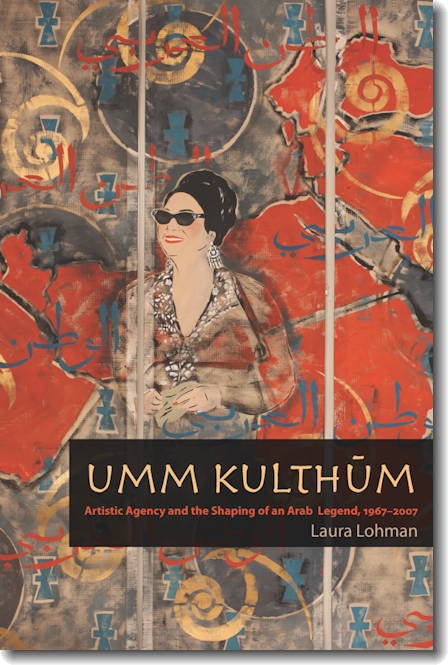

Umm Kulthum: Artistic Agency and the Shaping of an Arab Legend, 1967–2007

Solo female singers of renown––often referred to as “divas”––can be important in forming an emotional connection between people and place. They often become a part of social and political boundaries and perceptions of “self.” As Fairuz is to Lebanon and Piaf is to Paris, Umm Kulthūm (1898-1975) remains the definitive Egyptian diva, and is a figure with which proceeding female singers were compared and many still try to emulate. The status of this diva was heightened by the breadth of her popularity, her powerful emotional effect on followers, the embodiment of personal or political hopes and aspirations, and a continued “presence” even after death. Her legacy continues to generate analysis and interpretation, and Laura Lohman’s Umm Kulthūm is a contribution to the continuing discussion.

The book explores discourses regarding Umm Kulthūm’s public persona and legacy. Lohman presents issues from Kulthūm’s lifetime, discussing the singer’s continued place in Egyptian cultural life and throughout the Arabic-speaking and Islamic world. This work looks at the singer’s life and legacy within a context of government agendas, Israeli-Egyptian conflicts, and pan-Arab nationalism. In each chapter, Lohman takes into account how the singer strategized her public image, how her activities were interpreted by fans and critics, and for what purposes her image was used and continues to be invoked.

The book is divided into six chapters, plus introduction and epilogue. The first chapter, “A New Umm Kulthūm,” begins a discussion of the late stages Kulthūm’s career, which coincided with the rule of President Jamāl 'Abd al-Nāṣir. The chapter pays particular attention to the singer’s place in the Egyptian public imagination during tension and conflict with Israel in the 1950s, and 1960s. The author references repertoire examples, favorable media coverage, and performances that bolstered enthusiasm for Egypt within the country, even after military failure and amid public discontent with Nāṣir.

In the second chapter “For Country or Self?” Lohman continues to consider Egyptian anxiety over Israeli, and she interprets Kulthūm’s pro-Arab and pro-Egyptian sentiment as a way of keeping in her government’s good graces and thereby winning positive media reviews and staying in the spotlight. Broadening the circle of engagement, the author presents examples of Kulthūm’s performances and activities throughout the Levant and Maghreb, and further eastward into the Arab peninsula, Iraq, and Pakistan. In performance (for the concert hall audience or for the media), the singer portrayed language, dialect, song form, and maqams as “shared” cultural traits across culturally diverse regions. By invoking shared characteristics, Kulthūm emphasized a notion of shared heritage among her audiences and in doing so became a symbolic figure who embodied cultural and emotional unity between Arabic-speaking and Islamic peoples.

Chapter 3, “Sustaining a Career, Shaping a Legacy,” focuses on Kulthūm’s activities from the late 1960s until her death in 1971. Lohman covers self-crafted “faces” of Kulthūm’s public image: her emphasis on rural roots, portrayal as a loyal daughter, a woman with strong maternal instincts, a humanitarian, and a supporter of war efforts. Lohman argues that these images were bolstered by media reports during ongoing international engagements, and the author interprets the images as strategic in order to showcase “political currency and cultural relevance across the region for listeners at home” (87). Lohman argues that it was this late stage of Kulthūm’s career that shaped her posthumous legacy.

Chapter 4, “From Artist to Legend” traces the evolution of Kulthūm’s image from village girl to to emotional and mythical symbol of “the nation.” Looking at the social and political role of the singer even after death, Lohman illustrates how the singer’s place was secured in the emotional life of “the nation,” thanks to her appeal to people from all classes and political persuasions.

The fifth chapter, “Mother of Egypt or Erotic Partner?” addresses perceived sexuality that was, and is, projected by audiences and proposed by critics. Several options (and various combinations of each option) existed during her lifetime, including: the object of desire, mediator of desire, homosexual, bisexual, maternal figure, sexually ambiguous, asexual, and/or beyond sexuality. Reasoning behind interpretations varied and was often related to support or criticism of Kulthūm’s personal and political life. Factors which informed such varied perceptions included anomalous aspects of her life as a woman functioning in a high-profile occupation, her late and childless marriage, and expected gendered behavior in Egyptian society. The singer promoted a maternal public image as a woman who caressed babies and infants, as well as a mother of Egypt, the Arab world, and the Islamic world. Still, as somewhat of an anomaly, her private life was a target of scrutiny.

After her death, fans and supporters promoted her patriotism and feminine virtues while down-playing still unsubstantiated rumors of “deviant” sexual behavior. In the final analysis, Lohman interprets sustained “competing interpretations” of Kulthūm’s sexuality as yet another sign of her significant presence in the region (136). “An Evolving Heritage,” the last chapter, scrutinizes print, film, and art in which Kulthūm is a central figure. The discussion then extends to public monuments, establishments such as restaurants and cafes, and museums.

At several points in the book, Lohman references Virginia Danielson’s award winning The Voice of Egypt, but avoids significant cross-over with Danielson’s work thanks to a deep engagement with media sources, concern with a wide geography, and emphasis on continued legacy. The book is enriched with excerpts from media coverage from across the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe. High quality photographs add vibrancy to the narratives, and musical transcriptions appear interspersed throughout the body of the text in order to help illustrate musical concepts mentioned in the text. In addition to being of interest to music scholars, Umm Kulthūm will be of importance to anyone interested in contemporary Egyptian cultural history and pan-Arab nationalism. Lohman’s timely work can bring historical perspective to readers who explore questions of individual creativity, or the place of media in Egyptian political life.

This is Laura Lohman’s first book. She is a professor in the Department of Music at California State University, Fullerton.