Impact and Hope for the Live Music Industry

I don’t know when it will be safe to return to singing arm in arm at the top of our lungs, hearts racing, bodies moving, souls bursting with life. But I do know that we will do it again, because we have to. It’s not a choice. We’re human. (Dave Grohl, 2020).

Live music, whether at a festival (Carneiro et al. 2011) or an indoor venue (Edwards et al. 2014), contributes to the economic development of its location. The COVID-19 pandemic has severely disrupted the live music industry and therefore the financial contributions of its participants. The present article investigates how the pandemic is affecting — and will affect — live music in the U.S. context. The pertinent elements of the industry and its players will be discussed, followed by the impact of the pandemic. This is followed by a discussion of how the live music industry has adapted, then how those adaptations may affect the future of the industry, including the results of a survey of contemporary music consumers. The article ends with research limitations and opportunities for future research.

Background: The concert industry

Live Music as a Primary Source of Revenue in the Music Industry

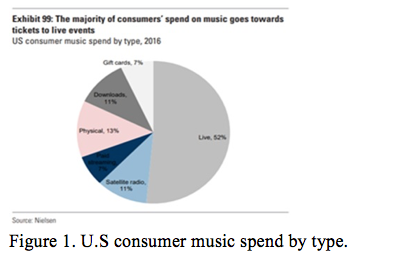

The three primary revenue streams in the music industry accounted for nearly $25 billion in revenue in North America in 2019: $3.72 billion in music publishing (Ingham 2020), $11.1 billion in recorded music (Rys 2020), and $9.4 billion in live music (Gensler 2019). The $9.4 billion of live music revenue in North America is up from $1.7 billion in 2000, with an all-time high of $12.2 billion having been projected in 2020 (Pollstar 2020). According to a Nielsen survey, over fifty percent of consumer spending on music is attributed to live events, citing the “live music experience” as a reason for the allocation (Music360 2016). Subsequently, the concert industry has experienced unprecedented growth, having emerged as a vital source of revenue for performing artists as well as consumer-based music experiences.

Growth of the Touring Industry

Three main factors, fueled by technology, led to the growth of the touring industry in North America over the past twenty years: a greater number of artists actively touring, likely related to the number of musicians who have entered the marketplace; the rising cost of concert tickets; and the growth of the festival marketplace in the U.S. The increase in artists is in part a consequence of technological advances having lowered the barrier to entry. Digital Audio Workstations (DAW), including GarageBand and Pro Tools, are readily available for artists to record music affordably. Digital distributors and streaming platforms allow for more music to be released by recording artists without competing for limited access to retail shelf space. Over thirty-five thousand albums were released in 2000 in North America, rising to nearly 80,000 albums in 2007 and 98,000 in 2009 (Stein 2010). Ten years later in 2019, Spotify founder Daniel Ek stated forty thousand tracks were uploaded to the platform every day, which is the equivalent of fourteen million six hundred thousand tracks, or one million four hundred sixty thousand albums released each year on Spotify alone (Ingham 2019). Technology directly relating to touring has also fueled this growth, allowing musicians and independent promoters to book, market, and execute live shows (Pittman 2019). Subsequently, more artists are releasing music and touring as a primary means to earning a living.

Also fueling growth of the touring industry are music festivals, which have exploded in the United States during the past twenty years. Over 800 music festivals were produced in the United States in 2017 with over thirty-two million people attending music festivals each year. About one-third of festival-goers (ten million two hundred thousand) attend two or more festivals per year and on average travel 900-plus miles to get to their festival destination (Deployed 2018). This growth and expansion of the music festival industry has been referred to by scholars as festivilization (Bennett, Taylor and Woodward 2014; Mulder, Hitters and Rutten 2020). Millennials’ spending power is estimated at over $1.3 trillion in the U.S., and three-quarters of them would rather spend money on an experience (Millennials 2017). Nearly seventy percent of millennials feel attending events makes them more connected to other people (Music360 2016), and there is evidence that it is important to individuals’ social identity (Packer and Ballantyne 2011).

Finally, in the United States the price of concert tickets has grown exponentially from 2005 to 2019, rising from $42.00 to $94.83 for the top 100 grossing tours, a one hundred twenty-six percent increase. The average gross revenue for a top 100 U.S. tour rose from $652,311 to $958,726 (a forty-five percent increase) from 2015 to 2019 (Gensler 2019). This unprecedented growth has led to intense competition from players in the marketplace, as discussed in the following sections concerning the economics of concert revenue, concert promoters, and booking agencies.

Economics of Concert Revenue

Concert promoters hire artists to perform at concert venues and assume full risk for the concerts, usually offering a guarantee to pay the artist. Concert promoters recoup expenses through revenue earned at the concert largely based on ancillary products including ticket fees, parking, merchandise, and concessions, with the artist receiving eighty-five to ninety percent of ticket revenue (Resnikoff 2011). A single concert ticket can represent additional spending of $25-50 from transportation, parking, gas, restaurants, and lodging (Pollstar 2020). Live music is a valuable asset to the cultural and economic status of many cities, attracting tourists to stimulate the local economy and help to enhance cultural environments (Hudson 2006; Martin 2017; Wynn 2015). From 2015 to 2019, ancillary revenue experienced eight percent growth, reaching $29.50 per fan in attendance for an event in 2019 (Jurzenski 2020). Festivals are particularly valuable to local economies; for example, the Coachella Music and Arts Festival region lost over $700 million dollars from that event’s 2020 cancellation (Perreault 2020).

Concert Promoters

The dominant market leaders in the concert promotion industry in North America are Live Nation and AEG Presents. Annually, Live Nation promotes over twenty-two thousand events (Live Nation n.d.) generating $11.55 billion in 2019 (IBIS 2020). Live Nation, which owns or operates over a hundred venues, including amphitheaters, theaters, clubs, arenas, and festival sites, derives the majority of its income from top 100 spring and summer tours taking place at these venues. Live Nation was originally formed in 1996 as SFX Entertainment, a subsidiary of SFX Broadcasting that was sold to Clear Channel Communications for $4.4 billion; in 2005, Clear Channel spun off its entertainment division and named the new company Live Nation, Inc. (Reference for Business 2019). Live Nation’s acquisition of several regional concert promoters and popular music festivals accelerated its growth and dominance in the United States. Live Nation acquired the House of Blues chain in 2006 (Leeds 2006), C3 Presents in 2014 (Faughnder 2015), Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival in 2015, and Founders Entertainment, parent company of Governors Ball Music Festival in 2016 (Sisario 2016). Subsequently, Live Nation has become the market leader in the concert industry, increasing revenue from $3.2 billion to $11.5 billion between 2005 and 2019 and achieving a twenty-four percent market share of the concert industry (Statista 2021a).

Live Nation is a vertically integrated, publicly traded company with several business divisions including concert promotion, ticketing, and artist management which enable them to leverage top tours and maintain market share of the concert industry. Concert promotion is the main driver of revenue for Live Nation, comprising eighty-two percent of revenue in 2019. In 2010, Live Nation merged with ticketing service giant Ticketmaster, which owned a seventy percent share of the concert ticket market in the United States in 2019. Live Nation’s artist management division, Artist Nation, represents over five hundred artists and currently has a forty percent market share of top-tier talent (Jurzenski 2020). Artist Nation’s growth has been attributed to acquisition and partnerships with a variety of affiliated companies (Ingham 2017).

Live Nation employs over ten thousand five hundred individuals and is publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange; its initial IPO was in 2005, and its stock was trading at $74.60 as of December 28, 2020 (Peters 2020). Its stock price took a hit during the coronavirus pandemic, plummeting in the third quarter after losing ninety-five percent of its revenue but recovered and jumped fifteen percent in November 2020, after Pfizer and BioNTech coronavirus vaccines were approved (Peters 2020). There is room for optimism about fans returning to live concerts, as over eighty-five percent of fans opted not to get refunded for concerts that were cancelled during the pandemic (Brooks 2020). In August 2020, Live Nation management told analysts the company believes 2021 and 2022 will be record years, and Barron’s reported that Live Nation stock could more than double in the next three years (Jurzenski 2020).

AEG Presents, the live-entertainment division of Los Angeles-based Anschutz Entertainment Group, is the second largest concert promoter in the United States. The Anschutz Corporation is a private company; therefore, financial data is not released to the public. IBIS (2020) projected AEG’s industry-relevant revenue to have increased at an annualized rate of nine point four percent from 2015 to 2019, totaling $2.2 billion in 2019. AEG has several subsidiaries in the concert and event promotion industry, including AEG Live and Goldenvoice. AEG produces over ten thousand concerts and twenty-five music festivals a year, and operates three hundred venues (AEG n.d.) including the Staples Center, the Toyota Sports Center, the StubHub Center; it also produces the Grammy Awards, the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, and the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival (IBIS 2020).

In 2019, Live Nation sold forty-six million six hundred thousand concert tickets, and AEG sold 14.8 million concert tickets, owning a twenty-three point nine percent and six point nine percent market share of the industry in the U.S., respectively (Promoters 2019). The third- and fourth-largest concert promoters fared well behind the market leaders, selling four million six hundred thousand and three million two hundred fifty thousand tickets, respectively (Statista 2021b). Brennan and Webster (2011:17) point out “[t]he growth of corporate concert promotion, Live-Nation style, is bound to have effects on the ecology of live music. If the live music sector is to be sustained, new talent must develop, and for this to happen, venues are needed for new ‘amateur’ artists as well as for established professionals.” Outside of the two dominant concert promotion leaders, the concert industry is fragmented into thousands of independent promoters participating on regional and local levels. Independent promoters benefit from the opportunity to build strong relationships with artists and venues, enjoy greater flexibility than large multinational companies, and have a reputation for being more entrepreneurial (Pittman 2019).

Booking Agencies

Booking agents not only play a pivotal role building and maintaining a lasting career for artists, but also serve as a talent pipeline for concert promoters. In the traditional organizational structure of the live music industry, booking agents are the intermediary between the artist and the concert promoter. Promoters invest in up-and-coming artists who have been endorsed by agents at the start of their careers, betting that eventually they will be able to sell out larger rooms (Behr et al. 2016). The relationship between agent and promoter can be a huge advantage for those artists with representation; for artists who do not have an agent, it can be a much harder process to get the attention of a concert promoter. As Rogers (2010:643) points out, “independent touring is a process of negotiation, networking, and trade.” An independent artist does not have an intermediary working on their behalf and benefiting from a prior relationship with the concert promoter. Furthermore, most established promoters who are booking larger rooms will only book artists though their agents and will not book artists who lack representation. Webster (2011:132) argues these relationships are essential for venue owners, stating “if they have a good relationship with an agent, they will have access to the agent’s roster and most lucrative acts. Consequently, promoters must accumulate social capital with agents in two ways: first, by doing a good job on the tour; and second, by maintaining a personal relationship with the agent.”

At the time of this writing, the three largest full-service booking agencies in the U.S. are William Morris Endeavor, Paradigm, and Creative Artists Agency, with Paradigm claiming to be the largest for music acts. Paradigm went through an acquisition strategy in order to expedite growth by acquiring several smaller to mid-sized booking agencies such as Monterey Peninsula Artists, Little Big Man, The Windish Agency, and AM, as well as purchasing a fifty percent stake in the international firm Coda Agency in 2017. These acquisitions allowed Paradigm to diversify and establish a roster of household names and up-and-coming artists in a relatively short time. Having representation from a large roster gives each of these agencies a competitive advantage. If a promoter wants to book a top-tier act from one of these agencies, oftentimes the agent will leverage the deal with the promoter in order to book one of their unknown bands as well, evidence that the existing relationships with intermediaries play a vital role in the success of an artist. These three agencies created almost exclusive relationships with Live Nation and AEG, and in 2010 the festival Lollapalooza (promoted by C3/Live Nation) was the subject of an antitrust investigation (Knopper 2010).

However, the pandemic’s effect on the live music industry may adjust the dominance of the three major agencies and change the organization of this side of the music business. Amidst the halt of live shows, Paradigm terminated nearly two hundred agents (Rendon 2020). Many of these agents who were let go then started their own independent booking agencies with high-profile clients, which may have leveled the playing field. While relationships will still play a key role in how an artist gets booked for a show, the pipeline may have been redirected, with the two largest concert promoters no longer exclusively doing business with the three largest booking agencies. This is a phenomenon that will be of great interest to both theory and practice as the U.S. music industry emerges from the pandemic. Independent promoters have said they do not feel they were squeezed out by the size and dominance of the large-scale agencies (Pittman 2019). However, one need only view the lineup for a festival like Coachella to understand the enduring influence of the big three booking agencies.

According to the National Independent Venue Association (NIVA), ninety percent of independent music venues expected they would have to close permanently if no federal funding was made available by February 2021 (NIVA 2020). The economic impact has affected many stakeholders of the live music industry, putting at risk not only jobs but entire careers of musicians and other performers who are not in the limelight, in turn leading to a cultural void (Cohen 2020). Of particular interest for the present article is the impact on booking agencies, live event production crews, and artists and their teams. Goldman Sachs (2020) predicts a seventy-five percent drop in live music revenue only partially offset by an eighteen percent increase in music streaming revenue. Of particular importance to the industry are metropolitan areas relying on live music to help fuel their economy. For example, Nashville, TN which has a prominent live music scene has seen a loss of seventy-two percent in overall revenue and seventy-three point five percent employment (Nashville 2020). This same report warns that the pandemic has so endangered the live music industry that many venues and related businesses face permanent closure. The timing of the Nashville report (2020) is such that it serves as a reflection of what the live music industry in cities throughout the United States may experience and deal with. Groups like the Record Industry Association of America through Music COVID Relief (RIAA 2020) and NIVA have organized relief efforts for the live music industry, and additional relief has been provided by the Save Our Stages act passed by Congress (SOS 2020). Still, there are questions about whether these relief efforts will be enough to get the live music industry back on its feet (Gensler 2020).

The impact on booking and ticketing agencies is apparent, with an eighty-one percent loss in revenue during the first three quarters of 2020 for industry powerhouse Live Nation (Tschmuck 2020). Live Nation set up the “Crew Nation” relief effort, pledging $10 million in support of COVID-19 relief for production crews (Millman 2020). Artists have also gotten in on the act, with plans for post-pandemic policies, even though some have been met with mixed reception from fans (Smith 2020).

Randy Nichols, President of Force Media Management (FMM), indicated during a video conference conversation specifically for this article (Nichols 2020) that artists have experienced their largest financial impact from the live music shutdown. He stated that while the early days of the pandemic brought signs of complete disaster, livestreams created an opportunity to partially offset the impact. For example, one of the acts managed by FMM, Underoath, engaged in livestream concerts that brought in more revenue than would have been expected from a summer tour. Furthermore, other marketing activities surrounding the livestream events such as vinyl reissues related to the livestream content helped keep the band’s overall revenue for the year down only about thirty-forty percent, as opposed to a hundred percent reduction, as they initially expected.

Adaptation of the Touring Industry

As discussed in the July 2020 New York Times feature story “Concerts Aren’t Back. Livestreams are Ubiquitous. Can They Do the Job?” the pandemic incited an explosion of at-home livestream performances broadcasting via social media portals. The website Bandsintown.com tracked over sixty thousand livestream performances by nearly twenty thousand artists, growing from a hundred thirty-nine performances per day in March to three hundred nineteen in May. The number of livestream concerts declined in summer 2020 and gradually increased again during October, November, and December of 2020 (Frankenberg 2020).

The Internet has provided plenty of opportunities to see live music during the pandemic through channels from Instagram to Twitch, and by artists from Elton John to Neil Young (D’Omodio 2020; Frank 2020; Frankenberg 2020; Peisner 2020; Peters 2020). In addition, a growing number of livestream music services have begun creating ticketed events to enable artists to monetize virtual performances.

Livestreaming brings both positives and negatives for the consumer and artist. Artist expenses are lower without travel and accommodations, and it is less costly to put on a livestream than an in-person tour. While many artists can instantly stream from their computer or mobile device, it remains a challenge to engage the fan from the comforts of their home when so much of attending a concert is about communal engagement with a crowd. Ben Gibbard, front man for the band Death Cab for Cutie, who livestreamed from his home regularly from mid-March through May stated, “The Pavlovian response for the past twenty-three years is you finish a song and whatever number of people are in the room clap for you … I’ve gotten used to that being the validation” (Peisner 2020).

Livestreaming challenges the notion of what most live music industry scholars argue is the main appeal of attending a concert. Cloonan (2020) points out that the value in attending a concert is the experience the attendees have in a venue, which is what allows artists to command such high ticket prices. For livestreaming concerts to be successful, they may need to feel just as, if not more exciting than their real-life counterparts. If artists are able to take the concept of community a step further and provide levels of proximity to both artists and fellow fans that are not possible in person (Grasmayer 2020), we may see a completely new concert industry. Many fans attend shows because of the community they find within the shared fandom of an artist, as is the case for fans of American musician Bruce Springsteen:

Springsteen fans form a community; they share a sense of identity, which is reaffirmed by going to the shows, by taking advantage of opportunities to socialize with other members of the tribe, sometimes to meet up with people who are otherwise contacted only online (Cavichi 1998:164–165).

According to industry coverage (Empire 2020; Havens 2020), performer Billie Eilish set a high standard for virtual concert performance with her performance of Where Do We Go? The Livestream. This experience established “place” by creating multiple rooms where fans could interact, and virtual shopping experiences for merchandise. Furthermore, Eilish used technology to interact with her fans and create a community that exceeded what is possible in a traditional venue, and five hundred pre-selected fans were able to interact with her prior to and during the concert. This experience created a sense of space that was intimate and (virtually) interactive. The band Underoath studied other bands’ livestreams before designing their own. What in a live show would have been stage management became designing the space being used for the performance, to foster a sense of intimacy — of being in the room with the musicians, as opposed to looking at a concert stage, according to FMM’s Nichols. From a more theoretical perspective, we see this as a current and possibly continuing dimension of “place” when it comes to live music consumption.

While elements of a music venue are constructed to contribute to the authenticity of a live show (Carah et al. 2020; Robinson and Spacklen 2019; Moore 2007), the innovations used to create a virtual experience for fans during the pandemic may contribute to what constitutes authenticity of live performance in a virtual world. We find parallels to this in authenticity literature, where some researchers point to the necessity of physical, historical structures for conveying authenticity (Alberts and Hazen 2010; Rössler 2008), while others assert that authenticity in music can be found instead in its intangibles, such as tradition (Knox 2008), symbolism (Shusterman 1999), and lyrics (Cheyne and Binder 2010). Even outside the parameters of livestreaming during the pandemic, there are similar findings by researchers about innovations in technology used to enhance recordings for the benefit of consumers (Zagorski-Thomas 2010) and the changing nature of “place” in music authenticity (Stanton and Schofield 2021).

Future of the Touring Industry

As the live music business enters a post-pandemic world, it will include elements of pre-pandemic days as well as necessary changes. These changes, whether minor (e.g., requiring event attendees to provide proof of vaccination (Smith 2020)) or major, could help the live music industry climb out of the hole it was thrown into. To understand these changes, we can take cues from adaptations made during the pandemic, and from our knowledge of music consumers.

The single most important pivot from the perspectives of the music fan and artist is the reliance on livestream concerts. Livestream music has been around for a long time, even as early as the late 1990s (Carrell 1999), but it was brought to prominence during 2020 due to the shutdown of in-person concerts. FMM’s Nichols indicates that he sees Americans’ comfort with livestream events as an opportunity to increase the reach of future in-person tours, where only about five percent of an artist’s fan base is traditionally reached. With the attention being paid to the technological innovation of livestreaming, and the evolutionary nature of what constitutes authenticity in music venues as discussed above, post-pandemic music consumption may include a stronger livestream element.

Fully emerging from the pandemic will take some time. Independent music venue operators overseeing small to mid-sized clubs need several months of lead time to re-open and will not be able to operate profitably on a limited capacity basis (Munslow 2020). As a result, artists might have to play more shows and charge a higher ticket price when returning to live concerts (Horan 2020), but how much should performers charge for a complementary livestream when in-person shows return (Willman and Aswd 2021)?

As we re-enter live concert spaces, there will be a massive shift in the ecology of performance, with technology playing a key role. As Behr et al. (2016) note, “one essential difference between listening to live performance and listening to recorded performance is that the former is spatially and temporally specific.” As artists continue to experiment with new ways of connecting with their fans in a way to mimic live performance, is a virtual stream capable of evoking the same experience? While we believe consumers will be eager to get back to concerts and festivals, and continue to believe live events is an attractive market with a number of demand- and supply-side tailwinds, we expect the growth of livestreaming to be more complementary than cannibalistic to the industry, as this will likely be the “new normal” for quite some time.

Additionally, artists have begun to partner with gaming platforms such as Fortnight, Minecraft and Twitch. The global gaming industry generated over $150 billion in sales in 2019 (Morgan Stanley 2020) and continues to see growth during the pandemic. Travis Scott reportedly earned over $20 million gross for his performance on Fortnight (Brown 2020). If artists with large followings start thinking about those platforms not just as revenue-generating alternatives to live concerts but as a way to reimagine the very idea of what a concert is, this could be another large source of revenue. A potential way to continue to use livestreaming components once venues re-open is to gamify the virtual experience to further engage with an audience. As Danielsen and Helseth (2016) found, audience experience is enhanced by visuals, as long as they are consistent with the auditory elements.

Technology can help provide a safe experience for artists, fans, and staff, allowing opportunities for additional revenue for the promoter and artist, both virtually and in-person. For AEG, the main focus on the return to live music is to make as much of the experience as “contactless” as possible (Hissong 2020a) through elements such as mobile device tickets and in-venue purchases for concessions and merchandise, a key source of revenue. As we think about what it may look like to hold concerts in venues once again, there are some harsh realities that must be considered. The deal structure between the artist and promoter may need to change in order to spread some of the risk to the artist. The traditional deals that were standard in the live industry, such as the guarantee versus a percentage deal of having the artist earning eighty percent to ninety-five percent of net income alongside a guarantee or minimum fee, may need to change. Live Nation in particular is attempting to have the artist share in some of the risk of putting on festivals when they return and incorporate livestreaming as a required component of their performance agreement. In a memo that was sent to all the major booking agencies, Live Nation noted that artist guarantees would be adjusted downward by as much as twenty percent; artists would be required to stream their festival performance online; if an artist’s performance is cancelled because of an event of force majeure (including a pandemic) the promoter will not pay the artist; and if the artist cancels their agreement and is found in breach of contract, they will be liable to pay the promoter double their agreed-upon fee (Hissong 2020b). Clearly the stakes are higher than they have ever been before for both artists and promoters. Jay Marciana, CEO of AEG, noted the incongruence of concerts with social distancing, as quoted by Hissong:

The concert business doesn’t function well in a socially distanced manner. “We built an industry based upon selling out. … The first fifty percent of the tickets pay for expenses like the stagehands and the marketing, the ushers, and the rest and the venue, and the other fifty percent is shared between the artists and the promoter — so, if all you’re going to sell is fifty percent of tickets, nobody’s making any money. Selling eighty-five percent of tickets is roughly the break-even” (Hissong 2020a).

In venues like arenas, it’s simply not cost-effective to go through the expense of producing a show that can only sell fifty percent of the seats; in clubs and smaller theaters, AEG expects a “gradual ease” back into things, with some reduced-capacity shows (ibid.).

Clearly the economics of producing a show at limited capacity significantly reduces the amount of income generated. The lower profit margin would therefore be felt by the consumer as ticket prices are raised to cover expenses. Furthermore, would an artist who regularly sold out arenas before the pandemic want to play to a half-sold room in order to abide by social distancing guidelines? How does attending a concert in a half-empty room affect the experience? Additionally, for the artist and agent, trying to book a tour before the pandemic was already a complicated process of searching for venue availability along a particular route. As venues reopen on different timelines, trying to book a successful tour might not be financially feasible as artists try to patch together shows in cities where they are able to play. This, in combination with the proposed fee reductions for artists, could lead to them having to perform more shows in order to try and achieve their pre-pandemic revenue.

Consumer Perspective

Given the growth of livestreaming and its potential in a post-pandemic U.S., the authors conducted a web-based survey exploring the perception of live music and livestream by contemporary music consumers.

Methodology

Qualtrics software was used to create a brief web-based survey that was distributed using snowball sampling through social media and via email, and analysis was conducted using SPSS Version 22. Respondents were asked to answer basic questions about their perceptions of livestream music, their likelihood to view as well as pay for livestream music, and about their engagement with livestream music before and during the pandemic, as well as their views related to appreciation for live music. Age, gender, and preferred genre were also gathered from respondents. The survey was clicked on by three hundred one respondents, of which thirty-two were removed for having submitted incomplete data, yielding two hundred sixty-nine usable cases. Of these cases, each of the recognized generational categories were represented; forty-five self-reported as being born between 1946 and 1965 (baby boomers); eighty-two between 1965 and 1980 (Generation-X); sixty-nine between 1981 and 1996 (Generation Y/Millennials); sixty-eight after 1996 (Generation Z); two before 1946; and one respondent did not answer this question. Self-reported gender was fairly evenly distributed with a hundred twenty-five males, a hundred thirty-nine females, three non-binary/third gender, and two respondents who selected “prefer not to respond.”

Findings

Supporting the opinion of FMM President Randy Nichols, participants in the survey indicated that the pandemic has increased the comfort level of viewing a livestream event. Seventy-four (twenty-eight percent) of two hundred sixty-nine participants self-reported that they had not viewed a livestream event prior to the pandemic; however, a hundred sixty-five (sixty-one percent) reported that they viewed such an event during the pandemic. Accessibility of livestream shows in the future may be aided by industry participants, such as a recently launched subscription service by the website Bandsintown.com (Willman 2021).

The question remains whether American music consumers will be willing to pay for livestream music, even if it is because there are no nearby venues during a tour. When survey respondents were asked whether they were just as likely to view a livestream of their favorite musician as they would be to go to a live show, the results using a six-point Likert-type scale yielded a distribution close to normal, with fifty-five percent agreeing, and forty-seven percent disagreeing (n=269; 3.63 mean / 1.5 standard deviation). However, when the same respondents were asked whether they would be just as likely to pay for a livestream of their favorite musician as they would to attend a live show, the distribution skewed toward disagree (less likely to pay), with only thirty-five percent agreeing, and sixty-five percent disagreeing (n=269; 2.91 mean / 1.47 standard deviation).

Anecdotally, there has been a general belief that younger generations might be more inclined to view a livestream event, likely because there is a general consensus and some potentially supportive data, that millennials are at the heart of the live music industry (Miles 2018). However, one cannot assume that just because younger music consumers are associated with live music that there is a similar indication of perceptions of live music and livestreams during the pandemic.

Looking at statistically significant differences between baby boomers born before 1965 and younger generations we found some interesting results. First, baby boomers reported they were more likely to view a livestream of their favorite musicians than were millennials (mean of 3.83 vs. 3.28 on a six-point Likert-type scale; p < .05). The data also indicate statistically significant differences when answering a question about how much they miss live music, with baby boomers reporting they miss it more than respondents from both Generation X (mean of 4.83 vs. 4.68; p < .05) and Generation Z (4.83 vs. 4.4; p < .05). Furthermore, a multiple regression analysis, where the dependent variable is “I am just as likely to pay for a livestream of my favorite musician as I am to pay for their live show” revealed only two statistically significant independent variables: likelihood to view a livestream and age group, where the coefficient of age group indicated that older age groups were more likely to pay for a livestream (Model R2 = .49; p < .001) than lower age groups.

We believe our results can be attributed to two basic lines of reasoning. First, older generations may have more disposable income and/or equity and were therefore more likely to pay for a livestream during the pandemic. Second, the increasing accessibility of livestreams may have been a novel experience during the pandemic. Novelty of livestreaming is an area that is ripe for future research, with opportunities for data collection and assessment as the live music industry recovers from the pandemic. It is important to note that just because respondents answered questions about their perceptions during the pandemic doesn’t necessarily indicate that these perceptions will carry forward to a post-pandemic environment. It does, however, indicate that there may be an opportunity to target an older audience differently from a younger audience, in particular through re-enchantment of live music.

Two important elements of music consumers will be of great importance to how the live music industry returns: contemporary consumers’ engagement with music, and a theory that consumer behaviorists have borrowed from psychology — psychological reactance. As we consider these two important elements, we find that the post-pandemic live music industry presents an opportunity for encouraging re-enchantment of music for live music attendees.

Chamorro-Premuzic and Furnham (2007) explored the ways in which consumers used music, initially indicating that “social use” was a background use of music. However, Barretta (2014) found evidence that social use of music was a primary, not background use, meaning that contemporary society uses music as a tool of social interaction, not just something that exists in the background of our everyday lives. COVID-19 appeared during music’s increasing use as a social tool. Live music venues are clearly places where consumers engage in the social use of music, planning outings around a live music event — be it for a one-night symphony concert or a three-day music festival. Before the pandemic, when live music opportunities were all around us, music consumers had freedom of choice to experience live music of many genres in all types of venues. What happens when this freedom of choice is taken away?

According to psychological reactance, threats to a person’s freedom, in this case freedom to attend a live music event, will cause a desire to reassert that freedom through action; furthermore, the more the freedom is denied, the greater the overreaction (Clee and Wicklund 1980). In the case of having limited substitutes for in-person live music consumption, which is the state caused by the pandemic, re-opening of venues, and eventually festivals, will empower the live music industry to indulge music consumers’ reaction to having lost their freedoms of choice to view live music.

The overall societal state we find ourselves in also gives some direction for how to encourage a return to live music; we can take cues from how researchers have treated music in the contemporary view of consumers living in our postmodern condition. A very important element of understanding contemporary consumers and music is described by Garcia (2011:270) as having “the ability to re-enchant the world again, repeatedly against the threat of mechanization of human life on earth.” While Garcia used this description to describe the power of music and poetry to overcome the disenchantment of life as written about by Max Weber, other researchers have focused on the power of music to capture the re-enchantment of human lives, as addressed by Firat and Venkatesh (1995). For example, Leaver and Schmidt (2010:121) write about the power of music to experience a “lasting sense of ‘magic’ and re-enchantment.” Jennings (2010:82) writes of music spaces, “(w)hether they facilitate transformation of the world, or simply open a portal to a temporary escape, these realms are both popular and necessary in modern cultures.” Similarly, particular to live music, Holt (2010) argues that the current “restructuring of the economy of music is to a high degree related to factors beyond the music itself, especially the qualities of live experience, but also the social conditions of media and capitalism and postmodern narratives of self-realization through cultural consumption.” Our assertion with this article is that live music can be one of those places provided to a society hungry for re-enchantment of the world as it emerges from the pandemic.

In this same light, using a theoretical foundation of psychological reactance, providing the opportunity for a return to live music experiences can be an opportunity for consumers to regain their freedom to experience live music performances, consistent with how freedom is defined by Clee and Wicklund (1980), while also using music as a source of re-enchantment, consistent with contemporary society.

Limitations and Future Research

Some of what is presented above contains prophetic statements based not only on existing theory, but on a state of society at the time of its writing that is quickly changing as the United States continues to find its way toward a post-pandemic state. The results of the primary research on music consumers is statistically sound, though is a cross-sectional study in a rapidly changing society. This yields a very interesting opportunity for future research to investigate longitudinal differences in public perception.

In addition to the questions raised in the Future of The Touring Industry section, other industry questions emerge that are ripe for future research. Will the proliferation of new agencies established by former employees of major agencies level the playing field and give independent artists more leverage? Will these new agencies be more artist-centric, or will they operate with the same ethos as larger organizations? We are beginning to see a potential redistribution of power and influence on the promoter side. Both independent artists and those with representation are dependent on the ecosystem of smaller independent venues and larger rooms. With the prolonged period of no revenue, many smaller venues have feared for their survival. A number of notable independent venues have had to close, including Boot and Saddle in Philadelphia, The Satellite in Los Angeles, and Great Scott in Boston, to name a few. With a diminishing environment for independent artists to cultivate a fan base, agents and promoters will find it difficult to groom artists into performers that can potentially sell out an arena. Marc Geiger, former William Morris Endeavor head of music and co-founder of Lollapalooza, started SaveLive in an attempt to bail out the struggling independent venues (Sisario 2020). This would seem like a positive step for independent artists and venues; however, will this consolidation of power in independent venues simply create another behemoth concert promoter that will limit the potential growth and scale of up-and-coming artists? These are the types of questions that will loom large as the post-pandemic music industry takes off.

References

AEG Worldwide Music. AEG. https://www.aegworldwide.com/divisions/music. (Accessed December 2 2020).

Alberts, Heike C., and Helen D. Hazen. 2010. “Maintaining Authenticity and Integrity at Cultural World Heritage Sites.” Geographical Review 100(1):56–73.

Barretta, Paul G. 2014. “Perceived Creative Partnership: A Consequence of Music’s Social Use.” Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 75(2)–A(E)).

Behr, Adam, Matt Brennan, Martin Cloonan, Simon Frith, and Emma Webster. 2016. “Live Concert Performance: An Ecological Approach.” Rock Music Studies 3(1):5–23.

Bennett, Andy, Jodie Taylor, and Ian Woodward, eds. 2014. The Festivalization of Culture, Farnham: Ashgate.

Brennan, Matt, and Emma Webster. 2011. “Why Concert Promoters Matter.” Scottish Music Review 2(1):1–25.

Brooks, Dave. 2020. “Live Nation Says 86% of Fans Declined a Refund. Here’s What that Number Really Tells Us.” Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/9430533/live-nation-86-percent-declined-refund-behind-the-statistic. (Accessed August 6 2020).

Brown, Abram. 2020. “How Hip-Hop Superstar Travis Scott Has Become Corporate America’s Brand Whisperer.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/abrambrown/2020/11/30/how-hip-hop-superstar-travis-scott-has-become-corporate-americas-brand-whisperer/?sh=4f4b943474e7. (Accessed November 30 2020).

Carah, Nicholas, Scott Regan, Lachlan Goold, Lillian Rangiah, Peter Miller, and Jason Ferris. 2020. “Original Live Music Venues in Hyper-Commercialised Nightlife Precincts: Exploring how Venue Owners and Managers Navigate Cultural, Commercial and Regulatory Forces.” International Journal of Cultural Policy:1–15.

Carneiro, Maria Joao, Celeste Eusebio, and Marisa Pelicano. 2011. “An Expenditure Patterns Segmentation of the Music Festivals’ Market.” International Journal of Sustainable Development 14(3):290–308.

Carrell, Lawrence. 1999. “Digital Club Network Sees Gold In Archived Music Performances.” Wall Street Journal Interactive Edition. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB934920130869063921. (Accessed March 15 2020).

Cavicchi, Daniel. 1998. Tramps Like Us: Music and Meaning among Springsteen Fans. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas, and Adrian Furnham. 2007. “Personality and Music: Can Traits Explain how People Use Music in Everyday Life?” British Journal of Psychology 98(2):175–185.

Cheyne, Andrew, and Amy Binder. 2010. “Cosmopolitan Preferences: The Constitutive Role of Place in American Elite Taste for Hip-Hop Music 1991–2005.” Poetics 38:336–364.

Clee, Mona A., and Robert A. Wicklund. 1980. “Consumer Behavior and Psychological Reactance.” Journal of Consumer Research 6(4):389–405.

Cloonan, Martin. 2020. “Trying to Have an Impact: Some Confessions of a Live Music Researcher.” International Journal of Music Business Research 9(2):58–82.

Cohen, Patricia. 2020. “A ‘Great Cultural Depression’ Looms for Legions of Unemployed Performers.” New York Times.

Danielsen, Anne, and Inger Helseth. 2016. “Mediated Immediacy: The Relationship between Auditory and Visual Dimensions of Live Performance in Contemporary Technology-Based Popular Music.” Rock Music Studies 3(1):24–40.

Deployed. 2018. “The Rising Trends of Music Festivals in the U.S.” Deployed Resources. https://www.deployedresources.com/blog/special-events/the-rising-trends-of-music-festivals-in-the-u-s/. (accessed 13 June 2018).

D’Omodio, Joe. 2020. “Live Nation Brings Concert-Goers ‘Live from Home’ Dite.” SI Live. https://www.silive.com/entertainment/2020/04/live-nation-brings-concert-goers-live-from-home-site.html. (Accessed April 1 2020).

Edwards, Deborah, Carmel Foley, Larry Dwyer, Katie Schlenker, and Anja Hergesell. 2014. “Evaluating the Economic Contribution of a Large Indoor Entertainment Venue: An Inscope Expenditure Study.” Event Management 18(4):407–420.

Empire, Kitty. 2020. “Billie Eilish: Where Do We Go?: The Livestream Review – Feel the Fear…” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/oct/31/billie-eilish-where-do-we-go-livestream-concert-review. (Accessed October 31 2020).

Faughnder, Ryan. 2015. “Live Nation Entertainment Buys Controlling Stake in Bonnaroo Festival.” Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/envelope/cotown/la-et-ct-live-nation-buys-controlling-stake-in-bonnaroo-20150428-story.html. (Accessed March 15 2020).

Firat, A. Fuat, and Alladi Venkatesh. 1995. “Liberatory Postmodernism and the Reenchantment of Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 22(3):239–267.

Frank, Allegra. 2020. “How ‘Quarantine Concerts’ are Keeping Live Music Alive as Venues Remain Closed.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/culture/2020/4/8/21188670/coronavirus-quarantine-virtual-concerts-livestream-instagram. (Accessed April 8 2020).

Frankenberg, Eric. 2020. “The Year in Livestreams 2020: Bandsintown Data Shows Promise for Growth in 2021.” Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/chart-beat/9500729/year-in-livestreams-2020-bandsintown-data-growth-2021/. (December 16 2020).

Gallan, Ben. 2012. “Gatekeeping Night Spaces: The Role of Booking Agents in Creating ‘local’ Live Music Venues and Scenes.” Australian Geographer 43:35–50.

García, José M. González. (2011). Max Weber, Goethe and Rilke: The Magic of Language and Music in a Disenchanted World. Max Weber Studies, 11(2):267–288.

Gensler, Andy. 2019. “2019 Business Analysis.” Pollstar. https://www.pollstar.com/Chart/2019/12/BusinessAnalysis_792.pdf. (Accessed December 16 2019).

Gensler, Andy. 2020. “Not Saved By Save Our Stages: Majority of Live Business Will Not Benefit From New Relief Bill.” Pollstar. https://www.pollstar.com/article/not-saved-by-save-our-stages-majority-of-live-business-will-not-benefit-from-new-relief-bill-147062?curator=MusicREDEF. (Accessed December 30 2020).

Goldman Sachs. 2020. “The Show Must Go On.” Goldman Sachs Equity Research. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/infographics/music-in-the-air-2020/report.pdf. (Accessed May 14 2020).

Grasmayer, Bas. 2020. “Better Than Real Life: 8 Generatives.” Musicx. https://www.musicxtechxfuture.com/2020/08/03/8-generatives-better-than-real-life/. (Accessed August 3 2020).

Grohl, Dave. “The Day The Live Concert Returns.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/05/dave-grohl-irreplaceable-thrill-rock-show/611113/. (Accessed Nov 13 2020).

Havens, Lyndsey. 2020. “Billie Eilish Blows Minds With ‘Where Do We Go?’ Livestream: Recap.” Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/pop/9472436/billie-eilish-where-do-we-go-livestream-concert-recap/. (Accessed October 24 2020).

Hissong, Samantha. 2020a. “New Venues, High-Tech Concerts: AEG’s Plan to Come Out of Covid Stronger Than Ever.” Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/pro/features/aeg-concerts-covid-contactless-tickets-1098263/. (Accessed December 9 2020).

Hissong, Samantha. 2020b. “Live Nation Wants Artists to Take Pay Cuts and Cancelation Burdens for Shows in 2021.” Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/pro/news/live-nation-memo-pay-cuts-covid-1016989/. (Accessed June 17 2020).

Holt, Fabian. 2010. “The Economy of Live Music in the Digital Age.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 13(2):243–261.

Horan, Shan Dan. 2020. “OP-ED: Here’s what Shows Could Really Look Like when They Finally Return.” Alternative Press. https://www.altpress.com/features/live-shows-music-industry-future-opinion/. (Accessed August 14 2020).

Hudson, Ray. 2006. “Regions and Place: Music, Identity and Place.” Progress in Human Geography 30(5):626–634.

IBIS. 2020. “Covid-19 Impact Update – Concert & Event Promotion Industry in the US.” IBIS World. https://www.ibisworld.com/united-states/market-research-reports/concert-event-promotion-industry/. (Accessed November 30 2020).

Ingham, Tim. 2017. “Live Nation Companies Now Manage More than 500 Artists Worldwide.” Music Business Worldwide. https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/live-nation-companies-now-manage-500-artists-worldwide/. (Accessed February 27 2017).

------. 2019. “Nearly 40,000 Tracks are Now Being Added to Spotify Every Single Day.” Music Business Worldwide. https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/nearly-40000-tracks-are-now-being-added-to-spotify-every-single-day/. (accessed 29 April 2019).

------. 2020. “US Publishers pulled in $3.7BN during 2019 – Just Over Half What Record Labels Made.” Music Business Worldwide. https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/us-publishers-pulled-in-3-7bn-during-2019-just-over-half-what-record-labels-made/. (Accessed June 11 2020).

Jennings, Mark. 2010. “Realms of Re-enchantment: Socio-cultural Investigations of Festival Music Space.” Perfect Beat 11(1):67–83.

Jurzenski, Christine. 2020. “Live Nation Stock Can More Than Double in 3 Years, Analyst Says.” Dow Jones & Company. https://www.barrons.com/articles/live-nation-stock-can-more-than-double-in-three-years-analyst-51586380765. (Accessed April 8 2020).

Knopper, Steve. 2010. “Attorney General Investigates Lollapalooza.” Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/attorney-general-investigates-lollapalooza-233557/. (Accessed June 25 2010).

Knox, Dan. 2008. “Spectacular Tradition: Scottish Folksong and Authenticity.” Annals of Tourism Research 35(1):255–273.

Leaver, David, and Ruth Ä. Schmidt. 2010. “Together Through Life – an Exploration of Popular Music Heritage and the Quest for Re-Enchantment.” Creative Industries Journal 3(2):107–124.

Leeds, Jeff. 2006. “Big Promoter to Acquire House of Blues.” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/06/business/media/06music.html#:~:text=Live%20Nation%2C%20the%20nation’s%20biggest,of%20the%20live%2Dmusic%20business. (Accessed July 6 2020).

“Live Nation Entertainment.” https://concerts.livenation.com/h/about_us.html. (Accessed December 4 2020).

Martin, Declan. 2017. “Cultural Value and Urban Governance: A Place for Melbourne’s Music Community at the Policymaking Table.” Perfect Beat 18(2):110–130.

Miles, Kristen. 2018. “Millennials Drive Live Music Industry.” Branded. https://gobranded.com/branded-poll-millennials-driving-growth-in-live-music-industry/. (Accessed November 21 2020).

Millennials. 2017. “Eventbrite Research: Millennials Fuel the Experience Economy Amidst Political Uncertainty.” Eventbrite. https://www.eventbrite.com/blog/press/press-releases/eventbrite-research-millennials-fuel-the-experience-economy-amidst-political-uncertainty/. (Accessed June 16 2017).

Millman, Ethan. 2020. “Aerosmith, BTS, U2 Among Contributors to Live Nation Charity Fund.” Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/pro/news/crew-nation-fund-raises-15-million-1042608/. (Accessed August 12 2020).

Moore, Ryan. 2007. “Friends Don’t Let Friends Listen to Corporate Rock. Punk as a Field of Cultural Production.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 36(4):438–474.

Morgan Stanley. 2020. “The Global Gaming Industry Takes Centre Stage.” Morgan Stanley https://www.morganstanley.com.au/ideas/the-global-gaming-industry. (Accessed August 26 2020).

Mulder, Martijn, Erik Hitters, and Paul Rutten. 2020. “The Impact of Festivalization on the Dutch Live Music Action Field: A Thematic Analysis.” Creative Industries Journal 14(3):245–268.

Munslow, Julia. 2020. “How the Coronavirus Could Change the Live Music Industry for Good.” Yahoo! https://news.yahoo.com/how-the-coronavirus-could-change-the-live-music-industry-135916292.html. (Accessed September 6 2020).

Music360. 2016. “Music 360 – 2016 Highlights.” Nielsen. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/report/2016/music-360-2016-highlights/#. (Accessed September 23 2016).

Nashville. 2020. “2020 Music Industry Report.” Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce; Exploration.

Nichols, Randy. 2020. Video conference personal interview. Dec. 22 2020.

NIVA. 2020. “NIVA Includes more than 2,900 Independent Live Entertainment Venues and Promoters from All 50 states and Washington, D.C., Banding Together to Fight for Survival.” National Independent Venue Association. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e91157c96fe495a4baf48f2/t/5fab1f2d9623ef510b9a3b4d/1605050158827/NIVA-+Policy+and+Fact+Sheet+11-9-20+%282%29.pdf. (Accessed November 9 2020).

Packer, Jan, and Julie Ballantyne. 2011. “The Impact of Music Festival Attendance on Young People’s Psychological and Social Well-Being.” Psychology of Music 39(2):164–181.

Peisner, David. 2020. “Concerts Aren’t Back. Livestreams Are Ubiquitous. Can They Do the Job?” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/21/arts/music/concerts-livestreams.html. (Accessed July 21 2020).

Perreault, Olivia. 2020. “Coachella Postponement Brings $700M Hit To Local Economy.” TicketNews. https://www.ticketnews.com/2020/04/coachella-postponement-local-economy. (Accessed April 13 2020).

Peters, Bill. 2020. “How The Live-Music Apocalypse May Save Streaming — From Itself.” Investors Business Daily. https://www.investors.com/news/music-industry-faces-transformaton-artists-fight-spotify-coronavirus-closes-concert-venues/. (Accessed November 12 2020).

Pittman, Sarah. 2019. “I Did It My Way: Indie Promoters Survey.” Pollstar. https://www.pollstar.com/article/i-did-it-my-way-indie-promoters-survey-138494. (Accessed July 25 2019).

Pollstar. 2020. “Pollstar Projects 2020 Total Box Office Would Have Hit $12.2 Billion.” Pollstar. https://www.pollstar.com/article/pollstar-projects-2020-total-box-office-would-have-hit-122-billion-144197. (Accessed April 3 2020).

Promoters. 2019. “Pollstar Worldwide Ticket Sales.” Pollstar. https://www.pollstar.com/Chart/2019/12/2019WorldwideTicketSalesTop100Promoters_796.pdf. (Accessed December 16 2019).

Reference for Business. 2019. https://www.referenceforbusiness.com/history2/54/Live-Nation-Inc.html. (Accessed December 2 2019).

Rendon, Francisco. 2020. “Paradigm Lays Off Furloughed Employees.” Pollstar. https://www.pollstar.com/article/paradigm-lays-off-furloughed-employees-146472. (Accessed September 17 2020).

Resnikoff, Paul. 2011. “Live Nation: 90% of a Ticket Price Goes to Artist Fees….” Digital Music News. https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2011/06/28/ticketprice/. (Accessed June 28 2011).

RIAA. 2020. “Music Covid Relief.” https://musiccovidrelief.com/. (accessed December 16 2020).

Robinson, Dave, and Karl Spracklen. 2019. “Music, Beer and Performativity in New Local Leisure Spaces: Case study of a Yorkshire Dales Market Town.” International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure 2(4):329–346.

Rogers, Ian. 2010. “‘You’ve Got to Go to Gigs to Get Gigs’: Indie Musicians, Eclecticism and the Brisbane Scene.” Continuum. Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 22(5):639–649.

Rössler, Mechtild. 2008. “Applying Authenticity to Cultural Landscapes.” APT Bulletin 39(2/3):47–52.

Rys, Dan. 2020. “US Recorded Music Revenue Reaches $11.1 Billion in 2019, 79% From Streaming: RIAA.” Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/8551881/riaa-music-industry-2019-revenue-streaming-vinyl-digital-physical/. (Accessed February 25 2020).

Shusterman, Richard. 1999. “Moving Truth: Affect and Authenticity in Country Musicals.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 57(2):221–233.

Sisario, Ben. 2016. “Live Nation Adds Governors Ball to Its Music Festival Lineup.” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/11/business/media/live-nation-adds-governors-ball-to-its-music-festival-lineup.html. (Accessed April 11 2016).

Sisario, Ben. 2020. “He Helped Create Lollapalooza. Now he Wants to Save Live Music.” New York Times. (Accessed October 28 2020).

Smith, Dylan. 2020. “Lupe Fiasco Will Require Proof of a COVID-19 Vaccine to Attend His Shows.” Digital Music News. https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2020/12/07/lupe-fiasco-vaccine-requirement/. (Accessed December 7 2020).

SOS. 2020. “Save Our Stages Act.” https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/4258. (Accessed 20 December 2020).

Stanton, Aleen L., and John Schofield. 2021. “Reimagining Nashville: The Changing Place of Country.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice:1–19.

Statista. 2021a. “Live Nation Entertainment’s Revenue from 2006 to 2019.” Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/193700/revenue-of-live-nation-entertainment-since-2006/#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20live%20event%20specialist,dollars%20was%20generated%20through%20concerts. (Accessed January 8 2021).

Statista. 2021b. “Leading Music Promoters Worldwide 2019, by Number of Tickets Sold.” Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/304982/leading-music-promoters-worldwide/. (Accessed January 11 2021).

Stein, Germano. 2010. “Declining Sales are Reducing the Incentive to Create Music? A Messy Debate.” Streaming Machinery. https://streamingmachinery.com/2010/07/26/declining-sales-are-reducing-the-incentive-to-create-music-a-messy-debate/. (Accessed July 26 2010).

Tschmuck, Peter. 2020. “The Music Industry in the COVID-19 Pandemic – Live Nation.” Music Business Research. https://musicbusinessresearch.wordpress.com/2020/12/16/the-live-music-industry-in-the-covid-19-pandemic-live-nation/ (accessed December 16 2020).

Webster, Emma. 2011. “Promoting Live Music in the UK: A Behind-the-Scenes Ethnography. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Glasgow.

Willman, Chris. 2021. “Bandsintown Introduces ‘Plus’ Subscription Service for Streaming Concerts From Indie Acts.” Variety Media. https://variety.com/2021/music/news/bandsintown-plus-streaming-subscription-indie-bands-1234883431/. (Accessed January 12 2021).

Willman, Chris, and Jem Aswd. 2021. “Music Predictions for 2021: Adele and Rihanna Will Be Back… But Summertime Festivals Probably Won’t.” Variety Media. https://variety.com/2021/music/news/music-predictions-2021-festivals-adele-rihanna-taylor-swift234877989/?fbclid=IwAR18yMEc0TbdfiwMOAj0UJOhuLAVbBTC3tytXEN9SKWn2M8Zm6ckyv0ekMc. (Accessed January 3 2021).

Wynn, Jonathan R. 2015. Music/City: American Festivals and Placemaking in Austin, Nashville, and Newport. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zagorski-Thomas, Simon. 2010. “The Stadium in your Bedroom: Functional Staging, Authenticity and the Audience-led Aesthetic in Record Production.” Popular Music 29(2):251–266.