(Re)Locating Flamenco: A Northern California Case Study

Winner of the Marnie Dilling Prize for best student paper at the 2010 conference of the Northern California Chapter of the Society for Ethnomusicology (NCCSEM)

In the North Beach district of San Francisco, in an Italian neighborhood just blocks away from Chinatown, there stands a landmark building best known as the Old Spaghetti Factory. Today it houses the Bocci restaurant, but in the late 1950s it was home to Los Flamencos de la Bodega, a small group of bohemians, beatniks, and flamenco artists who congregated and performed weekly in a room that sat no more than forty people.1 For nearly thirty years, these local artists offered patrons a glimpse of the exotic and helped to establish a social network that now supports a large and diverse domestic flamenco culture. Through a variety of flamenco styles, from the unadorned to the theatrical, Los Flamencos de la Bodega left a legacy that is at once rooted in flamenco folklore yet is expressive of northern Californian cosmopolitanism.

North Beach, San Francisco

View Larger Map

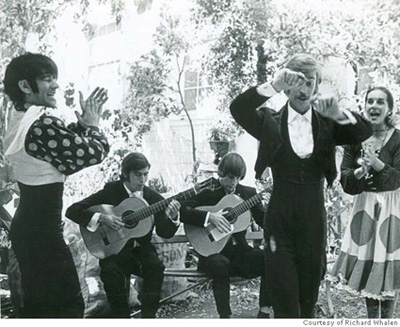

Dancing in the courtyard of the Old Spaghetti Factory. Ernesto Hernandez (left), David Jones (a.k.a. David Serva) (center), Isa Mura (right), unknown guitarists. Photo used by permission.

In their construction of a flamenco identity, local performers and aficionados creatively deploy metaphors of purity, passion, and essentialism. Some focus on an idealized simplicity projected upon the impoverished rural Gitanos of Andalusia, seeing this as the natural beginning and ending of pure flamenco. For others, the spirit of flamenco does not die with the passing of its eldest practitioner but lives in the artists’ ability to communicate its emotional contagion. For others still, flamenco is but one part of the musical equation of life; significant on its own but able to achieve greater power when combined with other expressive arts. These diverse, often contentious perspectives guide the various styles of flamenco in northern California, which I categorize as Purists, Modernists, and Fusionists.2 The motivating forces behind their stylistic (and ideological) differences provide a model for understanding flamenco’s diversity as a globally popular genre.

Purists: Embodying a Lifestyle

Just as North Beach was the center of the Beat movement, The Old Spaghetti Factory became a vital meeting and performance space for a bohemian lifestyle. Artistically anti-establishment, the Beats rejected overt materialism and hegemonic heterosexuality. Writers, both foreign and domestic, expressed an affinity for rural Andalusian Gitano lifestyle. The poetry of Spain’s Federico Garcia Lorca,3 which routinely valorized primitivism and projected it upon flamenco and Andalusia, resonated with a generation of California artists who were disillusioned by what they perceived as America’s increasing greed and materialism. Rural Andalusia, specifically the town of Morón de la Frontera becamea Mecca for many California artists and the Gitano lifestyle likewise became a symbolic antidote for America’s ailing morality.4

Morón de la Frontera

View Larger Map

In the early 1960s, American author and flamenco aficionado Don Pohren purchased a farmhouse in Morón and opened it to foreigners who wanted to experience pueblo-style flamenco.5 There, at Finca Espartero, idealistic American artists found the quaint lifestyle and honest performance aesthetic they were searching for. Conversely, Morón’s locals were introduced to waves of foreign tourists, arriving on the eve of America’s sexual revolution. Berkeley, CA native, Mica Graña, remembers this clash of cultures:

[Fitting in] meant not looking at the boys, essentially, and keeping our skirts below our knees and our legs crossed. Jill [Snow] and I dressed like the most dowdy housewives. We came in as hippies but I learned within a week that if I wanted to begin to fit in, I needed to get rid of my bell-bottomed pants and halter tops. We started dressing like these matronly housewives because you have more freedom that way... Just sort of following the social mores that were around you. (Personal communication, Graña 2009)6

Mica Graña standing next to a poster of Diego del Gastor in Berkeley, CA. Photo by Tony Dumas.

Mica and Jill found local acceptance when the Gitano butcher and singer Anzonini del Puerto became their local chaperone:

[It was] like “Anzonini's Finishing School for Young Ladies.” The result was if it hadn't been for him, we wouldn't have gotten into anything really because first of all, women didn't hang out in bars. Women didn't go to fiestas unless…it was a family thing or they were actual performers. But we were safe because we had [Anzonini] so then their Gypsy boys were protected from us, presumably, because they weren't going to let these foreign women, you know…and of course as soon as we started being around the music we had no desire to mess with the boys because we would have blown our chances to be around this fabulous music. (Personal communication, Graña 2009)

Many were drawn to Morón’s patriarchal guitarist, Diego del Gastor, who “possessed a trait much admired by the gypsies at the time: a complete disregard, even scorn, for money and material possessions” (Pohren 1979:22). They found Diego’s chaste style to be a refreshing alternative to American excess and were attracted to his unadorned performance aesthetic that seemed to parallel Morón’s quaint lifestyle. As one Berkeley dancer puts it: “without doing anything, they say so much” (Personal communication, Ayala 2009).

One guitarist in particular, David Jones, a.k.a., David Serva, became Diego’s most celebrated protégé,7 assimilating the Morón style so faithfully that Diego concluded that Serva must be “an American Gypsy” (Nagin 2000:5).8 Bringing Morón’s straightforward style with him, Serva returned to San Francisco in the mid 1960s and quickly became a local folk hero. Through his stories and playing he inspired at least two generations of guitarists and dancers to make regular pilgrimages to Morón and conveyed an aura of purity that contrasted with the more theatrical performances that were common at the time (Personal communication, Paul Shalmy, 2009). Here’s an example of the Morón style as played by Diego del Gastor.

Musical Example: Diego’s Morón style

In this example, Diego del Gastor plays a bulerias. The structure of bulerias as shown has a major tonic (with an added flat-9th) moving to a major chord a half-step higher on beat 3. That tension resolves back to the altered tonic on beat 10. Notice that Diego stays on that tonic chord throughout while punctuating the 12-count accent pattern (3+3+2+2+2) rhythmically and by adding the Bb (b9) to the tonic. Diego’s minimalism respects the driving rhythm and static harmony as if to say “this is all you need.”

Modern Flamenco: Deterritorialized and Dualistic

Whereas Serva’s playing channels the pueblo-style of Morón, the so-called “modern” style is “unmoored,” in the words of local aficionado Paul Shalmy—that is, it lacks a specific regional association, referencing many regional styles as one.9 Shalmy’s undestanding centers on the widespread influence of guitarist Paco de Lucia, an icon in both jazz and flamenco. Paco de Lucia grew up in Algeciras, a busy port town at the southern tip of Spain, which, according to Shalmy, lacked a strongly-defined local flamenco style of its own. In Shalmy’s words:

Everyone hears compás (rhythm) differently. In Jerez they do it one way and in Sevilla they do it another way...and on and on. So each of these places had its own distinct sello (stamp) [that was] passed down from one generation to the next...giving a certain kind of cohesiveness to the toque (guitar), the baile (dance), and the cante (singing) of those pueblos. Paco de Lucia, I never felt had that. [Instead], he put together a toque [i.e., way of playing the guitar] that was unmoored [and] it has become the sound of modern flamenco. (Personal communication, Shalmy 2009)

A look back in time reveals another condition of modern flamenco: ironic dualism, i.e., a performance style that is at once fixed and improvised. Flamenco’s move to the stage in the 1840s increased its level of musical fixity in terms of choreographed dances and reproducible song-like structures.10 Conventionally, flamenco music consists of traditional lyrics chosen at random by the singer and sung to one of many distinct rhythmic and harmonic forms (e.g., bulerias, solea, seguiriya, etc.). As Peter Manuel (2010) illustrates, improvised flamenco defies the standard definition of a musical “work.” However, as a staged genre, flamenco has another side that moves closer to being a reproducible work, fueling polemic debates among connoisseurs. For some, flamenco as a commercial commodity is incompatible with flamenco as an improvised way of life. Others, however, accept that flamenco has a dual nature: both fixed and improvised—two sides of the same coin.

Yaelisa, an Emmy-winning choreographer and the artistic director of Caminos Flamenco embraces this ironic duality.11 Performing regularly in large theaters and in small clubs, Yaelisa12 retains flamenco’s improvisational quality, even within the context of a highly choreographed dance:

With the really younger generation, they’re forgetting the roots of flamenco. They’re going out and doing a solo that has no improvisation, or if it does, it’s too thought out. Flamenco has to have an element of improvisation. If it doesn’t, it starts to lose its spark. It never was intended to be choreographed from beginning to end... there’s a kind of energy when the choreography is not a known commodity. (Yaelisa qtd in Pasles 2001)

Yaelisa dancing at floor level and in close proximity to the audience. The performance lacks stage lighting and uses a minimal sound system. Photo taken by Tony Dumas. Location: The Verdi Club in San Francisco.

Keeping with this, it is common practice for Caminos Flamenco’s musical director, guitarist Jason McGuire,13 to meet briefly, if at all, with the company’s dancers before a show. With fresh eyes and ears, McGuire’s virtuosic accompaniments are largely improvised as a dance unfolds, forcing a fresh perspective of even the most thoroughly choreographed phrase. The elements of his unmoored style are drawn from flamenco, jazz, rock, heavy metal, and Latin American guitar styles, comprising an eclectic and complex “bag of tricks.”

Musical Example: Modern Guitar Style

The following video shows McGuire playing a bulerias, the same form we saw earlier but unlike the simplicity of Diego’s pueblo style, McGuire’s busier style seems to reflect his cosmopolitan lifestyle. In contrast to Diego’s style, McGuire’s is more harmonically active and uses more timbral variations than Diego and a larger variety of chord voicings.

The bulerias rhythm starts at 0:55

Fusionists: Bridging Cultural and Musical Chasms

A third style of flamenco exists in Northern California, one that fuses flamenco with other genres such as jazz, heavy metal, Cuban Son, etc. These performers are motivated to musically highlight points of unity between disparate cultures. One local composer Chus Alonso explains:

As a composer, the power of music to bring cultures together has always been of interest to me. In a highly interconnected world -- where lack of understanding between people of different cultural backgrounds often gives rise to conflict –- composers, I believe, have an important role to play in building bridges between traditions, cultures, sensitivities, and aesthetics. (Personal communication, Alonso 2010)

Chus Alonso in his home studio in Albany, CA. Photo taken by Tony Dumas.

Alonso is the director and principle composer for Potaje, a band that blends flamenco with Cuban music and contemporary jazz. Married to an American, Alonso is from a small village in West-central Spain (Castile) whose inhabitants have strong ties to Cuba. Asserting a natural affinity toward bridging cultures, Alonso grew up playing and listening to Spanish and Cuban folk music, flamenco, classical music, and jazz (personal communication, Alonso 2009).

Alonso looks to flamenco’s characteristic Phrygian modality as bridge-building material. He writes:

The Spanish composer Manuel de Falla reminded us that by restricting our music to two series, the major and minor modes, Western music [built] a border that separates us from the whole Eastern world and many other cultures. In that respect, flamenco is a West-East connecting bridge. ("Latin-Flamenco Rhythm Workshop" 2009)14

Compositionally, the flamenco-phrygian mode offers Alonso two alternatives to Western tonal practices. First, is its inherent duality (i.e., implying both major and minor modalities) and second, its alternative to tonic/dominant structures. Although the phrygian mode, by virtue of its minor third scale degree, is minor, the convention in flamenco is to resolve its characteristic Andalusian cadence, seen below, to the major tonic, creating a curious relation between the root of the III chord (G B D) and the third of the I chord (E G# B). Further, in flamenco, the major triad, built one half step above the tonic, serves a dominant function [see slide].

Modality is one channel through which Alonso conceptually bridges cultures, another is musical structure. Alonso explains:

In Cuban music, [in] the section where improvisation happens, the montuno section, there is a vamp of often just two chords: tonic and dominant. This harmonic wave, together with a polyrhythmic background, creates the “groove.” In many of my flamenco-rooted compositions where there is an improvised section I combine this concept of “groove” with flamenco sounds and rhythms. Instead of using tonic and dominant chords in a major or minor key, I use a flamenco phrygian mode with a “major flat nine” chord [“E(b9)”, for instance] as the tonic chord, and a major chord situated half step above the tonic (“F”). This chord it is not, strictly speaking, the dominant chord, but it does have a similar function in this context.15 If the style of the piece is bulerias, I would respect the natural resolution of the bulerias; which goes off on “3” and comes back to tonic on “10” (assuming you count bulerias like: 12, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). (Personal communication, Alonso 2009)

Musical Example: Flamenco Fusion

In this example, Alonso begins with an introduction of a phrygian melody in which the flute imitates guitar arpeggios on each note.16 The melody enters to the form of bulerias. As typical in jazz, after the melody is played, performers improvise over a set chord progression: here, it’s Am, G, F, E (Andalusian Cadence).

The contrast between flamenco and jazz lies partly in the interaction between the improvisor and accompanist. It is typical in flamenco for the guitarist to support the singer, to harmonically and rhythmically anticipate their improvisation. Conversely, improvising over a montuno or vamp section relies on the consistency of a set accompaniment pattern.

When I play with a flamenco guitarist who is not used to Latin music I have to be very clear explaining how to play an improvised montuno section. The natural tendency of a flamenco guitarist is to follow the soloist harmonically and try to anticipate where he or she is going. In contrast with this, the montuno section stays constant on the same vamp in a very reliable and consistent way. The improviser uses this to build their improvisation. When the improviser goes off to “foreign” notes, their intention is not to move into a different harmonic progression but simply to build harmonic tensions. If however, you try to follow me, then I try to follow you, then we go no where. (Personal communication, Alonso 2009/2010)

And where Alonso wants to go is not always back to the pueblo of the Purist’s folklore. Rather, he wants to explore a wider musical landscape where identity is bound not to a single location or lifestyle but where it reflects a vastly diverse, and at times contradicting, cosmopolitanism.

The three styles of flamenco presented here reflect different concepts concerning what flamenco is and how it can be used. For the Purists, flamenco is intimately tied to a very particular lifestyle, one that is all but lost to the modern world. Nostalgia and vigorous adherence to a simple and driving performance aesthetic help keep the Morón-style alive. The Modernists, however, embrace wider musical influences while remaining grounded in the concept of deep artistic expression through improvisation. For the Fusionists, artistic expression turns to humanistic expression that blends its flamenco voice with a chorus of other voices. In the end, there is no single flamenco style, rather an understanding that flamenco is the interaction of all three styles, what they share, and how they represent different ways of thinking about the world.

1. The room was called Las Cuevas, the caves. Los Flamencos de la Bodega would perform four nights a week (Wednesday through Saturday) and sometimes a fifth (Sunday). The modest door charge was split to pay the performers.

2. Note that these are my working categories as I conduct this fieldwork and not that of the actual participants.

3. The 1922 Concurso de Cante Jondo, directed by Lorca and Manuel de Falla “[a]ttempts to establish something ‘essentially Spanish’ in deep song, something worth saving from the pillage of commercialism” (Simpson 2007: 77). Melanie Simpson’s dissertation illustrates how “Lorca's positive, even rhapsodic approach to the primitive nature of cante jondo suggests an attempt to recast the “backward” Spanish pueblo as a sort of dark ideal that despite its struggles preserves an authentic version of humanity untainted by European (Western) progress” (ibid.).

4. A tax that prohibited tourism was repealed in 1959 (Hooper 2006:17).

5. Pohren bought the finca from a renowned Californian bohemian painter, Judith Diem, who was the grandmother of California flamenco dancer, La Tania.

6. Daughter of Berkeley sociologist Cesar Graña, Mica went to Morón during the throes of America’s cultural revolution in the mid 1960s. Jill Snow is the former American wife of the Spanish flamenco guitarist Pedro Bacán.

7. Serva is the Caló word for Seville. Jones, who now lives in Madrid, adopted “Serva” as a stage name early in his career.

8. Serva was however, from the Midwestern United States.

9. Paul Shalmy, a retired journalist, magazine editor, and longtime flamenco aficionado, is also the brother-in-law of David “Serva” Jones. Shalmy is the author of, El Cante Flamenco: A Guide for the Perplexed (1992), and one of three Americans to speak at the 2008 International Congress of Diego del Gastor. The other two were Serva and Jill Snow.

10. The first cafe cantante opened in Sevilla in 1842.

11. Perhaps it is better understood as a split personality in a shared body, each with its own purpose and style.

12. She is the daughter of Spaghetti Factory singer and dancer, Isa Mura.

13. McGuire was the recipient of the 1987 Downbeat “Dee-Bee” award in Jazz.

14. On the official website describing his Latin-Flamenco workshops held at San Francisco’s Community Music Center.

15. This harmonic shift resembles a Neapolitan-like movement but functions like dominant, not predominant.

16. This example is Zorongo, a melody popularized by Garcia Lorca.

Alonso, Chus. 2009. Interview with the author. Albany, CA, July 12.

———. 2010. Interview. Albany, CA, January 2.

Ayala, Sara. 2009. Interview with the author. Berkeley, CA, July 16.

“Bulerias Diego del Gastor.” latinosomos. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W74IVr_90CQ (Accessed February 1, 2010).

Graña, Mica. 2009. Interview with the author. Berkeley, CA, July 21.

Hooper, John. 2006. The New Spaniards. Second edition. London: Penguin Books.

“Latin-Flamenco Rhythm Workshop.” 2009. Chus Alonso:Potaje. http://chus.carayanpress.com/latflamwrkshop.html (Accessed September 22).

Manuel, Peter. 2010. “Composition, Authorship, and Ownership in Flamenco, Past and Present.” Ethnomusicology 54(1):106-135.

Nagin, Carl. 2000. “The Ballad of Gypsy Davy.” East Bay Express, March 10.

“Paisaje Jerezano(Bulerias)-Jason McGuire.” http://vids.myspace.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=vids.individual&videoid=1598668 (Accessed February 1, 2010).

Pasles, Chris. 2001. “Flamenco’s Next Step.” Los Angeles Times, August 9.

Pohren, D. E. 1980. A Way of Life. Madrid: Society of Spanish Studies.

Shalmy, Paul. 1992. “El Cante Flamenco: A Guide for the Perplexed.” The World & I (September):624-637.

———. 2009. Interview with the author. Berkeley, CA, July 21.

Simpson, Melanie Catherine. 2007. “The Persistence of Difference: Mythologies of Essentialism, the Anglophone World and Modern Spanish Cultural Identity.” Ph.D. dissertation, Stony Brook University.

“The Mark Taylor Flamenco Quartet, Zorongo.” The Mark Taylor Flamenco Quartet. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v= VHBE3UaN-4o (Accessed February 1, 2010).