Another Typical Day at the Office: Working Life in the Portuguese Independent Music Scene

The analysis of music scenes in urban contexts has traditionally focused on music production practices, without giving relevance to how these very practices are grounded in the organizational and economic dynamics that characterize the cultural and creative economy. However, several authors have advocated for a broader understanding of contemporary forms of music production, towards the consideration of the professional and economic dimension of musical activity (Tarassi 2018). These authors acknowledged the urgency to look at music production as a professional activity, which requires a set of skills that go beyond musical ability and which encompasses management and negotiation skills, like any other professional career. It is therefore important to understand how music and work in music are taken at the intersection between art, creativity, and economy; how trajectories in music are constructed; what strategies are mobilized by musicians, and the different actors that compose the musical field to ensure the sustainability and economic viability of their trajectories; what are their working conditions and consequent impacts on their daily lives, in a contemporary context.

Several authors have focused on the construction and structuring of musical careers, paying special attention to the living conditions of musicians and the strategies they mobilize to achieve economic sustainability. The work of Oliver (2010) shows the importance of new technological tools in the search for self-sufficiency by musicians, particularly in the context of the creative and management processes in which they are involved. In regard to the Austrian context, Rosa Reitsamer and Rainer Prokop (Reitsamer 2011; Reitsamer and Prokop 2018) analyzed the processes of construction and structuring of the careers of techno and drum’n’bass DJs, as well as hip-hop musicians, showing how these underground artists manage their careers in a flexible, self-responsible and DIY approach. In the Francophone context, Marc Perrenoud and Pierre Bataille (2017) have developed work on the French and Swiss music scenes, identifying different ways of being a musician, depending on the artists’ living conditions and their different sources of income.

This article focuses on the Portuguese context. It seeks to reveal the activities developed by the different actors that compose the world (Becker 1982) of independent music and the strategies they mobilize to guarantee the sustainability and economic viability of their careers, which are closely linked to their perceptions of music and work in music. Recognizing the importance of the production of sociological knowledge based on the representations of social actors and their processes of signification, my approach essentially relies on qualitative methods, based on a set of seventy-one semi-structured interviews with different actors in the independent music world (musicians, promoters, label owners, producers, agents, music venues programmers/curators, critics/journalists, and broadcasters) from two metropolitan areas: Lisbon and Porto. These interviews were conducted between May 2016 and March 2018, and the sample was constructed from the theoretical sampling approach and the snowball technique. The sample was constructed on the basis of its relevance to the theoretical approach and categories adopted in the research. I started from a set of privileged informants and key players in the Portuguese independent music scene, previously identified, which facilitated the entry into the field and allowed the identification of other members of the music scene to interview. While conducting interviews I adopted the life history approach (Bertaux 1997) to obtain as detailed a description as possible regarding the interviewees’ life trajectories, the construction of their musical taste and their connection to music, their forms of belonging to the music scene under study, and their performance strategies in it. The interviews were fully transcribed, using f4transkript, and submitted to a vertical and horizontal content analysis (Bardin 2011) using NVivo.

Creative work and music as a profession

The basic premise on which the understanding of music as a profession is based is the refusal of dichotomous visions that oppose music to the business world and to commercial logics, thereby detaching the exercise of creative activity from any presumption of substantial rationality. Binary representations that oppose the idealism of the artist to the materiality of work, the figure of the subversive and bohemian creative to that of the bourgeois worker concerned with social norms, or even the “art for art’s sake” to the world of business and commerce, are no longer relevant. Rather than considering them as distant, we assume that art, creativity, and economy intersect in a complex space of tensions, negotiations, and struggles (Negus 1995; Menger 2005; Hesmondhalgh 2019).

This research starts precisely from the understanding of artistic and creative activities, and more specifically from the set of activities developed around music as a profession, as work, as employment. Therefore, I rely on authors such as Angela McRobbie (2016), for whom artists and creatives anticipate the future of work and the forms in which careers are consolidated in a neoliberal context and under the aegis of the “economy of talent.” In this regard, Menger stated that “not only are creative artistic activities not or are no longer the opposite side of work, but they are increasingly taken to be the most advanced expression of new modes of production and new employment relationships engendered by recent mutations in capitalism” (Menger 2005:44). For authors following this rationale, it is clear that “artistic worlds have learned to live with the pressures of economic efficiency and the criteria of profit, not to exonerate themselves from them, but to accommodate them to their guiding principles” (Menger 2005:61).

The work carried out over the last few years clearly identifies the main characteristics of the forms of work organization in artistic, cultural and creative professions: There are frequent situations of self-employment, but also different forms of underemployment (part-time non-voluntary work, intermittent work, fewer working hours). It is also common to be involved in several projects simultaneously and to work for different employers. Traditional linear careers give way to a succession of projects and experiences in a structuring logic based on flexibility and discontinuity; the prospects for career development tend to be quite uncertain and risky, with a strong inequality of income but also of reputation and recognition (Menger 1983; Menger 1999; McRobbie 2004; Menger 2005; Menger 2014; McRobbie 2016; Perrenoud and Bois 2017; Sinigaglia 2017; Everts, Hitters, and Berkers 2021). Workers are expected to be increasingly multi-skilled and to adapt easily and quickly to new projects and new tasks. In this context, investment in the acquisition and consolidation of social capital (Bourdieu 1993; Bourdieu 1996) is crucial to ensure the viability of these trajectories, which makes networking and gatekeeping processes preponderant in accessing work opportunities and therefore in building and maintaining artistic and creative careers.

Given the specificities of how artistic and creative work is organized, several strategies are mobilized for the construction and maintenance of these careers. One of the main strategies involves an exercise of splitting, reflected in the multiplication of professional occupations, through the accumulation of different jobs in the same period, in a logic of multi-activity. These professionals often divide their working time with tasks related to the artistic and creative sphere, but which go beyond the act of creation or preparation of the artistic/creative product itself (Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2011; Hracs 2015; Haynes and Marshall 2018).

Moreover, without the predictability and monotony of routine work, these types of work are characterized by great uncertainty. But if uncertainty is seen as one of the conditions of originality, innovation, and personal satisfaction and fulfilment in relation to the creative act, it also has a negative dimension, often creating states of anxiety. In addition, several studies have shown that the autonomy, freedom, and flexibility associated with artistic and creative work are counterbalanced with harsh working conditions and precarious daily experiences: long working hours, sometimes unpaid or in exchange for a reduced salary; difficulty in balancing artistic and creative careers with family life, particularly felt by women; nervousness, anxiety, frustration, and a loss of self-esteem generated by the instability of these careers; a continuum between work and leisure stemming from the need for socialization and networking; and a tendency towards individualization, the privatization of disappointment, and self-blame for failures (McRobbie 2002; Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2010; Hesmondhalgh and Baker 2011; Campbell 2013; McRobbie 2016; Tarassi 2018).

Considering these characteristics, some authors argue that, along with the transformation of society towards an intensification of individualism, the artistic, cultural, and creative labor market is also becoming increasingly individualized, following a neoliberal model, and governed by the values of entrepreneurship. Expressions such as “cultural entrepreneurs” (Scott 2012) or “subcultural entrepreneurs” (Haenfler 2018) have been used to refer to musicians and other social actors in music scenes who manage their careers without being dependent on intermediaries such as record labels, managers or agents. It is recognized that these actors present characteristics associated with an entrepreneurial attitude (flexibility, resilience, creativity in problem-solving, capacity to deal with risk and uncertainty) and that, in their daily lives, they engage in activities considered as entrepreneurial — networking, ensuring the funding of projects, organizing concerts and tours, promoting their work and events to the public and different gatekeepers (e.g., journalists, critics, radio broadcasters, and programmers). In fact, as Haynes and Marshall argue, this is rather expected, especially in the field of popular music where musicians are usually self-employed (Haynes and Marshall 2018). But these types of commercial and promotional activities are and have always been part of a musician’s work. Therefore, they are not something that solely results from the transformations that occurred in the music industry (although they may be intensified by them), but rather are a continuation of already existing work patterns. Referring to the work of William Weber on the status of musicians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and of Tia DeNora on Beethoven (and we add, of Norbert Elias on Mozart), Haynes and Marshal argue that musicians are and always have been both cultural and economic figures (Elias 1993; DeNora 1995; Weber 2004; Haynes and Marshall 2018).

The DIY approach in the analysis of music careers

Though the work activities of musicians have mainly been conceptualized through an entrepreneurial perspective, another analytical approach is possible by focusing on the concept of DIY. The Portuguese independent music scene in particular can be studied through the DIY concept, allowing an understanding of musicians and other actors of the music field as managers of their careers and protagonists of a logic of development of multiple competencies. They assume simultaneously several and complementary roles —as musicians, producers, editors, designers, promoters, and agents — generating intersections between diverse artistic and creative subsectors, and also challenging the boundaries between the professional and the amateur (Hennion et al. 2000). This emphasis is based on social theory’s revisiting one of the core values of the punk subculture — the DIY ethos (McKay 1998; Dale, 2008; Dale 2010; Moran 2010; Olivier 2010; Hein 2012; Guerra 2013; Guerra 2018; Bennett and Guerra 2019). If at the beginning of the twentieth century, the term DIY referred to the practices of creating, repairing, and/or modifying something without recourse to an experienced craftsman/professional, its meaning gradually evolved over the following decades to encompass a wide range of cultural and creative practices (Bennett and Guerra 2019).

Within a music production mode symbolically and ideologically distinct from the commercial circuits of the music industry, during the 1980s and 1990s the DIY ethos remained strongly linked to the punk aesthetic but extended to other musical genres and other spheres of alternative cultural production (Bennett 2018). Thus, Bennett and Guerra argue that “while by no means eschewing anti-hegemonic concerns, this transformation of DIY into what might reasonably be termed a global ‘alternative culture’ has also seen it evolve to a level of professionalism that is aimed towards ensuring aesthetic and, where possible, economic sustainability” (Bennett and Guerra 2019:7). The concept of a DIY career implies understanding it as a form of professional trajectory, which stems from the need to manage the “pathological effects” of post-industrialization and, consequently, the risk and uncertainty that characterize contemporary societies. In a context like the one we live in — the “risk society” (Beck 1992) — not only are biographical trajectories more uncertain and unpredictable, but processes become increasingly individualized, and social actors are driven to create their own trajectories. It is in this sense that we can understand DIY careers as a pattern of promoting employability based on knowledge acquired through practice, contact with peers and, often, participation in youth subcultures (Oliveira 2020).

For these reasons, DIY has become representative of a wider ethos of lifestyle politics, with repercussions on people’s personal projects and professional choices, on a global scale (Bennett and Guerra 2019). And in this scenario of redefining the meaning of DIY, we are now witnessing the growth of levels of professionalization that characterize much of the contemporary DIY cultural production sphere (Bennett 2018; Tarassi 2018).

Strategies for career development in the independent music scene

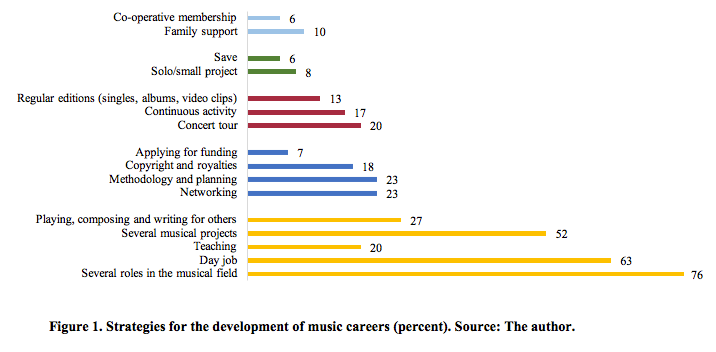

The changes that have taken place in recent decades in the global record industry and more broadly in the world of music have been well documented in the Portuguese context by the work of Paula Abreu and Paula Guerra (Abreu 2010; Guerra 2010). They have shown how these changes have brought new opportunities and challenges to musicians and the wide range of professionals that compose the music field. Specifically, these changes have implications for the ways these social actors carry out their activities and, consequently, on how they ensure the sustainability of their careers. In this sense, my research has confirmed that a music career involves the combination of several strategies and, therefore, of several sources of income (Oliveira 2019; Oliveira 2020). Figure 1 provides an overview of this diversity.

A logic of multiplication

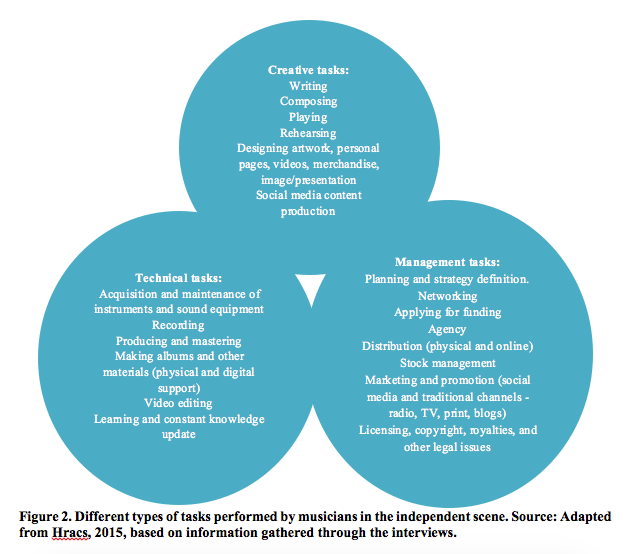

In line with the results of other research on the construction of music careers, the main set of strategies mentioned by my interviewees follows a logic of multiplication, taking different forms (yellow bars in Figure 1) (Guerra 2010; Reitsamer 2011; Guerra 2015; Gavanas and Reitsamer 2016; Perrenoud, Marc and Bataille 2017; Reitsamer and Prokop 2018; Reitsamer 2011). First, through the performance of different roles in music, both in terms of personal projects and in terms of working with other actors in the music field — a strategy mentioned by seventy-six percent of our interviewees. This is the materialization of the DIY ethos, ensuring control over several stages of the process of making and disseminating music, often as a combination of the will to do so and the need to do so due to the scarcity of available resources (Strachan 2003; Strachan 2007; Dale 2008; Dale 2010; Drijver and Hitters 2017). To the creative dimension of writing, composing, and playing, these actors add many other roles — those of producer, editor, promoter, agent, DJ, designer, and others. Having a career in music depends on much more than knowing how to sing or play an instrument (Figure 2). It is necessary to know the field and its logics, but also to ensure a range of more administrative and bureaucratic activities. We are here before what Perrenoud and Leresche designate as one of the four types of invisible work that are part of musical activity — the perimusical work (Perrenoud and Leresche 2016).[1] This includes all the non-musical tasks that are materially necessary for the musician’s activity. It includes all the work of organization and administration, ensuring tasks such as planning and budget management; applying for funding; promotion of the artist/band and projects in different communication channels and thinking both about the public and gatekeepers; booking concerts; event organization; and other tasks. The authors also include maintenance work, which has a logistical dimension, manifested for example in the transportation and installation of instruments and sound equipment during concerts.

In most cases, the skills required to perform these activities are acquired through practice and through contact with peers, both in person and online. The predominance of intermittent employment within the scope of musical work encourages the polyvalence of musicians. Technological evolutions, mainly at the level of record production, have contributed to the greater independence of musicians in relation to social actors such as producers and labels. In recent decades there has been a confluence of technological, economic, and socio-cultural factors that have facilitated musicians to take on tasks that they used to delegate, such as production and editing.

The multiplication of roles played on the music scene contributes to the acquisition of symbolic and cultural capital, reinforcing the position of these social actors in the subfield of independent music (Bourdieu 1993; Bourdieu 1996). By diversifying their area of activity, musicians conquer symbolic legitimacy within the networks in which they are involved. Thus, there is a strong investment in terms of relational capital, in the sense that playing different roles allows the creation and maintenance of more and more diversified relations.

A second form of multiplication, mentioned by sixty-three percent of interviewees, involves combining music with another profession, which may or may not be related to it or to the artistic and cultural environment. Within the framework of our research, of the fifty-three interviewees working as musicians, only eight were exclusively dedicated to music, while thirty-eight claimed to combine it with other activities, and the remaining seven reported being students. Activities developed in parallel with the activity of a musician included those of promotion, music publishing and music production, as well as teaching in areas such as design and architecture, and work in sound technology. These are activities relating to the artistic and cultural environment, which are recognized by interviewees as advantageous. In the case of the eighteen non-musicians interviewed, only two combined their activity in the musical field with another profession not related to the artistic area (one of the interviewees worked at a housing company and the other was the owner of a transport company). This suggests that for a musician, professional work in other activities around music is easier than pursuits unrelated to music.

For some of the interviewees, this combination with other activities was a strategy they turned to only during periods when music work was not enough to ensure their economic sustainability. However, in most cases, this activity constituted a permanent job, and not infrequently, the main job. In either situation, the flexibility of schedules is valued to facilitate rehearsals, concerts, and tours. However, there are different perspectives regarding this occupational division. For the majority (sixty-two percent of the interviewees who have another profession besides music), this situation stems from the need to seek a balance between financial pressures and the possibility of maintaining their creative passions. Indeed, these musicians face the conflicts and tensions inherent in the search for mental, temporal, and economic space to be creative while also meeting everyday needs, which can create different opportunities for engagement with creativity and a career in music (Threadgold 2018). On the contrary, the remaining interviewees, and especially those who denote a more emotional attitude towards music, clearly state that music is for them a “territory of freedom” and, as such, they do not want to economically depend on it.

In my case, it’s impossible to live only from music. I live from the work I do outside music, which is architecture. It was completely impossible to live only from music. There are a lot of expenses and the money is not enough. With two jobs, it’s difficult. So, it was completely impossible. And it wasn’t something I didn’t want. If I could live only from music, I would live only from music, but I can’t.

Tiago, 31 years old, master’s degree, musician, and architect, Cascais.

I have been an architect since I finished my degree, and I am self-employed as an architect. (...) In strategic terms, my option is to have music as a part-time... Music is a part-time job to which I dedicate a lot of time, time that I feel is fairly rewarded nowadays, but it is already structural for me this idea that I don’t want to depend on music. Music for me is a territory of total freedom. I’m not going to give that up, so, for me, music will always be this second professional home, although in fact, in terms of my emotional involvement with it, it is often the first.

Baltazar, 40 years old, bachelor’s degree, musician, and architect, Barcelos.

Being a teacher, organizing workshops, or providing classes on a more informal and occasional basis also seems to be a common activity, mentioned by fourteen interviewees (twenty percent). Within the set of roles that can be played, being a teacher is especially relevant, insofar as it consists of a division that does not imply a detachment from the area of music and may even contribute towards the acquisition of different kinds of capital that are essential for a good position in this particular subfield (Menger 1999; Menger 2006).

The involvement in several musical projects is a third way in which this logic of multiplication is translated, mentioned by fifty-two percent of our interviewees.[2] In fact, this strategy is seen in a very positive light. On the one hand, it allows the manifestation of different identities, styles/genres, and artistic languages, in addition to also enabling musicians to play different instruments. The plurality of musical projects is thus perceived as a factor of enrichment and evolution in professional terms. On the other hand, on a more rational and strategic level, considering the importance of live music, the multiplicity of musical projects makes it possible to play several times in the same concert venues, without repeating the project, thus broadening the sources of income. If the times and rhythms of each project are well balanced, it can allow a continuous activity.

Still in this first set of strategies that implies multiplication, for twenty-seven percent of our interviewees, one of the strategies is precisely to be a musician in different ways. In other words, to be a creator and author, but also what is commonly called a session musician, i.e., to play with other artists, whether occasionally or consistently. Also included here are musicians who write and compose for other artists, as well as those who compose soundtracks for cinema, theatre, dance shows, television, and advertising. This is a very important strategy, especially in the case of those who live only from music.

However, considering the ambiguity within which musical careers are built, these different forms of multiplication should perhaps be understood as a necessary and differentiating element of independent music production practices. They also have less positive dimensions, which have been taken into consideration by my interviewees (seventeen percent) — notably, difficulties of time management and of defining priorities between the different roles assumed in the music scene, between the creative dimension and the more administrative and managerial ones. These tensions emerge from the time, concentration, and energy spent on creating, and on generating the necessary income. The long days of work and the consequent fatigue (which is not productive in creative terms) that this implies were also mentioned. In this way, once the risks in terms of the quality of creative work are recognized, the different forms of multiplication portrayed here are seen by this set of interviewees as accentuating the precarious nature of musicians’ work, simultaneously calling professionalism — and the capacity for professionalization — into question:

It is not an aspect that I find particularly positive. It would be more interesting if it didn’t have to be like this, but nowadays bands make their posters, their communication, they manage their social networks. All these are skills that go far beyond the work as a musician. And this also takes time away from that work. And, if it is already done in relatively precarious conditions, in most cases, it only makes them more precarious. There is less time and less focus on the creative issue. But it is the model that works best now. It is almost an obligation. Musicians must multiply, and they must be able to answer a lot of questions and understand them.

Baltazar, 40 years old, bachelor’s degree, musician, and architect, Barcelos.

The music like any other profession

A second set of strategies exists. When interviewees consider music as any other profession, they express a rational perspective (dark blue bars in Figure 1).[3] Calling to mind the relational and collective dimension of music — understanding it as the result of the combined work of different actors — another essential strategy for building and maintaining a music career is networking (mentioned by twenty-three percent of interviewees), (Becker 1982; Crossley, McAndrew and Widdop 2014; Crossley 2015; Crossley and Bottero 2015; Guerra 2015; Mcandrew and Everett 2015). For musicians, it is often important to be associated with groups of artists, especially when these groups include people with complementary skills and roles such as production, editing, and management. These “artistic communities” draw on the various types of capital (symbolic, cultural, social, and economic) that their members possess, and at the same time, these actors see their position and reputation in the music world strengthened as a result of belonging to these groups.

At the same time, these interviewees recognize the importance of “knowing the right people” — essentially, those who act as gatekeepers, who can generate work opportunities, or can promote the musicians and their projects. This is what Perrenoud and Leresche identify as one of the forms of musicians’ invisible work — the work of socialization (Perrenoud and Leresche 2016).

Simultaneously, interviewees recognized the relevance of informal and face-to-face relationships established while attending nightlife venues for musical fruition and socializing. They know that it is essential to go to each other’s concerts, to go out at night and strengthen relationships with peers, especially when they have something new that needs to be promoted, be it an album, a single, a music video, or a new project they are involved in. Thus, the divisions between leisure and work, and between production and consumption become blurred, which is a characteristic feature of small-scale cultural production circuits. Insertion in networks and the acquisition of relational and social capital, capable of creating a system of trust and mutual aid, but also of reputation, is essential (Crossley 2008; Scott 2012; Crossley and Bottero 2015; Mcandrew and Everett 2015; Reitsamer and Prokop 2018; Tarassi 2018). These networks function as platforms for acquiring skills and knowledge essential to the different roles that a music career entails. At the same time, they can promote new job opportunities, as they tend to be used as the main channel for recruiting new talent and finding new jobs.

The city in which musicians and other actors in the music field were based was not explicitly stated by interviewees as an important factor in the construction and management of their careers. Rather, the informality that characterizes the relationships in the music world and the emphasis that is given to personal contact, in moments of leisure and socializing, mean that the city and the spaces for meeting and musical fruition of the independent music circuit assume extreme relevance for the construction of these careers. More specifically, the concentration of gatekeepers in Lisbon makes it a crucial locale for musicians, meaning musicians living in Porto or in other cities of the country may find networking more difficult.

Another strategy mentioned by twenty-three percent of interviewees is the need to plan one’s career by defining objectives, a schedule, and a work methodology. Here a rational and methodical dimension of music takes on importance, as opposed to the romantic vision of musicians as bohemians, and of music as the result of their inspiration and genius. For the interviewees who report this strategy, music is a work that implies dedication, commitment, and many hours of work around all the details of the music (lyrics, composition, arrangements...). It implies a great deal of self-discipline, which involves setting schedules and deadlines. It also implies thinking of the career as a process with distinct phases, identifying priorities and defining a strategy to achieve them. Though they acknowledge all the creativity and pleasure associated with the moment of creation, they differentiate it from the moment of execution, i.e., production and promotion, which implies planning and well-defined strategies to transform the musical creation into economic returns. This notion calls to mind the argument of Keith Negus, who questioned some of the assumptions about the rational nature of the market on the one hand, and the “mystical” nature of creative inspiration on the other (Negus 1995). In his view, a binary approach based on the opposition between creativity and commerce is not the most fruitful one. According to the author, the production of popular music does not really involve a conflict between commerce and creativity as a struggle over what is creative and what should be commercial. This is precisely the logic that we find in the discourses of this group of interviewees. The creative dimension, imminently pleasurable and where a more emotional connection to music is evident, manifests itself above all at the moment of conception and creation. In the following phases, a more rational dimension is added, relating to the strategies used to make music a financially viable option. The combination of these two components, and not their opposition, is essential to enable the sustainability of a music career.

Music is not born from acts of genius. It is born from acts of work, dedication, and discipline. It is going through trial and error to see what works. (...) Discipline, methodology, and effort are the most important things to be able to make a serious and profitable business. This is a very important strategy to make a living from music. You must see it as any other job.

Gabriel, 26 years old, bachelor’s degree, musician, and designer, Lisbon.

In this set of strategies, we also included in this set of strategies the use of copyright and royalties, which was identified as a relevant strategy and source of income for eighteen percent of the interviewees. In fact, illustrating the strategic management dimension of careers, some of the musicians we interviewed consider the income obtained through the copyright and royalties as a kind of savings that they accumulate and resort to when concerts are less frequent.

Also, in this set of strategies, it is pertinent to underline the applications for support and funding, be it occasional, for a tour, the release of an album or the organization of events. The use of these types of funding is a strategy mentioned by seven percent of the interviewees, allowing the development of their artistic work in a context of greater stability. However, some difficulties remain — namely, those related to the complexity of some application for funding processes. Similarly to what Campbell emphasized in the Canadian case, there is the problem of a lack of preparation for this kind of administrative work, which is increasingly a reality in the daily lives of these musicians (Campbell 2013). An idea also present in Hugo’s words:

We were making an application. Most musicians can’t make an application like this. Even the training that musicians have in schools and universities... Musicians are not prepared for these kinds of realities that, sooner or later, everyone will have to face. We were thinking that in the curricula of the courses, musicians should be more prepared to adapt to this type of realities. Really, a musician’s life is not just about playing. There is a lot of administrative work that must be done.

Hugo, 41 years old, PhD student, musician, sound technician, teacher, Porto.

A logic of continuity

Within a third set of strategies, grouped under a shared logic of continuity (red bars in Figure 1), there are live performances and concert circuits. With the worldwide decline in record sales, live music has become the main source of income for musicians (Wilkström 2009). Twenty percent of the interviewees mentioned that playing as often as possible is an essential strategy. This implies availability to play in different venues and stages and for different audiences. Sometimes it also implies playing in venues with few conditions. At the same time, it presupposes the strengthening of ties with promoters and programmers of concert venues who, due to the centrality of live music, are increasingly key players.[4] In fact, this can be seen as one of the main changes in the power relations in the music scene.

It’s trying to be always active, always doing something, always promoting, trying to give many concerts. It’s trying to organise the whole scheme in the best way possible, so that we can direct the funding we have to what is worthwhile. Music, nowadays, gives us money through concerts, royalties and almost nothing else. Music is no longer bought, what you get out of it is a minimal profit. The goal is to play all the time, to do new things so that we can play more often.

Tânia, 31 years old, higher education, musician, dance teacher and actress, Porto.

Equally relevant is maintaining continuous activity, never stopping. In other words, one of the strategies (mentioned by seventeen percent of interviewees) is to ensure the continuity of the creative cycle by always being involved, whether through composing, recording, producing, editing, or playing. In this way and considering the interconnection between all these strategies, musicians manage to increase the possibility of performing concerts, collecting royalties, and attracting the attention of both the public and the media, boosting their visibility. At the same time, this logic of continuity requires a constant investment, a capacity for adaptation and reinvention on the part of musicians and other actors who have made music their professional career.

A logic of reduction

A fourth set of strategies mentioned by our interviewees highlights a logic of reduction (green bars in Figure 1). This is the case of the reduction of the size of musical projects. According to interviewees, it is common for a band with several elements to have more difficulties in booking concerts outside the city where it is based. In logistical terms, the higher costs of transportation and accommodation render the band more expensive and therefore less attractive. At the same time, the larger the size of the band, the greater the division of income. For these reasons, reducing the size of musical projects or even opting for solo projects were strategies mentioned by eight percent of our interviewees. In a complementary way, six percent mentioned the need to save, reduce costs associated with musical activity, and adapting to available resources. It is often precisely for this reason that the DIY ethos manifests itself. But the logic of saving extends to the other spheres of life of our interviewees, who say that they “have a life without many luxuries.” They have modest objectives — paying the bills through their work and ensuring the continuity of their musical projects — and adapt their lifestyle to what they can effectively afford. These discourses comment on processes of adjustment and reduction of expectations that allow them to justify the continuation of their careers even when financial return is low (Campbell 2013; Sinigaglia 2017).

At the time of the first album, I was with a very big band, I was playing with five people. So, I was asking for two thousand euros per concert. To get into the independent scene, two thousand is already a lot. So, I had to go back to being just guitar and voice. I play with the computer. And I’m not going to put a structure on it again any time soon, because it’s a huge risk.

Dalila, 27 years old, university attendance, musician and photographer, Porto.

Finally, we consider it relevant to mention one other strategy, mentioned by ten percent of the interviewees (light blue bars in Figure 1): reliance on family support (parents and/or partners). These support networks were identified as one of the ways of dealing with the uncertainty, instability, and precariousness that characterize these DIY careers. The ability of social actors from privileged backgrounds to use family economic resources is fundamental in insulating them from much of the precariousness and uncertainty associated with their career (Friedman, O’Brien, and Laurison 2016). It seems that two essential aspects are involved here. The first is the idea defended by Threadgold that if the precarious nature of these trajectories is undeniable, it is important to remember that it is a precariousness chosen reflexively and not imposed (Threadgold 2018). The second aspect refers to one of the factors facilitating this choice: the family socio-economic background, i.e., the class origin of these social actors as an element encouraging their involvement in DIY careers. Similarly to previous studies portraying the alternative rock subfield and the punk scene in Portugal, our data shows that when compared to the general Portuguese population, the majority of our interviewees already have an advantage when it comes to economic, social and cultural capital (Guerra 2010; Guerra 2013; Abreu et al. 2017).[5]

Conclusion

The main objective of this article was to understand the work activities developed by musicians and other actors in the Portuguese independent music scene, as well as the strategies applied to ensure the sustainability and viability of their careers. This research concludes that a music career implies combining several strategies and, therefore, several sources of income. The main set of strategies mentioned by our interviewees follows a logic of multiplication, which can take different forms. First, we found that the performance of different roles in the music field is a characteristic feature of independent music production. Based on a DIY ethos and praxis, this multiplicity of roles, in addition to allowing for less dependence on others, contributes to the acquisition of symbolic and cultural capital, reinforcing the position of these social actors in the field of music production. This implies that these actors engage in many activities alongside their creative work. They engage in administrative, promotional, and management activities, revealing that the dichotomous visions opposing art and commerce are not adequate for an analysis of their trajectories. The combination of music with another profession, such as giving lessons/workshops, being involved in several musical projects simultaneously, and playing, composing, and writing for others are also common strategies.

Closely associated with an eminently rational conception of music and musical activity, which understands music as any other profession, one of the crucial strategies involves promoting networks and networking, as well as planning one’s career, defining objectives, setting a schedule, and establishing work methodology. This also includes the use of copyright and royalties, as well as applying for support and funding.

A third set of strategies immediately highlights the centrality of live music in the processes of building and consolidating musical careers. Today, concerts and tours have not only become the main source of income for musicians, but also reveal themselves to be an essential activity for the creation and consolidation of networks and for building a reputation in the musical field. For this reason, one of the main strategies mobilized by these interviewees is to perform as many live performances as possible. To make this possible, they try to be constantly active, editing new music regularly and getting involved in several musical projects simultaneously. At the same time, a reduction in the size of musical projects, manifested in smaller bands and the creation of solo projects, is also a way of not only reducing the costs associated with musical activity and adapting it to the resources available, but also a strategy to boost invitations for live performances.

Inevitably, the centrality that live music has gained has changed the power relations in the music field. If in the past record labels played a key role, today musicians are less dependent on these structures, partly thanks to digital technologies and the Internet. On the other hand, today the promoters, agents, and programmers of concert venues are the central figures of the musical field, insofar as the possibilities of live performance largely depend on them.

In summary, based on these results, I formulate two main theoretical conclusions. First, this analysis shows the importance of research that considers the diversity of workers’ experiences in the creative industries, and specifically in music. More specifically, it reveals the relevance of analyses that combine a look at the activities developed on a daily basis by these actors and consequently, the strategies they mobilize with their perceptions regarding music and musical activities. At this level, our research contributes to the growing theoretical corpus that rejects binary views that oppose art and economics in the analysis of work in music. Second, by offering a deep focus on the working lives of musicians and other actors in the music world nowadays, our analysis contributes to the consolidation of live music as an important area of study. This is especially important in the current pandemic context, which poses new challenges to the functioning and sustainability of this sphere of the music field, especially in a country like Portugal, where the importance of the live music ecosystem is beginning to be brought into discussion.

Acknowledgements/Funding

This work was developed as part of the author’s doctoral thesis, Do It Together Again: redes, fluxos e espaços na construção de carreiras na cena independente portuguesa [Do It Together Again: networks, flows and spaces in the construction of careers in the Portuguese independent scene], supported by FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology, within the scope of the doctoral scholarship under reference SFRH/BD/101849/2014.

References

Abreu, Paula. 2010. A música entre a arte, a indústria e o mercado: um estudo sobre a indústria fonográfica em Portuga [Music between art, industry and market: a study on the phonographic industry in Portugal]. Coimbra: Faculdade de Economia da Universidade de Coimbra.

Abreu, Paula, Augusto Santos Silva, Paula Guerra, Ana Oliveira, and Tânia Moreira. 2017. “The social place of the Portuguese punk scene: an itinerary of the social profiles of its protagonists.” Volume! 14(1):103–126.

Bardin, Laurence. 2011. Análise de Conteúdo [Content Analysis]. Lisboa: Ediçoes 70.

Beck, Ulrich. 1992. The Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

Becker, Howard. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley and Los Angels: University of California Press.

Bennett, Andy. 2018. “Conceptualising the relationship between youth, music and DIY careers: a critical overview.” Cultural Sociology 12(2):140–155.

Bennett, Andy, and Paula Guerra, eds. 2019. DIY Cultures and Underground Music Scenes. London and New York: Routledge.

Bertaux, Daniel. 1997. Les récits de vie. Paris: Nathan University.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

------. 1996. As Regras da Arte [The Rules of Art]. Lisboa: Editorial Presença.

Campbell, Miranda. 2013. Out of the Basement. Youth Cultural Production in Practice and in Police. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Crossley, Nick. 2008. “Pretty Connected: the social network of the early UK punk movement.” Culture & Society 25(6):89–116.

------. 2015. Networks of Sound, Style and Subversion: the Punk and Post-Punk Worlds of Manchester, London, Liverpool and Sheffield, 1975-80. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Crossley, Nick, Siobhan McAndrew, and Paul Widdop, eds. 2014. Social Networks and Music Worlds. London: Routledge.

Crossley, Nick, and Wendy Bottero. 2015. “Social Spaces of Music: Introduction.” Cultural Sociology 9(1):3–19.

Dale, Pete. 2008. “It was Easy, it was Cheap, so What?: Reconsidering the DIY Principle of Punk and Indie Music.” Popular Music History 3(2):171–193.

------. 2010. Anyone Can Do It: Traditions of Punk and the Politics of Empowerment. Newcastle University.

DeNora, Tia. 1995. Beethoven and the Construction of Genius: Musical Politics in Vienna 1792-1803. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Drijver, Robin den, and Erik Hitters. 2017. “The Business of DIY. Characteristics, Motives and Ideologies of Micro-Independent Record Labels.” Cadernos de Arte e Antropologia 6(1):17–35.

Elias, Norbert. 1993. Mozart. Sociologia de um génio [Mozart. Sociology of a genius]. Lisboa: Asa.

Everts, Rick, Erik Hitters, and Pauwke Berkers. 2021. “The Working Life of Musicians: Mapping the Work Activities and Values of Early-Career Pop Musicians in the Dutch Music Industry.” Creative Industries Journal 0(0):1–20.

Friedman, Sam, Dave O’Brien, and Daniel Laurison. 2016. “‘Like Skydiving without a Parachute:’ How Class Origin Shapes Occupational Trajectories in British Acting.” Sociology:1–19.

Gavanas, Anna, and Rosa Reitsamer. 2016. Neoliberal Working Conditions, SelfPromotion and DJ Trajectories: A Gendered Minefield. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität.

Guerra, Paula. 2010. A Instável Leveza do Rock: génese, dinâmica e consolidação do rock alternativo em Portugal [The Unstable Lightness of Rock: genesis, dynamics and consolidation of alternative rock in Portugal]. PhD thesis. Porto: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto.

------. 2013. A Instável Leveza do Rock. Génese, dinâmica e consolidação do rock alternativo em Portugal [The Unstable Lightness of Rock: genesis, dynamics and consolidation of alternative rock in Portugal. Porto: Edições Afrontamento.

------. 2015. “Keep it Rocking: The Social Space of Portuguese Alternative Rock (1980-2010).” Journal of Sociology 17:1–16.

------. 2018. “Raw Power: Punk, DIY and Underground Cultures as Spaces of Resistance in Contemporary Portugal.” Cultural Sociology 12(2):241–259.

Haenfler, Ross. 2018. “The Entrepreneurial (Straight) Edge: How participation in DIY Music Cultures Translates to Work and Careers.” Cultural Sociology 12(2):174–192.

Haynes, Jo, and Lee Marshall. 2018. “Reluctant Entrepreneurs: Musicians and Entrepreneurship in the ‘New’ Music Industry.” British Journal of Sociology 69(2):459–482.

Hein, Fabien. 2012. “Le DIY comme dynamique contre-culturelle? L’exemple de la scéne punk rock.” Volume! 9(1):105–126.

Hennion, Antoine, Sophie Maisonneuve, and Emilie Gomart. 2000. Figures de l’Amateur: formes, objets, pratiques de l’aniour de la musique aujourd’hui. Paris: La Documentation Française.

Hesmondhalgh, David. 2019. The Cultural Industries. London and Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hesmondhalgh, David, and Sarah Baker. 2010. “‘A Very Complicated Version of Freedom:’ Conditions and Experiences of Creative Labour in Three Cultural Industries.” Poetics 38(1):4–20.

------. 2011. Creative Labour. Media Work in Three Cultural Industries. London and New York: Routledge.

Hracs, Brian. 2015. “Cultural Intermediaries in the Digital Age: The Case of Independent Musicians and Managers in Toronto.” Regional Studies 49(3):461–475.

Mcandrew, Siobhan, and Martin Everett. 2015. “Music as Collective Invention: A Social Network Analysis of Composers.” Cultural Sociology 9(1):1–25.

McKay, George. 1998. DiY Culture: Party and Protest in Nineties Britain. London: Verso Books.

McRobbie, Angela. 2002. “Clubs To Companies: Notes on the Decline of Political Culture in Speeded Up Creative Worlds.” Cultural Studies 16(4):516–531.

------. 2004. “Making a Living in London’s Small-Scale Creative Sector.” In Culture Industries and the Production of Culture, edited by Dominic Power and Allen J. Scott, 130–144. New York: Routledge.

------. 2016. Be Creative: Making a Living in the New Culture Industries. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Menger, Pierre-Michel. 1983. Le Paradoxe du musicien : le compositeur, le mélomane et l’État dans la société contemporaine. Paris: Flammarion.

------. 1999. “Artistic Labor Markets and Careers.” Annual Review of Sociology 25(1):541–574.

------. 2005. Retrato do artista enquanto trabalhador: metamorfoses do capitalismo [Portrait of the artist as worker: metamorphoses of capitalism]. Lisboa: Roma Editora.

------. 2006. “Artistic Labor Markets: Contingent Work, Excess Supply and Occupational Risk Management.” In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, edited by Victor A. Ginsburg and David Throsby, 765–811. Amsterdam: North Holland.

------. 2014. The Economics of Creativity: Art and Achievement Under Uncertainty. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: Harvard University Press.

Moran, Ian. 2010. “Punk: The Do-It-Yourself Subculture.” Social Sciences Journal 10(1):58–65.

Negus, Keith. 1995. “Where the Mystical Meets the Market: Creativity and Commerce in the Production of Popular Music.” The Sociological Review 43(2):316–341.

Oliveira, Ana. 2019. “Do ethos à praxis. Carreiras DIY na cena musical independente em Portugal” [From ethos to praxis. DIY careers in the independent music scene in Portugal], in De Vidas Artes, edited by Paula Guerra and Lígia Dabul, 421–442. Porto: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto.

------. 2020. Do It Together Again: redes, fluxos e espaços na construção de carreiras na cena independente portuguesa [Do It Together Again: networks, flows and spaces in the construction of careers in the Portuguese independent scene.]. PhD thesis. Lisboa: Iscte - Instituto Universitário de Lisboa.

Oliver, Paul. 2010. “The DIY Artist: Issues of Sustainability within Local Music Scenes.” Management Decision 48(9):1422–1432.

Perrenoud, Marc, and Pierre Bataille. 2017. “Artist, Craftsman, Teacher: 'being a musician' in France and Switzerland.” Popular Music and Society 40(5):592–604.

Perrenoud, Marc, and Frédérique Leresche. 2016. “Les paradoxes du travail musical. Travail visible ei invisible chez les musiciens ordinaires en Suisse et en France.” Les Mondes Du Travail:85–96.

Perrenoud, Marc, and Géraldine Bois. 2017. “Ordinary Artists: From Paradox to Paradigm? Variations on a Concept and its Outcomes.” Symbolic Goods: A Social Science Journal on Arts, Culture and Ideas 1:2–36.

Reitsamer, Rosa. 2011. “The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum “n” Bass DJs in Vienna.” Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 3(1):28–43.

Reitsamer, Rosa, and Rainer Prokop. 2018. “Keepin’ it Real in Central Europe: The DIY Rap Music Careers of Male Hip Hop Artists in Austria.” Cultural Sociology 12(2):193–207.

Scott, Michael. 2012. “Cultural Entrepreneurs, Cultural Entrepreneurship: Music Producers Mobilising and Converting Bourdieu’s Alternative Capitals.” Poetics 40(3):237–255.

Sinigaglia, Jéremy. 2017. “A Consecration that Never Comes: Reduction, Adjustment, and Conversion of Aspirations among Ordinary Performing Artists.” Symbolic Goods: A Social Science Journal on Arts, Culture and Ideas (1):2–52.

Strachan, Rober. 2003. Do-It-Yourself: Industry, Ideology, Aesthetics and Micro Independent Record Labels in the UK. University of Liverpool.

------. 2007. “Micro-Independent Record Labels in the UK: Discourse, DIY Cultural Production and the Music Industry.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10(2):245–265.

Tarassi, Silvia. 2018. “Multi-Tasking and Making a Living from Music: Investigating Music Careers in the Independent Music Scene of Milan.” Cultural Sociology 12(2):208–223.

Threadgold, Steven. 2018. “Creativity, Precarity and Illusio: DIY cultures and 'Choosing Poverty'.” Cultural Sociology 12(2):156–173.

Weber, William. 2004. “The Musician as Entrepreneur and Opportunist.” In The Musician as Entrepreneur, 1700- 1914: Managers, Charlatans and Idealists, edited by William Weber, 3–24. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Wilkström, Patrick. 2009. The Music Industry: Music in the Cloud. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Notes

[1] The other types of invisible work that the authors talk about are the work of socialization, which will be discussed later; the work of routine, which concerns the incorporation, maintenance, and improvement of instrumental technique; and the work of inspiration, which encompasses different activities that supposedly stimulate creativity and instigate artistic creation, such as listening to music, going to exhibitions, reading, dreaming, travelling, and others.

[2] Considering only the 53 interviewees who perform the activity of musician, 29 are involved in more than one musical project.

[3] This pragmatic posture in the way of relating to music, understanding it as a full-time job and side-lining conceptions of music as a hobby or as pure entertainment, as well as the more romanticized perspectives of musical activity, is expressed by fifty-four percent of those interviewed. On the other hand, seven percent admit having a very emotional relationship with music and therefore find it very difficult to see it as a profession, assuming in some cases that they do not want to depend on it from a financial point of view. There is also a third group of interviewees (twenty percent), mainly young people, for whom music is above all a means of expression to transmit their message. They combine or imagine themselves soon combining music with other artistic languages, such as the fine arts or writing. Given the ambiguity that characterises the forms of relationship with music, in the case of the remaining interviewees (nineteen percent) it is not clearly perceptible how they see it, since they denote intersections between a more pragmatic vision and a more emotional one.

[4] About the centrality of these actors from the music world, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is interesting to mention their capacity for collective mobilization around the awareness of the importance of live music, namely among political decision-makers. This resulted in the constitution of Circuito — Associação Portuguesa de Salas de Programação e de Música (Portuguese Association of Programming and Music Venues), which gathers more than 20 venues, in mainland Portugal and on the islands, with independent and regular programming of concerts, DJ sets, and live acts, by national and international artists. The association’s main objective is to give visibility to the current independent circuit of popular music in Portugal, drawing attention to its cultural, economic, and social relevance and to the multiple professionals — artists, technicians, small agencies, promoters, and labels — that shape it. It, therefore, intends to include this circuit in the public and political debate and claim an active role for the State in its preservation, at a time when its sustainability is being threatened. To this end, it has already presented concrete proposals for support measures, defending the need to understand this circuit as culture, insofar as the work of these venues is based on a logic of cultural programming that, often, even integrates other artistic disciplines besides music.

[5] Most of the interviewees (sixty-six percent) belong to the middle class, associated with liberal professions in the artistic, intellectual, or scientific areas. Their advantage in terms of possession of economic, social, and educational capital is already present in their families of origin. Fifty-two percent of the interviewees’ mothers and fifty-eight percent of fathers have completed or attended higher education; Fifty-one percent of the interviewees have parents with intellectual and scientific professions; and twelve percent of interviewees’ parents are entrepreneurs, owners, or managers.