Lo Nuestro es lo Verdadero: The Rise of Alí-Babá at Dominican Carnival

On 27 January 2010, the Dominican National Brewery, in conjunction with the Dominican Ministry of Culture, launched the cultural campaign and advertisement slogan "Lo nuestro es lo verdadero" at the official opening of the Dominican Carnival season. Roughly translating into English as "What’s ours is what’s real," the Brewery unveiled its marketing strategy with its flagship brand Presidente Beer as the official sponsor of Dominican carnivals, folklore, and traditions.

On 27 January 2010, the Dominican National Brewery, in conjunction with the Dominican Ministry of Culture, launched the cultural campaign and advertisement slogan "Lo nuestro es lo verdadero" at the official opening of the Dominican Carnival season. Roughly translating into English as "What’s ours is what’s real," the Brewery unveiled its marketing strategy with its flagship brand Presidente Beer as the official sponsor of Dominican carnivals, folklore, and traditions.

According to Presidente brand-manager Marisol Martinéz, quoted in an article published in the online periodical DominicanosHoy.com, "Presidente always supports what is Dominican ('lo dominicano') and what is real ('lo verdadero'), which shows that at the exact moment of saying Carnival, one must speak of Presidente" (2010). In this paper, I explore the convergence of "lo verdadero" and "lo dominicano" as it pertains to the rise of carnival dance/music groups (comparsas) known as Alí-Babá. In the following sections, I analyze the carnival activities directed by the Dominican state (including both government agencies and affiliated cultural organizations) and those of the Dominican populace during the celebration of the National Carnival parade in Santo Domingo. In conclusion, I will demonstrate that Alí-Babá may be the ideal representation of "lo verdadero dominicano"—representing a bridge between fiercely independent regional carnival traditions and potentially reconciling decades of racialized Dominican cultural politics.

In 1982, a group of Dominican scholars in conjunction with the Secretary of State of Tourism (now the Ministry of Tourism) conceived of the idea to create a "national" carnival celebration to be held in the city of Santo Domingo (Tejeda Ortiz 2008:129). The National Parade was designed to showcase the best of the various regional carnivals at one time, in one place. In 1983, the Dominican state laid the groundwork for the National Parade (separate from many diverse local carnival celebrations), designated competition categories, and commissioned a merengue composition for the centerpiece of each year’s festivities. The first merengue to be commissioned for National Carnival was Luis Días's "Baila en la Calle," initially recorded by Días for the parade in 1984 (see Video 1) and rerecorded and made famous by mega-star Fernando Villalona in 1986. Both subsequent music videos accompanying the carnival anthems feature the artists (Días and Sonia Silvestre in the 1984 version and Fernando Villalona in the 1986 version) and glimpses of typical Dominican carnival comparsas parading along the Malecón in Santo Domingo.

Video 1: Luís Días "Baila en la Calle" (1984). Source: YouTube

“En el carnaval, baila en la calle de día, | “During carnival, dance in the street all day, |

Today, "Baila en la Calle" is still heard throughout the carnival season in the Dominican Republic. This is thanks in part to its release on the Ministry of Tourism’s 2006 CD Dominican Carnival and also to the ever-present "disco lights," or giant trucks carrying oversized speakers. However, no other merengue commissioned for the National Parade has enjoyed such acclaim and, in fact, the state stopped commissioning new carnival merengues altogether in 2005.

Figure 2: “Disco light” truck.

In addition to the National Parade, the four regions of Santo Domingo also host independent local carnival celebrations throughout the month of February. During the early decades of the nascent National Parade while the Dominican state was actively commissioning merengues, something else was happening within the Villa Francisca barrio in the capital’s Federal District.  According to legend, sometime in the early 1980s Luis Roberto Torres or "Chachón" (left), then a young choreographer, was in desperate need of an impressive new costume in order to win a salsa-dancing competition. As luck would have it, being carnival season, a marching band passed outside his house at the exact moment Chachón’s mother came into the living room with a towel wrapped around her head. He was then inspired to create the oriental-themed Alí-Babá costume and subsequent dance (Tejeda Ortiz 2008:219). Rather quickly, Chachón organized a carnival group, whose members were loosely dressed like the character Ali Baba, and were also accompanied by a marching percussion ensemble. Interestingly enough, Chachón’s Alí-Babá comparsa can even be spotted briefly within the music video of Días's original 1984 recording of "Baila en la Calle" (see Video 1). In the very first National Carnival, Chachón’s Alí-Babá comparsa tied for first place in the "fantasy" category along with the more established and commercialized comparsa of diablos cojuelos (or masked devil characters) from La Vega (Tejeda Ortiz 2010:21). Other Alí-Babá groups formed soon after and as the popularity of these groups grew, carnival organizers were compelled to create a new, separate competitive prize category for the Alí-Babás (see Desfile Nacional 2009). The year 2009 was particularly exceptional for Chachón, as he was awarded the annual Felipe Abreu National Carnival Prize—"the highest distinction given by the Dominican State to a carnival participant" (Desfile 2009:11). Since 2009, comparsas competing in the Alí-Babá category have represented at least 5% of the total and no longer limit themselves to "oriental"-themed costumes (Damirón 2009).

According to legend, sometime in the early 1980s Luis Roberto Torres or "Chachón" (left), then a young choreographer, was in desperate need of an impressive new costume in order to win a salsa-dancing competition. As luck would have it, being carnival season, a marching band passed outside his house at the exact moment Chachón’s mother came into the living room with a towel wrapped around her head. He was then inspired to create the oriental-themed Alí-Babá costume and subsequent dance (Tejeda Ortiz 2008:219). Rather quickly, Chachón organized a carnival group, whose members were loosely dressed like the character Ali Baba, and were also accompanied by a marching percussion ensemble. Interestingly enough, Chachón’s Alí-Babá comparsa can even be spotted briefly within the music video of Días's original 1984 recording of "Baila en la Calle" (see Video 1). In the very first National Carnival, Chachón’s Alí-Babá comparsa tied for first place in the "fantasy" category along with the more established and commercialized comparsa of diablos cojuelos (or masked devil characters) from La Vega (Tejeda Ortiz 2010:21). Other Alí-Babá groups formed soon after and as the popularity of these groups grew, carnival organizers were compelled to create a new, separate competitive prize category for the Alí-Babás (see Desfile Nacional 2009). The year 2009 was particularly exceptional for Chachón, as he was awarded the annual Felipe Abreu National Carnival Prize—"the highest distinction given by the Dominican State to a carnival participant" (Desfile 2009:11). Since 2009, comparsas competing in the Alí-Babá category have represented at least 5% of the total and no longer limit themselves to "oriental"-themed costumes (Damirón 2009).

Today, Alí-Babá remains an expression of the street, yet mixes equal parts of popular carnival traditions, prestigious costumes, and choreographed footwork. Although Alí-Babá music and dance enjoy exponentially increasing success and prominence at Dominican National Carnival every year, I argue that the genre's late emergence (relative to carnival music traditions such as samba in Rio de Janeiro in the 1930s) is a result of the Dominican Republic’s racialized political history. In the next section, I discuss Dominican cultural politics, with a particular emphasis on the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo and his successors (from the 1930s to the 1980s), in order to understand the relationship between cultural politics and contemporary carnival music practices in the Dominican Republic.

Like other Latin American dictators, Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo realized the power of popular cultural expressions to act as national emblems and bolster popular support for his regime. However, unlike his contemporaries such as Getulio Vargas in Brazil, Trujillo never had any official policy that attempted to integrate Afro-Dominicans into elite carnival practices in Santo Domingo. During his autocratic rule (1931–1960), Trujillo’s racist cultural policies promoted a state-generated "Dominican" national identity positioned as white, Spanish, and Catholic (Morrison 2009:61). Although Trujillo forcibly isolated and suppressed the many Afro-Dominican and Haitian populations within the Dominican Republic, he failed to eradicate the development and performance of their cultural expressions.

After half a decade of racialized cultural campaigns championed by Trujillo and continued by his successor Joaquin Balaguer, the 1980s saw the first shift to populist cultural politics and the rise of academic interest in Afro-Dominican cultural expressions. The work of Dominican scholars like Fradique Lizardo (1974, 1979) and Julio César Mota (1977), and American scholars like Martha Davis (1976, 1981, 1987) and June Rosenberg (1979), resulted in a national awareness of African musical and cultural heritage in the Dominican Republic, including a particular interest in genres like Afro-influenced regional merengue variants, congos, palos, gagá, and the guloyas. Two of these formerly suppressed genres—gagá and the guloyas—would prove to be crucial for the genesis of Alí-Babá in the 1980s.

Gagá is a direct import of the Haitian Lenten street-celebration rara, a syncretic religious practice that mixes West African elements with Catholicism and can now be found throughout the Dominican Republic. The gagá ritual consists of songs sung in call-and-response style accompanied by dancers dressed in multi-colored raffia skirts and a percussion ensemble of single-headed palos drums, double-headed drums called tamboras, and single-note bamboo and metal trumpets called bambúes and fututos, respectively. The sound of the gagá ensemble is typified by its intense duple-meter drum rhythms and an interlocking ostinato melodic pattern performed by the bamboo and metal trumpets.

Figures 4 & 5: Gagá instruments: Bambúes (bamboo tubes), fututos (metal trumpets), palos (tall drum), tamboras (hand/stick drum).

Audio 1: “Gagá and Califé” by Victor Tolentino and Choir (2006).

The practice of guloya costumed dance-theater is found primarily in the eastern provincial town of San Pedro de Macorís. The guloyas were originally Christmas season masquerades brought by protestant black laborers imported by Trujillo from the English and Dutch Antilles (to curtail the ever growing Haitian migrant worker population) and are accompanied by a small group of musicians playing snare drum, bass drum, triangle, and ornamented by sporadic high-pitched flourishes on fife (Inoa 2005:88-90).

Figure 6: Guloya instruments: fife (metal flute), steel (triangle), redoblante (snare drum), tambor (bass drum).

Audio 2: “Danza Guloya” by Maria la O (2004).

The guloyas would have a particular influence on Alí-Babá, as it was a band of marching guloyas that passed by Chachón’s home on that fateful day. Like the guloyas, Alí-Babá is typically accompanied by its own marching band, called an "Alí-Banda," with snare and bass drums to supply the fundamental rhythm, and tambora, güira, or other percussion instruments sometimes added for support.

Figure 7: Alí-Banda instruments: redoblante, tambor, tambora (played like a snare), trompeta (metal trumpet), trombone, flute, whistle.

In general, the rhythmic groove of the Alí-Banda is more regular than the guloyas and the snare especially is less improvisatory. The melodic instruments of the Alí-Banda vary greatly between groups, but typically include fututo-like trompetas (like those utilized in gagá), sometimes with trombones, whistles, or the occasional flute.

Video 2: "Los Faraones" (February 16, 2012). Source: YouTube

However, the beginning of afro-Dominican research among scholars in the 1980s did not result in an instant change within the hearts and minds of the Dominican state or its people. As I previously mentioned, merengue was still chosen as the official music of Dominican National Carnival between 1984 and 2005—in part because it is the national dance/music of the Dominican Republic and in part because the Trujillo-era suppression of Afro-Dominican cultural expressions meant that there was not yet a rival dance/music suitable for the task. However, in 2005, a newly formed National Carnival Commission overhauled the National Carnival parade in an attempt to transform it and promote more live music performance. The results of the Commission's first National Carnival Congress, called "the springtime of Dominican identity" by Avelino Stanely, were the following: sixty-eight "accords," twenty-six "general recommendations," and eight "final resolutions" for improving National Carnival (Primer Congreso 2006:11). Some of the Commission’s decisions included "giving priority to Dominican music. . . [,] motivating comparsas to bring their own musicians . . . which in addition to fomenting musical creativity would avoid the problem of the transit of the so-called 'disco ligths' [sic]" (22, 33). This change in attitude of the Dominican state would pave the way for the ground-up surge in popularity of the Alí-Banda sound during carnival.

In 2006, the Bayahonda Foundation, a private cultural organization, re-released their CD Carnival Music, featuring the first commercial recording of Alí-Babá music aptly titled "Mambo Alí Babá," performed by Alex Boutique and his group The Kings of Carnival (Audio 3).

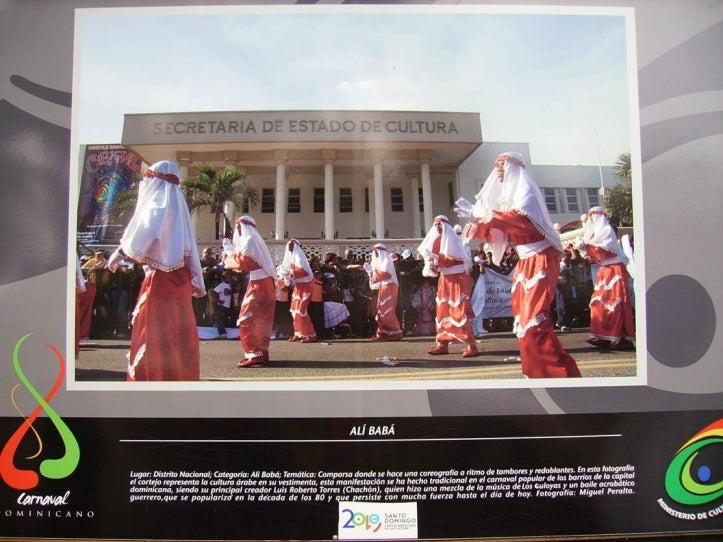

Figure 8: "Alí Babá." Photograph by Miguel Peralta

Audio 3: "Mambo Alí-Babá" The Kings of Carnaval

“Si, desde la Jacuba de Villa Francisca . . . | “Yes, from Jacuba Street in Villa Francisca |

By the 2011 carnival season, Boutique's renamed The Kings of Mambo had released several more commercial carnival mambo anthems celebrating local Dominican culture, including songs like "Motoconcho" (Dominican motorcycle taxi), "Concón" (the burnt rice that sticks to the pot), and "Cuida tu celular" (Audio 4) celebrating the art of Dominican pick-pockets. Even though the infamous "disco lights" were still all-pervading at the 2011 Dominican National Carnival Parade, most comparsas at least choose to play the now ubiquitous "Mambo Alí Babá" instead of a state-commissioned carnival merengue—a significant change even from the National Parade that I saw in 2010.

Audio 4: “Cuida tu Celular” by The Kings of Mambo.

However, despite its current success and popularity, the delayed emergence of a "real" Dominican carnival music is continually shaped by a general apprehension of Haiti and blackness that is still prevalent in the Dominican Republic. Even in the twenty-first century as Afro-Dominican groups like the guloyas gain recognition within mainstream Dominican society and organizations like UNESCO, many cultural practices still understood as "Haitian" remain on the outskirts of acceptance. In February of 2010, the Ministry of Culture (under the auspices of Minister José Lantigua) unveiled a photo exhibition of many typically Dominican carnival comparsas from around the country. The exhibition included photos of Alí-Babá, the guloya, and even gagá—demonstrating a kind of official recognition of these comparsas as integral parts of Dominican carnival. However, although the caption accompanying the Alí-Babá photo duly credits the guloya musical influence in the rhythm of the snares and bass drums of the Alí-Banda (see also Tejeda Ortiz 2008), there was no reference to the sonic influences of gagá—even though the prominent use of fututo-like trompetas as the primary melodic ostinato instrument clearly indicates otherwise. This significant detail is still absent from most other scholarly considerations of the Alí-Banda sound as well.

In conclusion, the Dominican state’s dream for the National Parade has not yet been totally realized because the formation of a unified "Dominican" celebration, comprised of distinct regional traditions, has still proven somewhat elusive. However, perhaps the most interesting carnival phenomenon to emerge in recent years—and the strongest indication of a more unified national carnival—is the Reality Show "Vive el Carnaval de Noche y de Día" (a testament to the enduring significance of Días’s "Baila en la Calle [de Noche y de Día]") that premiered in 2011 and is co-produced by Media World Dominicana and the Ministry of Culture. Beginning in late January, a staggering 800 comparsas from around the country compete on television—first by region, then on a national level in Santo Domingo—with the finalists winning a chance to perform in the National Parade and for a grand prize of around US$14,000 (Ministerio de Cultura 2012). For the first time, Dominicans throughout the country can watch carnival dance/music traditions—Monday through Friday—from around the country without even leaving their homes. In the 1980s and 1990s, Alí-Babá became an integral part of the local carnival identity in the capital’s municipalities in part because, unlike gagá or the guloyas, it is not linked to a specific community, tradition, or context outside of carnival. Since its inception, even without the direct support of the state or the media, the popularity of the “Alí-Banda” had already spread to regional carnivals at the edges of Santo Domingo and regions beyond and to other comparsas not competing in the Alí-Babá category that, in the past, traditionally performed without live music. As a partial commercial enterprise, the reality show has set the stage for the Alí-Babá to take the whole country by storm.

In this paper, I have shown that the success and power of Alí-Babá at Dominican National Carnival since the 1980s stem from a flexibility and ability to incorporate multiple Dominican genres and performance practices. Today, various other typical carnival characters from both the capital and interior are now often accompanied by Alí-Bandas (like roba-la-gallina, Califé, and the diablos cojuelos) in place of their tradition of performing without live music (Video 3).

Video 3: Comparsas from the interior (2010).

As more groups desire to incorporate live music into their comparsas, the low cost, widespread availability, and portability of the typical Alí-Banda instruments make them the most logical choice (especially considering the distance most regional comparsas must travel to participate in the National Carnival Parade). The success of the Alí-Babá among Dominican carnival practitioners is twofold. One reason, rather ironically, may be due to its ability to bridge the desires of the Dominican state and the Dominican people. Another reason is that it does not necessarily limit the potential creativity or spontaneous nature of regional carnival practices—thus making Alí-Babá and the "Alí-Banda" as "real" and as "Dominican" as carnival may ever be.

References

Austerlitz, Paul. 1997. Merengue: Dominican Music and Dominican Identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Damirón, Casandra. 2009. "Alí Babá y sus 11 comparsas." Diario Libre, 23 February. (accessed 26 March 2011).

Desfile Nacional de Carnaval: Programa. 2009. Santo Domingo: Secretaría de Estado de Cultura.

———. 2010. Santo Domingo: Ministerio de Cultura.

———. 2011. Santo Domingo: Ministerio de Cultura.

———. 2012. Santo Domingo: Ministerio de Cultura.

Hernández, Mariano. 2010a. "Gagá." Photograph. Carnaval Dominicano Exhibition, Santo Domingo.

———. 2010b. "Teatro Cocolo Danzante Los Guloyas." Photograph. Carnaval Dominicano Exhibition, Santo Domingo.

Inoa, Orlando. 2005. Los Cocolos en la Sociedad Dominicana. Santo Domingo: Helvetas.

Lizardo, Fradique. 1974. Danzas y Bailes Folklóricos Dominicanos, vol. 1. Santo Domingo: Editora Taller.

———. 1979. Cultura Africana en Santo Domingo. Santo Domingo: Editora Taller.

Ministerio de Cultura. 2011. "Cultura Anuncia Amplio Programa Durante el Mes de Carnaval." (accessed 20 Feb 2011).

———. 2012. "Inicia Reality Show 'Vive el Carnaval de Noche y de Día.'" (accessed 25 Jan 2012).

Mota Acosta, Julio César. 1977. Los Cocolos en Santo Domingo. Santo Domingo: Editorial "La Gaviota."

Morrison, Mateo. 2009. Política Cultural, Legislación, y Derechos Culturales en República Dominicana. Santo Domingo: Editora Búho.

Peralta, Miguel. 2010. "Alí Babá." Photograph. Carnaval Dominicano Exhibition, Santo Domingo.

Primer Congreso Nacional de Carnaval: Acuerdos Finales. 2006. Santo Domingo: Editora Nacional.

Rosenberg, June C. 1979. El Gagá: Religión y Sociedad de un Culto Dominicano; Un Estudio Comparativo. Santo Domingo: Editora de la Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo.

Tejeda Ortiz, Dagoberto. 2008. El Carnaval Dominicano: Antecedentes, Tendencias, y Perspectivas. Santo Domingo: Amigo del Hogar.

———. 2010. Economía y Carnaval en La Vega, República Dominicana. Santo Domingo: Editora Nacional.

Discography

Various. 2006. Carnaval Dominicano: Un Siglo de Música Dominicana. vol. 12. Secretería de Estado de Turismo de la República Dominicana. [No catalog number.]

Various. 2006 [2001]. Música de Carnaval. Original production 2001. Fundación Cultural Bayahonda. [No catalog number.] Re-Released 2006.

External Links

Diaz, Luis y Sonia Silvestre. 16 April 2011. Luis Diaz y Sonia Silvestre baila en la calle.m4v -->. Video posted to YouTube. (accessed 10 March 2012).

Flow Magazine, vol. 153. 2008. (accessed 10 March 2012).

Union carnavalesca.17 February 2012. JUEVES 16 DE FEBRERO 2012 reality vive el carnaval noche y dia.mp4 -->. Video posted to YouTube. (accessed 10 March 2012).

Vive el Carnaval de Noche y Dia. 2012. [Facebook page] (accessed 10 March 2012).