pranks. Growing up was a lot of fun—one of the advantages of a large family, always games to play, lots of kids to play with and mischief to get into. And we had the greatest toys brought back from Europe by my parents. I always liked games more than school and avoided kindergarten for about six months by hiding in the garden when the chauffeur came to take me in the mornings.

True to Bombay's multiculturalism, I attended a Catholic kindergarten and then a Protestant School where one of my best friends was a Jewish boy.

Among my fondest childhood memories was the trip with my parents to our ancestral lands in Kutch, where we visited the first school in the area established by my grandfather. My brothers were away in boarding school and missed out on the fun bullock cart rides and being entertained by nobility in nearby Saurashtra. In those days, we too were regarded as such, and were even included in the Who's Who of Indian Nobles.

My parents.

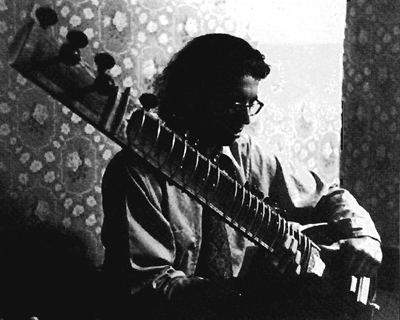

Ever since I can remember, music was a major part of our life, both Indian and Western. We all took Western violin lessons, but I was much more attracted to the sitar which my mother played and frequently sat by her side while she practiced. Her sitar teacher, Madhav Lal of Mathura, lived on our premises and played or taught us whenever we wished. I found the instrument irresistible and began lessons with him when I was only 7 or 8. Over the years I developed a deep relationship with Madhav Lal who was an extraordinary teacher and still have some of the notations he prepared for us. When next I returned to India more than five years later, he had evidently disappeared in the turmoil of India's independence and the split of the country to create Pakistan.

My uncle Yacoob.

We also had all-night Muslim religious qawwali sessions in our home, but when my mother's younger brother, Yacoob, decided to become a professional qawwal, it caused no little consternation in our family—music could be tolerated as a hobby in our community, but not professionalism. He persisted, however and I recall playing occasionally with his group when I must have been only ten or eleven.

My parents were influenced by what we might call Occidentalism as were other wealthy Indians so we were sent serially to boarding school in England. My turn came in 1939, but after just three months there, war broke out and terminated my English school days. I and two of my brothers were then packed off to the nearest thing in India, the newly established Doon school with its Rose Bowl amphitheater in Dehra Dun based on the English public school system. I did not exactly cover myself with glory in the academic sphere and was far more interested in sports and music than anything else. But the kind of egalitarian conditions imposed in boarding schools must have had a major impact on me.

I travelled in one of the early American troop ships converted for civilian passengers in 1946—an amazing transformation of realities—cabins for fifty and more on stacked bunks and no privacy but plenty of companionship.

Me.

The USA wasn't quite what I expected, although I was fascinated by the dramatic countryside and motored frequently throughout the western states. But I had a great deal of trouble adjusting to the life of a student far from home in such a radically different environment. At the University of Washington I continued to be more interested in sports than studies and my academic scores were far from brilliant. I also discovered that I didn't have a very high I.Q. I found that I did not have the intellect for Aeronautics, gave up and switched to Architecture then moved to Art and would perhaps have kept going down the academic alphabet list, except that I was constantly in financial difficulties and was obliged to stir myself from indolence to find employment—anything from busboy to manual labor. Being on a student visa, I was not permitted to work off campus and was eventually caught and given 6 months to leave the country. With my existing coursework I found I could complete a BA only in Geography in that period and did so. Even though I had married an American woman, my visa could not be changed while I was still in the US.

So we went to India and I tried to find employment, but there were no openings in geography. I resumed my sitar training with a young man who claimed to be Madhav Lal's son, but he soon absconded with all my instruments. I also worked as an unpaid draftsman in an architect's office with no real prospects without a degree. After a year I was informed that I could get a green card and decided to return to Seattle to study architecture once again. But having no scholarship I accepted a drafting job in an engineering firm, where I was continually demoted until I was doing heavy physical labor in their structural steel shop. I finally quit after 6 months and decided I was going to be a painter and resumed practice on the simple sitar which I had just received from India.

In the next year or two, I actually had a fair amount of success and exhibited my paintings in numerous galleries, earning almost as much as I had done as a steel worker. One event had a major impact on my future. Dr. Richard Waterman was then teaching a course called "Primitive Music" at U. of W. He heard me in an art gallery attempting to interpret paintings on my sitar, and invited me to give some talks in his course. I agreed and decided to do some library research to help me organize my talk. I couldn't believe it—little of what I read related to my knowledge of the subject and the lectures and my demonstrations, I am sorry to say, were not very good. Two years later these lectures were released as an LP by Ethnic Folkways and, distressingly, it has recently been re-released as a CD.

Painting had become a major obsession in my life and I could think of nothing else day and night. What made it so serious was the fact that my wife had just given birth to a child—and I was so lost in my own world that I gave her little physical or moral support. She left, and I found myself the sole caretaker of our year-old daughter. I could no longer paint and following my mother's urgings, we journeyed to Pakistan to give her a stable home and for me to resume my study of Indian music.

I was due to study with Ustad Bundu Khan, the legendary sarangi maestro, but unfortunately, he was ill when I arrived and passed away shortly after. So I studied for more than six months with his son, Ustad Umrao Bundu Khan, a vocalist and sarangi player, learning new rags, and with Ustad Fateh Ali Khan, a surbahar player concentrating on technique and improvisation.

Then unexpectedly, I heard from my brother advising me to come to England to study with "the greatest scholar of Indian music, Arnold Bake." And of course I went.

I want to draw your attention briefly to the highlights of some of my experiences in SOAS.

1. Arnold taught only one course, one hour per week on Indian music.

2. There was no pressure either on him or myself to recruit students and most of our teaching was to classes that seldom exceeded 10 students.

3. We were not faced with student evaluations.

4. Department meetings were usually not more than once a year for one hour.

5. I was seldom asked to write letters of recommendation for either students or colleagues.

6. I was appointed Lecturer, which is the equivalent of Assistant Professor in this country with only a B.A. in Geography.

7. I was given tenure in 1967 without any review of my work, to the best of my knowledge.

8. When I approached my Chair about the possibility of my proceeding to a Ph.D., his response was very negative. "Why do you need a Ph.D., you already

have tenure?"

9. Nevertheless I proceeded to register for a Ph.D. and all requirements were waived on the grounds that I was already a tenured Lecturer. M.A. was deemed unnecessary. No coursework required. No languages were required. No qualifying examination was required. I was merely asked to submit my dissertation.

10. I met with my dissertation supervisor just once, for ten minutes.

11. For my dissertation I submitted my book on rags which had just been published. The oral was tough, but my book was approved and I received the Ph.D.

from the University of London in 1971.

Had it not been for this soft academic structure, I would not be standing before you today. I am quite sure that I would not be able to pass the Ph.D. qualifying examinations required of our students in UCLA. In fact, I do not think that I would even have passed the entrance requirements for our graduate program, and I am sure that if I had been accepted, I would have found the course requirements so tedious that I would have given up and moved to the next letter in the academic alphabet.

From my perspective the academic world in the US is far from what I had expected. In my naive view a University was a place to make discoveries, not only about the external world, but also one's own self. It is the challenge and excitement of discovery that I find lacking, at least in the humanities. What we have instead is a very practical approach to education, which, surprisingly to me, carries over on to the graduate level. Students are being trained to have the kind of well-rounded background that professors think will not show up the university in a negative light. A Ph.D. from a particular highly-regarded university will be expected to know x, y and z, therefore we must ensure that all our students know these subjects well. So we make required courses, prepare elaborate syllabi, give plenty of readings and extensive bibliographies, give assignments and often tests, if not for each specific course, at the end of the students' training, in the form of qualifying exams.

In the first place, syllabi are restrictive and take away from the element of spontaneity. They leave no space or time for the Professor or students to explore new directions. I sat through six years of Arnold Bake's lectures on Indian music and one of his greatest delights was to surprise me by coming up with something new. Of course, he gave no assignments, no required readings and no tests. To me, these are all forms of indoctrination which force students into particular molds, and although they are based on traditional concepts of scholarship that we have inherited from Europe, we in this country have chiselled them into stone. We may talk about being egalitarian, but, in fact, we are imposing these views on students, regardless of their cultural or racial backgrounds. Perhaps the most detrimental notion is that ethnomusicology is a Western invention, with the implication that it will always remain so. No doubt, the West has contributed significantly not only to the creation of our field, but to civilization in general, but the recognition of the contributions of other cultures is now long overdue, especially in this multicultural society. I mean the contributions of Bharata and Bhatkhande, of Lao Tse and Confucious, of AI-Farabi and Safi-ul-Din, of Pythagoras and Plato, to name just a few of the most prominent pre-ethnomusicologists.

One thing I have learned from storytellers in India. Don't belabor a point. Once it is made, move on. The best anecdote for the potential intellectual logjam created by controversial ideas is humor. And what better than to make fun of ourselves. So here goes.

The word ethnomusicology, as we are told, was originated by Jaap Kunst in the 1950s, but the perspective I am about to unfold may bring even this into question. The first comes from classical Greece.

Etiology of Ethnomusicology - take 1

When Greek civilization was at its height and there was an outpouring of monuments and sculptures that reflected its glories, Athens became the tourist capitaI of the world. Many came from Scythia and Phrygia, Lydia and Phoenicia, they came, they saw and were conquered by its beauty and magnificence and many stayed to enjoy the fruits of this spectacular civilization. A generation or so later, there was growing concern that the kind of classical education being provided to the multicultural youths of Athens was ethnocentric and was not reflecting the growing diversity of its population. Soon panels and committees throughout Athens were considering modifications to their courses on civilization and culture to include a broader base which would not exclude the backgrounds of their recent immigrants.

After a great deal of deliberation it was finally agreed that the parties concerned could not possibly reach a consensus view. They then took the matter up to a higher level and turned to the great God Apollo to seek his advice in the matter.

Seated in his cavernous sanctuary in Delphi surrounded by the mists of prophecy, they approached him with their dilemma. As usual, when invoked in such instances, Apollo, in turn, invoked the oracle of Delphi and after much music and incantation, the oracle struck again. The priestess, Pythia, inspired by Apollo's lyre, fell into a trance and swaying crazily from side to side, she began mumbling in a language that once had been but now could only be understood by priests. Slowly, as the priests translated her jumbled words and Apollo made sense of them, hope and anticipation turned into certainty: the dilemma would soon be resolved. The solution was startling in its simplicity. What was needed was to add a tenth Muse to the existing nine, one well versed in the music and arts of the non-Western world. And so was born the Ethno Muse.

It is never easy to convince the establishment of the validity of any radical departure from accepted customs and practices, yet, the oracle had spoken, so it was implemented. The Ethno Muse was born and perhaps because she was the youngest, was doted upon, or because what she had to offerwas so startlingly new, she made the Grammys almost immediately and amassed a huge following. Naturally, this was not without its complications and it became obvious that this new element was disrupting the ecological balance of Athenian society. The poor Ethno Muse found herself facing discrimination of all kinds and had it not been for Hesiod who took it in his mind to champion her cause and give her a divine origin she might well have been driven underground and upset conditions there as well. But some scholars delight in just such issues and made her the subject of their study and her impact on the environment, introducing, for the first time, a new subject, Ethno Muse Ecology.

My second scenario is set from the cavern of Delphi to a remote cave in the Himalaya mountains where an intrepid reporter finally beards his prey after weeks of harassing adventure and personal hardship. His prey is, of course, the phenomenal swami, the one and lonely transcendental guru, Sri Spaced Out. Notwithstanding the remoteness of his lair, his reputation had spread far and wide even without the help of Bell, AT&T, Sprint and MCI. How? we might well ask, and indeed should. But to understand such nebulous cosmic waves, one would also need to be spaced out. This did not at all deter our intrepid seeker of truth.

Etiology of Ethnomusicology - take 2

"Swami" he proclaimed breathlessly at their first meeting, reflectlng and exaggerating the physical demands of his search. After a second breathless "Swami" he put it all in a single nutshell: "How do you do it?" Then feeling that he needed to fill his readers in, he continued. "I mean how do you know what's going on in our world, since you've been living in isolation in your cave for more than twenty years, without the benefit of BBC, CNN and all the other dedicated news stations?"

"Have you not heard of cyberspace?" asked Swamiji. "If you haven't, you soon will. But I don't go in for all those new-fangled human innovations. I just look within myself and there lies the answer."

"But Swamiji, I've come all the way up to your mountainous lair, because word reached us in the plains that you are finally going to reveal it all."

"That is true, but it is also false."

The reporter, thinking "Oh! Oh! not another enigmatic swami!" replied with an exaggerated air of patience, "Perhaps you would be kind enough to elaborate.” To this Swamiji responded:

"It all depends on what sense you use, common or non. You see most of us have been getting by using commonsense, because it seems to work. But it really doesn't—it just seems that way. The universe actually functions in a non-sense way. By that I mean our senses are at complete variance with universal functions."

Swamiji sensing the reporter's instinct to pin down his interviewee, continued, "Don't be impatient. Time is on the side of the patient patient. What I am saying is for you to hear, digesting it may be difficult. You see our scientists tell us that we are spinning around our axes and also orbiting elliptically around other bodies and all at furious rates. Is this really true? Do you feel It? What this hides is my reality and your reality. I feel no spinning or eillpticisms, only a gentle swaying—the swings and arrows of outrageous fortune—as one of our bards has expressed it."

The reporter, delighted at finding a flaw in Swamiji's statements says, with exaggerated humility, "Pardon me sir, with all due respect, but I think he said 'slings' not 'swings.'"

"Now that you mention it," Swamiji responds, "I must accede to your scholarly bent. But it is the swing that I see—not the sling. In any case, slings are a bit passé, don't you think? Perhaps the copyist slipped when copying the bard's manuscript. I see that your patience Is beginning to run thin. I suggest that this is due to too much aspirin in your system. Go easy on it and life will take on a more poignant hue and you will be more responsive to the swings and arrows. And you may well ask: what are these swings and what the arrows? You see, common sense tells us that scientists must be right. Spinning and ellipticizing we may be and at furious rates. But no sense makes sense of this. What the scientists don't emphasize is that we are also swinging, like pendulums, back and forth, back and forth. And when the Lord said, 'Go forth,' we did, but we also came back. Of course, He knew. But that was his way of starting the swing of the pendulum.

"Now we take a break for our very special brew of tea, caffeinated Ayurved Mountain Blend."

The Reporter could not help but wonder, "Coffee and tea breaks here? But why now?"

Swamiji anticipating the Reporter's question, responded, "I know that you are wondering why I called for a tea break just then. The pendulum swings, but at the end of every swing there is a moment of stillness and that is the pause that refreshes—the tea break—and it occurs again and again. Thus our special brew—to prepare you for the accelerating down swing where truth lies—and then as deceleration begins we see that truth lies and lies and lies. Then up again on the other side to another cup of our special brew, to prepare us for another accelerating swing of truth."

The Reporter then broke in with, "But where do the arrows come in to the picture?" To which Swamiji responded:

"Arrows have sharp points that make their targets resonate when they strike. So, too, at particular points of the pendulum swing our bodies and minds suddenly resonate with convictions, just as though we had been struck with the arrow of the most important reality. It could be an issue, like racial discrimination, political correctness, or affirmative action. But these are just points in the swing of the pendulum and no matter how violently we resonate at that moment, they will be gone. And after another break for tea, we will see the other side of the picture and have new resonances."

After the break that refreshes, the Reporter continued his questioning: "Swamiji, I don't understand how you could possibly know what is happening in our world below while you sit in your remote and isolated cave."

"Well, you see, I think a great deal," responded Swamiji.

"But how can thinking on this remote glacial peak help you to know what's going on in our plains world?"

To this Swamiji expounded: "It's really an understanding of swings. If today the diffusion of ideas is Out as a scholarly approach, then it is easy to predict that it will again become In when the pendulum swings back. If today we discriminate against any group or groups, the pendulum reversal will ensure that it will be reversed. Affirmative action becomes affirmative discrimination. Top dogs will be bogged down into bottom dogs. If the new toppers understood the pendulum, they wouldn't celebrate too much, their heyday will soon become their naydays. Back and forthism is our only non-sense reality, not the spinning or the ellipticisms."

The Reporter, finding this beyond his comprehension, then changed the subject: "I think I'm beginning to see, but why did you retreat into the mountains and become a swami? Weren't you once a famous professor of musicology in the USA?"

"Well there you have it. It wasn't musicology. It was ethnomusicology," responded the Swami.

Not unnaturally, the Reporter was taken aback by this strange term, "I've never heard of that. What's ethnomusicology?"

Swamiji now responded, a bit defensively, "That's always been our big problem. No one knows what ethnomusicology is about—not even ethnomuslcologists. And that in itself is enough to drive one into the mountains."

"But Swamiji, someone must have known, otherwise they would not have appointed you as a Professor of Ethnomusicology."

"Well, people who call themselves ethnomusicologists have certainly tried to define the field and even tried to convince others that it was a discipline. But I was never convinced, and so I was glad to escape to my retreat."

"That is quite unbelievable. Would university administration—which is always strapped for money—create professorships in a field that nobody understands?"

Swamiji responded, "That is a small nothing. University administrators have created whole Institutes and Departments in fields that don't exist!"

Not unexpectedly the Reporter was confused. "I must be missing something. Could you please try to tell me something about ethnomusicology?"

"Well, I guess," Swamtii responded, "it is really what ethnomusicologists do, and they do a great variety of things. They write books and articles about strange music and play strange instruments. But mostly they say that they study music in the broad perspective of society and culture."

"Does that mean they don't study music for its own sake—I mean as an art form?"

Swamiji then made a definitive statement, "Some people would call that musicology and ethnomusicologists don't like to be branded as musicologists. That's why they came up with the name eth – No Musicology. And even that 'eth' was really a lisper's ellipsis of 'yes,' so that it was originally intended to be, 'Yes, No Musicology'."

The Reporter, trying to make sense of all this, "I find this fascinating. I've never heard of a discipline with such a strange name. As long as it is not musicology, is every other approach to music acceptable? I mean, what if an ethnomusicologist decides to relate music practices to the occult sciences or to obscure mandalas of perceived cognates? Or for that matter to the sounds of nature, or even the rhythms of outer space?"

"I guess it's been done. The ancient Greek philosophers, Pythagoras and Plato, talked about the harmony of the spheres more than two thousand years ago. Good music was thought to be a representation of this universal harmony, while bad music, enjoyable as it may have been, leads to muggings and gang wars.the Greeks thought, control music and one controls mankind, but, you see, there is no way to control music or mankind. Lechers and politicians will use music to further their own ends, just as ethnomusicologists do when they seek the puritan values in music cultures. They all have their own axes to grind and no one cares for the impact of the resonance of grinding axes in the universe. But here, in the remote of the wilds, the interference caused by the grinding axes of pressure groups affects us not one bit and leaves us room to gloat and emote on our freedom to experience the clarity of visions of the past and the future."

Swamiji, with his usual perspicacity has hit upon what is one of the most con

tentious issues in ethnomusicology, namely its definition and its content. It is still fashionable to include the word culture in definitions of ethnomusicology, even though the word culture is now being questioned by many scholars. Music in Culture or Music as Culture both seem to exclude the study of music as music.

Incidentally, I too, have been guilty of using culture in my definition of ethnomusicology. My definition was, the study of culture in music. By that I meant that if music is an expression of culture, we should be able to find elements of culture in the music. This would involve, perhaps in the first place, the study of the music itself and then what was unique in it. That, in my opinion, was the contribution of the culture. Here I envisaged culture as the totality of group beliefs, institutions, arts, etc., as well as those of individuals, so that in one instance the music might be seen as illuminating the aesthetic values of a group or an individual, and in another, how the creators perceived their relationship to their environment, deities, etc...

But now I think that we must begin to look at our field in a different light. Musics of various world areas are becoming international commodities, or perhaps have always been so. And where does culture fit into this? Not at all. Culture is discarded as though it were unnecessary baggage, proving to me at least that the culture that created a specific form of music does not remain its owner forever. Music is much easier to appropriate and comprehend than the cultural package in which it is wrapped, and once the wrappings are removed the music takes on new meanings and becomes accessible to new audiences. Potentially this is disastrous for those ethnomusicologists who regard culture as an inseparable part of music. The handwriting has been on the wall since the early sixties when performance groups, especially Indonesian gamelans at UCLA composed mostly of American students, began making passable imitations of Indonesian music. Maybe those early efforts did not sound quite authentic, but since then, there has been plenty of proof that outsiders can make music that even insiders find convincing. The most prominent example I can quote is that of the late Jon Higgins who excelled in singing Carnatic music with such feeling that it brought tears to the eyes of South Indian listeners. And that is by no means an isolated occurrence. Twenty or more of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan's American students have achieved soloist status here and in India—and there are many others from the US and other countries who have achieved the same credibility.

As ethnomusicologists I feel we must recognize and accept this phenomenon of music isolated from its cultural element, or we shall find ourselves becoming the

archeologists of music, living in the memories of the past when music was functional and was a reflection of culture. We should be cognizant of the fact that many, if not all, types of music have the potential of leaving the community which invented it behind and establishing themselves on an international scale, as Western art music, jazz, pop, Indian music, Latin American rhythms and other forms have already done. These know no cultural bounds and in the final analysis, it is often music that persists, even when the culture of its origin dissipates or degenerates. Dynasties rise and fall, but the music survives, perhaps in a slightly modified form, but it is basically resistant to political and economic storms.

No musicology! Such a denial seems to me to undermine our whole existence. I feel, as Charles Seeger did, that we are musicologists in the first place, and if culture is a factor in order to understand a form of music, or at least its beginnings, we naturally study it. But to limit ourselves to the cultural elements seems to me like a losing cause, especially as new culturally independent musics are constantly being created through fusions, which I see as reflecting the unconscious desire of humans of different backgrounds to communicate with each other.

I believe that we must keep in mind the fact that things are continually changing, sometimes drastically, but always also consistently, just as we do in the process of aging. Evolution, and I mean this in the general sense of change, not in the biological sense, is inescapable, even though we may temporarily retard its progress through rigorous training, as in the case of Indian classical music, or by musical notations in Western music. In spite of these attempts to resist change, music continues to evolve, if only imperceptibly. We may know the notes of a particular composition in Western art music, but the interpretation of those notes changes from one generation to another. It seems as though every element in nature has potential energy which prevents it from ever achieving a completely stable or perfect state. In music, the obvious example is the diabolus in musica, the tritone, the inescapable imperfect interval which has been the driving force behind much of mankind's musical creations.

In my book, The Rags of North Indian Music: Their Structure and Evolution, which has recently been republished with an additional chapter, after being out of print for about twenty years, I have given evidence to substantiate gradual evolution in Indian music and to explain it in a systematic manner (Jairazbhoy 1971). I have also attempted to suggest how this gradual change can take place without it seeming like change. This is analogous to the human life process where individuals change from day to day as they age imperceptibly, and still maintain their identity, as I hope came through in our video.

Evolution of music is not unlike evolution in other areas, proceeding, in general, from the simpler to the more complex. In the arts this can be described as the growth of human cognition, that is, the consonances we accept today will tomorrow become mundane and boring and some of the dissonances of today will become the new consonances of tomorrow. In my book on rags, I draw attention to the underpinnings of Indian music, the perception of tetrachordal symmetries which provide a grammatical structure to the music. This is in some ways analogous to the grammar of Western music's Common Practice Harmony which was also derived after the fact. Just as in the West the grammar of CPH has been far exceeded and even superseded by atonality, so in Indian music the grammatical base of simple tetrachordal symmetries has been expanded by the cognition of complex symmetries and perhaps even asymmetry.

Everything is changing and growing, and although we all comprehend this, many of us unwittingly attempt to mold others in our image. Instead, it might be more rewarding if we were more receptive to being molded by our students, especially as they come from so many diverse backgrounds. We should, I feel, encourage difference, introduce true multiculturalism in our thinking and not attempt to indoctrinate others to our ways of thought about scholarship which will undoubtedly be challenged tomorrow, when the pendulum reverses its swing.

1. Cerroni-Long, E. L. 1995. "Introduction: Insider or Native Anthropology?" NAPA Bulletin 16:7.

Catlin-Jairazbhoy, Amy. 1995. An Alphabetical Autobiography of Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy: From A to F. Unpublished video.

Jairazbhoy, Nazir Ali. 1971. The Rags of North Indian Music: Their Structure and Evolution. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. [Reprinted with new introduction by Popular Prakashan, Bombay, 1995. CD examples by Ustad Vilayat Khan and Ustad Umrao Bundu Khan can be obtained from Apsara Media, 13659 Victory Blvd., Suite 577, Van Nuys, CA,91401.]

———. 1991. Hi-Tech Shiva and Other Apocryphal Stories: An Academic Allegory. Van Nuys, CA: Apsara Media.